by Bruce Wells | Jun 16, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

June 16, 1903 – Ford Motor Company Incorporated –

After successfully testing his gasoline-powered Quadricycle in 1896, Henry Ford and a group of investors (including machinist John Dodge) filed articles of association for the Ford Motor Company. Ford’s contributions included machinery, drawings, and several patents. The first sale was a Ford Model A to a Chicago physician in July as the Detroit-based automaker began ordering carriages, wheels, and tires for a low-cost car that would become the Model T by 1908, according to the Henry Ford Heritage Association (HFHA).

June 18, 1889 – Standard Oil of New Jersey adds Indiana

Standard Oil Company of New Jersey incorporated a subsidiary, Standard Oil Company of Indiana, and began processing oil at its new refinery in Whiting, Indiana, southeast of Chicago. In 1910, the refinery added pipelines connecting it to Kansas and Oklahoma oilfields. When the Supreme Court mandated the break up of John D. Rockefeller’s empire in 1911, Standard Oil of Indiana emerged as an independent company. Amoco branded service stations arrived in the 1950s. Amoco merged with British Petroleum (BP) in 1998, the largest foreign takeover of a U.S. company at the time.

June 18, 1946 – Truman establishes National Petroleum Council

At the request of President Harry S. Truman, the Department of the Interior established the National Petroleum Council to make policy recommendations relating to oil and natural gas. Transferred to the new Department of Energy in 1977, the Council became a privately funded advisory committee with 200 members appointed by the Secretary of Energy. “The NPC does not concern itself with trade practices, nor does it engage in any of the usual trade association activities,” notes the NPC, which held its 134th meeting on April 23, 2024, in Washington, D.C.

June 18, 1948 – Service Company celebrates 100,000th Perforation

Fifteen years after its first well-perforation job, the Lane-Wells Company returned to the well at Montebello, California, to perform its 100,000th perforation. The return to Union Oil Company’s La Merced No. 17 well included a ceremony hosted by Walter Wells, chairman and company co-founder.

Los Angeles headquarters of Lane-Wells by architect William Mayer, completed in 1937. Photo courtesy Water and Power Associates.

In 1930, Wells and oilfield tool salesman Bill Lane developed a practical multiple-shot perforator that could shoot steel bullets through casing. After many tests, success came at the La Merced No. 17 well. By late 1935, Lane-Wells established a small fleet of trucks for well-perforation services. The company merged with Dresser Industries in 1956 and later became part of Baker-Atlas.

Learn more in Lane-Wells 100,000th Perforation.

June 20, 1977 – Oil begins Flowing in Trans-Alaska Pipeline

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline began carrying oil 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to the Port of Valdez at Prince William Sound. The oil arrived 38 days later, culminating the world’s largest privately funded construction project. The Prudhoe Bay field had been discovered in 1968 by Atlantic Richfield and Exxon about 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Construction of the controversial pipeline began in 1974. Photo courtesy Alaska Pipeline Authority.

After years of controversy, construction of the 48-inch-wide pipeline began in April 1974. Above-ground sections of the pipeline (420 miles) were built in a zigzag configuration to allow for expansion or contraction and include heat pipes. Oil throughput of the $8 billion pipeline peaked in 1988 at just over 2 million barrels per day, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), adding that since 2003, deliveries have been less than 1 million barrels per day and averaged a record low of 464,748 barrels per day in 2024.

“That creates challenges for the pipeline’s operators, including the formation of ice and the buildup of wax that is in the oil on the inside pipeline wall, EIA notes. “The amount of time it takes for oil to travel the 800 miles through the pipeline from the North Slope to the Valdez port increased from 4.5 days in 1988 to about 19 days in recent years.”

Learn more in Trans-Alaska Pipeline History.

June 21, 1893 – Submersible Pump Inventor born

Armais Arutunoff, inventor of the electric submersible pump for oil wells, was born to Armenian parents in Tiflis, Russia. He invented the world’s first electrical centrifugal submersible pump in 1916. At first, Arutunoff could not find financial support for his oilfield production technology after emigrating to the United States in 1923.

