by Bruce Wells | Jun 5, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Oilfield production technologies began in Pennsylvania with an economical way to pump multiple wells.

In the earliest days of the petroleum industry, which began with an 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, production technologies used steam power and a walking beam pump system that evolved into ways for economically producing oil from multiple wells.

Just as drilling technologies evolved from spring poles to steam-powered cable tools to modern rotary rigs, oilfield production also improved.

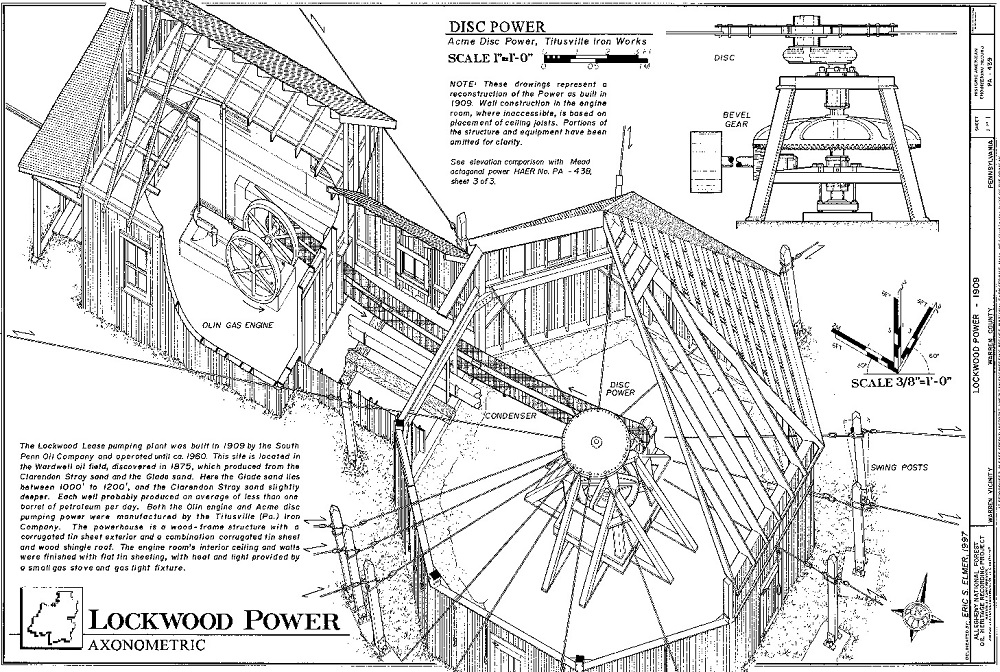

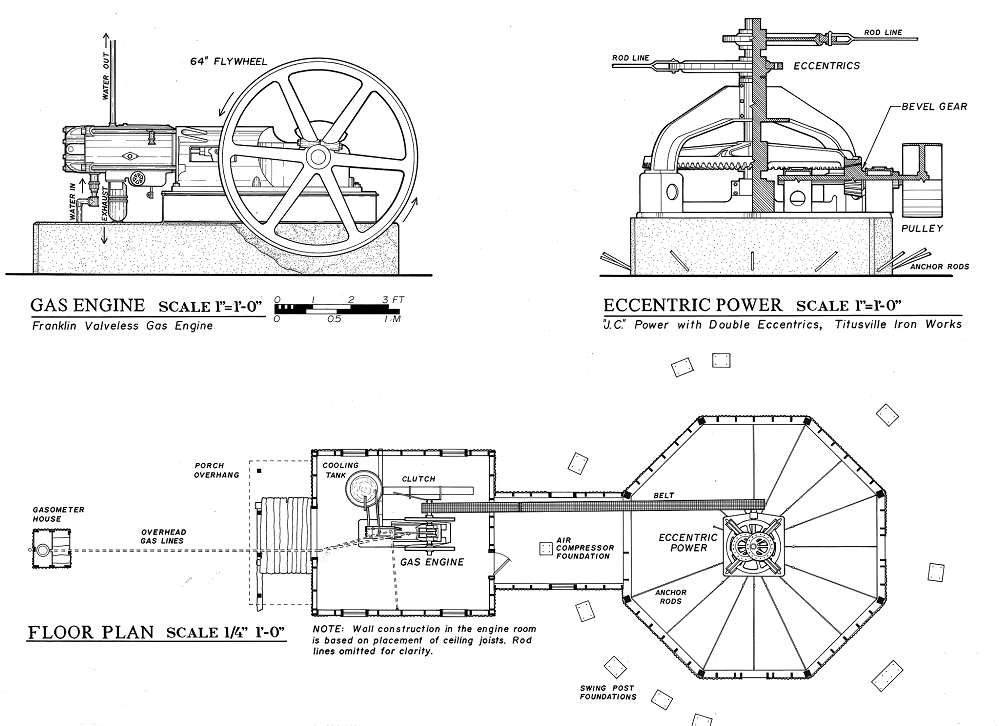

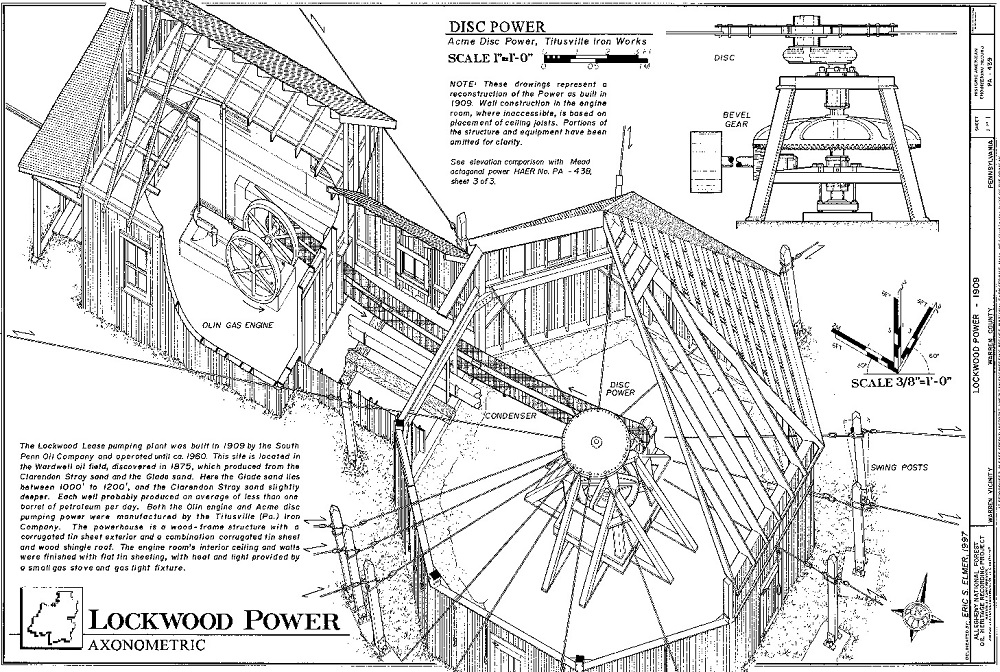

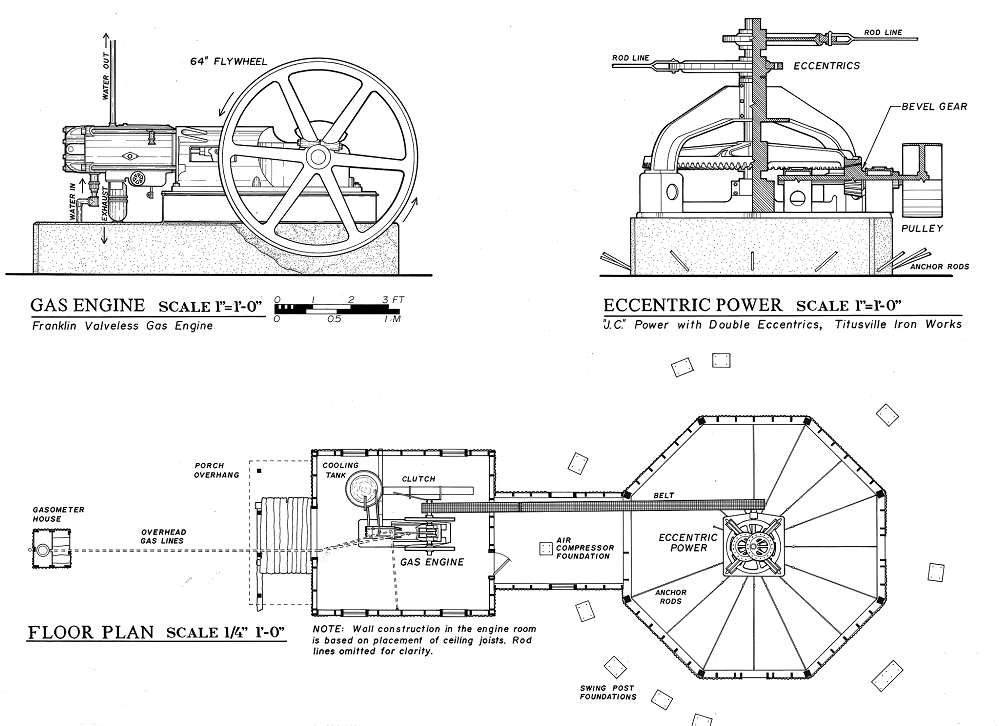

This image of a circa 1909 double eccentric power wheel manufactured by the Titusville (Pennsylvania) Iron Works is just one example of what can be discovered online at public domain resources. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Collections.

