by Bruce Wells | Feb 23, 2026 | This Week in Petroleum History

February 23, 1906 – Flaming Kansas Gas Well makes Headlines –

A small town in southeastern Kansas found itself making headlines when a natural gas well erupted into flames after a lightning strike. The 150-foot burning tower could be seen at night for 35 miles. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 22, 2026 | Petroleum Technology

Inventing technologies for protecting oil and natural gas wells and the environment.

Erle P. Halliburton in March 1921 received a U.S. patent for his improved method for cementing oil wells, helping to bring greater production and environmental safety to America’s burgeoning oilfields.

When Halliburton patented his “Method and Means for Cementing Oil Wells,” the 29-year-old inventor changed how oil and natural gas wells were completed. His contribution to oilfield production technology was just beginning. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 21, 2026 | Petroleum History Almanac

Famed lawman and wife gambled on Kern County oil leases.

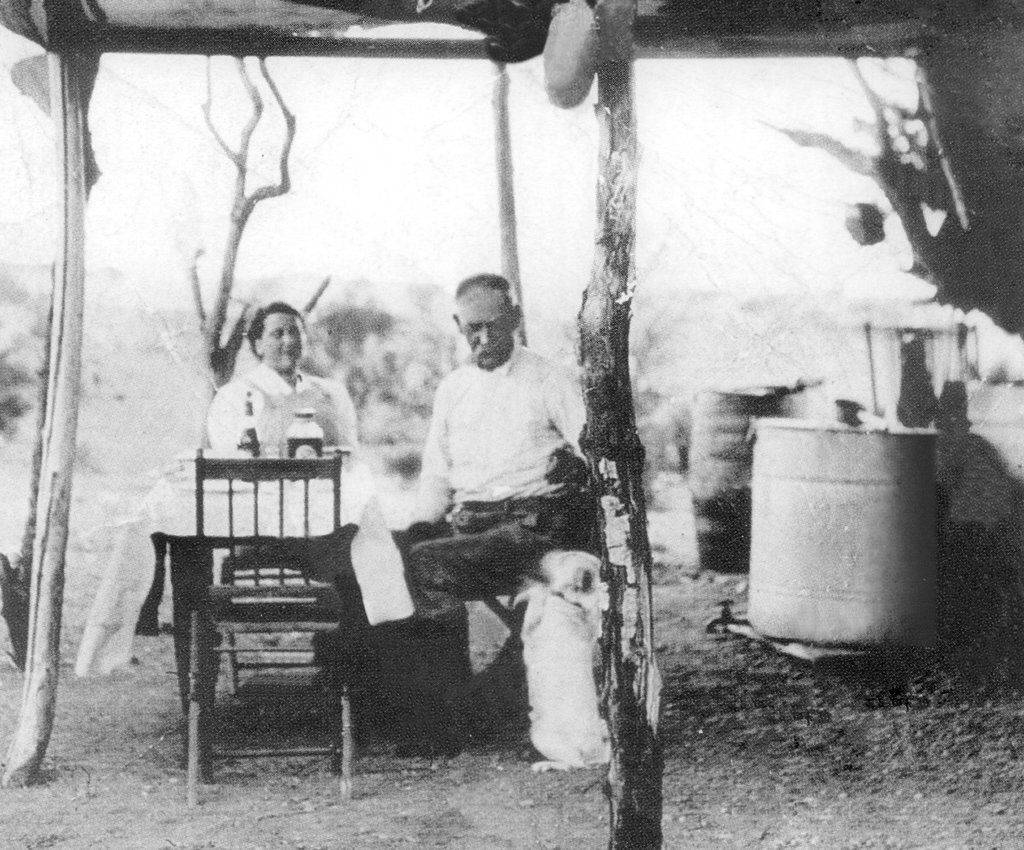

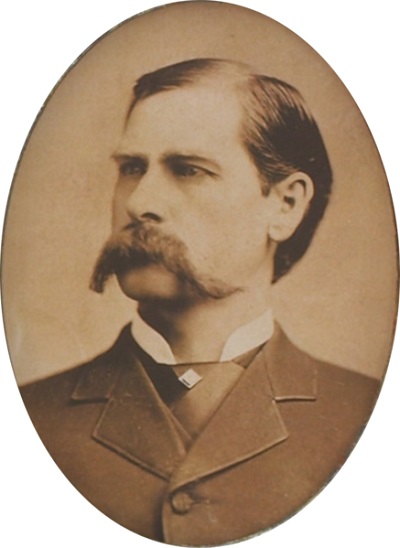

Old West lawman and gambler Wyatt Earp and his wife Josie in 1920 bet oil could be found on a barren piece of California scrub land. A century later, his Kern County lease still paid royalties.

Ushered into modest retirement by notoriety, Mr. and Mrs. Wyatt Earp were known — if not successful — entrepreneurs with abundant experience running saloons, gambling houses, bordellos (Wichita, Kansas, 1874), real estate, and finally western mining ventures.

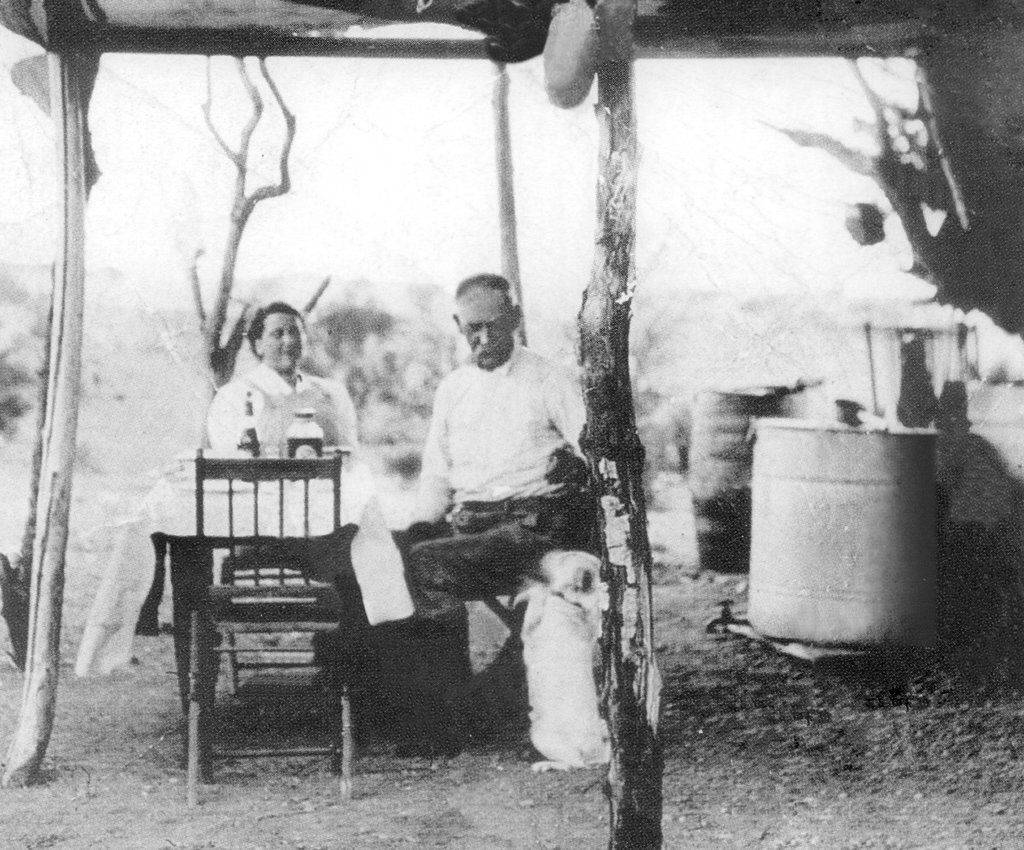

Circa 1906 photo of Wyatt Earp and wife Josie at their mining camp with dog “Earpie.”

