by Bruce Wells | Feb 1, 2024 | Energy Education Resources

Growing oil demand challenged petroleum geologists, who organized a professional association.

As demand for petroleum grew during World War I, the science for finding oil and natural gas reserves remained obscure when a small group of geologists in 1917 organized what became the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

AAPG began as the Southwestern Association of Petroleum Geologists in Tulsa, Oklahoma, after about 90 geologists gathered at Henry Kendall College, now Tulsa University. They formed an association of earth scientists on February 10, 1917, “to which only reputable and recognized petroleum geologists are admitted.”

AAPG members maintain a professional business code.

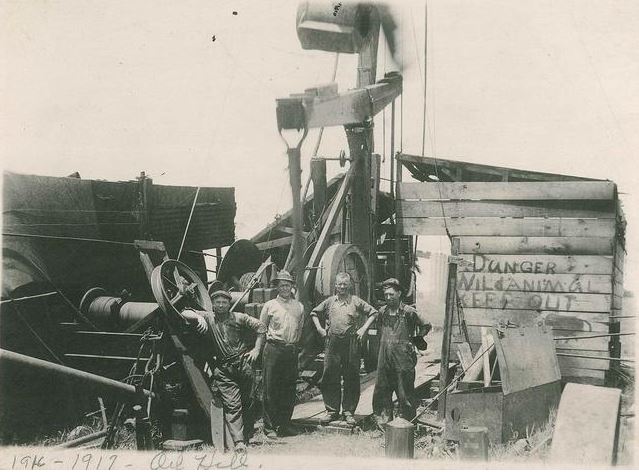

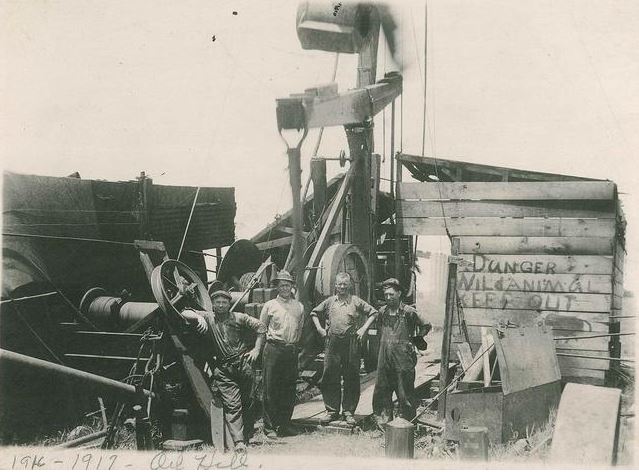

Rapidly multiplying mechanized technologies of the “Great War” brought desperation to finding and producing vast supplies of oil. America entered the First War I two months after AAPG’s founding. An October 1917 giant oilfield discovery at Ranger, Texas, inspired a British War Cabinet member to declare, “The Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Rock Hounds

In January 1918, the AAPG convention of in Oklahoma City reported 167 active members and 17 associate members. After adopting its present name one year after organizing at Henry Kendall College, the group issued its first technical bulletin, using papers and presentations delivered at the 1917 Tulsa meeting.

The professional “rock hounds” produced a mission statement that included promoting the science of geology, especially relating to oil and natural gas. The geologists also committed to encouraging “technology improvements in the methods of exploring for and exploiting these substances.”

AAPG was founded in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at Henry Kendall College — today’s Tulsa University.