In the early days of the industry, oil production technology used steam power and a wooden walking beam. A steam engine at each well raised and lowered one end of the beam. An oil production technique perfected in Pennsylvania used central power for pumping low-production wells to economically recover oil.

Eccentric Wheels

A Library of Congress (LOC) photograph from 1909 shows a “double eccentric power wheel,” part of an innovative centralized power system. The oilfield technology from a South Penn Oil Company (the future Pennzoil) lease between the towns of Warren and Bradford, Pennsylvania.

The LOC photograph preserves the oilfield technology that used the two wheels’ elliptical rotation for simultaneously pumping multiple oil wells. The wheels’ elliptical rotation simultaneously pumped eleven remote wells. This central pump unit operated in the Morris Run oilfield, discovered in 1883. It was manufactured at the Titusville Iron Works.

Many oilfield history resources can be found in the Library of Congress Digital Collections and the related images of petroleum history photography. The development of centralized pumping systems — eccentric wheels and jerk lines — often are preserved in high-resolution files.

The Morris Run field in Pennsylvania produced oil from two shallow “pay sands,” both at depths of less than 1,400 feet. It was part of a series of other early important discoveries.

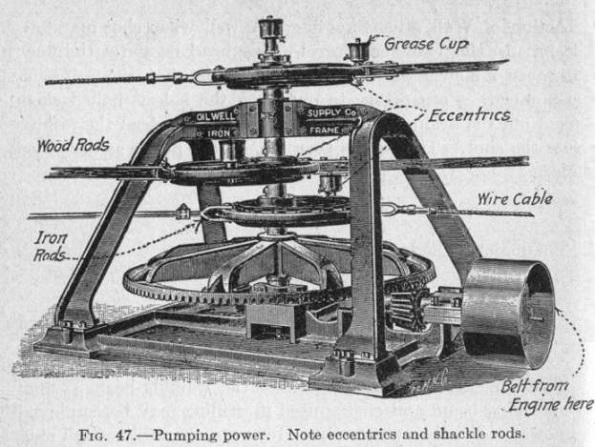

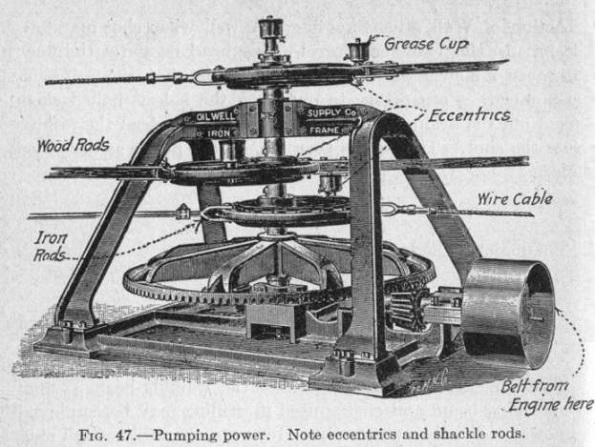

Late 18th-century Oil Well Supply Company illustration of pumping system using rods, cables, and an eccentric wheel.

In 1881, the Bradford field alone accounted for 83 percent of all the oil produced in the United States (see Mrs. Alford’s Nitro Factory). In 2004, new technologies began producing natural gas from a far deeper formation, the Marcellus Shale.

Oil production from some of the earliest shallow Pennsylvania wells declined to only about half a barrel of oil a day, but some continued pumping into 1960. On the West Coast, a 1913 central pumping unit produced from California’s largest oilfield three decades longer.

Midway-Sunset Jack Plant

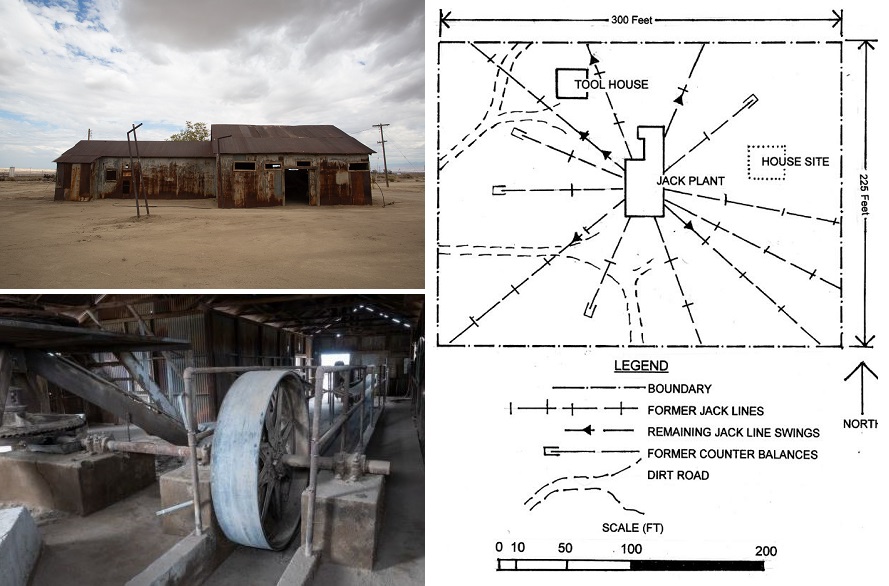

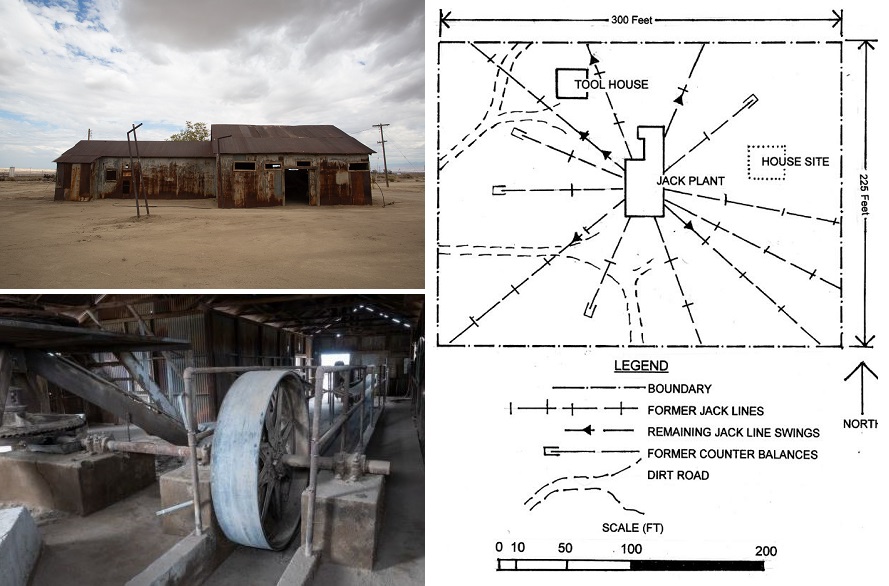

On June 9, 2023, the National Park Service added the Midway-Sunset Jack Plant to the National Register of Historic Places — thanks to Mark Smith, who submitted the application to preserve the facility. Installed by the Engineers Oil Company in 1913, the Kern County jack plant pumped oil until 1990.

In operation until 1990, California’s Midway-Sunset Jack Plant used eccentric-wheel technologies from the late 19th century. The Kern County plant pumped more than 1.5 million barrels of oil. Photos courtesy John Harte. Illustration courtesy San Joaquin Geological Society.

“The Midway-Sunset Jack Plant is an extremely rare example of central power and ‘jack-line’ oil pumping technology on its original site and housed in its original building,” Smith noted in his 45-page draft application to the State Historical Resources Commission. “Its design and operational history reflect significant advancements in oil extraction technology.”

According to company records, the jack plant’s slowly rotating eccentric wheels produced 1.5 million barrels of oil during its lifetime. The end came when the bearing of the vertical shaft became worn, causing the shaft to wobble. The wobble of the eccentric gears made the pumping of the wells out of balance.