Russian engineer Armais Arutunoff, inventor of the first electric submersible pumps.

Thanks to help from Frank Phillips, president of Phillips Petroleum, Arutunoff moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1928 and established a manufacturing company. The Tulsa World described the Arutunoff pump as “An electric motor with the proportions of a slim fencepost which stands on its head at the bottom of a well and kicks oil to the surface with its feet.”

REDA Pump Company manufactured pump and motor devices — and employed hundreds during the Great Depression. The name stands for Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff, the cable address of his first company in Germany and since 1998 a subsidiary of SLB (Schlumberger).

Learn more in Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump.

June 21, 1932 – Oklahoma Governor battles “Hot Oil”

Thirty National Guardsmen marched into the Oklahoma City oilfield when Governor William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray took control of oil production after creating a proration board despite objections from independent producers.

The Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City includes petroleum equipment on display in the Devon Energy Park, which opened in 2005. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Murray declared martial law again in March 1933 to enforce his regulations preventing the sale or transport of oil produced in excess of the quota, referred to as “hot oil.”

The state legislature passed a law in April giving the Oklahoma Corporation Commission authority to enforce its rules — taking away Murray’s power to regulate the petroleum industry. The commission had been established in 1907 to regulate railroad, telephone, and telegraph companies.

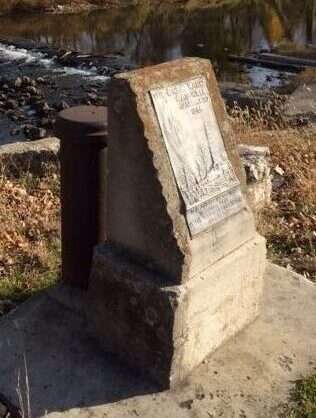

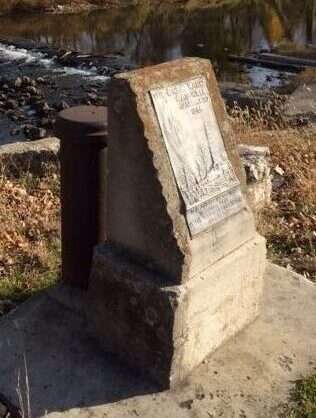

June 21, 1937 – “Great Karg Well” Marker dedicated in Ohio

Similar to the Indiana natural gas boom, discoveries in Ohio brought petroleum prosperity as evidenced by a 1937 historic marker at one well — “erected in humble pride by the people of Findlay, Ohio,” in celebration of the “Great Karg Well” that revealed a giant natural gas field in January 1886.

Marker dedicated in 1937 at the wellhead of the famous 1886 natural gas discovery at Findlay, Ohio. Photo by Michael Baker, courtesy Historical Marker Database.

“At that time gas was simply a by-product of oil drilling, and with no way to store it they ended up piping it away for free to heat homes and drive industrial machinery,” notes the historic marker inscription at the wellhead. Many companies promoted Ohio’s natural gas supplies, which “attracted glass companies from around the world” — until the gas ran out.

Learn more in Indiana Natural Gas Boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: From Here to Obscurity: An Illustrated History of the Model T Ford, 1909 – 1927 (1971); Standard Oil Company: The Rise and Fall of America’s Most Famous Monopoly

(1971); Standard Oil Company: The Rise and Fall of America’s Most Famous Monopoly (2016); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2016); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields

(2008); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields (1990)

(1990) ; The Great Alaska Pipeline

; The Great Alaska Pipeline (1988); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems

(1988); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems (1984); Oil in Oklahoma

(1984); Oil in Oklahoma (1976); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America

(1976); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025. Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 11, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Armais Arutunoff designed a downhole centrifugal pump and founded an oilfield service company.

The modern petroleum industry owes a lot to the son of an Armenian soap maker who invented an artificial lift system using an electric motor to drive a centrifugal pump at the well.

With the help of the Phillips Petroleum Company in the 1930s, Armais Sergeevich Arutunoff moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and built the earliest practical downhole electric submersible pump. His invention would enhance oilfield production in wells worldwide.

