First Gas Pump and Service Station

Modern gasoline pumps began in the 1880s with a device for dispensing kerosene at an Indiana grocery store.

Presaging the first gas pump, S.F. (Sylvanus Freelove) Bowser sold his newly invented kerosene pump to the owner of a grocery store in Fort Wayne, Indiana, on September 5, 1885. Less than two decades later, the first purposely built drive-in gasoline service station opened in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Bowser designed a simple device for reliably measuring and dispensing kerosene — a product in high demand as lamp fuel for half a century. His invention soon evolved into the metered gasoline pump.

Gas pumps with dials were followed by calibrated glass cylinders. Meter pumps using a small glass dome with a turbine inside replaced the measuring cylinder as pumps continued to evolve. Illustration courtesy Popular Science, September 1955.

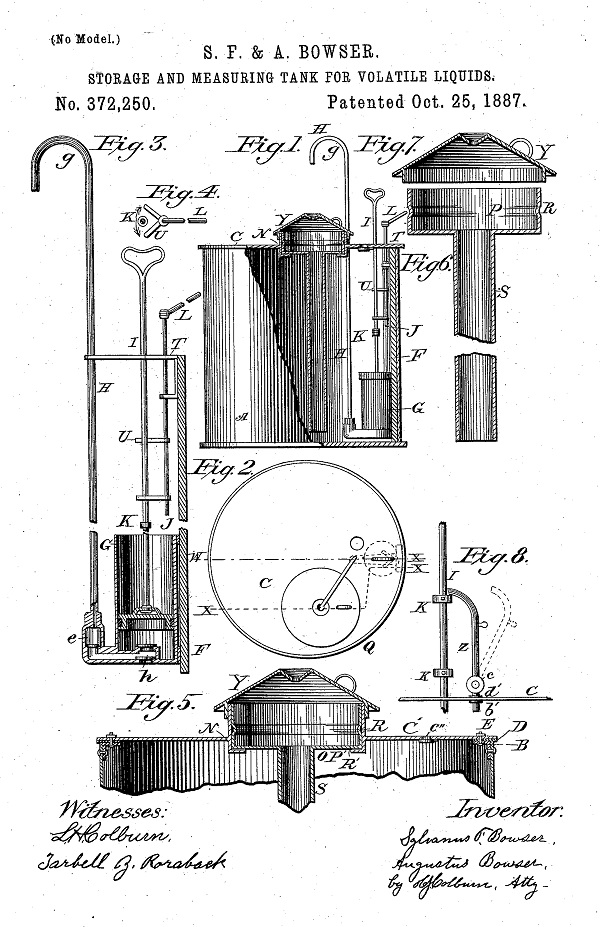

Originally designed to safely dispense kerosene as well as “burning fluid, and the light combustible products of petroleum,” early S.F. Bowser pumps had marble valves with wooden plungers and upright faucets.

With the pump’s popular success at Jake Gumper’s grocery store, Bowser formed the S.F. Bowser & Company and patented his invention in late October 1887.

Bowser’s 1887 patent was a pump for “such liquids as kerosene-oil, burning-fluid, and the light combustible products of petroleum.”

As consumer demand for kerosene (and soon, gasoline) grew, Bowser’s innovative device and those that followed faced competition from other manufacturers of self-measuring pumps. In Wayne, Indiana, the Wayne Oil Tank & Pump Company designed and built 50 of a new model in 1892, the company’s first year of business (learn more in Wayne’s Self-Measuring Pump).

S.F. Bowser’s “Self-Measuring Gasoline Storage Pumps” became known as “filling stations.” A clamshell lid closed for security when unattended.

Despite the competition, in the early 1900s – as the automobile’s popularity grew – Bowser’s company became hugely successful. His grocery store pump consisted of a square metal tank with a wooden cabinet equipped with a suction pump operated by hand-stroked lever action.

Beginning in 1905, Bowser added a hose attachment for dispensing gasoline directly into the automobile fuel tank. The S. F. Bowser “Self-Measuring Gasoline Storage Pump” became known to motorists as a “filling station” as more design innovations followed.

A 1922 Bowser advertisement illustrating the size of S.F. Bowser’s Fort Wayne, Indiana, manufacturing facility and six-floor headquarters similar to early Chicago skyscrapers.

