by Bruce Wells | Oct 26, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Oilfield service company founder and future mayor of Toledo patented a “Coupling for Pipes or Rods” in 1894.

Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones of Ohio made a fortune in oilfields and supplying equipment and services, patented an improved sucker rod for pumping oil, and created a better workplace for his factory employees. He ran on the progressive Republican ticket in 1897 and was elected mayor of Toledo. He would be reelected three times.

As the country weathered an 1890s financial crisis, Samuel M. Jones brought a new business philosophy to Toledo, Ohio. An immensely popular mayor, he was reelected in 1899, 1901, and 1903 — and served in office until dying on the job in 1904.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jul 23, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Oilfield service provider Zero Hour Bomb Company in 1949 introduced its “cannot backlash” fishing reel.

Zebco oilfield history began well before 1947 when Jasper R. Dell Hull walked into the Tulsa offices of the Zero Hour Bomb Company. The amateur inventor from Rotan, Texas, carried a piece of plywood with nails arranged in a circle wrapped in line. His device included a coffee-can lid that could spin.

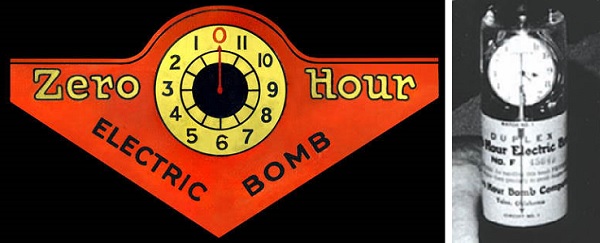

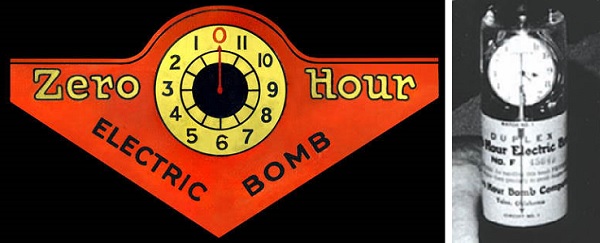

Hull, known by his friends as “R.D.,” had an appointment with executives at the Oklahoma oilfield service company. Incorporated in 1932, the Zero Hour Bomb Company was a leading manufacturer of dependable electric timer bombs used for fracturing geologic formations. The company designed and patented innovative technologies for “shooting” wells to increase oil and natural gas production.

In 1932, the oilfield service company Zero Hour Bomb Company began manufacturing electric time bombs in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Photos courtesy Zebco.

Zero Hour Bomb Company’s timer controlled a mechanism with a detonator inside a watertight casing. The downhole device could be pre-set to detonate a series of blasting caps, which set off the well’s main charge, shattering rock formations.

Hull’s 1947 visit proved timely for Zero Hour Bomb Company, because post World War II demand for its electrically triggered devices had declined. With the military no longer needing oil to fuel the war, the U.S. petroleum industry faced a major recession.

The company and other once booming Oklahoma service companies were reeling, and the future did not look good.

“Vast fossil fuel reserves beneath other Middle Eastern nations were being unlocked,” noted journalist Joe Sills in a 2014 article. With OPEC beginning to take shape, Texas and Oklahoma-based oil production could only look forward to taking “a decades-long backseat to foreign oil.”

Further, with company patents expiring in 1948, “the Zero Hour Bomb Company needed a solution,” explained Sills, an editor for Fishing Tackle Retailer. After examining Hull’s contraption, a prototype fishing reel, the company hired him for $500 a month.

Meanwhile, as “fishing” petroleum wells helped recover downhole tools, Hull received a patent that transformed the Zero Hour Bomb Company — and sport fishing in America.

Downhole Patents

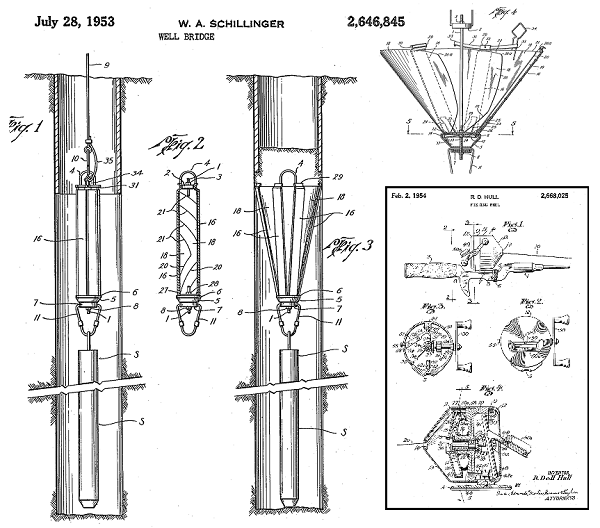

Beginning in the early 1930s, Zero Hour Bomb engineers patented many innovative oilfield products. A 1939 design for an “Oil Well Bomb Closure” facilitated the assembly of an explosive device capable of withstanding extreme pressures submerged deep in a well.

A 1940 innovation provided a hook mechanism for safely lowering torpedoes into wells. The locking method could “positively prevent premature release of the torpedo while it is being lowered into the well.”