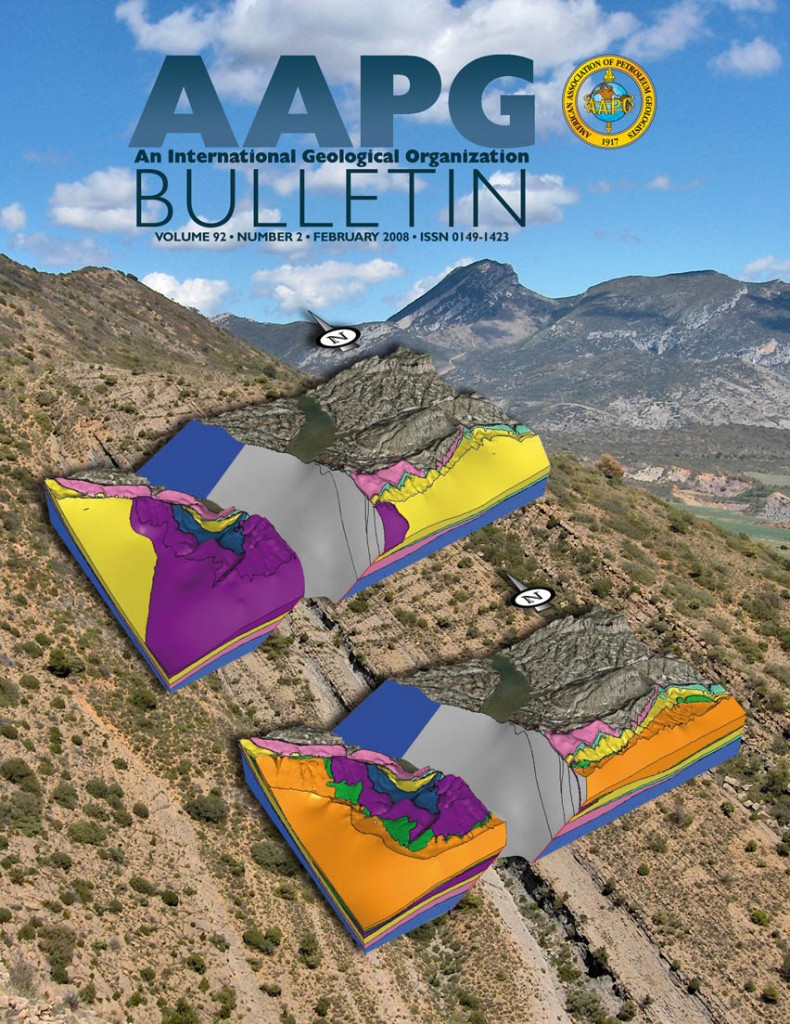

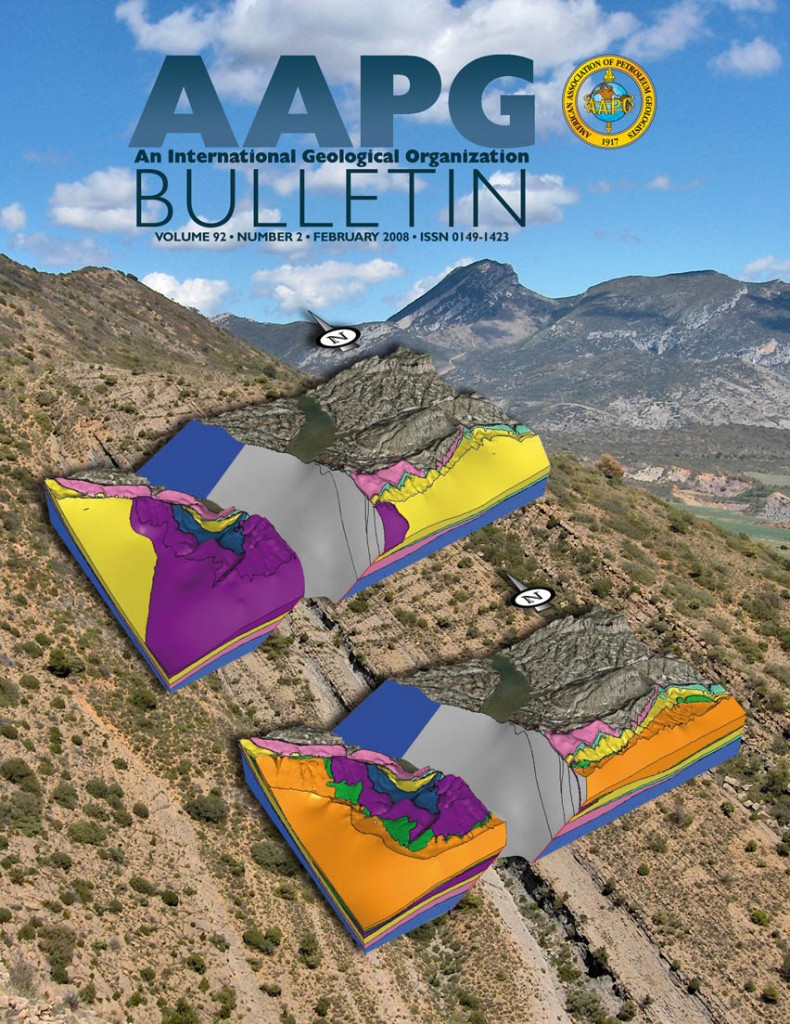

AAPG also began publishing a bimonthly journal that remains among the most respected in the industry. The peer-reviewed Bulletin included papers written by leading geologists of the day.

With a subscription price of five dollars, the journal was distributed to members, university libraries, and other industry professionals.

Finding Faults and Anticlines

By 1920, one petroleum trade magazine — after complaining of the industry’s lack of skilled geologists — noted the “Association Grows in Membership and Influence; Combats the Fakers.”

The article praised AAPG professionalism and warned of “the large number of unscrupulous and inadequately prepared men who are attempting to do geological work.”

Similarly, the Oil Trade Journal praised AAPG for its commitment “to censor the great mass of inadequately prepared and sometimes unscrupulous reports on geological problems, which are wholly misleading to the industry.”