Pumping Multiple Wells

As the number of oil wells grew in the early days of America’s petroleum industry in Pennsylvania, simple water-well pumping technologies began to be replaced with steam-driven walking-beam pumping systems.

At first, each well had an engine house where a steam engine raised and lowered one end of a sturdy wooden beam, which pivoted on the cable-tool well’s “Samson Post.” The walking beam’s other end cranked a long string of sucker rods up and down to pump oil to the surface.

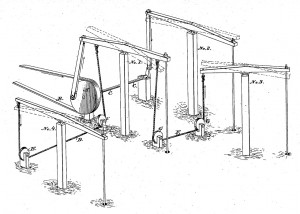

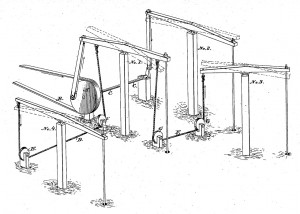

America’s oilfield technologies advanced in 1875 with this “Improvement In Means For Pumping Wells” invented in Pennsylvania.

Recognizing that pumping multiple wells with a single steam engine would boost efficiency, on April 20, 1875, Albert Nickerson and Levi Streeter of Venango County, Pennsylvania, patented their “Improvement in Means for Pumping Wells.”

Their system was the forerunner of wooden or iron rod jerk line systems for centrally powered oil production. This technology, eventually replaced by counter-balanced pumping units, will operate well into the 20th century – and remain an icon of early oilfield production.

“By an examination of the drawing it will be seen that the walking beam to well No. 1 is lifting or raising fluid from the well. Well No. 3 is also lifting, while at the same time wells 2 and 4 are moving in an opposite direction, or plunging, and vice versa,” the inventors explained in their patent application (No. 162,406).

Central Power Units

“Heretofore it has been necessary to have a separate engine for each well, although often several such engines are supplied with steam from the same boiler,” noted Nickerson and Streeter.

“The object of our invention is to enable the pumping of two or more wells with one engine…By it the walking beams of the different wells are made to move in different directions at the same time, thereby counterbalancing each other, and equalizing the strain upon the engine.”

An Allegheny National Forest Oil Heritage Series illustration of an oilfield “jack plant” in McKean County, Pennsylvania.

Steam initially drove many of these central power units, but others were converted to burn natural gas or casing-head gas at the wellhead – often using single-cylinder horizontal engines. Examples of the engines, popularly called “one lungers” by oilfield workers, have been collected and restored (see Coolspring Power Museum).

Many widely used techniques of drilling and pumping oil were developed to recover the high-quality “Pennsylvania Grade” oil. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

The heavy and powerful engine — started by kicking down on one of the iron spokes — transferred power to rotate an eccentric wheel, which alternately pushed and pulled on a system of rods linked to pump jacks at distant oil wells.

Pump Jacks

“Transmitting power hundreds of yards, over and around obstacles, etc., to numerous pump jacks required an ingenious system of reciprocating rods or cables called Central Power and jerker lines,” explains documentation from an Allegheny National Forest Oil Heritage Series.

The series documentation includes an early illustration of an oilfield “jack plant” in McKean County, Pennsylvania. The long rod lines were also called shackle lines or jack lines.

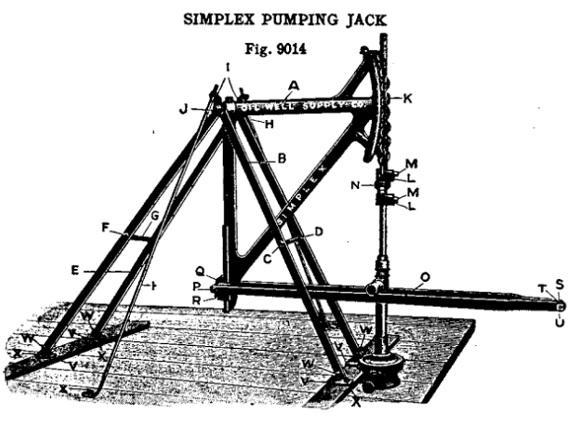

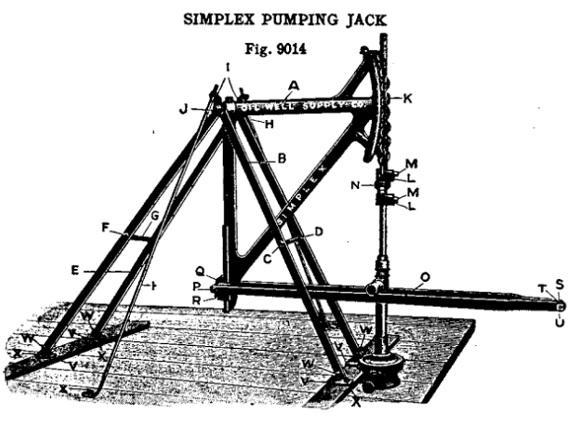

A single engine with eccentric wheel connecting rod lines could economically pump oil using Oil Well Supply Company’s “Simplex Pumping Jacks.”

Around 1913, with electricity not readily available, the Simplex Pumping Jack became a popular offering from Oil Well Supply Company of Oil City, Pennsylvania. The simple and effective technology could often be found at the very end of long jerk lines.

A central power unit could connect and run several of these dispersed Simplex pumps. Those equipped with a double eccentric wheel could power twice as many.

Roger Riddle, a retired field guide for the West Virginia Oil & Gas Museum in Parkersburg, grew up around central power units and recalls the rhythmic clanking of rod lines.

Riddle guided visitors through dense nearby woods where remnants of the elaborate systems rust. The heavy equipment once “pumped with just these steel rods, just dangling through the woods,” he said. “You could hear them banging along – it was really something to see those work. The cost of pumping wells was pretty cheap.”

The heyday of central power units passed when electrification arrived, nonetheless, a few such systems remain in use today. Learn more about the evolution of petroleum production methods, the first counter-balanced “Nodding Donkeys” in All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology.

______________________

Recommended Reading: Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language (2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Eccentric Wheels and Jerk Lines.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/jerk-lines-eccentric-wheels. Last Updated: June 15, 2025. Original Published Date: November 20, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 2, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

June 2, 1908 – Goose Creek Oilfield discovered –

Drilled on Galveston Bay wetlands, the first offshore well in Texas revealed a giant oilfield 20 miles southeast of Houston, according to the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). Inspired by reports of bubbles on the surface where Goose Creek emptied into the bay, the Houston-based syndicate Goose Creek Production Company made the discovery at a depth of 1,600 feet.

A single well of the Goose Creek field in 1917 produced 35,000 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 3,050 feet. Circa 1919 photo by Frank Schlueter courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“Within days the syndicate sold out to a subsidiary of the Texas Company, the future Texaco,” notes TSHA, adding the Goose Creek field, “spurred exploration for deep-seated (salt) domes, and led to the discovery of some of the largest oilfields in the United States.”

In 1909, Howard Hughes Sr. secretly tested an experimental dual-cone rock bit at Goose Creek. Humble Oil and Refining Company constructed a refinery adjacent to the field In 1921, naming the site Baytown.

June 3, 1979 – Bay of Campeche Oil Spill

Drilling in about 150 feet of water, the semi-submersible platform Sedco 135 suffered a blowout 50 miles off Mexico’s Gulf Coast. The Pemex well Ixtoc 1 spilled 3.4 million barrels of oil before being controlled nine months later. Considering the spill’s size, the environmental impact proved less than expected, according to a 1981 report by the Coordinated Program of Ecological Studies in the Bay of Campeche. Surveys of Campeche Sound conducted in 1980 reported, “Evaporation, dispersion, photo-oxidation and biodegradation processes played a major role in attenuating the harmful environmental effects of the oil spill.”

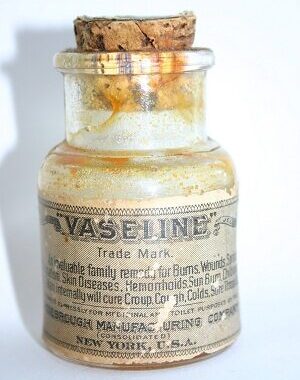

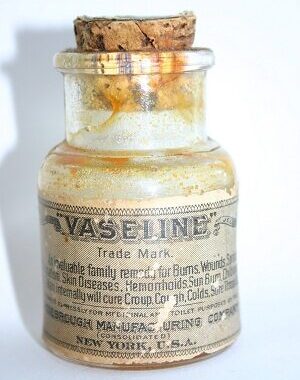

June 4, 1872 – Pennsylvania Oilfields bring Petroleum Jelly

A young chemist living in New York City, Robert Chesebrough, patented “a new and useful product from petroleum,” which he named “Vaseline.” His patent proclaimed the virtues of this purified extract of petroleum distillation residue as a lubricant, hair treatment, and balm for chapped hands.

patented “a new and useful product from petroleum,” which he named “Vaseline.” His patent proclaimed the virtues of this purified extract of petroleum distillation residue as a lubricant, hair treatment, and balm for chapped hands.