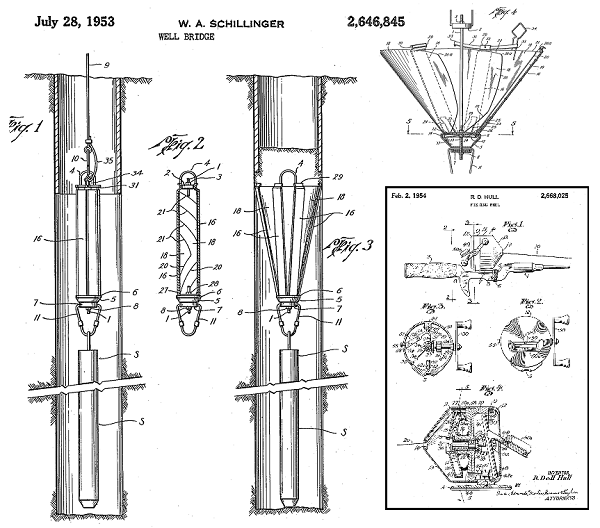

The July 28, 1953, patent for a canvas “well bridge” would be among the last Zero Hour Bomb Company received as an oilfield equipment manufacturer, thanks to R.D. Hull’s late-1940s design for a fishing reel (insert) illustrated in his February 2, 1954, patent.

The separate patent in 1941 improved positioning blasting cartridges using a plugging device made of canvas. It looked like an upside-down umbrella that automatically opened, “when the time bomb or weight reached a position at the bottom of the well.”

In 1953, an improved “well bridge” design took the concept even further, but it would be the last patent Zero Hour Bomb received as an oilfield equipment manufacturer. By then, the earliest model of Hull’s new “cannot backlash” reel attracted large crowds at sports shows.

Zebco Reels

“After trying to design ‘brakes’ for bait-casting reels, and even failing at launching one fishing reel company, Hull hit on a better way one day as he watched a grocery store clerk pull string from a large fixed spool to wrap a package,” reported Lee Leschper in a 1999 Amarillo Globe-News article.

Zero Hour Bomb Company’s first “cannot backlash” reel made its public debut at a Tulsa sports expo in June 1949.

Hull realized he needed a cover to keep the line from spinning off the reel itself and soon developed a prototype, Leschper noted.

“Zero Hour officials asked two company employees who were avid fishermen for their opinions on the reel,” Leschper explained. “One tied his set of car keys to the end of the line and sent a cast flying through one of the windows in the plant. The other sent a cast high over the building. All were impressed.”

Given his own Hull-designed fishing reel at about age six, Leschper recalled, the “tiny black pushbutton reel” came with 6 lb. monofilament line (see Nylon, A Petroleum Polymer) and a four-foot hollow fiberglass rod. His small rig included a hard, yellow plastic practice plug. “I wore it down to a nub pitching it across the hard-baked grass in our front yard.”

White House security officials in 1956 quickly submerged in water a Zero Hour Bomb Company package addressed to President Eisenhower. Photo courtesy Fishing Tackle Retailer magazine.

Earlier, Hull had tested several designs before developing a manufacturing process; the first reel debuted on May 13, 1949. Called the Standard, it made its public debut at a Tulsa sports expo in June. By 1954, the reel included the simple push-button system used today.

In 1961, Brunswick Corporation acquired Zebco — and introduced the 202 ZeeBee Spincast, “an instant classic.”

White House Insecurity

The regional marketing name — Zebco — became popular, but the bottom of each reel’s foot remained stamped with the name of the manufacturer: Zero Hour Bomb Company. The official name change to Zebco came in 1956 — soon after a friend of President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked the company to send a reel to the president.

According to a Zebco company history, when White House security officers saw the package labeled “Zero Hour Bomb Company,” they plunged it into a tub of water and called the bomb squad. After changing its name to Zebco, the company left the oilfield for good.

Jasper R. Dell “R.D.” Hull joined the Sporting Goods Industry Hall of Fame in 1975 after receiving more than 35 patents. At the time of his induction, 70 million Zebco reels had been sold. He retired from the former oilfield time-bomb company in January 1977 after being diagnosed with cancer and died in December at age 64.

___________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Zebco Reel Oilfield History.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/zebco-reel-oilfield-history. Last Updated: July 23, 2025. Original Published Date: February 20, 2018.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 13, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

As the U.S. petroleum industry expanded following the January 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill in Texas, service company pioneers like Carl Baker and Howard Hughes brought new technologies to oilfields.

Baker Oil Tools and Hughes Tools specialized in maximizing petroleum production, as did oilfield service company competitors Schlumberger, a French company founded in 1926, and Halliburton, which began in 1919 as a well-cementing company.

R.C. “Carl” Baker Sr.

