by Bruce Wells | Jun 2, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

June 2, 1908 – Goose Creek Oilfield discovered –

Drilled on Galveston Bay wetlands, the first offshore well in Texas revealed a giant oilfield 20 miles southeast of Houston, according to the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). Inspired by reports of bubbles on the surface where Goose Creek emptied into the bay, the Houston-based syndicate Goose Creek Production Company made the discovery at a depth of 1,600 feet.

A single well of the Goose Creek field in 1917 produced 35,000 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 3,050 feet. Circa 1919 photo by Frank Schlueter courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“Within days the syndicate sold out to a subsidiary of the Texas Company, the future Texaco,” notes TSHA, adding the Goose Creek field, “spurred exploration for deep-seated (salt) domes, and led to the discovery of some of the largest oilfields in the United States.”

In 1909, Howard Hughes Sr. secretly tested an experimental dual-cone rock bit at Goose Creek. Humble Oil and Refining Company constructed a refinery adjacent to the field In 1921, naming the site Baytown.

June 3, 1979 – Bay of Campeche Oil Spill

Drilling in about 150 feet of water, the semi-submersible platform Sedco 135 suffered a blowout 50 miles off Mexico’s Gulf Coast. The Pemex well Ixtoc 1 spilled 3.4 million barrels of oil before being controlled nine months later. Considering the spill’s size, the environmental impact proved less than expected, according to a 1981 report by the Coordinated Program of Ecological Studies in the Bay of Campeche. Surveys of Campeche Sound conducted in 1980 reported, “Evaporation, dispersion, photo-oxidation and biodegradation processes played a major role in attenuating the harmful environmental effects of the oil spill.”

June 4, 1872 – Pennsylvania Oilfields bring Petroleum Jelly

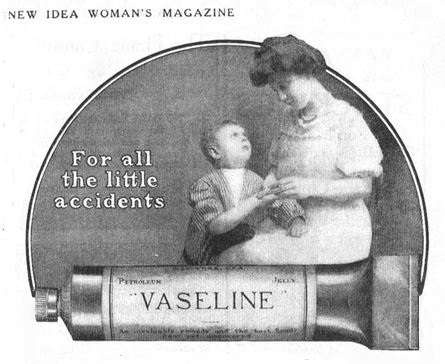

A young chemist living in New York City, Robert Chesebrough, patented “a new and useful product from petroleum,” which he named “Vaseline.” His patent proclaimed the virtues of this purified extract of petroleum distillation residue as a lubricant, hair treatment, and balm for chapped hands.

patented “a new and useful product from petroleum,” which he named “Vaseline.” His patent proclaimed the virtues of this purified extract of petroleum distillation residue as a lubricant, hair treatment, and balm for chapped hands.

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96 years old. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

When the 22-year-old chemist visited the new Pennsylvania oilfields in 1865, he noted drilling was often confounded by a paraffin-like substance that clogged the wellhead. Drillers used the “rod wax” as a quick first aid for abrasions.

Chesebrough returned to New York City and worked in his laboratory to purify the well byproduct, which he first called “petroleum jelly.” Female customers would discover that mixing lamp black with Vaseline made an impromptu mascara. In 1913, Mabel Williams employed just such a concoction and it led to the founding of a cosmetic company.

Learn more in The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.

June 4, 1892 – Devastation of Pennsylvania Oil Regions

After weeks of thunderstorms in Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek Valley, the Spartansburg Dam on Oil Creek burst, sending torrents of water that killed more than 100 people and destroyed homes and businesses in Titusville and Oil City. The disaster was compounded when fires broke out.

Titusville, Pennsylvania, residents used the “Colonel Drake Steam Pumper” during the great flood and fire of 1892. Photo by John Mather courtesy Drake Well Museum and Park.

“This city during the past twenty-four hours has been visited by one of the most appalling fires and overwhelming floods in the history of this country,” reported the New York Times from Oil City. Oilfield photographer John A. Mather documented the devastation, which included his Titusville studio and 16,000 glass-plate negatives.

Learn more in Oilfield photographer John Mather.

June 4, 1896 – Henry Ford drives his “Quadricycle”

Driving the first car he ever built, Henry Ford left a workshop behind his home on Bagley Avenue in Detroit, Michigan. He had designed his “Quadricycle” in his spare time while working as an engineer for Edison Illuminating Company. Ford chose the name because his handmade, 500-pound “horseless carriage” ran on four bicycle tires. Inspired by advancements in gasoline-fueled engines, he founded the Henry Ford Company in 1903.