Armais Arutunoff (1893-1978), inventor of the modern electric submersible pump.

A 1936 Tulsa World article described the Arutunoff electric submersible pump (ESP) as “an electric motor with the proportions of a slim fence post which stands on its head at the bottom of a well and kicks oil to the surface with its feet.”

By 1938, an estimated two percent of all oil produced in the United States with artificial lift used an Arutunoff pump (see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology).

Early Downhole Patents

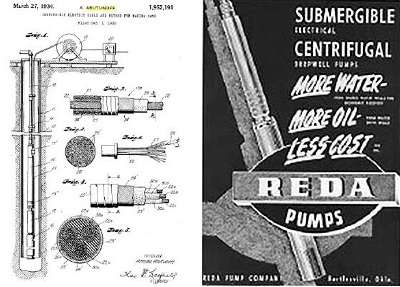

The first U.S. patent for an oil-related electric pump arrived in the late 19th century during the growth of electrical power generation, according to a 2014 article in the Journal of Petroleum Technology (JPT).

In 1894, a design by Harry Pickett (patent no. 529,804) used a downhole rotary electric motor with “a Yankee screwdriver device to drive a plunger pump.” Expanding Picket’s concept, Robert Newcomb in 1918 received a patent for his “electro-magnetic engine” driving a reciprocating plunger.

“Heretofore, in very deep wells the rod that is connected to the piston, and generally known as the ‘sucker’ rod, very often breaks on account of its great length and strains imposed thereon in operating the piston,” noted Newcomb in his patent application.

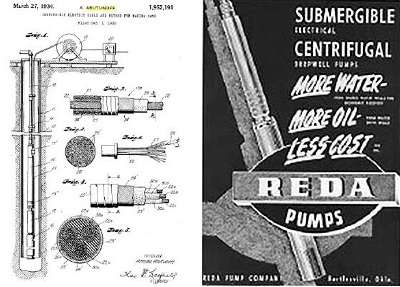

Armais Arutunoff obtained 90 patents, including one in 1934 for an improved well pump and electric cable. At right is a 1951 “submergible” Reda advertisement.

Although several patents followed those of Picket and Newcomb, the Journal reports, “It was not until 1926 that the first patent for a commercial, operatable ESP was issued — to ESP pioneer Armais Arutunoff. The cable used to supply power to the bottomhole unit was also invented by Arutunoff.”

Reda: Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff

Arutunoff built his first ESP in 1916 in Germany, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. “Suspended by steel cables, it was dropped down the well casing into oil or water and turned on, creating a suction that would lift the liquid to the surface formation through pipes,” reported OHS historian Dianna Everett.

After immigrating to the United States in 1923, in California Arutunoff could not find financial support for manufacturing his pump design. He moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1928 at the urging of a new friend — Frank Phillips, head of Phillips Petroleum Company.

“With Phillips’s backing, he refined his pump for use in oil wells and first successfully demonstrated it in a well in Kansas,” noted Everett. The small company that became Reda Pump manufactured the device.

The name Reda – Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff – derived from the cable address of the company that Arutunoff originally started in Germany. The inventor would move his family into a Bartlesville home just across the street from Frank Phillips’ mansion.

The founder of Reda Pump once lived in this Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home across from Frank Phillips, whose home today is a museum. Photo courtesy Kathryn Mann, Only in Bartlesville.

A holder of more than 90 patents in the United States, Arutunoff was elected to the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1974. “Try as I may, I cannot perform services of such value to repay this wonderful country for granting me sanctuary and the blessings of freedom and citizenship,” Arutunoff said at the time.