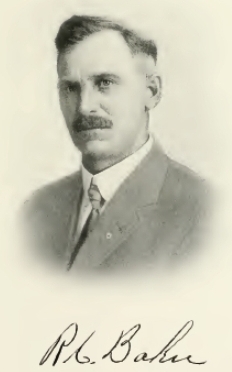

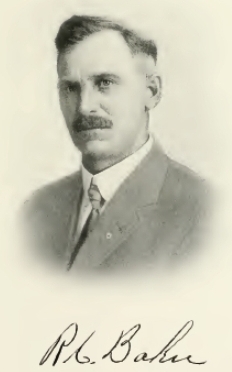

Baker Oil Tool Company (later Baker International) had been founded by Reuben Carlton “Carl” Baker Sr., who among other inventions patented a cable-tool drill bit in 1903 after founding the Coalinga Oil Company in Coalinga, California.

A 1919 portrait of Baker Tools Company founder R.C. “Carl” Baker (1872 – 1957).

The oil wells Carl Baker had drilled near Coalinga encountered hard rock formations that caused problems with casing, so he developed an offset cable-tool bit allowing him to drill a hole larger than the casing. He also patented a “Gas Trap for Oil Wells” in 1908, a “Pump-Plunger” in 1914, and a “Shoe Guide for Well Casings” in 1920.

Coalinga was “every inch a boom town and Mr. Baker would become a major player in the town’s growth,” according to the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum. He also organized several small oil companies and the local power company and established a bank.

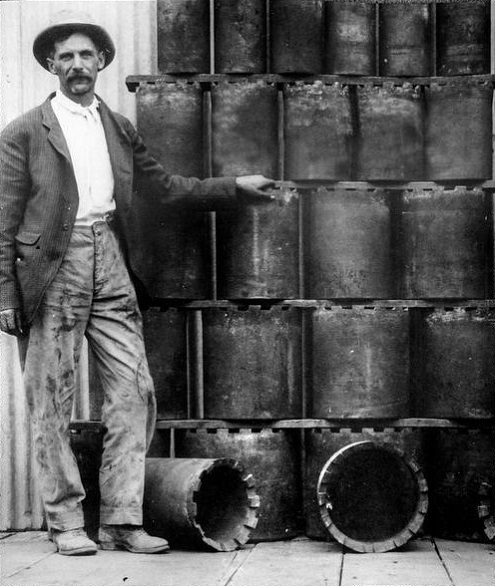

After drilling wells in the Kern River oilfield, Baker added to his technological innovations on July 16, 1907, when he was awarded a patent for his Well Casing Shoe (No. 860,115), a device ensuring uninterrupted flow of oil through a well. His invention revolutionized oilfield production.

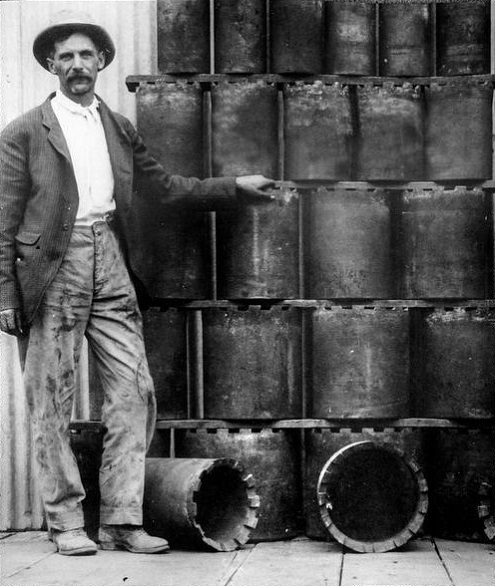

R.C. “Carl” Baker standing next to Baker Casing Shoes in 1914. Photo courtesy R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

In 1913, Baker organized the Baker Casing Shoe Company (renamed Baker Tools two years later). He opened his first manufacturing plant in Coalinga.

When Baker Tools headquarters moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, the building remained a company machine shop. It was donated by Baker to Coalinga in 1959. Two years later, the original machine shop and office of Baker Casing Shoe reopened as the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

By the time Carl Baker Sr. died in 1957 at age 85, he had been awarded more than 150 U.S. patents in his lifetime. “Though Mr. Baker never advanced beyond the third grade, he possessed an incredible understanding of mechanical and hydraulic systems,” reported the former Coalinga museum.

Baker Tools became Baker International in 1976 and Baker Hughes after the 1987 merger with Hughes Tool Company.