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96 years old. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

When the 22-year-old chemist visited the new Pennsylvania oilfields in 1865, he noted drilling was often confounded by a paraffin-like substance that clogged the wellhead. Drillers used the “rod wax” as a quick first aid for abrasions.

Chesebrough returned to New York City and worked in his laboratory to purify the well byproduct, which he first called “petroleum jelly.” Female customers would discover that mixing lamp black with Vaseline made an impromptu mascara. In 1913, Mabel Williams employed just such a concoction and it led to the founding of a cosmetic company.

Learn more in The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.

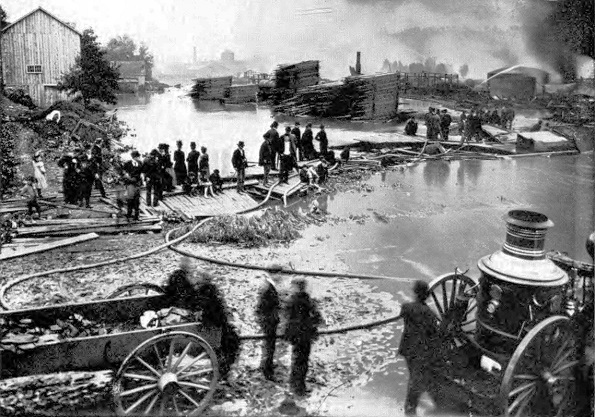

June 4, 1892 – Devastation of Pennsylvania Oil Regions

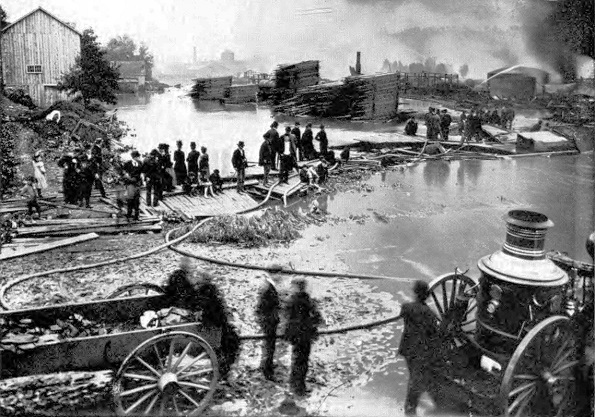

After weeks of thunderstorms in Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek Valley, the Spartansburg Dam on Oil Creek burst, sending torrents of water that killed more than 100 people and destroyed homes and businesses in Titusville and Oil City. The disaster was compounded when fires broke out.

Titusville, Pennsylvania, residents used the “Colonel Drake Steam Pumper” during the great flood and fire of 1892. Photo by John Mather courtesy Drake Well Museum and Park.

“This city during the past twenty-four hours has been visited by one of the most appalling fires and overwhelming floods in the history of this country,” reported the New York Times from Oil City. Oilfield photographer John A. Mather documented the devastation, which included his Titusville studio and 16,000 glass-plate negatives.

Learn more in Oilfield photographer John Mather.

June 4, 1896 – Henry Ford drives his “Quadricycle”

Driving the first car he ever built, Henry Ford left a workshop behind his home on Bagley Avenue in Detroit, Michigan. He had designed his “Quadricycle” in his spare time while working as an engineer for Edison Illuminating Company. Ford chose the name because his handmade, 500-pound “horseless carriage” ran on four bicycle tires. Inspired by advancements in gasoline-fueled engines, he founded the Henry Ford Company in 1903.

June 4, 1921 – Petroleum Seismograph tested

A team of earth scientists tested an experimental seismograph device on a farm three miles north of Oklahoma City and determined it could accurately map subsurface structures. Led by Prof. John C. Karcher and W.P. Haseman, the team from the University of Oklahoma found that seismology could be useful for oil and natural gas exploration and production. Further seismic reflection tests, including one in the Arbuckle formation in August, confirmed their results.

June 6, 1932 – First Federal Gasoline Tax

The federal government taxed gasoline for the first time when the Revenue Act of 1932 added a one-cent per gallon excise tax to U.S. gasoline sales. The first state to tax gasoline was Oregon, which imposed a one-cent per gallon tax in 1919. Colorado, New Mexico, and other states followed. The federal tax, last raised on October 1, 1993, has remained at 18.4 cents per gallon (24.4 cents per gallon for diesel). About 60 percent of federal gasoline taxes are used for highway and bridge construction.

June 6, 1944 – English Channel Pipelines fuel WWII Victory

As the D-Day invasion began along 50 miles of fortified French coastline in Normandy, logistics for supplying the effort would include two top-secret engineering feats — the construction of artificial harbors followed by the laying of pipelines across the English Channel.

Operation PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) unspooled flexible steel pipelines across the English Channel, but the channel was deep, the French ports distant.

Code-named “Mulberrys” and using a design similar to modern jack-up offshore rigs, the artificial harbors used barges with retractable pylons to provide platforms to support floating causeways extending to the beaches.

To fuel the Allied advance into Nazi Germany, Operation PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) used flexible steel pipelines wound onto giant “conundrums” designed to spool off when towed. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower later acknowledged the vital importance of the oil pipelines.

Learn more in PLUTO, Secret Pipelines of WW II.

June 6, 1976 – Oil Billionaire J. Paul Getty dies

With a fortune reaching $6 billion (about $32 billion in 2023), J. Paul Getty died at 83 at his estate near London. Born into his father’s petroleum wealth from the Oil Company of Tulsa, Getty made his first million by age 23 from buying and selling oil leases.

The J. Paul Getty Museum art collection is housed in the Getty Center (above) and the Getty Villa on the California Malibu coast.

“I started in September 1914, to buy leases in the so-called red-beds area of Oklahoma,” Getty once told the New York Times. “The surface was red dirt and it was considered impossible there was any oil there. My father and I did not agree and we got many leases for very little money which later turned out to be rich leases.”

Getty, who incorporated Getty Oil in 1942, gave more than $660 million from his estate to the J. Paul Getty Museum.

______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It

(2008); The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Around Titusville, Pennsylvania, Images of America

(2010); Around Titusville, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2004); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford

(2004); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford (2014); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Code Name MULBERRY: The Planning Building and Operation of the Normandy Harbours

(2014); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Code Name MULBERRY: The Planning Building and Operation of the Normandy Harbours (1977); The Great Getty (1986). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1977); The Great Getty (1986). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | May 30, 2025 | Petroleum Art

Thousands of glass-negative images document the earliest scenes of America’s petroleum industry.