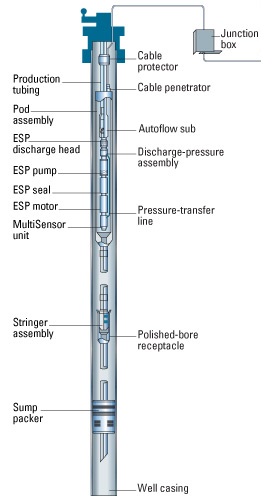

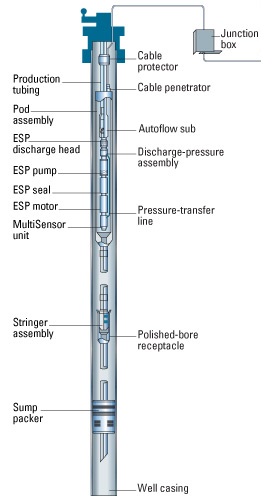

Artificial lift spins the impellers on the pump shaft, putting pressure on the surrounding fluids and forcing them to the surface. Image courtesy Schlumberger.

Arutunoff died in February 1978 in Bartlesville. At the end of the 20th century, Reda ranked as the world’s largest manufacturer of ESP systems. It is now part of Schlumberger.

Armais Sergeevich Arutunoff was born to Armenian parents in Tiflis, part of the Russian Empire, on June 21, 1893. His hometown in the Caucasus Mountains dates back to the 5th Century. His father manufactured soap; his grandfather earned a living as a fur trader.

Centrifugal Pumps

As a young scientist, Arutunoff’s research convinced him that electrical transmission of power could be efficiently applied to oil drilling and improve the production methods he saw in use in the early 1900s in Russia.

Downhole production would require a powerful electric motor, but limitations imposed by the available casing sizes required a new kind of motor.

A small-diameter motor had too little horsepower for the job, Arutunoff discovered. He studied the fundamental laws of electricity seeking answers to how to build a higher horsepower motor exceedingly small in diameter.

By 1916, Arutunoff designed a centrifugal pump to be coupled to the motor for de-watering mines and ships. To develop enough power, the motor needed to run at very high speeds. He successfully designed a centrifugal pump, small in diameter and with stages to achieve high discharge pressure.

Arutunoff designed a motor ingeniously installed below the pump to cool the motor with flow moving up the oil well casing. The entire unit could be suspended in the well on the discharge pipe. The motor, sealed from the well fluid, operated at high speed in the oil.

Although Arutunoff built the first centrifugal pump while living in Germany, he built the first submersible pump and motor in the United States while living in southern California.

Friend of Frank

Arutunoff already had formed Reda to manufacture his idea for electric submersible motors, and after living in Germany, Arutunoff came to the United States with his wife and one-year-old daughter to settle in Michigan, and then Los Angeles.

However, after emigrating to America in 1923, Arutunoff could not find financial support for his downhole production technology. Everyone he approached turned him down, believing his downhole concept impossible under the “laws of electronics.”

No one would consider his inventions until a friend at Phillips Petroleum Company — Frank Phillips — encouraged him to form his own company in Bartlesville. The Arutunoff family moved into a house on the same street as the Phillips home.

Arutunoff’s manufacturing plant in Bartlesville spread over nine acres, employing hundreds during the Great Depression.

In 1928 Arutunoff moved to Bartlesville, where he formed Bart Manufacturing Company, which changed its name to Reda Pump Company in 1930. He soon demonstrated a working model of an oilfield electric submersible pump.

Upside down Motors

One of his pump-and-motor devices produced oil at well in the El Dorado field near Burns, Kansas — the first equipment of its kind to be used downhole. One reporter telegraphed his editor, “Please rush good pictures showing oil well motors that are upside down.”

By the end of the 1930s, Arutunoff’s company held dozens of patents for industrial equipment, leading to decades of success — and still more patents. His “Electrodrill” aided scientists in penetrating the Antarctic ice cap for the first time in 1967.

Arutunoff oilfield technologies had a significant impact on the petroleum industry — quickly proving crucial to successful production for hundreds of thousands of U.S. oil wells.

Also see Conoco & Phillips Petroleum Museums.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems (1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum

(1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum (2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/electric-submersible-pump-inventor. Last Updated: June 12, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 7, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

April 7, 1902 – Spindletop Boom brings The Texas Company –

Joseph “Buckskin Joe” Cullinan and Arnold Schlaet established The Texas Company in Beaumont to transport and refine oil from Spindletop Hill, a giant oilfield discovered in January 1901. The new company constructed a kerosene refinery in Port Arthur — and discovered an oilfield at Sour Lake Springs, where its Fee No. 3 well produced 5,000 barrels of oil a day in 1903.