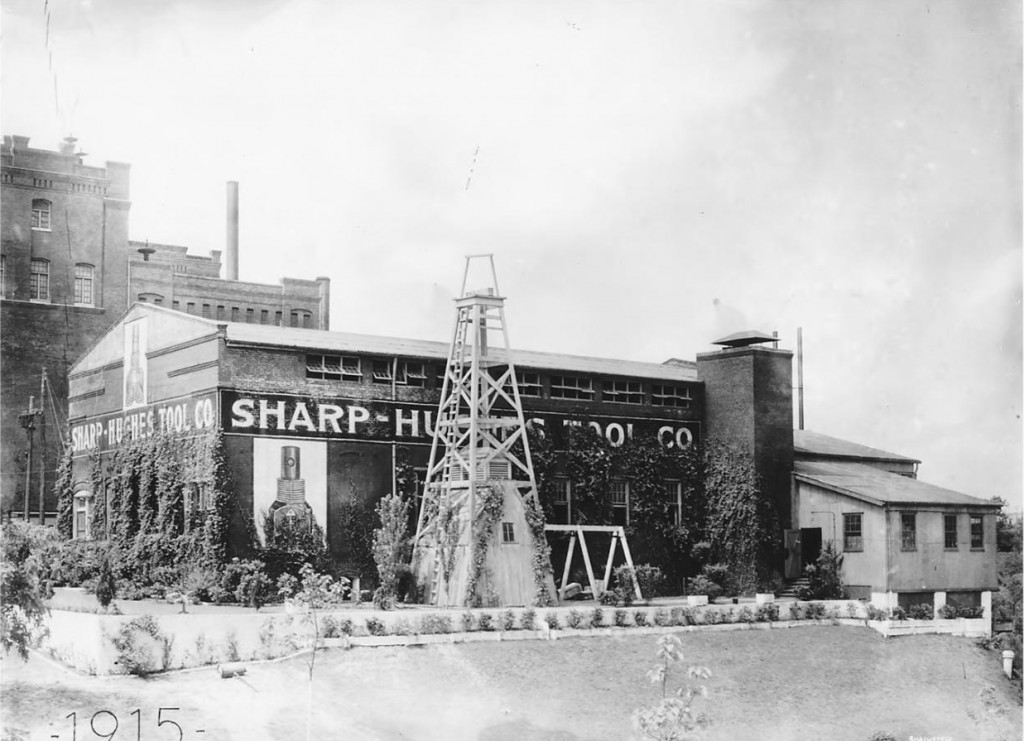

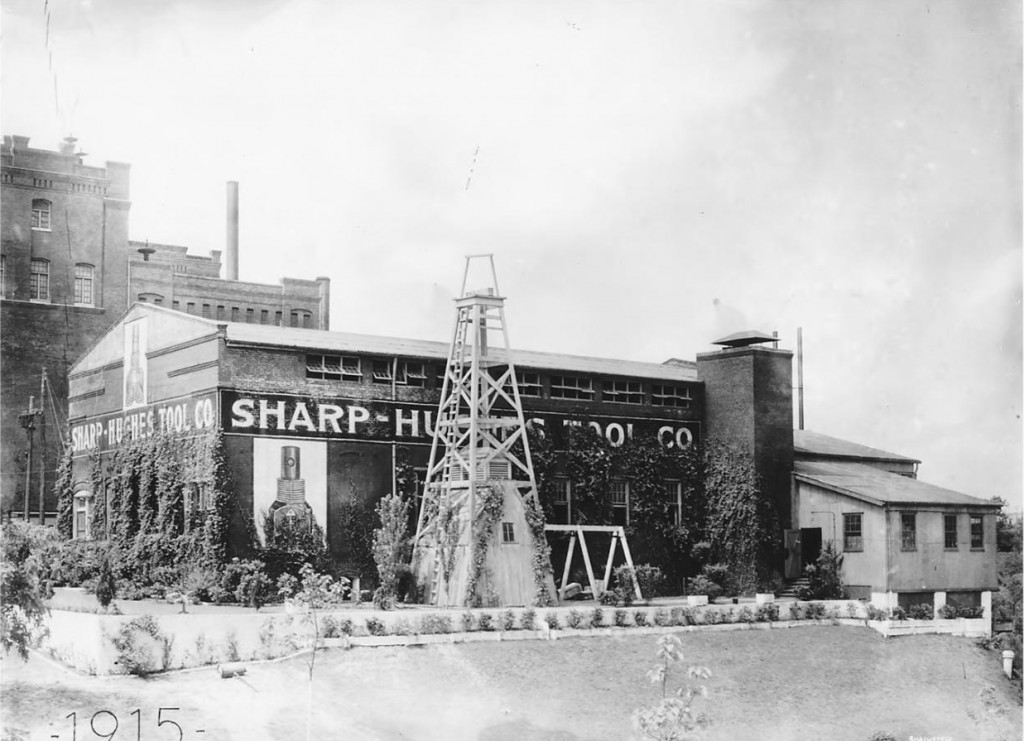

The Houston manufacturing operations of Sharp-Hughes Tool at 2nd and Girard Streets in 1915. The site is on the campus of the University of Houston–Downtown. Photo courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library.

Howard Hughes and Walter Sharp

The Hughes Tool Company began in 1908 as the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company, founded by Walter B. Sharp (1870–1912) and Howard R. Hughes, Sr.

Sharp was an experienced Texas oilfield pioneer who in 1893 drilled for the Gladys City Oil and Gas Manufacturing Company at Beaumont, Texas. The exploratory well on Spindletop Hill did not find oil, but it helped lead to the giant oilfield’s discovery in 1901, according to Texas State Historical Association (TSHA).