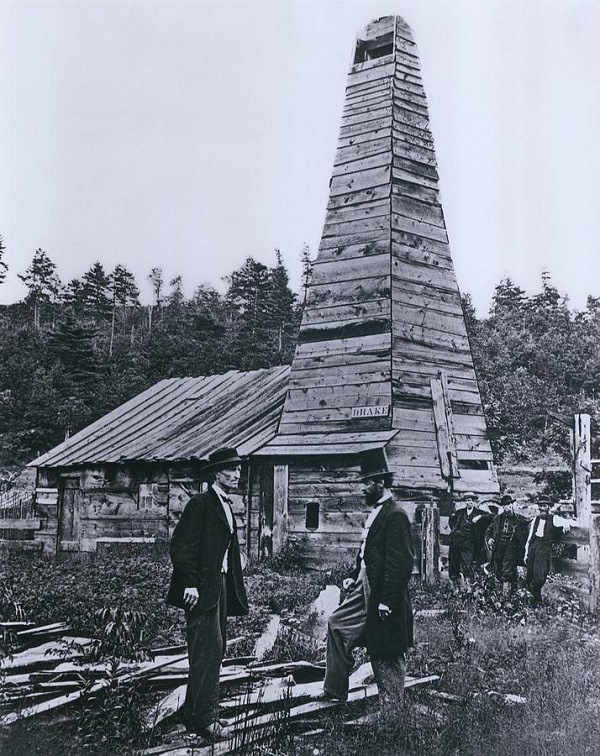

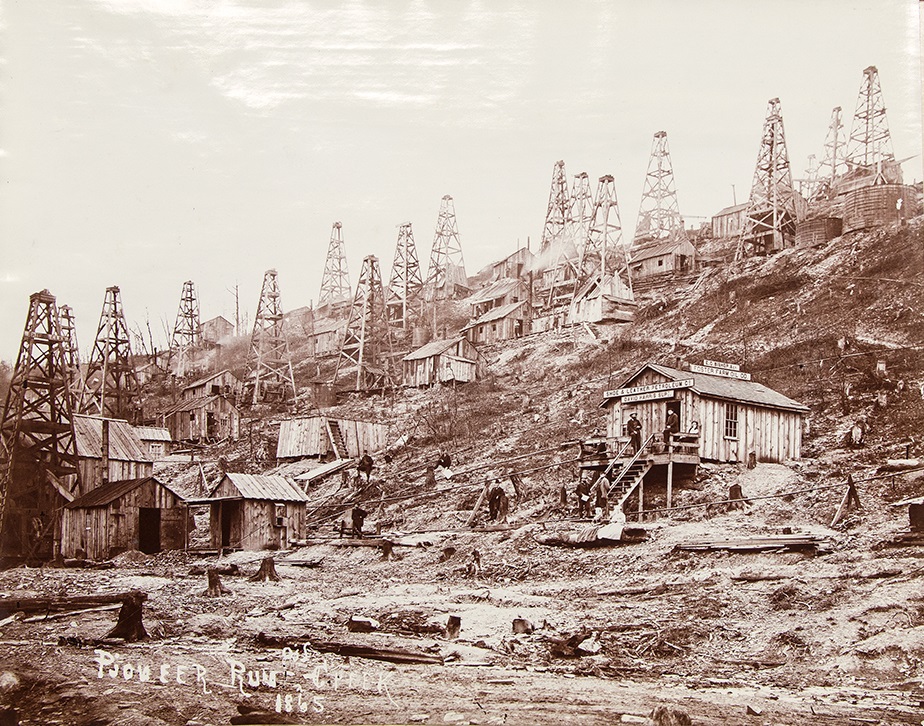

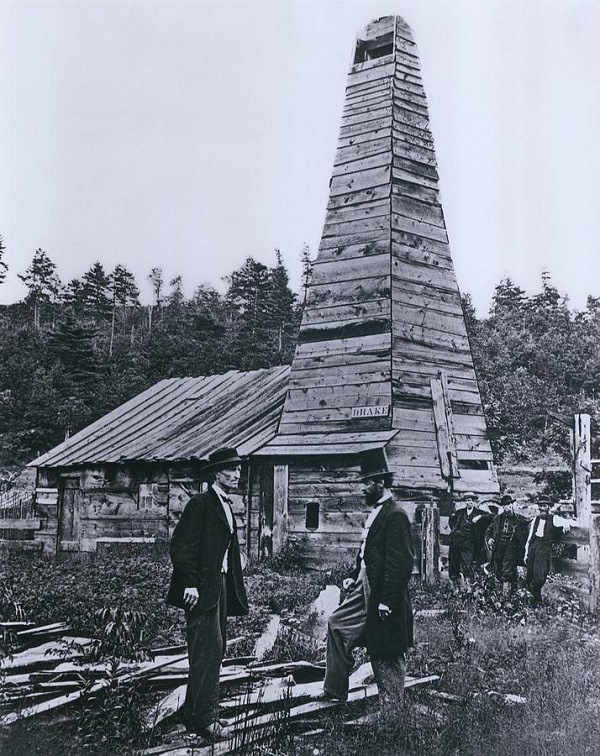

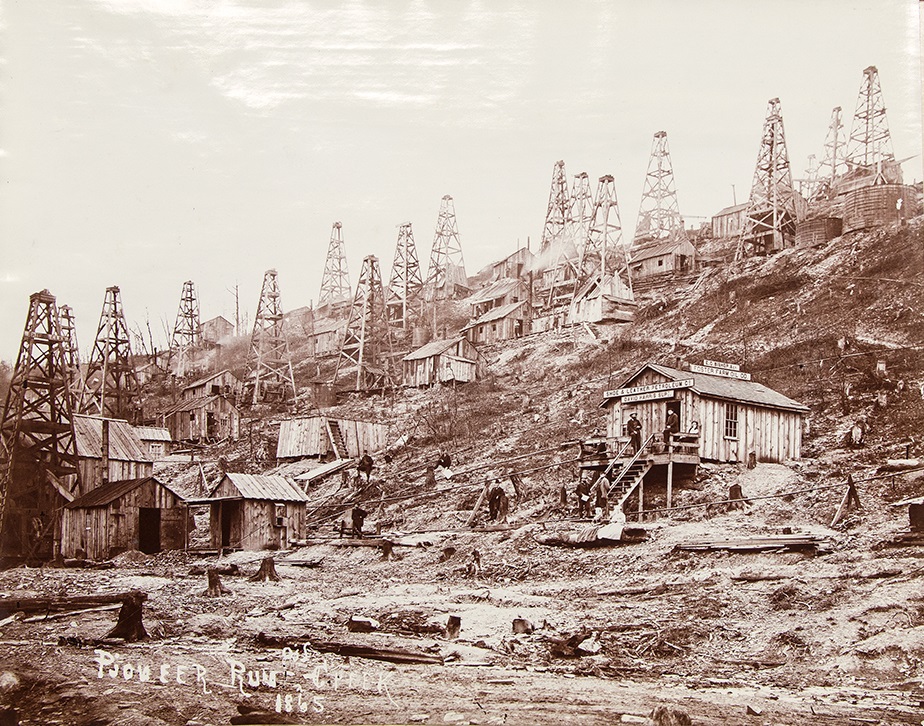

Soon after the first American oil well in 1859 launched the U.S. petroleum industry in remote northwestern Pennsylvania, an English emigrant began documenting life in the oilfields.

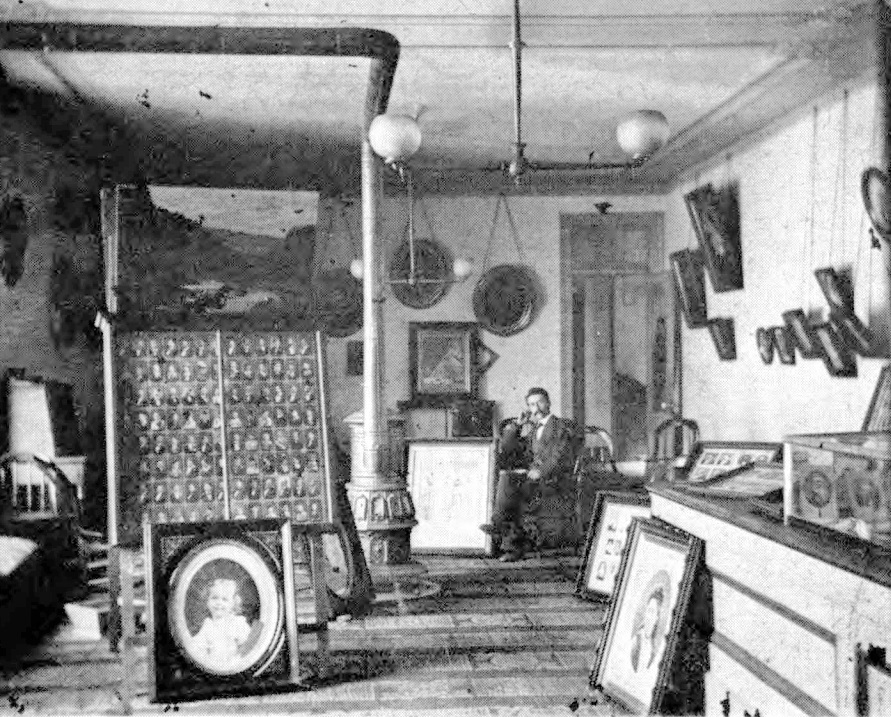

John A. Mather (1829-1915) photographed the people, places and technology from the earliest days of oil exploration. In the fall of 1860, he set up his first studio in Titusville, Pennsylvania — where he would begin to amass more than 20,000 glass-plate negatives.

Oil Creek Artist

Titusville and nearby Oil City and Franklin, in the heart of the growing Pennsylvania oil regions (soon joined by the boom town of Pithole), proved ideal locations for documenting the people, events and evolving drilling technologies of petroleum exploration and production.

Iconic but often misidentified 1866 photo by John A. Mather features Edwin L. Drake (in top hat) with friend Peter Wilson standing at the rebuilt derrick and engine house of the 1859 first U.S. commercial oil well. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum and Park.

What Civil War photographers Matthew Brady and James Gardner documented on battlefields, Mather accomplished in Pennsylvania’s oilfields. In 1866, Titusville’s “Oil Creek Artist” photographed the now iconic image of Edwin L. Drake, standing at the original drilling site (rebuilt after the first oil well fire).