The National Route 66 Museum in Elk City, Oklahoma, preserves the heritage of Texaco, the first petroleum company to market products in all 50 states. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Texas Company telegraph address at its New York office was “Texaco,” a name soon adopted for its petroleum products. In 1909 a red star with a green capital “T” was trademarked and by 1928 the Texaco brand operated more than 4,000 service stations nationwide. The Texas Company, which officially renamed itself Texaco in 1959, was acquired by Chevron in 2001.

Learn more in Sour Lake produces Texaco.

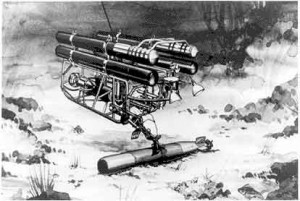

April 7, 1966 – Cold War Accident boosts Offshore Technology

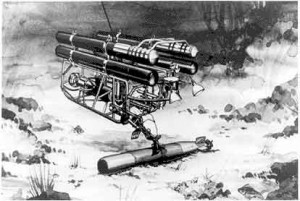

A robotic technology soon adopted by the offshore petroleum industry was first used to retrieve an atomic bomb. America’s first cable-controlled underwater research vehicle (CURV) attached cables to recover the weapon lost in the Mediterranean Sea.

The U.S. Navy in 1966 used its CURV (Cable-Controlled Underwater Recovery Vehicle) to recover a lost nuclear bomb in the Mediterranean.

The 70-kiloton hydrogen bomb, which had been lost when a B-52 crashed off the coast of Spain in January, was safely hoisted from a depth of 2,850 feet.

“It was located and fished up by the most fabulous array of underwater machines ever assembled,” proclaimed Popular Science magazine. During the Cold War, the Navy developed deep-sea technologies that the offshore petroleum industry would adopt and continue to advance.

Learn more in ROV – Swimming Socket Wrench.

April 8, 1929 – Sinclair vs. United States

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld a lower court ruling that Congress had the right to investigate Sinclair Oil founder Harry Sinclair’s personal dealings with Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall regarding the leasing of federal oil reserves. In 1922, Fall had leased land in the Teapot Dome oilfield (Navy Reserve No. 3) to the Mammoth Oil Company, a Sinclair subsidiary. He also leased land in California’s Elk Hills reserve to Edward Doheny, the 1892 discoverer of the Los Angeles Field.

After several trials, proceedings concluded with Doheny being acquitted of conspiracy and Fall convicted of accepting bribes and serving nine months in prison, notes the Federal Judicial Center. He was the first cabinet official to go to prison. Sinclair was acquitted of conspiracy but convicted of contempt of Congress and served six and a half months in prison in 1929.

April 9, 1914 – Ohio Cities Gas Company founded

Beman Dawes and Fletcher Heath organized the Ohio Cities Gas Company in Columbus, Ohio, before building an oil refinery in West Virginia. Ohio Cities Gas acquired Pennsylvania-based Pure Oil Company in 1917 and adopted that name three years later. Pure Oil was founded in Pittsburgh in 1895 by independent oil producers, refiners, and pipeline operators to counter the market dominance of Standard Oil Company.

Ohio Cities Gas Company became Pure Oil in 1917.

By producing, refining and selling its products, Pure Oil became the second vertically integrated petroleum company after Standard Oil. Headquartered in a now iconic Chicago skyscraper it built in 1926, the company joined the 100 largest U.S. industrial corporations. It was acquired in 1965 by Union Oil Company of California, now a division of Chevron.

April 9, 1966 – Birthday of Tula’s Golden Driller

A 76-foot statue of an oilfield worker today known as “The Golden Driller” made its debut at the International Petroleum Exposition in Tulsa, Oklahoma. After several refurbishments, the 22-ton statue would contain 2.5 miles of rods and mesh with tons of plaster and concrete — withstanding winds up to 200 mph. A smaller version of Tulsa’s iconic roughneck originally appeared at the 1953 petroleum exposition as a promotion for the Mid-Continent Supply Company of Fort Worth, Texas.