Perhaps the best known such fabrication is related to the men behind the 1930 East Texas oilfield discovery — a report entitled “Geological, Topographical And Petroliferous Survey, Portion of Rusk County, Texas, Made for C.M. Joiner by A.D. Lloyd, Geologist And Petroleum Engineer.”

Using very scientific terminology, A.D. Lloyd’s document described Rusk County geology — its anticlines, faults, and a salt dome — all features associated with substantial oil deposits…and all completely fictitious.

The fabrications nevertheless attracted investors, allowing Joiner and “Doc” Lloyd to drill a well that uncovered a massive oil field, still the largest conventional oil reservoir in the lower-48 states.

AAPG’s peer-reviewed journal first appeared in 1918, one year after the association’s first meeting in Tulsa.

Equally imaginative science came from Lloyd’s earlier descriptions of the “Yegua and Cook Mountain” formations and the thousands of seismographic registrations he ostensibly recorded. Lloyd, a former patent medicine salesman, and other self-proclaimed geologists, were the antithesis of the AAPG professional ethic.

In 1945, AAPG formed a “Committee on Boy Scout Literature” to assist the Boy Scouts of America in updating requirements for the “mining” badge, which had been awarded since 1911 (learn more in Merit Badge for Geology).

By 1953, AAPG membership had grown to more than 10,000 and a permanent headquarters building opened Tulsa. The association’s 2022 membership included about 40,000 members in 129 countries in the upstream energy industry, “who collaborate — and compete — to provide the means for humankind to thrive.”

The world’s largest professional geological society, a nonprofit organization, maintains a membership code to assure “integrity, business ethics, personal honor, and professional conduct.”

Oil Patch Historians

Longtime AAPG member Ray Sorenson, a Tulsa-based consulting geologist, has made numerous presentations about the history of petroleum. After publishing papers in leading academic journals, he adapted many of his contributions for the association’s 2007 Discovery Series, “First Impressions: Petroleum Geology at the Dawn of the North American Oil Industry.”

Further, Sorenson continued to research and collect a vast amount of material documenting the earliest signs of oil — worldwide references to hydrocarbons earlier that the 1859 first U.S. oil well drilled by Edwin Drake in Pennsylvania.

Drake expert and geologist and historian William Brice, professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, in 2009 published Myth, Legend, Reality – Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry. His 661-page epic was researched and written as part of the U.S. petroleum industry’s 150th anniversary (learn more in Edwin Drake and his Oil Well),

As part if AAPG’s 2017 centennial events, geologist Robbie Rice Gries published Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology 1917-2017. Researched with help from AAPG volunteers, her 405-page book includes contributors’ personal stories, written correspondence, and photographs dating back to the early 1900s.

The stories in Gries’ book should be read by every petroleum geologist, geophysicist and petroleum engineer, according to independent producer Marlan Downey, founder of Roxanna Oil Company. “Partly for the pleasure of the sprightly told adventures, partly for a sense of history, and, significantly, because it engenders a proper respect towards all women professionals, forging their unique way in a ‘man’s world.’”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology 1917-2017 (2017); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Myth, Legend, Reality – Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “AAPG – Geology Pros since 1917.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/energy-education-resources/aapg-geology-pros-since-1917. Last Updated: February 1, 2024. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2023 | Petroleum Pioneers

Giant Mid-Continent oilfield revealed in 1915 by emerging science of petroleum geology.

Community leaders in El Dorado, Kansas, were desperate for their town to live up to its name, especially after big natural gas discoveries at nearby Augusta and at Paola, south of Kansas City. It would be oil, not natural gas, that would do just that when a 1915 well revealed a giant oilfield east of Wichita. In 1918, the El Dorado field would produce almost 29 million barrels of oil.

One-hundred years after the historic discovery, the Butler County Times-Gazette told the prolific oilfield’s “black gold” story.

“In 1915, about 3,000 people called the rural agricultural community of El Dorado home,” the newspaper reported. “They had no idea events toward the end of that year would begin something that would forever change not just El Dorado, but the state and an entire industry.”

Petroleum Geologists

The science of petroleum geology played a key role in discovering the El Dorado oilfield — and many other Mid-Continent fields that followed. Drilled by Wichita Natural Gas, a subsidiary of Cities Service Company, beginning in late September 1915, the October 5 exploratory well revealed a 34-square-mile oilfield.

A marker erected in 1940 at the Stapleton No. 1 well commemorates the October 5, 1915, discovery of the El Dorado, Kansas, oilfield. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Stapleton No. 1 well produced 95 barrels a day from 600 feet before being deepened to 2,500 feet to produce 110 barrels of oil a day from the Wilcox sands. Discoveries one year earlier in nearby Augusta had prompted El Dorado city fathers to seek a geological study of the area, according to Larry Skelton of the Kansas Geological Survey.