Quietly retired in California, the couple alternately lived in suburban Los Angeles or tended to gold and copper mining holdings at their “Happy Days” camp in the Whipple Mountains near Vidal. Josephine “Josie” Marcus Earp had been by Wyatt’s side since his famous 1881 O.K. Corral gunfight in Tombstone, Arizona.

Also in California, Josie’s younger sister, Henrietta Marcus, had married into wealth and thrived in Oakland society while Josie and Wyatt roamed the West. “Hattie” Lehnhardt had the genteel life sister Josie always wanted but never had. When Hattie’s husband Emil died by suicide in 1912, the widow inherited a $225,000 estate.

Money had always been an issue between the Earps, according to John Gilchriese, amateur historian and longtime collector of Earp memorabilia.

Josie liked to remind Wyatt he had once employed a struggling gold miner — Edward Doheny — as a faro lookout (armed bouncer) in a Tombstone saloon. Doheny later drilled for oil and discovered the giant Los Angeles oilfield in the early 1880s.

The Los Angeles field launched Southern California’s petroleum industry, creating many unlikely oil millionaires — including local piano teacher Emma Summers, whose astute business sense earned her the title “Oil Queen of California.”

In addition to oilman Doheny, Earp socialized with prominent Californians like George Randolph Hearst (father of San Francisco Examiner publisher William), whom he knew from mining days in Tombstone. But the former lawman’s ride into the California oil patch began in 1920 when he gambled on an abandoned placer claim.

Kern County Lease

In 1901, a petroleum exploration venture had drilled a wildcat well about five miles north of Bakersfield in Kern County. The attempt generated brief excitement, but nothing ultimately came of it. When Shasta Oil Company drilled into bankruptcy after three dry holes, the land returned to its former reputation — worthless except for sheep grazing.

Earp decided to bet on black gold where Shasta Oil had failed. But first, California required that he post a “Notice of Intent to File Prospectors Permit.” He sent his wife to make the application. But on her way to pay the fees with paperwork in hand, Josie was diverted by gaming tables. She lost all the money, infuriating Wyatt and delaying his oil exploration venture.

Earp later secured the Kern County lease claim he sought, mostly with money from his sister-in-law, Hattie Lehnhardt,

Wyatt Earp purchased a mineral lease in Kern County, PLSS (Public Land Survey System) Section 14, Township 28 South, Range 27 East.

The San Francisco Examiner declared, “Old Property Believed Worthless for Years West of Kern Field Relocated by Old-Timers.” The newspaper — describing Earp as the “pioneer mining man of Tombstone” — reported that the old Shasta Oil Company parcel had been newly assessed.

“Indications are that a great lake of oil lies beneath the surface in this territory,” the article proclaimed. “Should this prove to be the case, the locators of the old Shasta property have stumbled onto some very valuable holdings.”

Meanwhile, competition among big players like Standard Oil of California and Getty Oil energized the California petroleum market. By July 1924, Getty Oil had won the competition and began to drill on the Earp lease.

On February 25, 1926, a well on the lease was completed with production of 150 barrels of oil a day. During 1926, nine of the wells produced a total of almost 153,000 barrels of oil. “Getty has been getting some nice production in the Kern River field ever since operations were started,” reported the Los Angeles Times.

Rarely exceeding 300 barrels of oil a day, the Getty wells were not as large as other recent California discoveries (see Signal Hill Oil Boom), but they produced oil from less than 2,000 feet deep, keeping production costs low. Royalty checks would begin arriving in the mail.

With the Oil and Gas Journal reporting “Kern River Front” oil selling for 75 cents per barrel, the Earps received $3,174 from 12 active wells producing 282,116 barrels of oil from February 1927 to January 1928, according to the 2019 book A Wyatt Earp Anthology: Long May His Story Be Told.

At age 78, Wyatt Earp’s oil gamble finally paid off — but there was a catch.

No Royalty Riches

Because of her gambling, Josie Earp had become so notoriously incapable of managing money that Earp gave control of the lease to her younger sister, Hattie Lehnhardt. At the same time, he directed that his wife “receive at all times a reasonable portion of any and all benefits, rights and interests.”