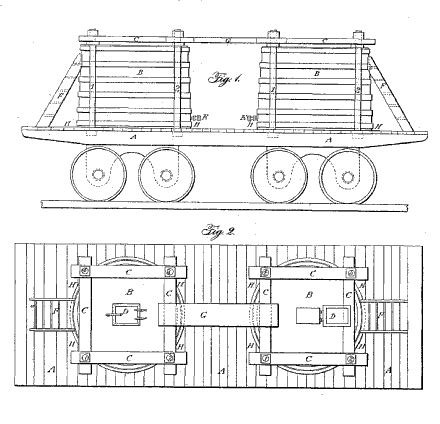

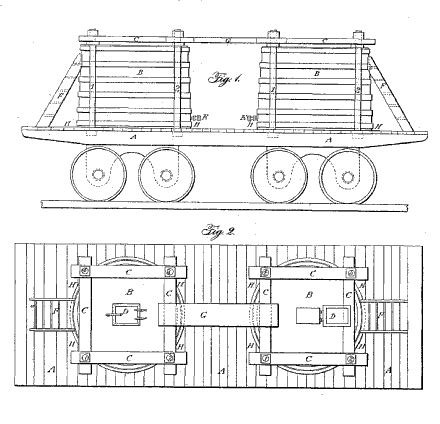

April 10, 1866 – Densmore Brothers patent Railroad Oil Tank Car

James and Amos Densmore of Meadville, Pennsylvania, received a patent for their “Improved Car for Transporting Petroleum,” developed a year earlier in the northwestern Pennsylvania oil regions. Their patent illustrated a simple but sturdy design for securing two re-enforced containers on a typical railroad car.

The Densmore dual tank car briefly revolutionized the bulk transportation of oil to market. Hundreds of the twin tank railroad cars were in use by 1866.

Although the Densmore cars were an improvement, they would be replaced by the more practical single, horizontal tank. After leaving the business, Amos Densmore in 1875 invented a new way for arranging “type writing machines” so commonly used letters would not collide — the “Q-W-E-R-T-Y” keyboard. James Densmore’s continued success in oilfields helped finance the start of the Densmore Typewriter Company.

Learn more in Densmore Brothers invent First Oil Tank Car.

April 11, 1957 – Independent Producer William Skelly dies

William Grove Skelly (1878 -1957) died in Tulsa after a long career as an independent producer he began as a 15-year-old tool dresser in early Pennsylvania oilfields. Prior to World War I, he found success in the El Dorado field outside Wichita, Kansas. Skelly incorporated Skelly Oil Company in Tulsa in 1919. In 1923, Skelly organized the first International Petroleum Exposition while serving as president of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce. Skelly in 1947 helped establish KWGS, Tulsa’s first FM radio station and one of the earliest educational stations in the nation.