June 4, 1921 – Petroleum Seismograph tested

A team of earth scientists tested an experimental seismograph device on a farm three miles north of Oklahoma City and determined it could accurately map subsurface structures. Led by Prof. John C. Karcher and W.P. Haseman, the team from the University of Oklahoma found that seismology could be useful for oil and natural gas exploration and production. Further seismic reflection tests, including one in the Arbuckle formation in August, confirmed their results.

June 6, 1932 – First Federal Gasoline Tax

The federal government taxed gasoline for the first time when the Revenue Act of 1932 added a one-cent per gallon excise tax to U.S. gasoline sales. The first state to tax gasoline was Oregon, which imposed a one-cent per gallon tax in 1919. Colorado, New Mexico, and other states followed. The federal tax, last raised on October 1, 1993, has remained at 18.4 cents per gallon (24.4 cents per gallon for diesel). About 60 percent of federal gasoline taxes are used for highway and bridge construction.

June 6, 1944 – English Channel Pipelines fuel WWII Victory

As the D-Day invasion began along 50 miles of fortified French coastline in Normandy, logistics for supplying the effort would include two top-secret engineering feats — the construction of artificial harbors followed by the laying of pipelines across the English Channel.

Operation PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) unspooled flexible steel pipelines across the English Channel, but the channel was deep, the French ports distant.

Code-named “Mulberrys” and using a design similar to modern jack-up offshore rigs, the artificial harbors used barges with retractable pylons to provide platforms to support floating causeways extending to the beaches.

To fuel the Allied advance into Nazi Germany, Operation PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) used flexible steel pipelines wound onto giant “conundrums” designed to spool off when towed. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower later acknowledged the vital importance of the oil pipelines.

Learn more in PLUTO, Secret Pipelines of WW II.

June 6, 1976 – Oil Billionaire J. Paul Getty dies

With a fortune reaching $6 billion (about $32 billion in 2023), J. Paul Getty died at 83 at his estate near London. Born into his father’s petroleum wealth from the Oil Company of Tulsa, Getty made his first million by age 23 from buying and selling oil leases.

The J. Paul Getty Museum art collection is housed in the Getty Center (above) and the Getty Villa on the California Malibu coast.

“I started in September 1914, to buy leases in the so-called red-beds area of Oklahoma,” Getty once told the New York Times. “The surface was red dirt and it was considered impossible there was any oil there. My father and I did not agree and we got many leases for very little money which later turned out to be rich leases.”

Getty, who incorporated Getty Oil in 1942, gave more than $660 million from his estate to the J. Paul Getty Museum.

______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It

(2008); The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Around Titusville, Pennsylvania, Images of America

(2010); Around Titusville, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2004); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford

(2004); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford (2014); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Code Name MULBERRY: The Planning Building and Operation of the Normandy Harbours

(2014); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Code Name MULBERRY: The Planning Building and Operation of the Normandy Harbours (1977); The Great Getty (1986). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1977); The Great Getty (1986). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | May 27, 2025 | Petroleum Products

How oilfield paraffin created Vaseline and Maybelline cosmetics.

Few associate 1860s oil wells with women’s eyes, but they are fashionably related. From paraffin to Vaseline, this is the story of how the goop that accumulated around the sucker rods of America’s earliest oil wells made its way to eyelashes.

In 1865, a 22-year-old Robert Chesebrough left the prolific oilfields of Pithole and Titusville, Pennsylvania, to return to his Brooklyn, New York, laboratory. He carried samples of a waxy substance that clogged wellheads. He already had dabbled in the “coal oil” business with experiments on refinery processes.

Robert Chesebrough will find a way to purify the waxy paraffin-like substance that clogged oil wells in early Pennsylvania petroleum fields. Photo courtesy Unilever Corp.

Chesebrough’s laboratory expertise included distilling cannel coal into kerosene (coal oil), a lamp fuel in high demand among consumers. He also knew of the process for refining crude oil into a better kerosene.

Thus, when Edwin L. Drake completed the first U.S. oil well in August 1859, Chesebrough was among those who rushed to Pennsylvania oilfields to make his fortune.

“Now commenced a scene of excitement beyond description,” reported Scientific American. “The Drake well was immediately thronged with visitors arriving from the surrounding country, and within two or three weeks thousands began to pour in from the neighboring States.”

Chesebrough was convinced he too could get rich from the “black gold” of Pennsylvania’s oilfields.

Oilfield Sucker Rod Wax

Amid the Venango County exploration and production chaos, the young chemist noted a waxy buildup often confounded drilling. This paraffin-like substance clogged the wellhead and drew curses from riggers who had to stop drilling to scrape it away.