Like Brady, Mather abandoned making one-of-kind daguerreotypes and ambrotypes in favor of wet plate negatives using collodion — a flammable, syrupy mixture also called “nitrocellulose.” With one glass plate, many paper copies of an image could be printed and sold.

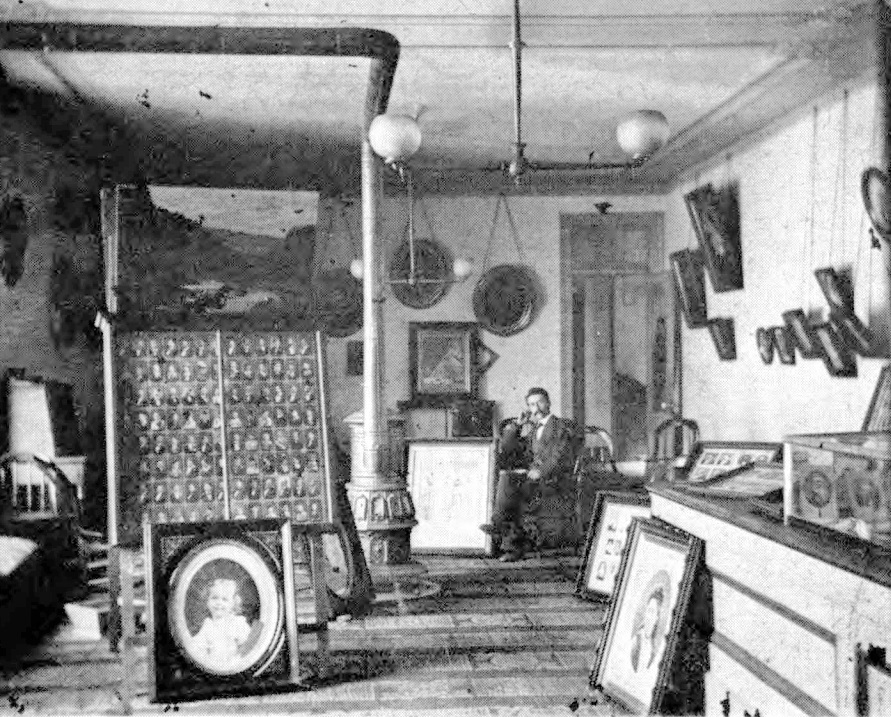

Oilfield photographer John Aked Mather, probably a self-portrait circa 1900.

However, unlike most of the era’s studio photographers, Mather transported his camera and chemicals into the industrial chaos of early Pennsylvania oilfields. But like most people in the new oil region, Mather was susceptible to “oil fever;” he hoped to drill some successful wells himself.

Oil Fever

Above all, the oil regions continued to boom. The gamble of drilling for new oilfield discoveries brought excitement. As “oil fever” spread, polka and waltz song sheets like the Petroleum Court Dance became popular.

Having narrowly missed the opportunity for a one-sixteenth share of the Sherman Well, which proved to be the “best single strike of the year,” Mather and three associates invested in oil wells near booming Pithole Creek. He proved to be better at using a camera.

John Mather photographs courtesy Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine and Drake Well Museum, Titusville. Above, the interior of his Titusville studio, circa 1865.

Mather’s investment in finding oil at Pithole Creek did not lead to producing any commercial quantities. He tried again on the Holmden Farm off West Pithole Creek. His unsuccessful drilling effort proved to be one of the last wells in the infamous boom town Pithole.

Many tried, but few in the increasingly crowded oil regions would rival the wealth of the celebrated “Coal Oil Johnny.” Years later, Mather acknowledged that the excitement of the drilling for “black gold” was so great that he “forsook photography for the oil business.”

Meanwhile, the young U.S. petroleum industry learned some hard lessons. Highly pressurized wells and disasters like the 1861 fatal Rouseville oil well fire brought attention to a new science, petroleum geology.

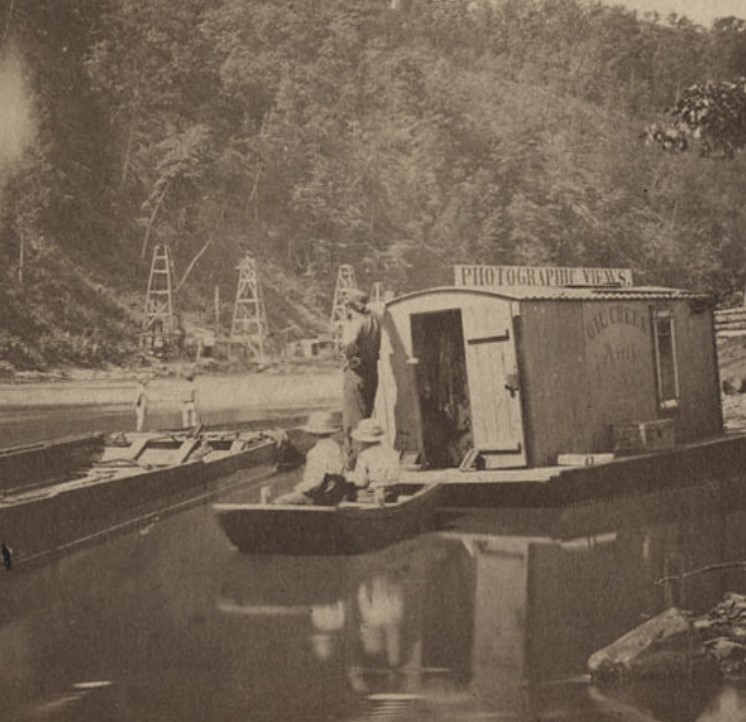

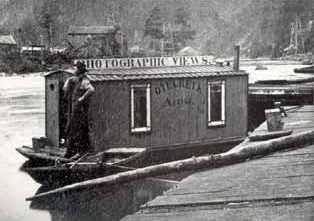

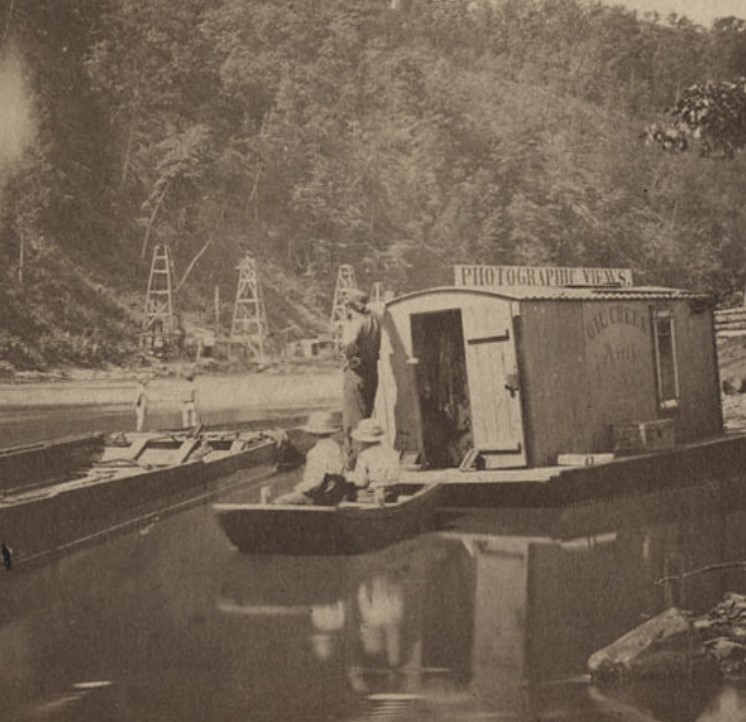

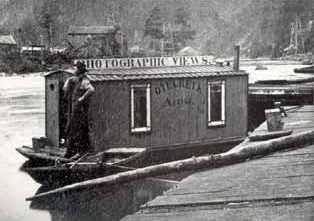

Detail from the 19th-century stereoview “Oil Regions of Pennsylvania,” published by C. W. Woodward of Rochester, N.Y., featuring John Mather’s floating studio and dark room.

Returning to the oilfields with his camera, Mather’s rolling darkroom and floating studio traveled up and down Oil Creek. In 2008, photographic historian John Craig (1943-2011) noted the discovery of a Mather image in a stereoview card published by C.W. Woodward.

“We have had the card for years and assumed that the boat belonged to Woodward,” the historian noted. “When I made the scan I noticed that the side of the boat carried a sign ‘Oil Creek Artist.’ I Googled and found that the studio/darkroom boat belonged to John A. Mather.”

At its peak, Mather’s collection amounted to more than 16,000 glass negatives. The trade magazine Petroleum Age described his oilfield photography as “so perfect in finish it stands the test of time.”

