by Bruce Wells | May 15, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Widely publicized drilling booms attracted investors seeking “black gold” riches — real or imagined.

Exaggerated, questionable, and sometimes fraudulent claims by shady business ventures seeking investors grew in the years following World War I. As the Great Depression approached, many states passed “blue sky laws” to regulate securities sales and protect the public from fraud.

It would take an act of Congress in 1934 to stop skilled business hucksters from taking advantage of unwary investors seeking often fictional profits. Federal lawmakers established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to help rein in exaggerated claims found in newspaper advertisements, mail solicitations, and other stock promotions.

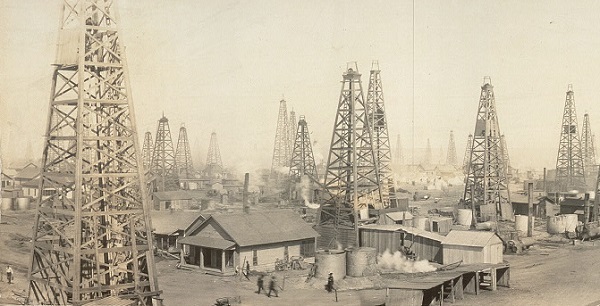

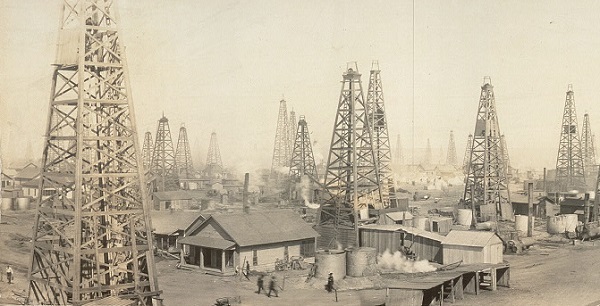

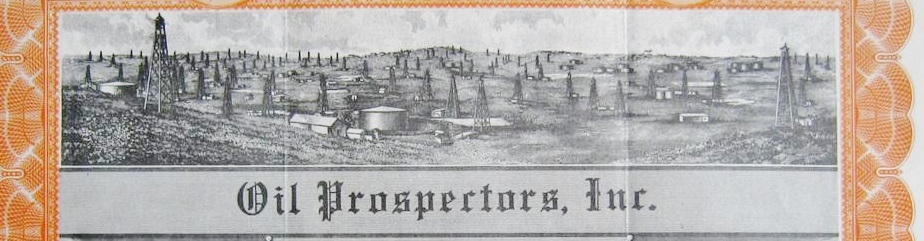

Widely publicized giant oilfield discoveries at Burkburnett, Texas, in 1918 (above) and nearby “Roaring Ranger” one year earlier led to many inexperienced exploration ventures and exaggerated promotions. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Since the U.S. petroleum industry’s earliest booms and busts in Pennsylvania following the Civil War, the need for dependable information and early financial centers — petroleum exchanges — led to a new profession — the oil scout.

As demand for refined kerosene for lamps grew, the search for new oilfields moved to mid-continent. Thousands of exploration and production companies were established. Most drilled dry holes. When wildcat wells (remote) revealed giant oil and natural fields in Texas and Oklahoma, a new generation of business financing hucksters took advantage.

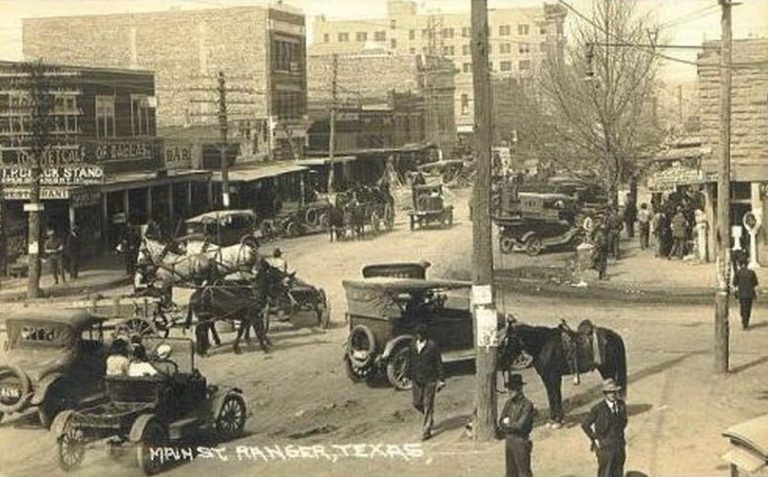

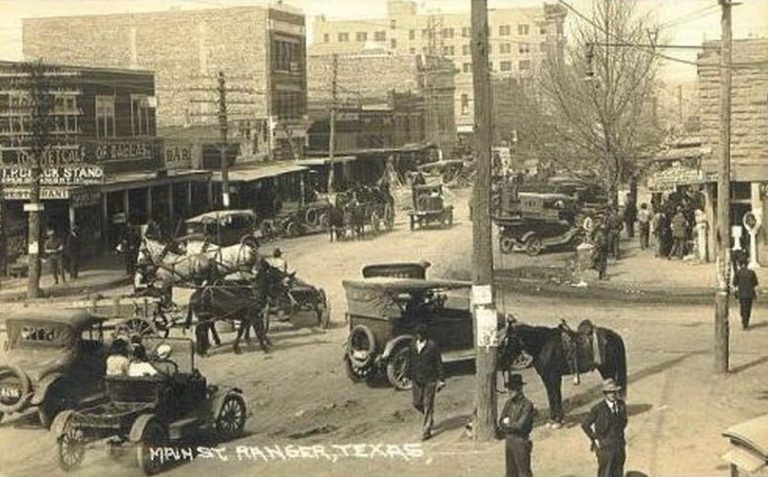

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a massive oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Giant oilfield discoveries in North Texas made headlines, leading to the hundreds of new exploration companies (see Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?). Many began by seeking capital from local investors, often banks, doctors, and civic leaders. Financial swindlers saw opportunities to take advantage of oilfield discoveries and the resulting oil fever.