In 1896, Sharp was one of the drillers at Corsicana when the state’s first commercial oilfield was developed. While there, he met Joseph “J.S.” Cullinan, who became a lifelong friend. Cullinan in 1902 founded the Texas Company (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

Sharp and Hughes in 1907 drilled test wells at Goose Creek/ “When both wells had to be abandoned because of the hard rock encountered, the two men began to consider the possibility of developing a roller rock bit. It was eventually arranged for Hughes to proceed with the designing and construction of a bit, with capital provided equally by Sharp and Cullinan.

Rotary drilling bits shaped like fishtails became obsolete in 1909 when the two inventors introduced a dual-cone roller bit. They created a bit “designed to enable rotary drilling in harder, deeper formations than was possible with earlier fishtail bits,” according to a Hughes historian. Secret tests took place on a drilling rig at Goose Creek, south of Houston.

Hard Rock at Goose Creek

“In the early morning hours of June 1, 1909, Howard Hughes Sr. packed a secret invention into the trunk of his car and drove off into the Texas plains,” noted Gwen Wright of History Detectives in 2006. The drilling site was near Galveston Bay. Rotary drilling “fishtail ” bits of the time were “nearly worthless when they hit hard rock.”

The new technology would soon bring faster and deeper drilling worldwide, helping to find previously unreachable oil and natural gas reserves. The dual-cone bit also created many Texas millionaires, explained Don Clutterbuck, one of the PBS show’s sources.

“When the Hughes twin-cones hit hard rock, they kept turning, their dozens of sharp teeth (166 on each cone) grinding through the hard stone,” he added.

Although several inventors tried to develop better rotary drill bit technologies, Sharp-Hughes Tool Company was the first to bring it to American oilfields. Drilling times fell dramatically, saving petroleum companies huge amounts of money.

Howard Hughes Sr. (1869 – 1924) on August 10, 1909, was awarded a U.S. patent for a dual-cone drill bit that could crush hard rock.

The Society of Petroleum Engineers has noted that about the same time Hughes developed his bit, Granville A. Humason of Shreveport, Louisiana, patented the first cross-roller rock bit, the forerunner of the Reed cross-roller bit.

Biographers have noted that Hughes met Granville Humason in a Shreveport bar, where Humason sold his roller bit rights to Hughes for $150. The University of Texas Center for American History Collection includes a 1951 recording of Humason talking about that chance meeting. He recalled spending $50 of his sale proceeds at the bar that evening.

After Walter Sharp died in 1912, his widow Estelle Sharp sold her 50 percent share in the company to Hughes. It became Hughes Tool in 1915. Despite legal action between Hughes Tool and the Reed Roller Bit Company in the late 1920s, Hughes prevailed and his oilfield service company prospered.

Hughes Tool

By 1934, Hughes Tool engineers designed and patented the three-cone roller bit, an enduring design that remains much the same today. Hughes’ exclusive patent lasted until 1951, which allowed his Texas company to grow worldwide. More innovations (and mergers) would follow.

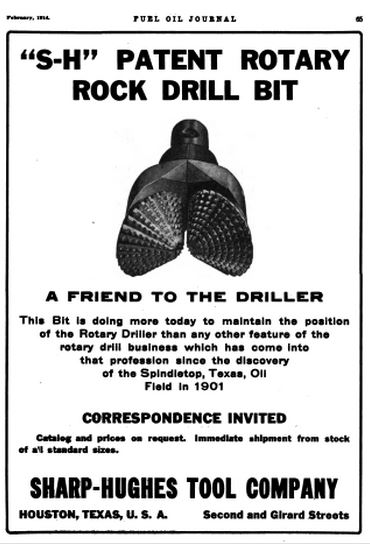

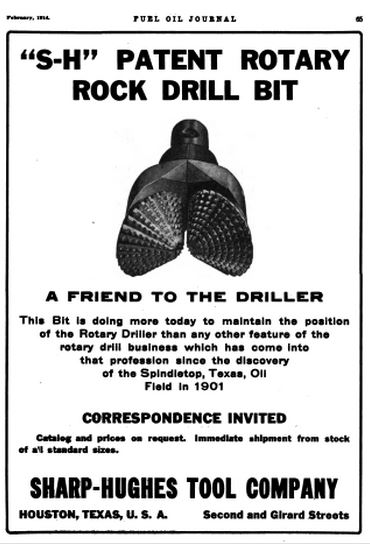

A February 1914 advertisement for the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in Fuel Oil Journal.

Frank Christensen and George Christensen had developed the earliest diamond bit in 1941 and introduced diamond bits to oilfields in 1946, beginning with the Rangley field of Colorado. The long-lasting tungsten carbide tooth came into use in the early 1950s.

After Baker International acquired Hughes Tool Company in 1987, Baker Hughes acquired the Eastman Christensen Company three years later. Eastman was a world leader in directional drilling.

When Howard Hughes Sr. died in 1924, he left three-quarters of his company to Howard Hughes Jr., then a student at Rice University. The younger Hughes added to the success of Hughes Tool while becoming one of the richest men in the world. His many legacies include founding Hughes Aircraft Company and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Learn more in Making Hole – Drilling Technology.