“Pioneers named El Dorado, Kansas, in 1857 for the beauty of the site and the promise of future riches but not until 58 years later was black rather than mythical yellow gold discovered when the Stapleton No. 1 oil well came in on October 5, 1915,” explained Lawrence Skelton in a 1997 USGS Journal article.

By 1914 interest was growing in Butler county and south central Kansas. “A few positive finds had been made, but nothing exciting,” Skelton noted in “Striking It Big in Kansas” for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

“Henry Doherty, founder of Cities Service in 1910, was seeking new gas reserves and opted for scientific exploration in lieu of wildcatting,” he wrote in the 2002 AAPG Explorer article.

After the 1915 El Dorado oilfield discovery, few companies would drill a well without first seeking the advice of a geologist, Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

Doherty hired geologists Charles Gould and Everett Carpenter in Oklahoma, sending them to Augusta, in Butler County. Gould had organized the Oklahoma Geological Survey in 1908 and served as its first director until 1911. According to Skelton, the geologists mapped prominent anticlinal structures in Permian Age limestone.

Finding Oil at Anticlines

By late 1914, several Augusta exploratory wells found commercial volumes of natural gas. Several wells also found oil. These developments “chafed El Dorado city fathers.”

According to geologist Skelton, about 15 miles northeast of Augusta, El Dorado had unsuccessfully searched for hydrocarbons since the 1890s. City leaders decided to hire Erasmus Haworth, the state geologist and chairman of the University of Kansas geology department.

“He mapped a large anticline on the same formations used by Gould and Carpenter at Augusta and selected a site that proved to be a dry hole,” Skelton explained.

Undeterred, Cities Service subsidiary Wichita Natural Gas bought the town’s 790 leased acres for $800, verified Haworth’s work and began drilling in late September 1915. The Stapleton No. 1 well found oil within a week.

“Using scientific geological survey methodology for the first time, Cities Service had identified a promising anticline,” Skelton noted. “His field work outlined the El Dorado Anticline.”

Butler County’s geologic revelations encouraged Gulf Oil, Standard Oil, and other companies to acquire leases around Augusta and El Dorado. In addition to Henry Doherty, industry leaders like Archibald Derby, John Vickers and William Skelly established successful El Dorado oil-producing and refining companies.

As Butler County wells multiplied, Oil Hill became the largest “company towns” in the world with some 8,500 residents. Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

“So the idea from that point forward, no oil company in the world would go and drill a well without seeking the advice of a geologist first,” proclaimed the executive director of the Kansas Oil Museum.

“Before 1915, geologists were seen in the same vein as witching and doodlebugs. They were just charlatans,” explained Warren Martin in a 2015 Butler County Times-Gazette article on the centennial of Stapleton No. 1 well.

“It fundamentally transformed it from that point going forward,” Martin added. “Geology was established as one of the great science industries.”

Also see Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology.

Kansas Oil and Gas Boom

With the influx of thousands of workers, even Wichita accommodations were overwhelmed. Butler County’s population, about 23,000 in 1910, nearly doubled in 1920. To house its workers, Empire Gas & Fuel Company (formerly Wichita Natural Gas) built a 64-acre town northwest of El Dorado.

When the United States entered World War I, oil production escalated with the El Dorado field producing almost 29 million barrels of oil in 1918 — about nine percent of the nation’s oil.

The Kansas Oil Museum includes drilling and production equipment. The museum annually hosts a “Rockfest celebration of geology and oil and gas culture.” Photo by Bruce Wells

Although Oil Hill and its more than 8,000 residents, swimming pool, tennis courts and small golf course would disappear by the late 1950s, at the time it was called the largest “company town” in the world.

The Stapleton No. 1 well, which produced oil until 1967, can be visited by tourists — as can El Dorado’s Kansas Oil Museum, which includes 20 acres of rig displays, equipment exhibits and models of the region’s refinery history. The museum hosts events in an Energy Education Center, offers a variety of K-12 programs, and annually celebrates a “Rockfest” for aspiring geologists.

The Kansas museum’s pumping unit exhibits, the largest one on the grounds, educates visitors about evolving production technologies. It includes a 1970s pumpjack donated by Hawkins Oil Company. Visitors explore a variety of buildings depicting a typical petroleum boom town like Oil Hill.

The state’s earliest oil production began in 1892 at Neodesha in eastern Kansas — the first Kansas oil well — later proclaimed the first commercial discovery west of the Mississippi River.

A natural gas well along the Oklahoma border at Caney, ignited in 1906 and took five weeks to bring under control (see Kansas Gas Well Fire). In far western Kansas, the Hugoton Natural Gas Museum preserves the history of a multistate natural gas geologic formation.

_______________________________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Kansas Oil Boom.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/kansas-oil-boom. Last Updated: September 29, 2023. Original Published Date: October 4, 2015.

(2009); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.