Newspapers nationwide reported wells with geysers of oil at Electra (1911), Ranger (1917), and the “World’s Wonder Oilfield” of Boom Town Burkburnett (1918). Publicity about these oil booms rekindled enthusiasm for Texas petroleum riches not seen since the giant oilfield discovery at Spindletop Hill in 1901, the famous “Lucas Gusher.”

Sudden, unexpected “black gold” or “Texas tea” wealth brought prosperity to struggling farming communities. Thanks to the Ranger oilfield, Eastland County’s Merriman Baptist Church (and graveyard) was once declared the richest church in America.

Black Gold Dreams

Criminals specializing in financial deception joined the influx of drilling contractors, workers, equipment suppliers, lease brokers, and associated oilfield service companies. In part to combat fraud in North Texas, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), founded in 1917, American Petroleum Institute (API), founded in 1919, and other industry associations organized.

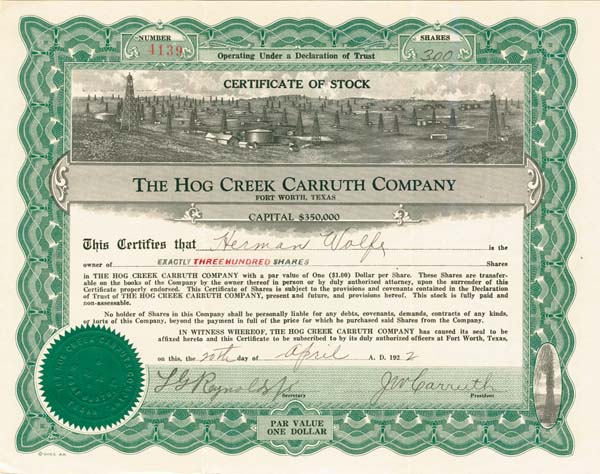

With so many oil boom-inspired companies forming so quickly, the rapid printing of eye-catching but boiler-plate stock certificates often occurred (see Oil Prospects Inc. for one of the most common certificate vignettes).

In a rush to find investors, quickly formed exploration companies ended up using the same oilfield scene for stock certificates. It might have saved time and money by choosing a printer’s common vignette.

Already iconic U.S. boom towns and busts (see the remarkable 1865 rise and fall of Pithole, Pennsylvania) would help launch major companies like Marathon and Texaco, as did the first California oil wells. New petroleum discoveries attracted experienced companies — and many more inexperienced exploration and production ventures that aggressively sought leases, equipment and men, and investors.

However, with little knowledge of the new science of petroleum geology and drilling technologies, few of newly formed companies would find oil. Most did not survive long in the highly competitive oilfields.

Crowding too many wells on leases and a lack of infrastructure for storing and transporting oil harmed the environment. Many companies learned from hard experience, but more went bankrupt without ever finding oil.

Competing exploration companies, lacking petroleum engineers and efficient production technologies, often overproduced geological formations. Unchecked drilling and oversupply in the oil market led prices to collapse as low as 15 cents per 42-gallon oil barrel in the giant East Texas oilfield of the 1930s.

Huckster of Hog Creek

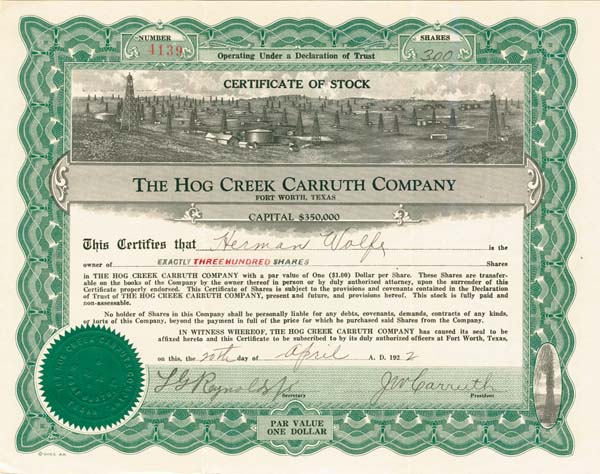

The lure black gold also attracted skilled confidence men who could create oil companies on paper. J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth was among the most notorious.

Financial World in 1912 described “Hog Creek” Carruth as a con man who made a fortune selling worthless oil stocks. The magazine also cited the far better known infamous explorer Dr. Frederick Cook (learn more in Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter).

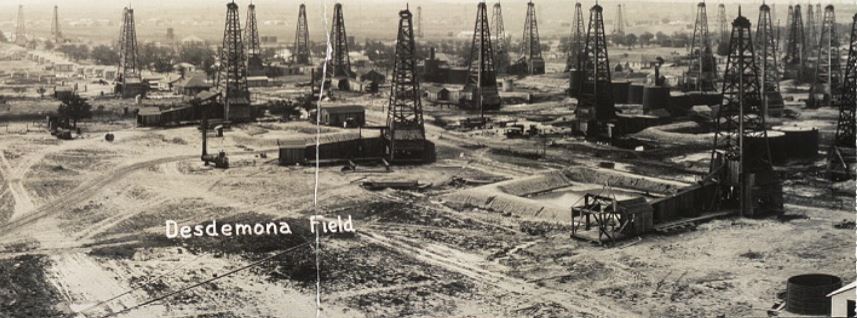

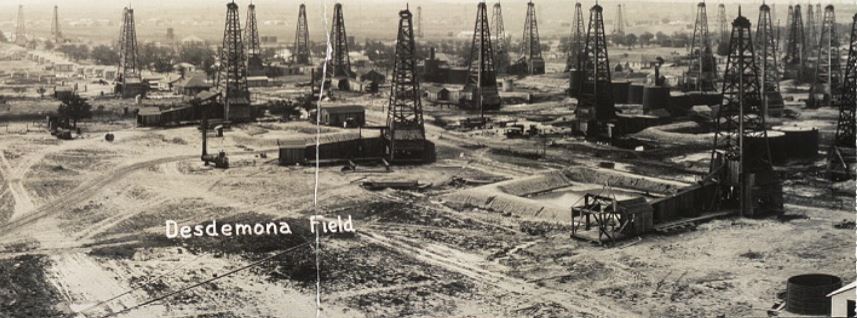

In September 1918 a discovery well near Desdemona blew in after reaching a depth of 2,960 feet, initially producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day. “Unlike Ranger, Desdemona was a small operator’s field. Production reached a peak of 7,375,825 barrels in 1919, and then dropped sharply, chiefly because of over drilling,” according to the Handbook of Texas Online.