Oilfield Service Competition

A major competitor for any energy service company, today’s Schlumberger Limited can trace its roots to Caen, France. In 1912, brothers Conrad and Marcel began making geophysical measurements that recorded a map of equipotential curves (similar to contour lines on a map). Using very basic equipment, their field experiments led to the invention of a downhole electronic “logging tool” in 1927.

After developing an electrical four-probe surface approach for mineral exploration, the brothers lowered another electric tool into a well. They recorded a single lateral-resistivity curve at fixed points in the well’s borehole and graphically plotted the results against depth – creating first electric well log of geologic formations.

Meanwhile, another service company in Oklahoma, the Reda Pump Company had been founded by Armais Arutunoff, a close friend of Frank Phillips. By 1938, an estimated two percent of all the oil produced in the United States with artificial lift, was lifted by an Arutunoff pump.

Learn more in Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump (also see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Carl Baker and Howard Hughes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/carl-baker-howard-hughes. Last Updated: July 17, 2025. Original Published Date: December 17, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 12, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Founded in 1932, the oilfield service company Lane-Wells developed powerful perforating guns.

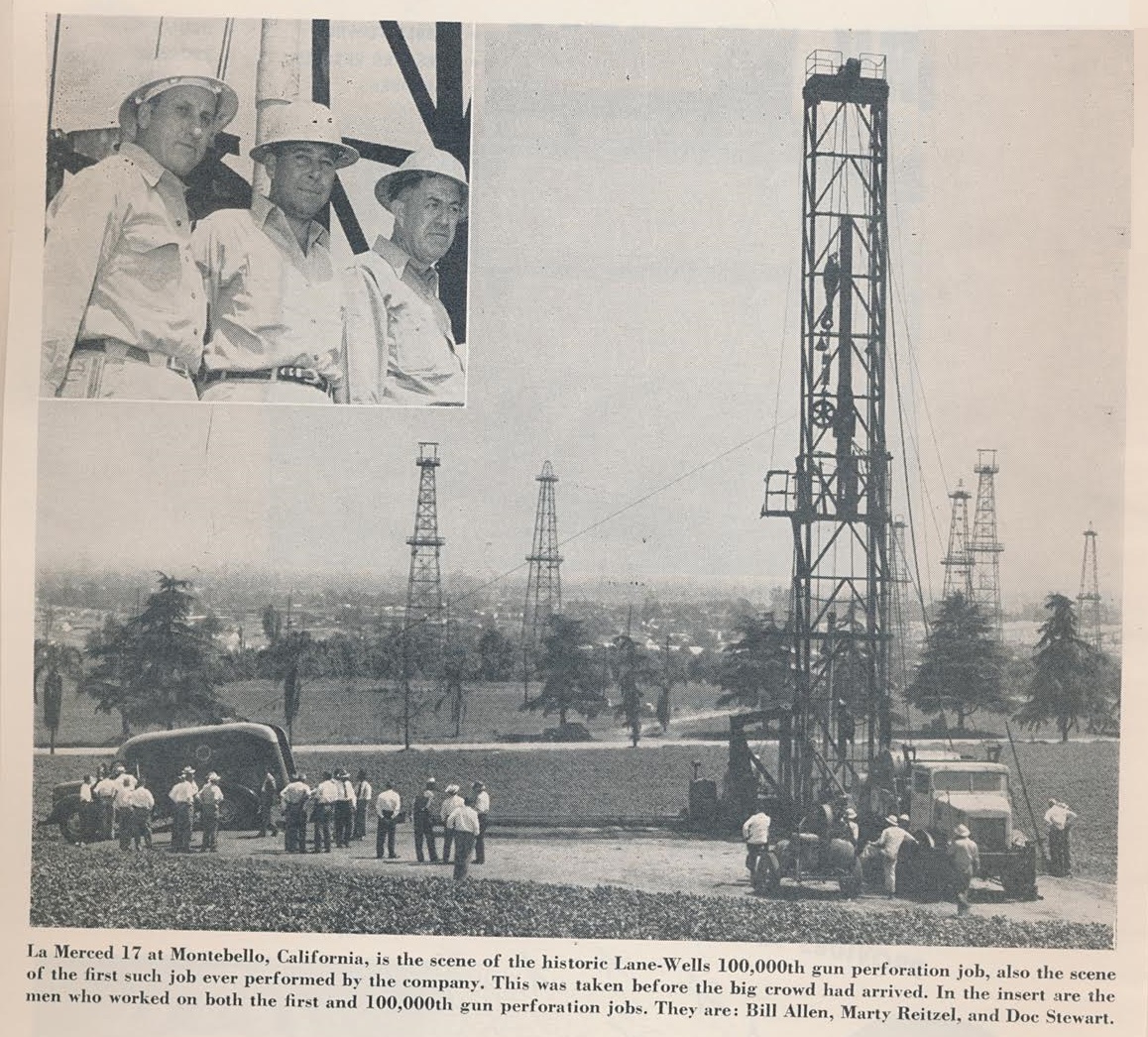

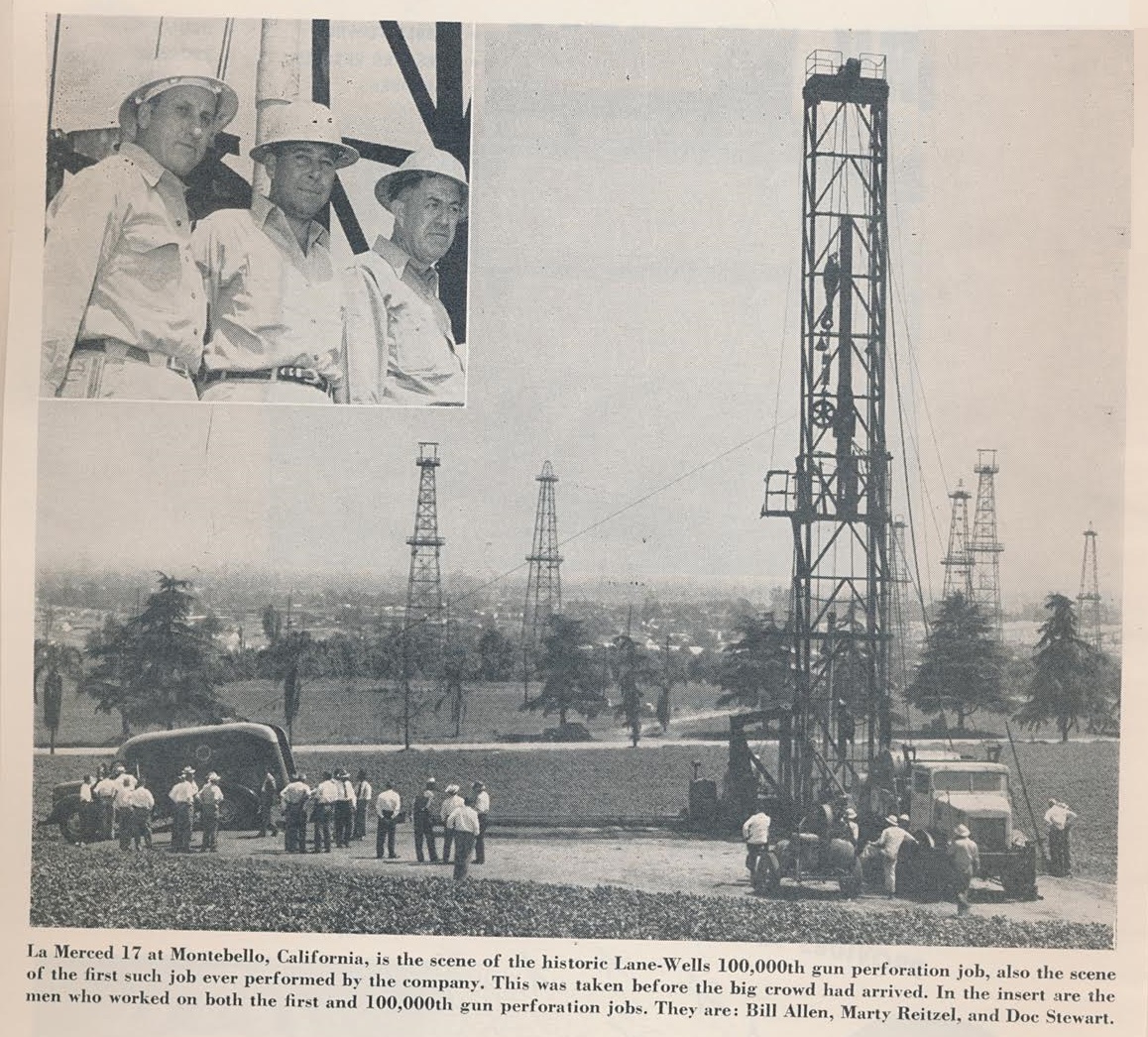