Oil Creek Flood and Fire

On Sunday morning June 5, 1892, and after weeks of rain, Oil Creek’s overflowing Spartansburg Dam failed at about 2:30 a.m. A wall of water and debris swelled towards Titusville and its oil works, seven miles downstream.

“On rushed the mad waters, tearing away bridge after bridge, carrying away horses, homes and people,” one newspaper reported about the flood’s devastation. Then fire erupted from ruptured benzine and oil storage tanks.

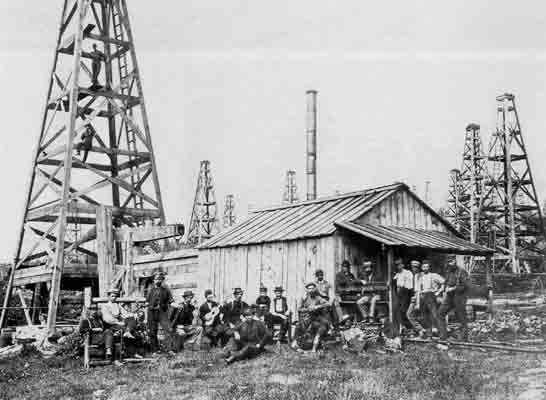

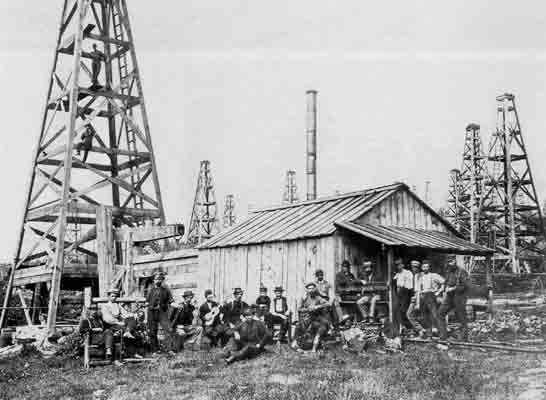

Oilfield workers pose on and among their oil derricks and engine houses in this 1864 John Mather photo from the Drake Well Museum collection in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Newspapers all over America carried stories of the disaster. In Montana, the Helena Independent headlines included: “Waters of an Overflowing Creek Become a Rushing Mass of Flames” and victims being, “Spared by the Deluge Only to Become the Prey of the Fire.”

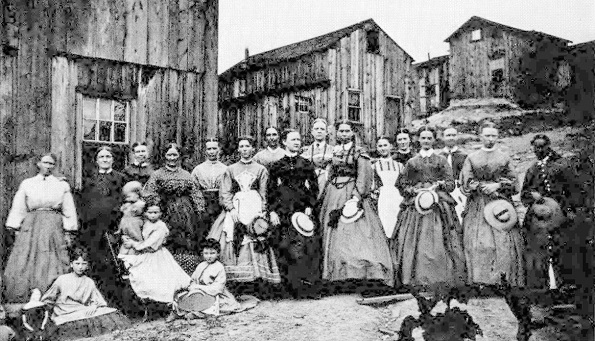

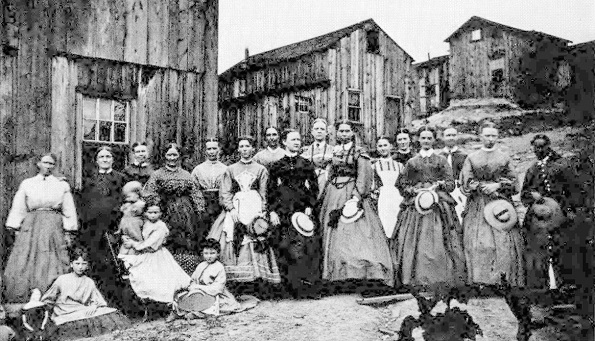

John Mather’s photographs documented family life in remote early oil boom towns. He also briefly caught “oil fever” and unsuccessfully invested in a few wells in the booming Pithole Creek field.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle added: “The Waters Subside and The Flames Die Away, Revealing the Full Extent of the Calamity.” Oil City and Titusville were “Nearly Wiped From Off the Earth.”

Unfortunately, Mather’s studio flooded to a depth of five feet, destroying expensive equipment — and most of his life’s work of prints from glass plate negatives.

Pennsylvania oil towns were “Nearly Wiped From Off the Earth” by an 1892 fire and flood that destroyed thousands of Mather’s prints and glass plates. Photo from Drake Well Museum collection.

As the fires and flood continued, Mather set up his camera and photographed the disaster in progress with his bulky equipment, which already was being rendered obsolete by new imaging technologies.

Photography Legacy

Just a few years before the Titusville flood, George Eastman of Rochester, New York, introduced celluloid roll film and created an entirely new market: amateur snapshot photography.

Expertise in preparing fragile glass plates and dangerous chemicals was no longer required. Instead, Kodak offered, “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest.”

The “Oil Creek Artist” visited potential customers using his floating darkroom.

As oil booms moved to discoveries in other states, including the massive 1901 “Lucas Gusher” in Texas, Mather worked little in his later years. His financial circumstances diminished with age and illness.

The Artist of Oil Creek died poor and without fanfare on August 23, 1915, in Titusville. His death certificate reported the cause as cerebral hemorrhage, “complicated by suppression of urine.”

An 1865 John Mather photograph of wooden derricks, engine houses, oilfield workers, an office (and tree stumps) at Pioneer Run – Oil Creek, Pennsylvania.

To preserve John A. Mather’s petroleum industry legacy, the Drake Well Memorial Association purchased 3,274 surviving glass negatives for about 30 cents each.

The Drake Well Museum has preserved the photographer’s surviving work. The museum and surrounding park allow visitors to explore rare artifacts and a visual record of the early U.S. oil and natural industry. Visit the Titusville museum along Oil Creek and other Pennsylvania petroleum museums.

More Resources

“Virtually unknown, certainly unheralded, and completely unappreciated — in these few words is a description of John Aked Mather, pioneer photographer, ” proclaimed Ernest C. Miller and T.K. Stratton in their January 1972 article, “Oildon’s Photographic Historian,” in The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (Volume 55, Number 1).

Born in Heapford Bury, England, in 1829, the son of an English papermill superintendent, Mather joined his two brothers in America in 1856. He soon became “transfixed by the beauty of the Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio regions,” explains a NWPaHeritage article, adding he developed an “obsessive desire to capture the industry in its entirety.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America

(2008); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America (2004); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2004); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfield Photographer John Mather.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/oilfield-photographer-john-mather. Last Updated: May 30, 2025. Original Published Date: March 11, 2005.

by Bruce Wells | May 26, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

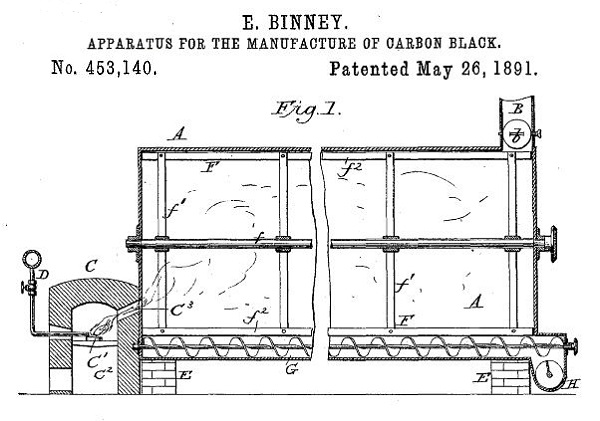

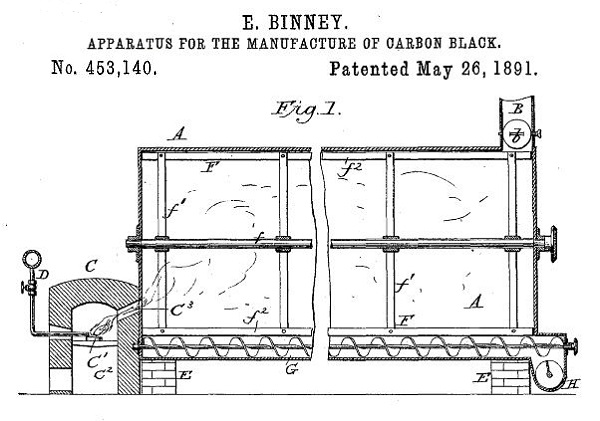

May 26, 1891 – Carbon Black Patent leads to Crayola –

Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith received a patent for an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.” The Binney & Smith process created a fine, intensely black soot-like substance — a pigment blacker than any other. Its success would lead to another petroleum product, Crayola crayons.