“Hog Creek” Carruth proclaimed himself to be the discoverer of the Desdemona oilfield (he was not). He advertised expansively to sell worthless stocks inflated by his phony reputation.

Pilgrim Oil Company

Pilgrim Oil Company formed as a common law trust estate (unincorporated business managed by trustees) in Fort Worth, Texas, on December 20, 1920. The company’s trustees included George M. Richardson and Warren H. Hollister. and was capitalized at $1 million with 100,000 shares offered at par value of $10.

The petroleum company, another fraudulent enterprise of J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth, would be his last.

J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth falsely claimed to have discovered the Desdemona, oilfield, along Hogg Creek. Detail from circa 1919 panoramic photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The oilfield along Hog Creek had been discovered in 1918, just one year after the famous Ranger well. This new field at Desdemona (once called Hog Town) attracted the usual rush of new exploration companies, many with little or no drilling experience.

Among the Eastland County startups, a wily financial conman’s Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company profited by colorful stock sale advertisements to attract investors.

The skillfully exaggerated promotions of Carruth prompted one contemporary writer to admire the crook’s audacity. “Any reader who cannot get a thrill out of Carruth’s highly colored advertising literature is indeed phlegmatic,” the observer declared.

But harm to many small, unwary investors was real. Most of the stock sales’ dollars went into Carruth’s pockets instead of his companies. Even the failure of his oil companies became part of his schemes.

Hogg Oil + Hog Creek Carruth Oil

Carruth merged two of his insolvent petroleum companies — Hogg Oil Company and Hogg Creek Carruth Oil Company — to create the Pilgrim Oil Company. His latest venture attracted some skeptical attention from financial magazine editors. The Pilgrim Oil Company, “makes a business of gathering in defunct oil companies,” reported Financial World.

As part of his connived merger game plan, stockholders of the two bankrupt Carruth oil ventures had to buy an additional 25 percent of Pilgrim Oil Company shares (in cash) or lose their investments entirely. Carruth used this money to pay dividends, thereby luring more buyers into his petroleum company Ponzi scheme.

Financial World noted, “This is a promoter’s way of reloading old stockholders with additional $25 worth of stock for every $100 they hold in a defunct company.”

J.W. Carruth merged his fraudulent Hogg Creek Carruth Oil with his other fraudulent oil company to create Pilgrim Oil company, a Ponzi scheme using investors’ purchase money to pay dividends and lure more buyers.

In 1923, a federal court indicted J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth for mail fraud. Also indicted were Pilgrim Oil Company trustees Richardson and Hollister. Eighty-nine other shady characters also were named in a sweeping indictment aimed at stock hucksters.

U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth

Federal prosecutors reviewed financial harm to innocent Pilgrim Oil Company shareholders, who pleaded to the court for justice.

“False, fraudulent, and untrue representations were made for the purpose of inducing plaintiffs to buy the said stock of the said two companies, and for the purpose of cheating, swindling, and defrauding plaintiffs out of their money, and did cheat, swindle, and defraud plaintiffs out of their said money,” the attorneys declared.

“That in 1922, and for a long time prior and subsequent thereto, defendant was engaged in handling and selling oil stock certificates and owned and controlled interests in various oil companies and concerns in this state,” the prosecutors added. Dozens of convictions followed.

Carruth earned a one-year sentence in Leavenworth, Kansas. He joined the federal penitentiary’s oil-scheme alumni Dr. Frederick Cook, the fraudulent Arctic explorer turned oil well promoter. Pilgrim Oil Company and the other Carruth company shareholders were left with stock certificates of no value, except perhaps as a family stories and heirlooms.

Convicted felon “Hog Creek” Carruth, who died in obscurity in 1932, should not be confused with former Texas Governor James S. “Big Jim” Hogg, who helped discover the important West Columbia oilfield in 1917 — learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells.

New Jersey Oilfield?

A West Coast newspaper in 1916 reported on a rare attempt to find an East Coast oilfield. “Lewis Steelman, the man who has been prospecting for oil near Millville, N.J., for some time, has begun active work to locate an oil well and he confidently expects to strike the fluid,” reported California’s Santa Ana Register.

In New Jersey, the recently established Steelman Realty Gas & Oil Company was selling stock buttressed by the declarations of Dr. H. J. von Hagen, who company executives cited as “one of the world’s greatest living geologists and petroleum engineers.” Learn more in Fake New Jersey Oil Well.

More articles about U.S. exploration and production companies and links for further research can be found in Oil Stock Certificates.

_______________________

Recommended Reading (October 9): The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS annual supporter. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pilgrim-oil-company-exploiting-oil-fever. Last Updated: May 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 9, 2021.

.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 26, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