Fifteen years after its first oil well perforation job, Lane-Wells Company returned to the same well near Montebello, California, to perform its 100,000th perforation. The publicity event of June 18, 1948, was a return to Union Oil Company’s La Merced No. 17 well.

The gathering of executives at the historic well celebrated a significant leap in petroleum production technology. The combined inventiveness of the two oilfield service companies had accomplished much in a short time, “so it was a colorful ceremony,” reported a trade magazine.

As production technologies evolved after World War II, Lane-Wells developed a downhole gun with explosive energy to cut through well casing. Above, one of the articles preserved in a family scrapbook, courtesy Connie Jones Pillsbury, Atascadero, California.

Officials from both companies and guests gathered to witness the repeat performance of the company’s early perforating technology, noted Petroleum Engineer in its July 1948 issue. Among them were “several well-known oilmen who had also been present on the first occasion.”

Walter Wells, chairman of the board for Lane-Wells, was present for both events. The article reported he was more anxious at the first, which had been an experiment to test his company’s new perforating gun. In 1930, Wells and another enterprising oilfield tool salesman, Bill Lane, developed a practical way of using guns downhole.

The two men envisioned a tool that could shoot steel bullets through casing and into the formation. They would create a multiple-shot perforator that fired bullets individually by electrical detonation. After many test firings, commercial success came at the Union Oil Company La Merced well.