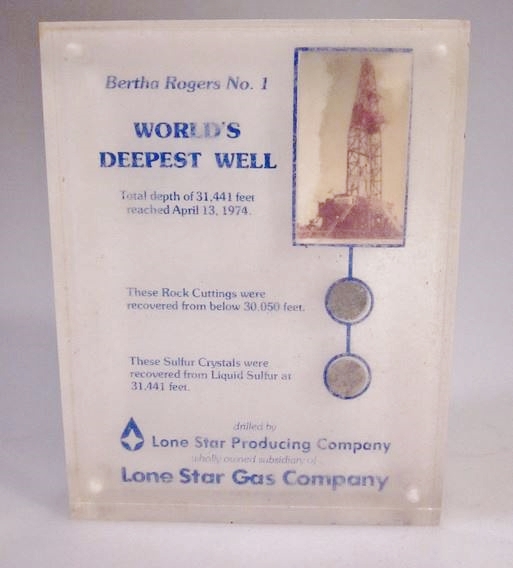

April 13, 1974 – Depth Record set in Oklahoma Anadarko Basin

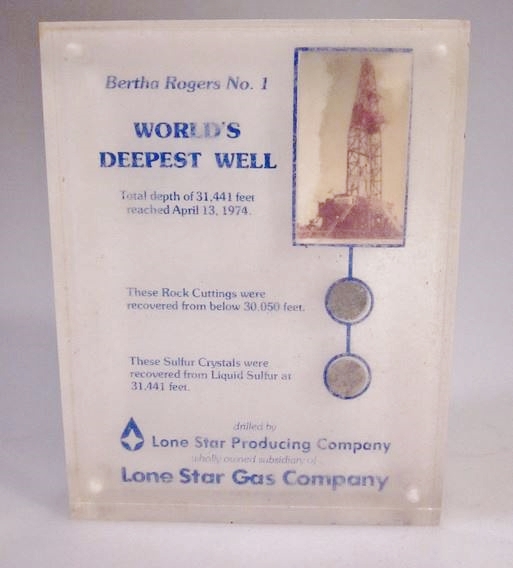

After drilling for 504 days and spending about $7 million, the Bertha Rogers No. 1 well reached a total depth of 31,441 feet (5.95 miles) before being stopped by liquid sulfur. Drilled in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin, it held the record of the world’s deepest well for more than a decade.

The GHK Company of Robert Hefner III and partner Lone Star Producing Company believed natural gas reserves resided deep in the Anadarko Basin extending across West-Central Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle. Their first high-tech drilling attempt began in 1967 and took two years to reach a then record depth of 24,473 feet.

A 1974 souvenir plaque of the Bertha Rogers No. 1 well, which reached almost six miles deep in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin.

The 1969 well found plenty of natural gas, according to historian Robert Dorman, but because of federal price controls, “the sale of the gas could not cover the high cost of drilling so deeply – $6.5 million, as opposed to a few hundred thousand dollars for a conventional well.”

The drilling of the Bertha Rogers well began in November 1972 and averaged about 60 feet per day. By April 1974, bottom-hole pressure reached almost 25,000 pounds per square inch with a temperature of 475 degrees. The well’s 1.5 million pounds of casing was the heaviest ever handled by a drilling rig, and it took eight hours for cuttings to reach the surface.

Learn more in Anadarko Basin in Depth.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Texaco Story: The First Fifty Years, 1902-1952 (2012); Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science

(2012); Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science (2002); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America

(2002); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America (2000); Oil in Oklahoma

(2000); Oil in Oklahoma (1976); History Of Oil Well Drilling

(1976); History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 2, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Giant Oklahoma rigs drilled to record depths in the 1970s.

The Anadarko Basin, extending more than 50,000 square miles across west-central Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle, includes some of the most prolific U.S. natural gas reserves — and a 1974 drilling record.

Beginning in the late 1950s, when technological advances allowed it, Anadarko Basin wells in Oklahoma began to be drilled more than two miles deep in search of natural gas. Dangerous, highly pressurized formations required state-of-the-art blowout preventers (see Ending Oil Gushers — BOP). (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Mar 19, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Featured in newsreels, an Oklahoma City 1930 gusher needed “clever equipment” to be brought under control.

As the worst of the Great Depression approached, an 11-day geyser of Oklahoma “black gold” was irresistible to newspaper editors and newsreel producers in 1930. Crews from NBC Radio rushed to cover the dramatic struggle to control “Wild Mary Sudik,” a blowout in the Oklahoma City oilfield. Repeated attempts to contain the well made headlines.

The Mary Sudik No. 1 well erupted after striking a high-pressure formation about 6,500 feet beneath the farm of Vincent and Mary Sudik near the intersection of Bryant Street and present-day I-240 in southwest Oklahoma City. The Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company’s well flowed a “volcano of crude oil and natural gas” for 11 days before being brought under control. (more…)

(1971); Standard Oil Company: The Rise and Fall of America’s Most Famous Monopoly

(2016); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2008); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields

(1990)

; The Great Alaska Pipeline

(1988); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems

(1984); Oil in Oklahoma

(1976); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.