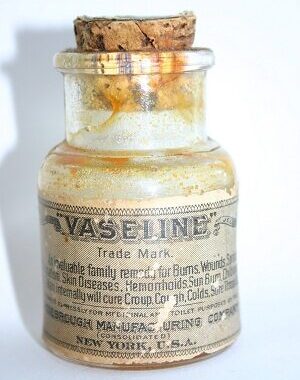

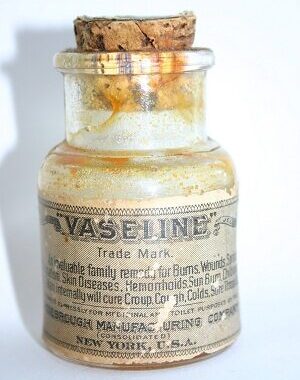

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96. This early bottle is from the collection of the Drake Well Museum in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

The only virtue of this goopy oilfield “sucker rod wax” was as an immediately available first aid for the abrasions, burns, and other wounds routinely afflicting the crews.

Paraffin to Vaseline

Chesebrough abandoned his notion of drilling a gusher and returned to New York, where he worked in his laboratory to purify the troublesome sucker-rod wax, which he dubbed “petroleum jelly,” one of America’s earliest petroleum products.

By August 1865, Chesebrough had filed the first of several patents “for purifying petroleum or coal oils by filtration.”

The chemist experimented with the analgesic effects of his extract by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying the purified petroleum jelly. He also gave it to Brooklyn construction workers to treat their minor scratches and abrasions.

After refining oilfield wax, Chesebrough experimented by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying his petroleum balm.

On June 4, 1872, Chesebrough patented a new product – “Vaseline.” His paraffin to Vaseline patent extolled the balm’s virtues as a leather treatment, lubricator, pomade, and balm for chapped hands. Chesebrough soon had a dozen wagons distributing the product around New York.

Customers used the “wonder jelly” creatively: treating cuts and bruises, removing stains from furniture, polishing wood surfaces, restoring leather, and preventing rust. Within 10 years, Americans were buying it at the rate of a jar a minute

Women had once used toothpicks to mix lamp black with Vaseline. By 1917, Tom Williams was selling premixed “Lash-Brow-Ine” by mail order. Photo courtesy Sharrie Williams.

An 1886 issue of Manufacture and Builder even reported, “French bakers are making large use of vaseline in cake and other pastry. Its advantage over lard or butter lies in the fact that, however stale the pastry may be, it will not become rancid.”

Flavor notwithstanding, Chesebrough himself consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day. He lived to be 96 years old. It was not long before thrifty young ladies found another use for Vaseline.

Mabel’s Eyelashes

As early as 1834, the popular book Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion suggested alternatives to the practice of darkening eyelashes with elderberry juice or a mixture of frankincense, resin, and mastic.

“By holding a saucer over the flame of a lamp or candle, enough ‘lamp black’ can be collected for applying to the lashes with a camel-hair brush,” the book advised.

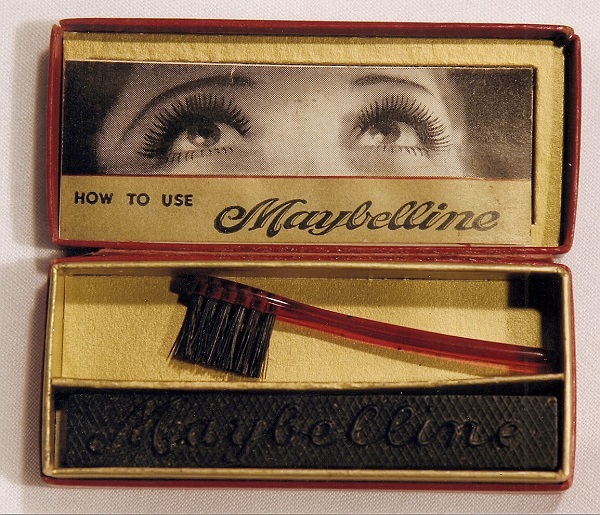

Chesebrough’s female customers found that mixing lamp black with Vaseline using a toothpick made an impromptu mascara. Some sources claim that Miss Mabel Williams in 1913 employed just such a concoction preparing for a date. Williams was dating Chet Hewes.

Women were using Vaseline to make mascara by 1915. Cosmetic industry giant Maybelline traces its roots to the petroleum product. “What a Difference Maybelline Does Make” magazine ad from 1937.

Perhaps using coal dust or some other readily available darkening agent, she applied the mixture to her eyelashes for a date. Her brother, Thomas Lyle Williams, was intrigued by her method and decided to add Vaseline in the mixture, noted a Maybelline company historian.