Edwin Binney in 1891 patented a petroleum-burning “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.” Twelve years later, Binney & Smith produced another oilfield product, Crayola, named by his wife Alice.

After introducing a popular black crayon called Staonal (stay-on-all) the Pennsylvania company began manufacturing Crayola crayons in 1903 using paraffin hand-mixed pigments. Each box contained eight colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown and black.

Learn more in Carbon Black and Oilfield Crayons. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

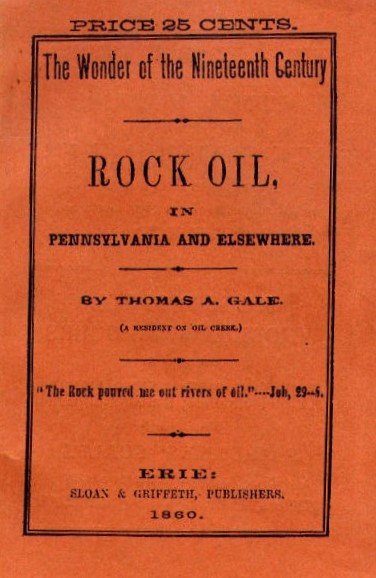

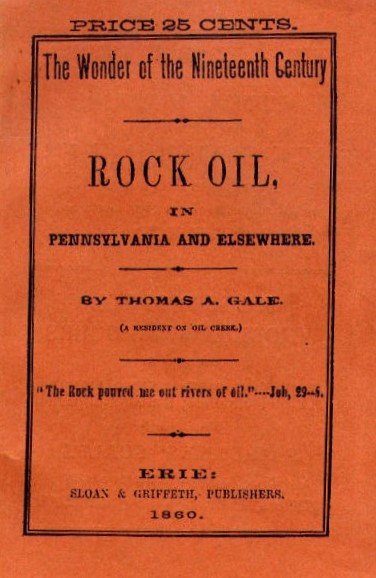

Less than 10 months after Edwin L. Drake and his driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith completed the first commercial U.S. oil well on August 27, 1859, along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Thomas A. Gale wrote a detailed study about rock oil — and helped launch the petroleum age.

Published in 1860, The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere described a radical fuel source for the popular lamp fuel kerosene, which had been made from coal for more than a decade.

“Those who have not seen it burn may rest assured its light is no moonshine; but something nearer the clear, strong, brilliant light of day,” Gale declared in his 25-cent pamphlet printed in Erie by Sloan & Griffith Company.

Thomas Gale’s 80-page pamphlet in 1860 marked the beginning of the petroleum age, illuminated with kerosene lamps.

“In other words, rock oil emits a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world; a light fit for Kings and Royalists, and not unsuitable for Republicans and Democrats,” Gale added.

Oil in Rocks

Gale’s descriptions of the value of petroleum helped launch investments in new exploration companies, especially as he noted the commercial qualities of Pennsylvania oil for refining into kerosene, the distilled “coal oil” invented in 1848 by Canadian chemist Abraham Gesner.

Historians regard the 80-page publication as the first book about America’s petroleum industry. The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere was almost forgotten until 1952, when the Ethyl Corporation of New York republished the work. Only three original copies were known to exist.

“Not by the widest stretch of the imagination could Thomas Gale have realized, when he put down his pen on June 1, 1860, that he had written a book destined to become one of the rarest of all oil books,” proclaimed the Ethyl historian when the company republished Gale’s book.

Ethyl Corporation noted the scarcity of copies of the book had prevented “all but a few historians” from giving the book the attention it deserved.

“Gale wrote his book to satisfy a public desire for more information about petroleum. Newspapers had carried belated accounts of Drake’s discovery well, and the mad scramble for oil that followed, but actually the world knew little about petroleum.”

“The Rock poured…”

The book’s 11 chapters explain practical aspects of the new petroleum industry. Chapters one and two, “What is Rock Oil?” and “Where is the Rock Oil found?” were followed by “Geological Structure of the Oil Region.”

Chapters four through six explained the early technologies (and costs) for pumping the oil, while the next two chapters examine “Uses of Rock Oil.” The final three chapters offered “Sketches of several oil wells,” “History of the Rock Oil Enterprise,” and “Present condition and prospects of Rock Oil interests in different localities.”

Chapter three in The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere features the “geological structure of the oil region,” today part of Oil Creek State Park in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Originally published by Sloan & Griffith of Erie, Pennsylvania, the 1860 cover noted the author as “a resident of Oil Creek” and included a biblical quote, “The Rock poured me out rivers of oil,” from Job, 29:6.

In addition to mysteriously burning gasses and “tar pits,” explorers for millennia have referenced signs of coal, bitumen, and substances very much like petroleum — a word derived from the Latin roots of petra, meaning “rock” and oleum meaning “oil.”

But did Thomas Gayle’s 1860 work produce the first book about oil as Ethyl Corporation historians believed when the company reprinted it in 1952? In fact, there have been many references to natural oil seeps recorded millennia ago (including in the Bible), according to a geologist who has researched the earliest sightings of petroleum.

Illuminating Petroleum

Several years before the 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, businessman George Bissell hired a prominent Yale chemist to study the potential of oil and its products to convince potential investors (see George Bissell’s Oil Seeps).

“Gentlemen, it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products,” reported Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1855.

Silliman’s groundbreaking “Report on the Rock Oil, or Petroleum, from Venango Co., Pennsylvania, with Special Reference to its Use for Illumination and Other Purposes,” convinced the petroleum industry’s earliest investors to drill at Titusville. Cable-tool technology developed for brine wells would drill the well.

According to historian Paul H. Giddens in the 1939 classic, The Birth of the Oil Industry, Silliman’s 1855 report, “proved to be a turning-point in the establishment of the petroleum business, for it dispelled many doubts about its value.”

The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company would evolve into the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut, which became America’s first oil company after Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well drilled seeking oil in 1859.

Rock Oil Products

In addition to providing oil for refining into kerosene lamps (and someday rockets), oilfield discoveries led to many products. Early petroleum products included axle greases, an oilfield paraffin balm, and in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons.

Further, oil offered an improved asphalt prior to the first U.S. auto show in November 1900 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

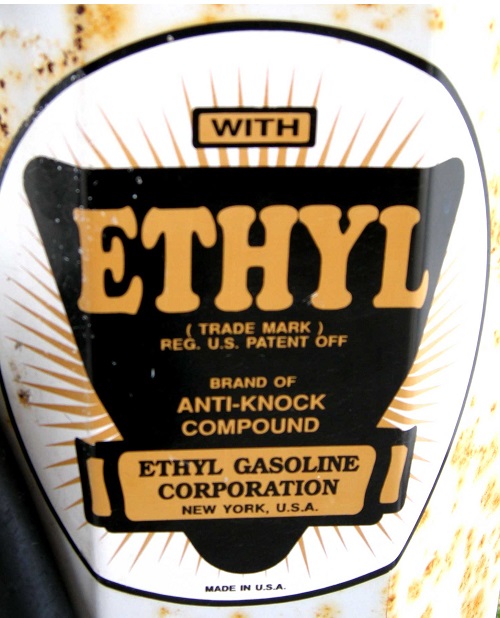

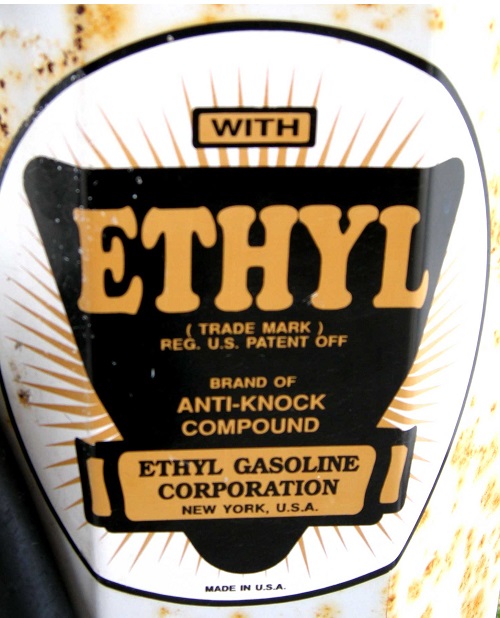

Ethyl Corporation was established in 1923 by General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey,

Responding to consumer demand for better automobile gasoline, General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey established the Ethyl Corporation in 1923. The company initially downplayed the danger of tetraethyl lead. Leaded gas would be banned for use in cars in the 1970s

Importantly, high-octane leaded aviation fuel proved vital for victory in World War II — and the additive still fuels many piston-engine aircraft and racecars.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere (1952); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1939); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Oil Book of 1860.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/first-oil-book-of-1860. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: May 31, 2020.

(2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.