by Bruce Wells | Jun 4, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

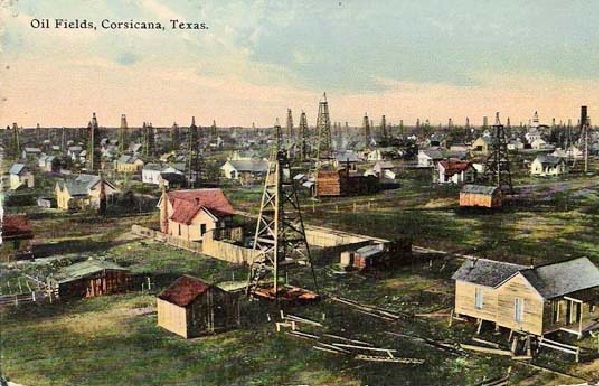

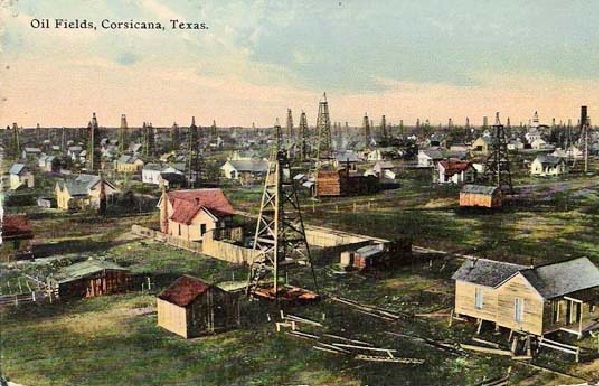

Drilling for water in 1894, Corsicana discovered an oilfield and became the richest town in Texas.

In the summer of 1894, town leaders of Corsicana, Texas, hired a contractor to drill a water well on 12th Street. The driller found oil instead. The small community’s oilfield discovery launched the first Texas oil boom seven years before a more famous gusher at Spindletop Hill far to the southeast.

Corsicana’s first oil well produced less than three barrels of oil a day, but it quickly transformed the sleepy agricultural town into a petroleum and industrial center. The discovery launched industries, including service companies and manufacturers of the newly invented rotary drilling rig.

The first Texas oil boom arrived in 1894 with discovery of the Corsicana oilfield by a drilling contractor hired by the city to find water. An annual Derrick Day Chili & BBQ Cook-Off celebrates the discovery. Colorized postcard of Navarro County oil wells, circa 1910.

Corsicana local historians consider the 1894 discovery well, drilled on South 12th Street, the first significant commercial oil discovery west of the Mississippi (Kansans claim the same distinction for an 1892 Neodesha oil well).

Early Texas Oilfields

The American Well and Prospecting Company (from Kansas) made the oil strike on June 9, 1894, at a depth of 1,035 feet. The city council — angry and still wanting water for its growing community 55 miles south of Dallas — paid only half of the drilling contractor’s $1,000 fee. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 13, 2024 | Petroleum Technology

“Small cannons throwing a three-inch solid shot are kept at various stations throughout the region…”

Early petroleum technologies included cannons for fighting oil tank storage fires, especially in the Great Plains where lightning strikes ignited derricks, engine houses and tanks. Shooting a cannon ball into the base of a burning storage tank allowed oil to drain into a holding pit or ditch, putting out the fire.

“Oil Fires, like battles, are fought by artillery,” proclaimed the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in December 1884. Oilfield conflagrations had challenged America’s petroleum industry since the first commercial well in 1859 (see First Oil Well Fire). An MIT student offered a recent, first-person account.

Especially in mid-west oilfields, lightning strikes could ignite derricks, engine houses, and rows of storage tanks. Photo courtesy Butler County History Center & Kansas Oil Museum.

“Lightning had struck the derrick, followed pipe connections into a nearby tank and ignited natural gas, which rises from freshly produced oil. Immediately following this blinding flash, the black smoke began to roll out,” the writer noted in The Tech, a student newspaper established in 1881.

The MIT article, “A Thunder Storm in the Oil Country,” described what happened next:

“Without stopping to watch the burning tank-house and derrick, we followed the oil to see where it would go. By some mischance the mouth of the ravine had been blocked up and the stream turned abruptly and spread out over the alluvial plain,” reported the article.

Oilfield operators used muzzle-loading cannons to fired solid shot at the base of burning oil tanks, draining the oil into ditches to extinguish the blaze.

“Here, on a large smooth farm, were six iron storage tanks, about 80 feet in diameter and 25 feet high, each holding 30,000 barrels of oil,” it added, noting the burning oil “spread with fearful rapidity over the level surface” before reaching an oil storage tank.

“Suddenly, with loud explosion, the heavy plank and iron cover of the tank was thrown into the air, and thick smoke rolled out,” the writer observed.

“Already the news of the fire had been telegraphed to the central office and all its available men and teams in the neighborhood ordered to the scene,” he added. “The tanks, now heated on the outside as well as inside, foamed and bubbled like an enormous retort, every ejection only serving to increase the heat.”