Lash-Brow-Ine

A more reliable version of the story — told by Williams’ grandniece Sharrie Williams — has Mabel demonstrating “a secret of the harem” for her brother.

“In 1915, when a kitchen stove fire singed his sister Mabel’s lashes and brows, Tom Lyle Williams watched in fascination as she performed what she called ‘a secret of the harem’ mixing petroleum jelly with coal dust and ash from a burnt cork and applying it to her lashes and brows,” Sharrie Williams explained in her 2007 book, The Maybelline Story and the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It.

“Mabel’s simple beauty trick ignited Tom’s imagination and he started what would become a billion-dollar business,” concluded Williams.

Silent screen stars like Theda Bara, right, helped glamorize Maybelline mascara. By the 1930s, the paraffin to Vaseline to mascara concoction was available at five-and-dime stores for 10 cents a cake.

Inspired by his sister’s example, he began selling the mixture by catalog, calling it “Lash-Brow-Ine” (an apparent concession to the mascara’s Vaseline content). Women loved it.

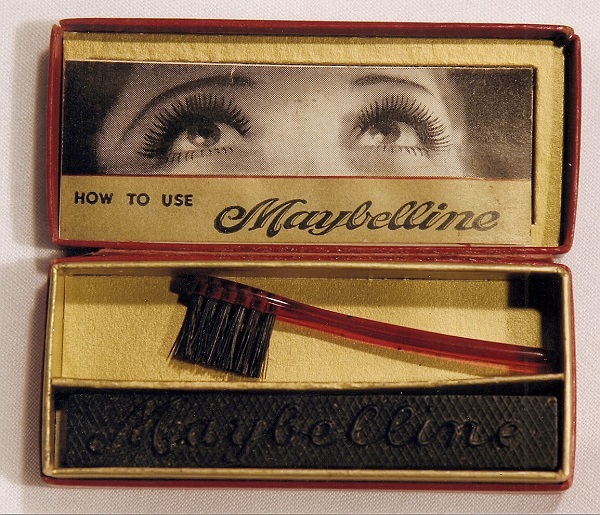

When it became clear that Lash-Brow-Ine had potential, Williams, doing business in Chicago as Maybell Laboratories, on April 24, 1917, trademarked the name as a “preparation for stimulating the growth of eyebrows and eyelashes.”

Mail-Order Mascara

With sales exceeding $100,000 by 1920, Williams decided to rename the mascara Maybelline in honor of his sister, who worked with him in the Chicago office. Maybell Laboratories was renamed Maybelline in 1923 and concentrated on eye makeup. Mabel married Chet Hewes in 1926.

An unlikely petroleum product for women’s eyes.

Whatever its petroleum product beginnings, Hollywood helped expand the Williams family cosmetics empire. The 1920s silent screen had brought new definitions to glamour. Theda Bara – an anagram for “Arab Death” – and Pola Negri, each with daring eye makeup, smoldered in packed theaters across the country.

Maybelline trumpeted its mail-order mascara in movie and confession magazines as well as Sunday newspaper supplements. Sales continued to climb. By the 1930s, Maybelline mascara was available at the local five-and-dime store for 10 cents a cake.

Both Vaseline, now part of Unilever, and Maybelline, later a subsidiary of L’Oréal, have continued as highly successful products, distantly removed from northwestern Pennsylvania’s “Wonder Jelly” introduced in 1870.

Special thanks to Linda Hughes, granddaughter of Mabel and Chet Hewes, who reviewed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s paraffin to Vaseline to Mascara article. She asked AOGHS to note that Mabel was very dedicated to her brother’s work –- and helped run the Maybelline company in Chicago.

Crayola Crayons

Paraffin from early U.S. oilfields also proved key to the phenomenal success of business partners Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith, who in 1891 patented an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.”

Soon, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed carbon black with oilfield paraffin to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker able to “stay on all” and named “Staonal,” still sold today. The company also manufactured a popular “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and a red, iron oxide barn paint.

By 1903, the Binney & Smith Company added color to paraffin for a new product, “Crayola” crayons. Learn more about their petroleum products in Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons. Oilfield paraffin also found its way into novelty candies like “wax lips.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/vaseline-maybelline-history. Last Updated: June 1, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2005.

patented “a new and useful product from petroleum,” which he named “Vaseline.” His patent proclaimed the virtues of this purified extract of petroleum distillation residue as a lubricant, hair treatment, and balm for chapped hands.

(2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2008); The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It

(2010); Around Titusville, Pennsylvania, Images of America

(2004); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford

(2014); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Code Name MULBERRY: The Planning Building and Operation of the Normandy Harbours

(1977); The Great Getty (1986). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.