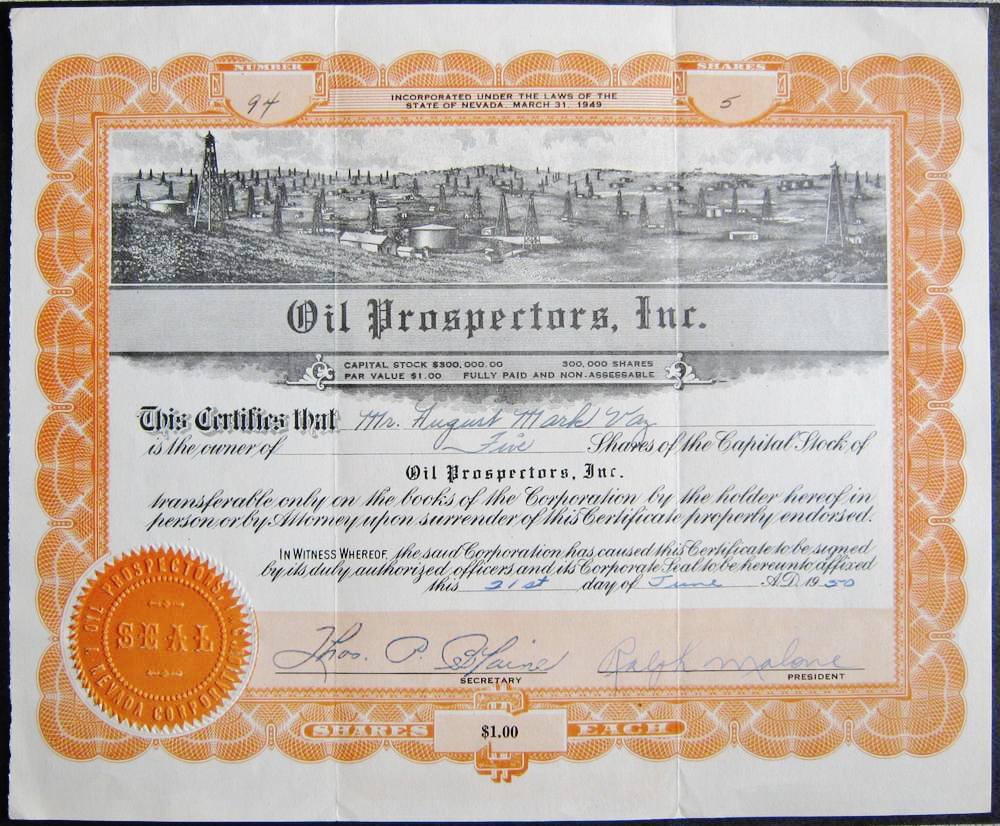

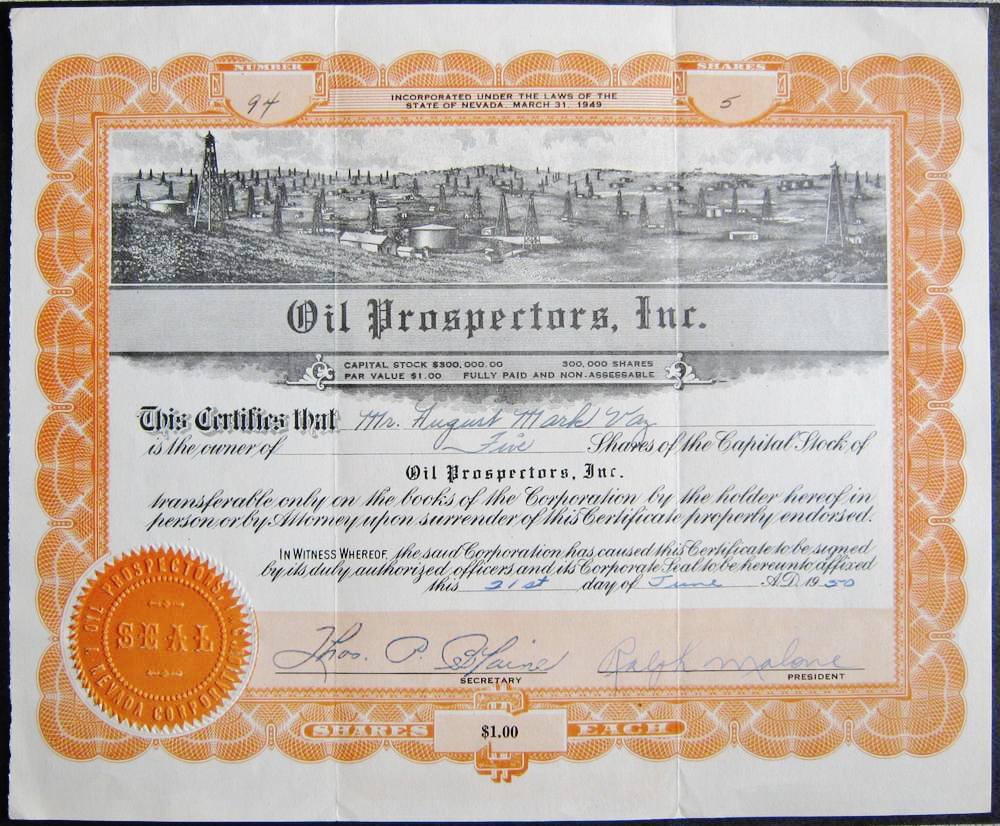

Although geologists, petroleum engineers and other earth scientists were far more helpful for finding “black gold,” Oil Prospectors Inc. preferred unscientific methods to sway unwary investors.

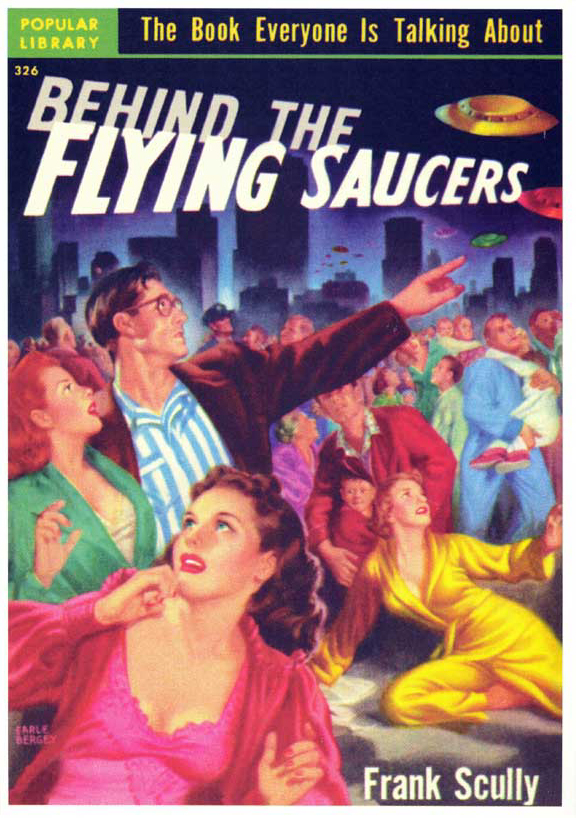

During the Great Depression, some fortune seekers were convinced a “divining rod, a doodlebug, a switch, or a twig” could find oilfields. In the 1950s, others invested in doodlebug technology they were told came from flying saucers. Then as now, any “miraculous machine” could help fleece the gullible.

In the rush to print stock certificates during drilling booms, many companies printed certificates with a field of derricks vignette — often using the same artwork.