Technological innovations in Oklahoma oilfields helped improve petroleum production worldwide. The oilfield artillery exhibit at the Oklahoma Oil Museum in Seminole educated visitors until the museum closed in 2019. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The area of the fire rapidly extended to two more tanks: “These tanks, surrounded by fire, in turn boiled and foamed, and the heat, even at a distance, was so intense that the workmen could not approach near enough to dig ditches between the remaining tanks and the fire.”

Noting the arrival of “the long looked for cannon,” the reporter noted, adding, “since the great destruction is caused by the oil becoming overheated, foaming and being projected to a distance, it is usually desirable to let it out of the tank to burn on the ground in thin layers; so small cannons throwing a three-inch solid shot are kept at various stations throughout the region for this purpose.”

The wheeled cannon was placed in position and “aimed at points below the supposed level of the oil and fired,” explained the witness. “The marksmanship at first was not very good, and as many shots glanced off the iron plates as penetrated, but after a while nearly every report was followed by an outburst.”

The oil in three storage tanks was slowly drawn down by this means, “and did not again foam over the top, and the supply to the river being thus cut off the fire then soon died away.”

A cannon from the Magnolia Petroleum tank farm was donated to the city of Corsicana, Texas, by Mobil Oil Company in 1969.

In the end, “it was not till the sixth day from that on which we saw the first tank ignited that the columns of flame and smoke disappeared. During this time 180,000 barrels of crude oil had been consumed, besides the six tanks, costing $10,000 each, destroyed,” concluded the 1884 MIT article.

Visitors to Corsicana, Texas — where oil was discovered while drilling for water in 1894 (see First Texas Oil Boom) — can view an oilfield cannon donated to the city in 1969 by Mobil Oil. The marker notes:

“Fires were a major concern of oil fields. This cannon stood at the Magnolia Petroleum tank farm in Corsicana. It was used to shoot a hole in the bottom of the Cyprus tanks if lightning struck. The oil would drain into a pit around the tank to be pumped away. The cannon was donated by Mobil Oil Company in 1969.”

Another cannon can be found on exhibit in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, near the first Oklahoma oil well, drilled a decade before 1907 statehood. Exhibits at Discovery One Park include an 84-foot cable-tool derrick first erected in 1948 and replaced in 2008.

Oilfield artillery also can be found at the Kansas Oil Museum in Butler County.

An oilfield cannon exhibit in Discovery One Park, the Bartlesville site of the first significant Oklahoma oilfield discovery of 1897. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Another educated tourists in Ohio. The Wood County Historical Center and Museum in Bowling Green displays its own “unusual fire extinguisher” among its collection. The Buckeye Pipeline Company of Norwood donated the cannon, according to the museum’s Kelli King.

“The cannon, cast in North Baltimore (Ohio), was used in the 1920s in Cygnet before being moved to Northwood,” Kelli says, adding that more local history can be found in the museum’s documentary “Ohio Crude” and in its exhibit, “Wood County in Motion.” Museums in nearby Hancock County and Allen County also have interesting petroleum collections.

Modern Oilfield Fire Fighting

When oilfield well control expert and firefighter Paul “Red” Adair died at age 89 in 2004, he left behind a famous “Hell Fighter” legacy. The son of a blacksmith, Adair was born in 1915 in Houston and served with a U.S. Army bomb disposal unit during World War II.

Adair began his career working for Myron M. Kinley, who patented a technology for using charges of high explosives to snuff out well fires. Kinley, whose father had been an oil well shooter in California in the early 1900s, also mentored Asger “Boots” Hansen and “Coots” Mathews of Boots & Coots International Well Control and other firefighters.

Famed oilfield firefighter Paul “Red” Adair of Houston, Texas, in 1964.

In 1959, Adair founded Red Adair Company in Houston and soon developed innovative techniques for “wild well” control. His company would put out more than 2,000 well fires and blowouts worldwide — onshore and offshore.

The Texas firefighter’s skills were tested in 1991 when Adair and his company extinguished 117 oil well fires set in Kuwait by Saddam Hussein’s retreating Iraqi army. Adair was joined by other pioneering well firefighting companies, including Cudd Well Control, founded by Bobby Joe Cudd in 1977.

Russian Anti-Tank Gun

Unable to control a 2020 oil well fire in Siberia, a Russian oil company called in the army. In May, a well operated by the Irkutsk Oil Company in Russia’s Irkutsk region ignited into a geyser of flame. When Irkutsk Oil Company firefighters were unable to extinguish the blaze, the Russian Defense Ministry flew a Rapira MT-12 an anti-tank gun to the well site.

The Russian army’s 100-millimeter gun repeatedly fired at the flaming wellhead, “breaking it from the well and allowing crews to seal the well,” according to a June 8, 2020, article in Popular Mechanics.

In 1966, the Soviet Union used a nuclear device to extinguish a natural gas fire — as U.S. scientists experimented with nuclear fracturing of natural gas wells (see Project Gasbuggy tests Nuclear “Fracking”).

Learn more about the earliest oilfield fires and how the petroleum industry fought them with cannons, wind-making machines (including jet engines), and nuclear bombs in Oilfield Firefighting Technologies.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfield Artillery fights Fires.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/oilfield-artillery-fights-fires. Last Updated: December 12, 2024. Original Published Date: September 1, 2005.