S.F. Bowser died on October 3, 1938, and the manufacturing company he founded maintained its presence on Creighton Avenue in Fort Wayne until being demolished in 2012.

“In Fort Wayne today, the only reminder of Bowser’s legacy is a street named in his honor,” reported Indiana landmarks in 2017, adding, “In parts of Europe and Australia, however, people still refer to a gasoline pump generically as a ‘bowser.'”

The popular Bowser Model 102 Chief Sentry with its “clamshell” cover offered security when the pump was left unattended (see the 1920 Diamond Filling Station in Washington, D.C.).

Manufactured in 1911, an S.F. Bowser Model 102 “Chief Sentry” pumped gas on North Capitol Street in Washington D.C., in 1920. The Penn Oil Company’s pump’s topmost globe, today prized by collectors, survived only as a bulb. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

With the addition of competing businesses such as Wayne Pump Company and Tokheim Oil Tank & Pump Company, the city of Fort Wayne, Indiana, became the gas-pump manufacturing capital of the world.

Some enterprising manufacturing companies even came up with coin-operated gas pumps.

Penn Oil Company filling stations were the exclusive American distributor of Lightning Motor Fuel, a British product made up of “50 percent gasoline and 50 percent of chemicals, the nature of which is secret.” The secret ingredient was likely alcohol. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

First Drive-In Service Station

Although Standard Oil will claim a Seattle, Washington, station of 1907, and others argue about one in St. Louis two years earlier, most agree that when “Good Gulf Gasoline” went on sale, Gulf Refining Company opened America’s first true drive-in service station.

Gulf Refining Company had been established in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1901 by Andrew Mellon and other investors as an expansion of the J. W. Guffey Petroleum Company formed earlier the same year to exploit the Spindletop oilfield discovery in Texas. The company’s motoring milestone took place at the corner of Baum Boulevard and St. Clair Street in downtown Pittsburgh on December 1, 1913.

Unlike earlier simple curbside gasoline filling stations, an architect purposefully designed the pagoda-style brick facility that offered free air, water, crankcase service, and tire and tube installation.

Gulf Refining Company’s decision in 1913 to open the first service station (above) along Baum Boulevard in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was no accident. The roadway had become known as “automobile row'” because of its high number of dealerships. Photo courtesy Gulf Oil Historical Society.

“This distinction has been claimed for other stations in Los Angeles, Dallas, St. Louis and elsewhere,” noted a Gulf corporate historian. “The evidence indicates that these were simply sidewalk pumps and that the honor of the first drive-in is that of Gulf and Pittsburgh.”

The Gulf station included a manager and four attendants standing by. The original service station’s brightly lighted marquee provided shelter from bad weather for motorists. A photo of the station, designed by architect J.H. Giesey, may or may not have been taken on opening day, according to the Gulf Oil Historical Society.

“At this site in Dec. 1913, Gulf Refining Co. opened the first drive-in facility designed and built to provide gasoline, oils, and lubricants to the motoring public,” noted a Pennsylvania historical marker dedicated on July 11, 2000.

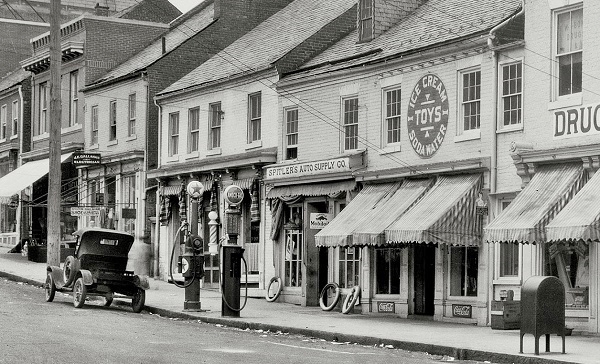

Spitlers Auto Supply Company, 205 Commerce Street, Fredericksburg, Virginia, closed in 1931. It was an example of curbside pumps used before Gulf Refining Company established covered, drive-through stations.

The drive-in station sold 30 gallons of gasoline at 27 cents per gallon on its first day, according to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

“Prior to the construction of the first Gulf station in Pittsburgh and the countless filling stations that followed throughout the United States, automobile drivers pulled into almost any old general or hardware store, or even blacksmith shops in order to fill up their tanks,” the historical commission noted at ExplorePAhistory.com.