Not long after the December 1931 discovery of the Conroe, Texas, oilfield, a “doodlebug” device swindled Houston oil investors out of $20,000. It also sent Ralph Malone and Vivian Buie to jail in 1935.

During their trial in district court, a prosecution witness told of receiving letters describing the doodlebugger as capable of finding oil and natural gas in Polk County.

Malone and Buie claimed their device would find “another field like the Conroe field” worth millions of dollars. They described their doodlebug as “a wonderful instrument that could locate oil pools.”

Learn about Conroe’s oilfield in Technology and the “Conroe Crater.”

Despite their defense attorneys efforts, Malone and Buie (the alleged “brains” of the doodlebug scam), were convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to terms in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Then their defense attorneys were indicted as well.

While their former clients headed off to prison, Arthur Heemann and C. Ray Smith hired their own legal council. The new defense team asserted the accused, “merely were attorneys for the swindlers and did not participate in the scheme.”

It did not help that attorney Heemann had been charged five years earlier with the same crime while promoting the similarly fraudulent Oil Investors Company.

Nonetheless, the lawyers got the lawyers off when the judge ruled them not guilty on April 15, 1938. Two months later, Ralph Malone was transported from Leavenworth to a Tucson, Arizona, prison to finish his three-year sentence.

Doodlebugs, Magnetic Loggers, and Flying Saucers

Although Malone was absent from oil stock scams for several years, investors did not abandon their fascination with doodlebugs. The convicted con man resurfaced in the early 1950s when his penchant for mail fraud landed him in trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

“Often investigation is directed to highly objectionable sales literature which greatly over emphasize the possibilities of success from the proposed security purchase,” the SEC noted in its 17th annual report. “So it was in the case of Oil Prospectors, Inc. and Ralph Malone.”

One year later, the SEC again addressed the issue of doodlebugs, explaining the necessity of resorting to the courts to get compliance with the Securities Act.

“A substantial number of cases requiring injunctive action are those relating to oil and mining promotions,” noted the June 30, 1952, annual report. “The ‘gold brick’ aspect of many of these promotions has by now become quite stereotyped.” The SEC’s complaints seeking injunctions pointed out that, “sellers were omitting to disclose that these individuals had criminal records.”

The commission cited another example of “the almost perennial doodlebug” where the “defendants used in their operations a device called a ‘Magnetic Logger’ and the claims made for its efficacy in discovering oil were the usual ones and were false…There is reason to believe that the injunction obtained by the commission saved the investing public a substantial sum.”

An SEC injunction in 1951 finally brought an end to Oil Prospectors and Ralph Malone disappeared from the news. Doodlebug hoaxes continued.

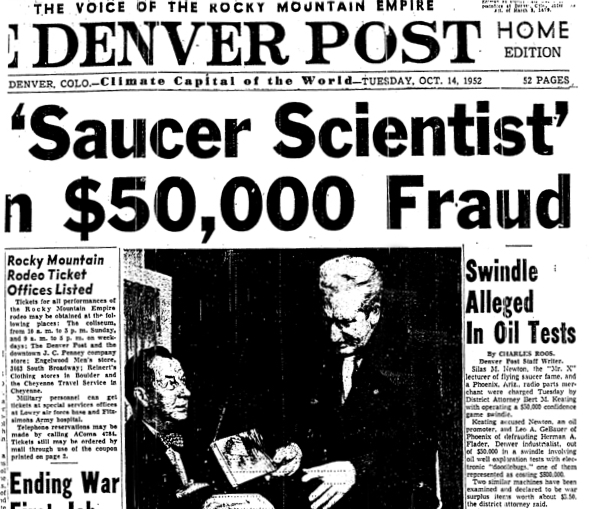

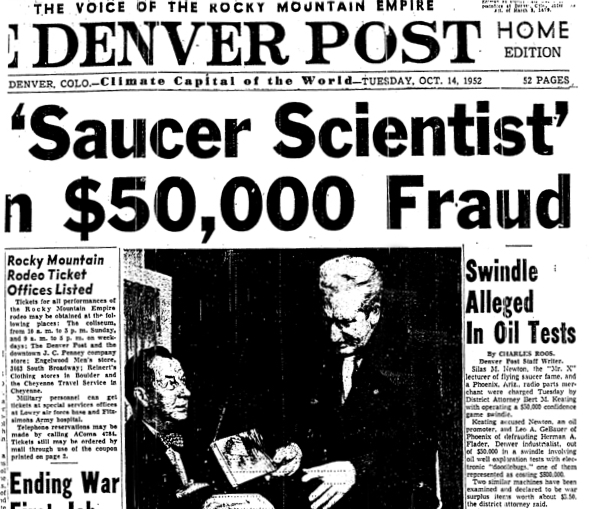

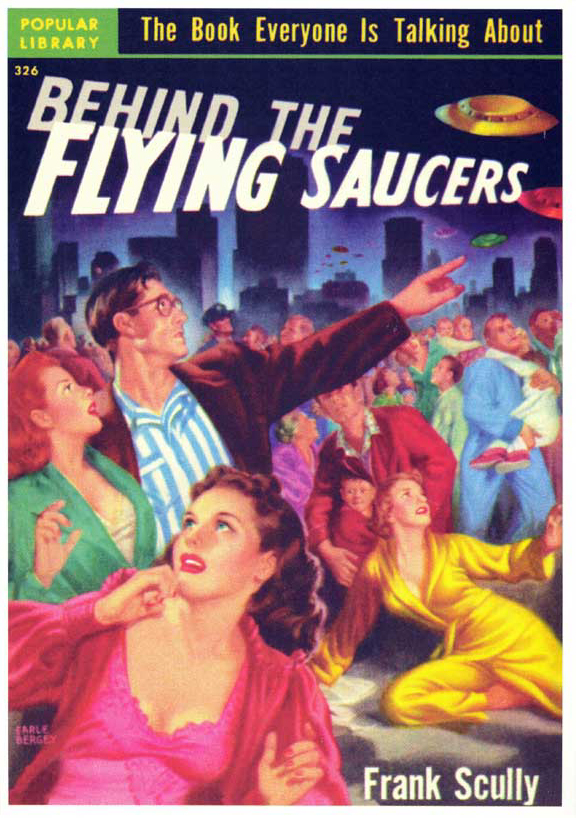

Most notably, Silas Newton and Leo GeBauer, claimed their doodlebug machine “operated on the same magnetic principles as the flying saucers.” The $800,000 contraption had been developed secretly by the government.