From February 1928 to January 1929, production from the dozen Earp wells declined to 91,770 barrels, “grossing $68,827 with Josie’s royalties amounting to a mere $1,032,” noted the anthology’s editors.

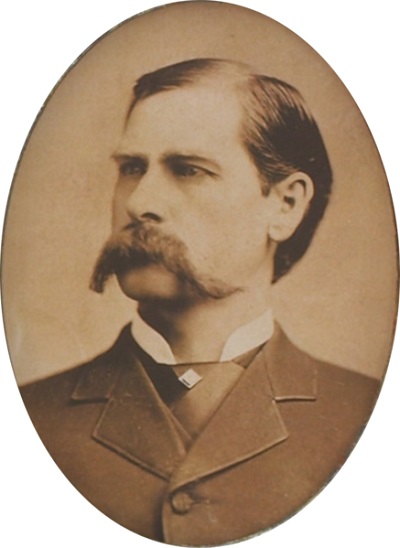

Circa 1887 portrait of Wyatt Earp at about 39 years old.

With that, Earp’s venture in the Kern County petroleum business became a footnote to his legend, already well into the making. By the time of his death on January 13, 1929, his gamble on oil, still known as the Lehnhardt Lease, had paid Josie a total of almost $6,000.

The disappointing results would prompt Josie to write, “I was in hopes they would bring in a two or three hundred barrel well. But I must be satisfied as it could have been a duster, too.”

When benefactor Hattie Lehnhardt died in 1936, her children (and some litigation) put an end to the 20 percent of the 7.5 percent of the Getty Oil royalties formerly paid to their widowed aunt Josephine. Eight years later, when Josephine died, she left a total estate of $175, including a $50 radio and a $25 trunk.

The Lehnhardt lease in Kern County would remain active. From January 2018 to December 2022, improved secondary recovery in the Lehnhardt oil properties of the California Resources Production Corporation produced 440,560 barrels of oil, according to records at ShaleXP.

Kern County Museums

Beginning in 1941, the Kern County Museum in Bakersfield has educated visitors with petroleum exhibits on a 16-acre site just north of downtown. The museum offers “Black Gold: The Oil Experience,” a permanent $4 million science, technology, and history exhibition.

The museum also preserves a large collection of historic photographs.

A roughneck monument with a 30-foot-tall derrick was dedicated in Taft, California, in 2010. Photo courtesy West Kern Oil Museum.

In Taft, the West Kern Oil Museum also has images from the 1920s showing more than 7,000 wooden derricks covering 21 miles in southwestern Kern County, according to Executive Director Arianna Mace.

Run almost entirely by volunteers — and celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2023 — the oil museum collects, preserves, and exhibits equipment telling the story of the Midway-Sunset field, which, by 1915, produced half of the oil in California. The state led the nation in oil production at the time.

Since 1946, Taft residents have annually celebrated “Oildorado.” The community in 2010 dedicated a 30-foot Oil Worker Monument with a derrick and bronze sculptures of Kern County petroleum pioneers.

Both Kern County museums played credited roles in the 2008 Academy Award-winning movie “There Will Be Blood.” Production staff visited each museum while researching realistic California wooden derricks and oil production machinery. During a visit to the West Kern Oil Museum, the film’s production designer purchased copies of authentic 1914 cable-tool derrick blueprints.

______________________

Recommended Reading: A Wyatt Earp Anthology: Long May His Story Be Told (2019); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry  (2016); Early California Oil: A Photographic History, 1865-1940

(2016); Early California Oil: A Photographic History, 1865-1940 (1985); Pico Canyon Chronicles: The Story of California’s Pioneer Oil Field

(1985); Pico Canyon Chronicles: The Story of California’s Pioneer Oil Field (1985); Black Gold, the Artwork of JoAnn Cowans

(1985); Black Gold, the Artwork of JoAnn Cowans (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support AOGHS to help maintain this energy education website, a monthly email newsletter, This Week in Oil and Gas History News, and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Wyatt Earp’s California Oil Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/wyatt-earps-california-oil-wells. Last Updated: February 19, 2026. Original Published Date: October 30, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 20, 2026 | Petroleum Companies

Like his friend “Buffalo Bill,” Oklahoma showman Maj. Gordon W. “Pawnee Bill” Lillie caught oil fever.