The decision to open the first station along Baum Boulevard in Pittsburgh was no accident. When the station was opened, Baum Boulevard had become known as “automobile row” because of the high number of dealerships that were located along the thoroughfare.

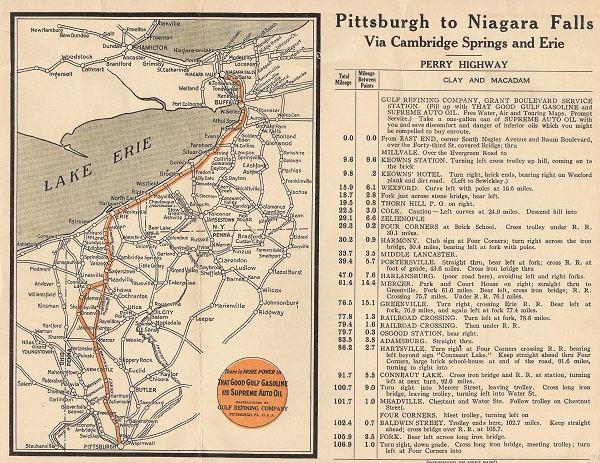

Until about 1925, Gulf Refining Company was the only oil company to issue maps. Gulf was formed in 1901 by members of the Mellon family of Pittsburgh. Map image courtesy Harold Cramer.

“Gulf executives must have figured that there was no better way to get the public hooked on using filling stations than if they could pull right in and gas up their new car after having just driven it off the lot,” noted a commission historian.

In addition to gas, the Gulf station also offered free air and water — and sold the first commercial road maps in the United States. “The first generally distributed oil company road maps are usually credited to Gulf,” said Harold Cramer in his “Early Gulf Road Maps of Pennsylvania.”

This 1916 Bowser gasoline pump operated by a hand crank and “clock face” dial. Photo from the Smithsonian Collection.

“The early years of oil company maps, circa 1915 to 1925, are dominated by Gulf as few other oil companies issued maps, and until about 1925 Gulf was the only oil company to issue maps annually,” Cramer explained. That would change.

Founded in 1996, the Road Map Collectors Association (RMCA) preserves the history of road maps to educate the public about America’s automobile age, also documented and exhibited by the Smithsonian Institution (see America on the Move).

While the Gulf station in Pittsburgh could be considered the first “modern” service station, kerosene and gasoline “filling stations” helped pave the way.

Memorabilia once exhibited at the Northwoods Petroleum Museum outside Three Lakes, Wisconsin, opened by Ed Jacobsen in 2006 and closed in 2024.

“At the turn of the century, gasoline was sold in open containers at pharmacies, blacksmith shops, hardware stores and other retailers looking to make a few extra dollars of profit,” noted Kurt Ernst in a 2013 article.

“In 1905, a Shell subsidiary opened a filling station in St. Louis, Missouri, but it required attendants to fill a five gallon can behind the store, then haul this to the customer’s vehicle for dispensing…A similar filling station was constructed by Socal gasoline in Seattle, Washington, opening in 1907,” Ernst explained in his article “The Modern Gas Station celebrates its 100th Birthday.”

One-hundred years after the Gulf Refining Company station opened, America’s 152,995 operating gas stations included 123,289 convenience stores, according to Ernst. On average, each location sold about 4,000 gallons of fuel per day, “quite a jump from the 30 gallons sold at the Gulf station in Pittsburgh on December 1, 1913.”

Photographs of early service stations remain an important part of preserving U.S. transportation history (also true for architecture, pump technologies, advertising methods, and more). The American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s Dome Gas Station at Takoma Park offers insights revealed in just one 1921 black-and-white photograph of a station in a Washington, D.C., suburb.

The Library of Congress maintains a large collection of service station images, as do other libraries and organizations listed with it in AOGHS photo resources.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Pump and Circumstance: Glory Days of the Gas Station (1993); Fill’er Up!: The Great American Gas Station

(2013); The American Highway: The History and Culture of Roads in the United States

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “First Gas Pump and Service Station.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/first-gas-pump-and-service-stations. Last Updated: December 1, 2025. Original Published Date: March 14, 2013.