They promoted the tale of a 1948 flying saucer crash site near Aztec, New Mexico, that had yielded 16 humanoid bodies (Roswell’s aliens had reportedly arrived a year earlier).

Newton and GeBauer claimed the Aztec crash site included revolutionary technology for finding oil.

Silas Newton and Leo “Dr. Gee” GeBauer convinced author Frank Scully (at right) the government was hiding UFO crash sites and humanoid corpses. Investors believed their claims that a secret alien device could locate vast petroleum reserves.

Although some still maintain an elaborate government cover-up has concealed the real Aztec UFO story, the petroleum exploration technology has received little mention. By 1952, the terrestrial luck of Newton and GeBauer ran out. The Denver Post’s October 14 headline proclaimed, “Saucer Scientist in $50,000 Fraud.”

In 1950 Frank Scully had published Behind Flying Saucers, a book reporting crashed UFOs (powered on magnetic principles) and the discovery of dead extraterrestrial beings.

In September 1952, True Magazine investigated Frank Scully, Silas Newton, and Leo GeBauer, the three principals involved in Scully’s best-selling book, Behind the Flying Saucers.

In 1952 and again in 1956, True magazine published articles that exposed doodlebug machine promoters Silas Newton and “Dr. Gee” (identified as Leo GeBauer) as “oil con artists who had hoaxed a gullible Scully,” according to the 1998 book, UFOs & Alien Contact: Two Centuries of Mystery.

It turned out the UFO inspired oil doodlebug was just a box covered in dials and switches made from $3.50 in surplus radio parts. The revelation brought little comfort to swindled investors.

Stock Certificate Derricks

Speculating in oil stocks has been hazardous since the first company incorporated in 1854 in Pennsylvania (see First American Oil Well). As drilling booms moved westward, thousands of exploration companies competed to exploit “black gold.” Most failed after a few expensive dry holes — or without drilling a single well.

Especially during the major oilfield discoveries beginning after World War I and continuing through the Great Depression, the rush to form oil companies led to certificates that looked remarkably alike. Printing boiler-plate stock certificates was not uncommon in the scramble to find investors.

For example, many short-lived companies’ stocks features the same artwork as Oil Prospectors Inc. Here are just a few:

Buck Run Oil and Refining

Buffalo-Texas Oil

Craven Oil and Refining

Evangeline Oil

Hog Creek Carruth Company

Texas Production Company

Modern Doodlebuggers

The Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG) published its first journal, Geophysics, in 1936. It included articles about the petroleum industry’s three major prospecting methods then used – seismic, gravity, and magnetic. All were based on the scientific method.

The journal’s lead article warned young geophysicists about employing “black magic” or “doodle-bug” methods based on unproven properties of oil, minerals or geological formations. “This is the first time that the term ‘doodle-bug’ was applied to scientific methods, particularly if they had no scientific validity, according to the 1982 book, Geophysics in the Affairs of Men.

“Twenty years later, it was a badge of honor to be known as a doodlebugger, i.e., the field personnel of geophysical crews,” noted the authors Charles C. Bates, T. F. Gaskell and R. B. Rice. “Still later, the term was applied to everyone who worked in exploration geophysics.”

A bronze statue, “The Doodlebugger,” welcomes visitors to the Society of Exploration Geophysicists headquarters in Tulsa. The name is a badge of honor for geophysical crews seeking oil. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Editor’s Note – The sculptor of the SEG statue, Jay O´Meilia of Tulsa, Oklahoma, also was the artist who created two “Oil Patch Warrior” statues – one in Ardmore and another across the Atlantic. See Roughnecks of Sherwood Forest.

More research and articles about U.S. exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Prospectors, Inc.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/oil-prospectors-inc. Last Updated: August 8, 2022. Original Published Date: May 13, 2016.

.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 1, 2018 | Petroleum Companies

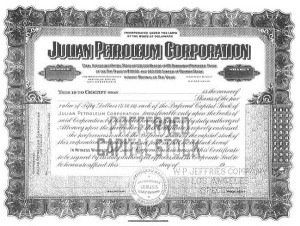

Buyers beware. While the U.S. petroleum industry has made the nation a world power with the best standard of living, there have been those who have taken advantage of “oil fever” among investors since the first commercial well in 1859. C.C. Julian and his Julian Petroleum Corporation was one. (more…)

Buyers beware. While the U.S. petroleum industry has made the nation a world power with the best standard of living, there have been those who have taken advantage of “oil fever” among investors since the first commercial well in 1859. C.C. Julian and his Julian Petroleum Corporation was one. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jun 15, 2015 | Petroleum Companies

Chances are people seeking financial information here at Old Oil Stocks – L will not find lost riches – see Not a Millionaire from Old Oil Stock. The American Oil & Gas Historical Society, which depends on donations, does not have resources to provide free research of corporate histories.

However, AOGHS continues to look into forum queries as part of its energy education mission. Some investigations have revealed little-known stories like Buffalo Bill’s Shoshone Oil Company; many others have found questionable dealings during booms and epidemics of “black gold” fever like Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

Visit the Stock Certificate Q & A Forum and view company updates regularly added to the A-to-Z listing at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? AOGHS will continue to look into forum queries, including these “in progress.”

La Lomita Oil Syndicate

La Lomita Oil Syndicate began drilling near Mission, Texas, in 1920. The Hildalgo County well’s progress was tracked by a number of contemporary publications, including the Oil Trade Journal and Oil Weekly. By October 2, the Oblate Fathers No. 1 well reached 2,700 feet deep.

A week later, the San Antonio Express newspaper reported the syndicate’s well had added another 45 feet, but was confronted with stuck tools, requiring “fishing” of equipment stuck downhole.

The recovery effort stalled drilling for more than a month. Nonetheless, by February 1921 the well was reported to have a “showing of gas” and La Lomita Oil Syndicate was setting the well’s cement casing. Records are scant thereafter, but the September 30, 1922, issue of The Oil Weekly reported another problem well for La Lomita Oil Syndicate.