With America joining “the war to end all wars” in Europe and oil demand rising, a popular Oklahoma showman launched his own petroleum exploration and refining company.

Although not as well known as his friend Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody of Wyoming, Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie was “a showman, a teacher, and friend of the Indian,” according to his biographer.

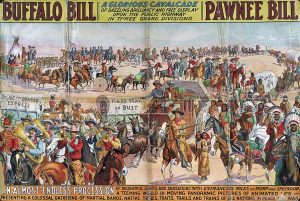

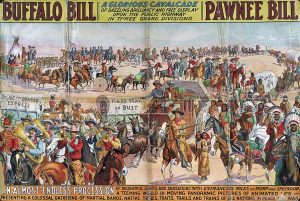

Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie combined their shows from 1908 to 1913 as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East.”

Maj. Lillie was admired for being a “colonizer in Oklahoma and builder of his state,” noted Stillwater journalist Glenn Shirley in his 1958 book Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie.

The two entertainers joined their shows in 1908 to form “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East,” promoted as “a glorious cavalcade of dazzling brilliancy,” noted Shirley, adding that the combined shows offered “an almost endless procession of delightful sight and sensations.”

But times were changing as public taste turned to a new form of entertainment, motion picture shows. By 1913, the two showmen’s partnership was over, and their western cavalcade was foreclosed. Lillie turned to other ventures — real estate, banking, ranching, and like his former partner, the petroleum industry (see Buffalo Bill Shoshone Oil Company).

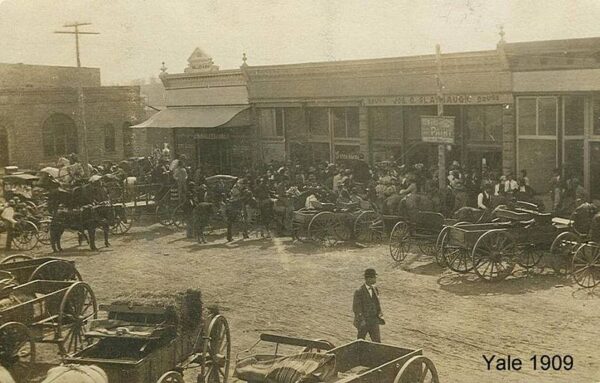

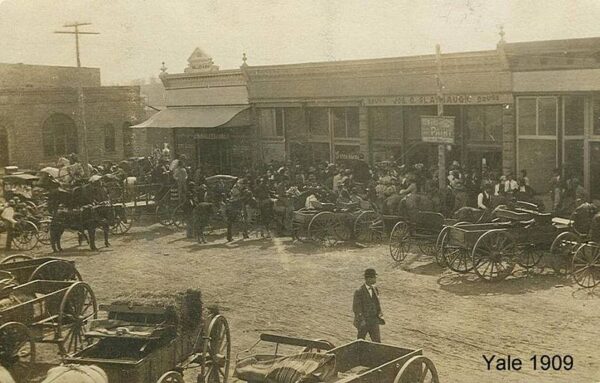

Oklahoma oilfield discoveries near Yale (population of only 685 in 1913) had created a drilling boom that made it home to 20 oil companies and 14 refineries. In 1916, Petrol Refining Company added a 1,000-barrel-a-day-capacity plant in Yale, about 25 miles south of Lillie’s ranch.

The trade magazine Petroleum Age, which had covered the 1917 “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery in Texas, reported that for Pawnee Bill, “the lure of the oil game was too strong to overcome.”

Obsolete financial stock certificates with interesting histories, like Pawnee Bill Oil Company are valued by collectors.

The Oklahoma showman founded the Pawnee Bill Oil Company on February 25, 1918, and bought Petrol Refining’s new “skimming” refinery in March.