Cover of a special publication featuring the 75th anniversary of Baker Atlas oil well service company. Lane-Wells became part of Baker Atlas, today a division of Baker-Hughes

Founded in Los Angeles in 1932, the oilfield service company Lane-Wells built a fleet of trucks as it became a specialized provider of well perforations — a key service for enhancing well production (see Downhole Bazooka).

The two men designed tools that would better help the oil industry during the Great Depression. “Bill Lane and Walt Wells worked long hours at a time, establishing their perforating gun business,” explained Susan Wells in a 2007 book celebrating the 75th anniversary of Baker-Atlas.

“It was a period of high drilling costs, and the demand for oil was on the rise,” Wells added. “Making this scenario worse was the fact that the cost of oil was relatively low.”

Shotgun Perforator

By late 1935, Lane-Wells recognized high-powered guns were needed for breaking through casing, cement and into oil-bearing rock formations.

An experienced oilfield worker, Sidney Mims, had patented a similar technical tool for this, but he could not get it working as well as it should. Lane and Wells purchased the patent and refined the downhole gun design. Lane-Wells developed a remotely controlled 128-shot perforator — a downhole shotgun.

“Lane and Wells publicly used the re-engineered shotgun perforator they bought from Mims on Union Oil’s oil well La Merced No. 17,” Wells noted. “There wasn’t any production from this oil well until the shotgun perforator was used, but when used, the well produced more oil than ever before.”

Lane-Wells provided perforating services using downhole “bullet guns,” seen here in 1940.

The successful application attracted many other oil companies to Lane-Wells as the company modified the original 128-shot perforator to use 6-shot and 10-shot cylinders. For a public relations event, executives decided to conduct the company’s 100,000th perforation almost 16 years after the first at the La Merced No. 17 well.

Continued success in Oklahoma and Texas oilfields led to new partnerships beginning in the 1950s. A Lane-Wells merger with Dresser Industries was finalized in March 1956, and another corporate merger arrived in 1968 with Pan Geo Atlas Corporation, forming the service industry giant Dresser Atlas.

A 1987 joint venture with Litton Industries led to Western Atlas International, which became an independent company before becoming a division of Baker-Hughes in 1998 (Baker Atlas) providing well logging and perforating services. Dresser merged with Halliburton the same year.

Preserving Oil History

Connie Jones Pillsbury of Atascadero, California, and the family of Walter T. Wells wanted to preserve rare Lane-Wells artifacts. She contacted the American Oil & Gas Historical Society for help finding a home for an original commemorative album, press clippings and guest book from June 18, 1948.

Seeking to preserve the “Lane-Wells 100,000th Gun Perforating Job” event at Montebello, California — site of the Union Oil Company La Merced No. 17 well — Pillsbury and the children of Dale G. Jones, the grandson of Walter T. Wells, contacted petroleum museums, libraries, and archives (also see Oil & Gas Families).

Pillsbury’s quest to preserve the Walter T. Wells album and records proved successful, and she emailed AOGHS to report the family’s album was “safely archived at the USC Libraries Special Collections. Sue Luftschein is the Librarian. It’s on Online Archive of California (OAC).”

The Lane-Wells West Coast headquarters designed by architect William E. Mayer and completed in 1937 in what became Huntington Park in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Water and Power Associates.

The Lane-Wells collection — Gift of Connie Pillsbury, October 27, 2017 — can be accessed via the OAC website.

Title: Lane-Wells Company records

Creators: Wells, Walter T. and Lane-Wells Company

Identifier/Call Number: 7055

Physical Description: 1.5 Linear Feet 1 box

Date (inclusive): 1939-1954

The archive abstract also notes:

“This small collection consists of a commemorative album celebrating the 100,000th Gun Perforating Job by the Lane-Wells Company of Los Angeles on June 18, 1948, and additional printed ephemera, 1939-1954, created and collected by Walter T. Wells, co-founder and Chairman of the Board of the Lane-Wells Company.”

Pillsbury sought a museum or archive home for her rare oil patch artifact, which came from an event attended by many from the Los Angeles petroleum industry.

“The professionally-prepared book has all of the attendees signatures, photographs and articles on the event from TIME, The Oil and Gas Journal, Fortnight, Oil Reporter, Drilling, The Petroleum Engineer, Oil, Petroleum World, California Oil World, Lane-Wells Magazine, the L.A. Examiner, L.A. Daily News and L.A. Times, etc.,” Pillsbury noted in 2017.

The 1948 commemorative book, now preserved at USC, “was given to my first husband, Dale G. Jones, Ph.D., grandson of Walter T. Wells, one of the founders of Lane-Wells,” she added. “His children asked me to help find a suitable home for this book. I found you (the AOGHS website) through googling ‘History of Lane-Wells Company.’”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: 75 Years Young…BAKER-ATLAS The Future has Never Looked Brighter (2007); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields

(2007); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields (1990)

(1990) . Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

. Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lane-Wells 100,000th Perforation” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/oil-well-perforation-company. Last Updated: June 12, 2025. Original Published Date: June 30, 2017.