“La Lomita oil Syndicate’s Hill 3, trying to sdtr [sidetrack] 3,185 feet.” Sidetracking often resulted from stuck tools and failed fishing attempts. The process required plugging of the lower well-bore and drilling around the obstruction. The drill pipe allowed some flexibility for deviation from the vertical in an effort to save the well. Whether or not La Lomita oil Syndicate was successful in this effort remains mysterious, because the company disappears from records soon thereafter.

Lewiston-Clarkston Oil & Gas Company

Lewiston-Clarkston Oil and Gas Company was one of many companies that searched for oil unsuccessfully in the state of Washington. Lewiston, Idaho, is on the east side of the Snake River; Clarkston is across the river in Washington.

It was not until 1957 that Washington’s first and only commercial producer was discovered, The Sunshine Mining Company’s Medina No. 1, was coimpleted at 223 barrels of oil a day near Ocean City. It produced 12,500 barrels before being shut down in 1961.Lewiston-Clarkston Oil & Gas drilled two consecutive dry holes in Asotin County, Washington, near Swallow Rock and then appears to have run out of money. The wells (Section 5, Township 10 North, Range 46 East) reached depths of only 800 feet and 1,600 feet, according to driller’s logs.

Washington’s commissioner of public lands reported in 2010 about 600 wells had been drilled in the state, “but large-scale commercial production has never occurred. The most recent production, which was from the Ocean City Gas and Oil Field west of Hoquiam, ceased in 1962, and no oil or gas have been produced since that time.” Read about other historic wildcat wells in First Oil Discoveries.

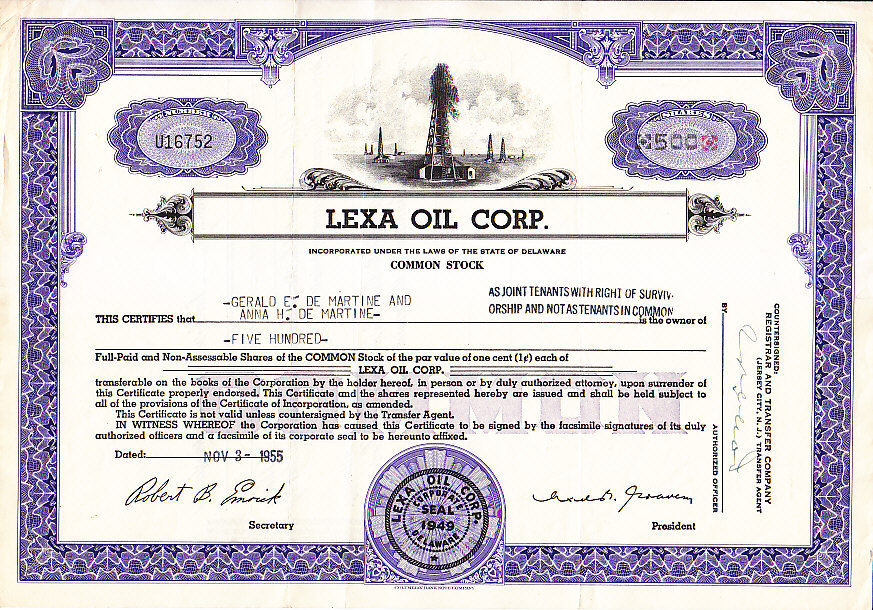

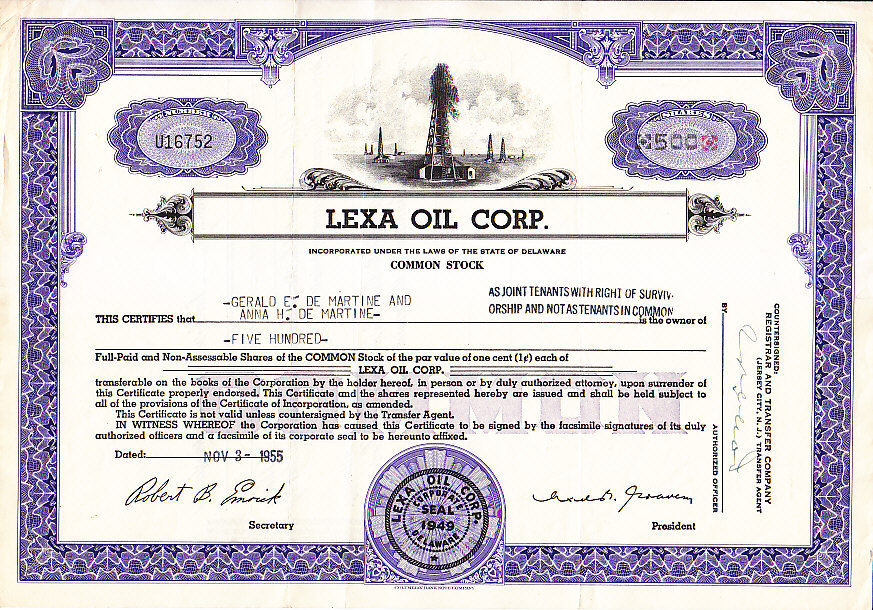

Lexa Oil Company

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included:

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included:

• The company had a well producing 250 barrels of oil a day;

• revenue from stock sales would be used for working capital;

• shares were being offered at a lower price than on the open market;

• Lexa Oil would be listed on a stock exchange;

• the investment was certain to produce high profits.

One offender received five years suspended and years’ probation. The other got two years probation. A total of 27,300 obsolete and valueless shares of Lexa Oil were destroyed by the Depository Trust Company in 2011.

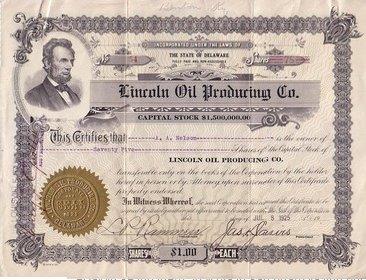

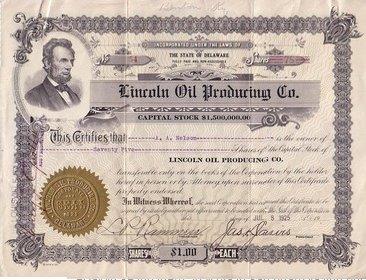

Lincoln Oil Producing Company

Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.

Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.

By 1919, dissatisfied minority shareholders brought successful suit against the “corporation and those in control of it” to cancel more than 680,000 shares of stock “for fraud.”

By 1921 – after extensive litigation – Lincoln Oil Producing Company was in receivership. The company attempted to recover in court and brought suit in 1925 but did not succeed despite multiple appeals. In 1929, a court ruling noted, “of those primarily liable, if liability existed, some were dead, some were gone from Kentucky, and some insolvent.”

Liquid Gold Oil Company

The Texas Railroad Commission may have information about Houston-based Liquid Gold Oil Company circa 1920. The commission has microfilm records that reach that booming era of Texas oil drilling. There have been other like-named companies that left behind better records (e.g., Montana Liquid Gold Oil Company incorporated in 1930 and drilled at least one well in Toole County). Another “liquid gold” corporation was active in the 1970s, but was bankrupt by 1982.

Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum Company

Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum Company in 1920 declared its stock would pay a 100 percent dividend. For $1 a share, the company’s stock could be purchased by mailing in a coupon with payment. To see this advertisement, do an internet search with quotes for “Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum” and your search should bring you to the December 3, 1920, issue of the Mexia (Texas) Weekly Herald. The enthusiastic Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum advertisement is typical of the times.

Like many under-capitalized and speculative ventures, Louisiana Consolidated Petroleum exaggerated its financial potential. Extravagant and unsubstantiated stock promotions were as common as patent medicine advertisements. “Blue Sky” laws requiring more accurate disclosures later became part of the investment landscape. State laws targeted those “engaging in any practice or transaction or course of business relating to the purchase, exchange, investment advice, or sale of securities or commodities which is fraudulent, or in violation of law, or would operate as a fraud on the purchaser.”

Love Petroleum Company

Love Petroleum Company was founded by James Wesley Love and registered in Mississippi on July 1, 1930. It drilled successful oil and natural gas wells along with dry holes. Love, who died in 1957, was noted for developing Louisiana’s Tullos-Urania oilfield.

The Mississippi Oil and Gas Board maintains records that can be seen online. By the 1990s Love Petroleum had been acquired by Southwest Royalties Inc. and had exited Mississippi to conduct business out of Midland, Texas. Southwest Royalties was acquired by Clayton Williams Energy Inc.

Loy Oil Company

Loy Oil Company was formed by the former mayor of Chanute, Kansas, and long-time independent drilling contractor Henry Wilbert “Bert” Loy in 1935, when he was 64 years old. Loy had helped pioneer the petroleum business in eastern Kansas after moving to Chanute in 1903 from Aurora, Missouri.

Loy drilled successful wells as early as 1909; these can be located in the Kansas Geological Survey oil and gas well database. The records do not indicate that Loy Oil Company survived; Henry Wilbert Loy died in 1953 at 81. The Chanute Historical Society maintains a website and contact information which may further assist in research. Learn Kansas oil history in Kansas Oil Boom.

Lucky Long Oil Company

The Lucky Long Oil Company organized on January 4, 1918, with capitalization of $50,000 divided into five million shares of stock at one cent par value.

Promoters received 1,250,000 shares with the balance held in the treasury while stock sales commissions of 25 percent were paid mostly to the company’s officers. As reported in Denver’s June 1918 Municipal Facts publication, Lucky Long Oil was specifically named in a “blue sky” investigation whose objective was to “Warn Investors Against Fake Stocks.”

The investigation revealed Lucky Long Oil had lured potential investors with spurious “guaranteed 24 percent dividends per year” and sold stock before acquiring any leases. Lucky Long Oil was assessed to have “not even a long chance speculative value” and blasted for using “clearly untruthful and misleading” advertising. President A.J. Long absconded to Wyoming and Lucky Long Oil Company disappeared.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2020 Bruce A. Wells.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 24, 2013 | Petroleum Companies

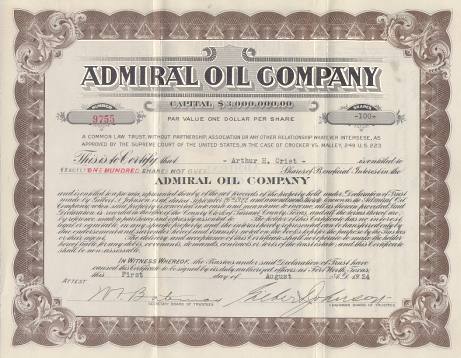

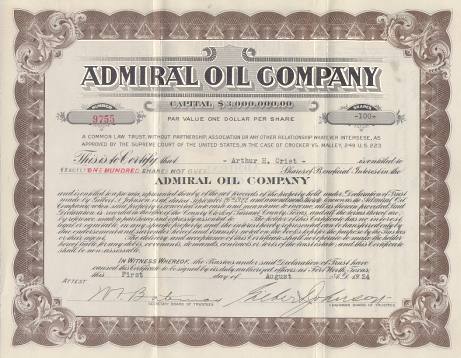

The man behind Admiral Oil Company ended up on an island – a federal penitentiary in Puget Sound, Washington.

The man behind Admiral Oil Company ended up on an island – a federal penitentiary in Puget Sound, Washington.

Admiral Oil was one of many sham companies created by Gilbert S. Johnson, who was indicted October 5, 1922, in Los Angeles.

A grand jury determined that Johnson “did devise and intend to devise, a certain scheme and artifice to defraud and to obtain money and property, by means of false and fraudulent pretenses, representations and promises.” (more…)

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included:

A fraudulent telephone campaign selling Lexa Oil Company stock resulted in two convictions. The pitchmen’s prevarications included: Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value.

Kentuckians J.C. McCombs and H.A. Moore incorporated McCombs Oil Company in Delaware on September 7, 1917. It was soon renamed McCombs Producing & Refining Company and then Lincoln Oil Producing Company. Capitalization was five million shares at $1 par value. The man behind Admiral Oil Company ended up on an island – a federal penitentiary in Puget Sound, Washington.

The man behind Admiral Oil Company ended up on an island – a federal penitentiary in Puget Sound, Washington.