An early type of refining, skimming (or topping) removed light oils, gasoline, and kerosene and left a residual oil that could also be sold as a basic fuel. To meet the growing demand for kerosene lamp fuel, early refineries built west of the Mississippi River often used the inefficient but simple process.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie (1860-1942).

Lillie’s company became known as Pawnee Bill Oil & Refining and contracted with the Twin State Oil Company for oil from nearby leases in Payne County.

Under headlines like “Pawnee Bill In Oil” and “Hero of Frontier Days Tries the Biggest Game in All the World,” the Petroleum Age proclaimed:

“Pawnee Bill, sole survivor of that heroic band of men who spread the romance of the frontier days over the world…who used to scout on the ragged edge of semi-savage civilization, is doing his bit to supply Uncle Sam and his allies with the stuff that enables armies to save civilization.”

Post-War Refinery Bust

By July 30, 1919, Pawnee Bill Oil (and Refining) Company had leased 25 railroad tank cars, each with a capacity of about 8,300 gallons. But the end of “the war to end all wars” drastically reduced demand for oil and refined petroleum products. Just two years later, Oklahoma refineries were operating at about 50 percent capacity, with 39 plants shut down.

Although Lillie’s refinery was among those closed, he did not give up. In February 1921, he incorporated the Buffalo Refining Company and took over the Yale refinery’s operations. He was president and treasurer of the new company. But by June 1922, the Yale refinery was making daily runs of 700 barrels of oil, about half its skimming capacity.

The Pawnee Bill Oil Company held its annual stockholders meetings in Yale, Oklahoma, an oil boom town about 20 miles from Pawnee Bill’s ranch.

“At the annual stockholders’ meeting held at the offices of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company in Yale, Oklahoma, in April, it was voted to declare an eight percent dividend,” reported the Wichita Daily Eagle. “The officers and directors have been highly complimented for their judicious and able handling of the affairs of the company through the strenuous times the oil industry has passed through since the Armistice was signed.”

The Kansas newspaper added that although many independent refineries had been sold at receivers’ sale, “the financial condition of the Pawnee Bill company is in fine shape.”

Wild West Oil Ventures

What happened next has been hard to determine since financial records of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company are rare. A 1918 stock certificate signed by Lillie, valued by collectors one hundred years later, could be found selling online for about $2,500.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie’s friend and partner Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody also had caught oil fever, forming several Wyoming oil exploration ventures, but none of them lasted. In 1920, yet another legend of the Old West — lawman and gambler Wyatt Earp — began his a search for oil riches on a piece of California scrubland. One century later, his Kern County lease still paid royalties; learn more in Wyatt Earp’s California Oil Wells.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie (1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support AOGHS to help maintain this energy education website, a monthly email newsletter, This Week in Oil and Gas History News, and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Pawnee Bill Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pawnee-bill-oil-company. Last Updated: February 21, 2026. Original Published Date: February 24, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 19, 2026 | Petroleum Products

A Revolutionary DuPont lab product first used commercially in 1938 for toothbrush bristles.

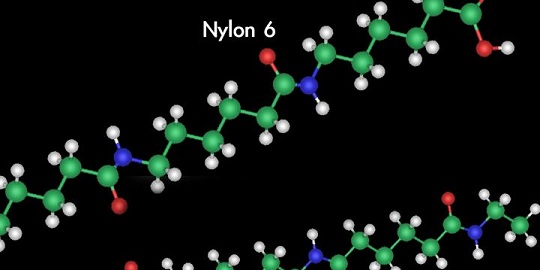

The world’s first synthetic fiber was the petroleum product “Nylon 6,” discovered in 1935 by a DuPont chemist who produced the polymer from chemicals found in oil.

DuPont Corporation foresaw the future of “strong as steel” artificial fibers. The chemical conglomerate had been founded in 1802 as a Wilmington, Delaware, manufacturer of gunpowder. The company would become a global giant after its scientists created durable and versatile products like nylon, rayon, and lucite.

“Women show off their nylon pantyhose to a newspaper photographer, circa 1942,” noted Jennifer S. Li in “The Story of Nylon – From a Depressed Scientist to Essential Swimwear.” Photo by R. Dale Rooks.

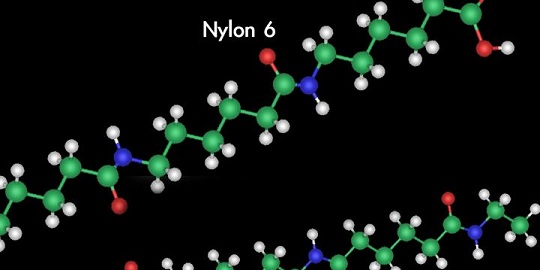

The world’s first synthetic fiber — nylon — was discovered on February 28, 1935, by a former Harvard professor working at a DuPont research laboratory. Called Nylon 6 by scientists, the revolutionary carbon-based product came from chemicals found in petroleum.

Chemists named the fiber Nylon 6 because chains of adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contained six carbon atoms per molecule.

Professor Wallace Carothers had experimented with artificial materials for more than six years. He previously discovered neoprene rubber (commonly used in wetsuits) and made major contributions to understanding polymers — large molecules composed of long chains of repeating chemical structures.

Polymer Chains

Carothers, 32, created fibers when he combined the chemicals amine, hexamethylene diamine, and adipic acid. His experiments formed polymer chains using a process in which individual molecules joined together with water as a byproduct. But the fibers were weak.

A PBS series, A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries, in 1998 noted Carothers’ breakthrough came when he realized, “the water produced by the reaction was dropping back into the mixture and getting in the way of more polymers forming. He adjusted his equipment so that the water was distilled and removed from the system. It worked!”

DuPont named the petroleum product nylon — although chemists called it Nylon 6 because the adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contain six carbon atoms per molecule.

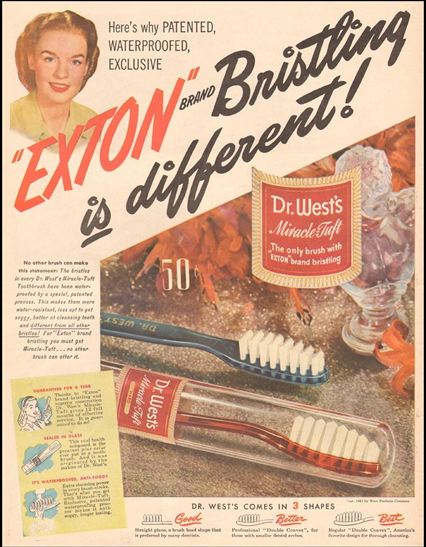

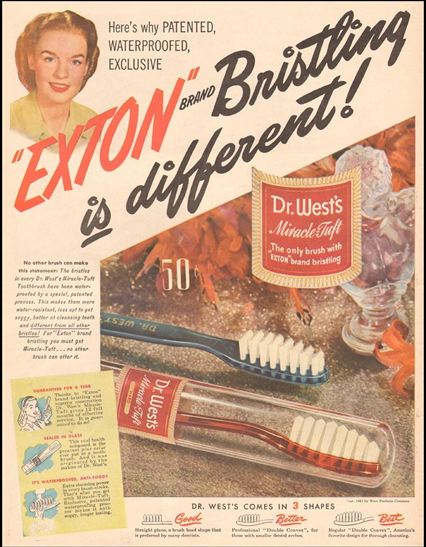

“Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” noted a 1938 magazine ad.

Each man-made molecule consists of 100 or more repeating units of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms, strung in a chain. A single filament of nylon may have a million or more molecules, each taking some of the strain when the filament is stretched.

There’s disagreement about how the product name originated at DuPont.

“As to the word ‘nylon,’ it’s actually quite arbitrary. DuPont itself has stated that originally the name was intended to be No-Run (that’s run as in the sense of the compound chain of the substance unraveling), but at the time there was no real justification for the claim, so it needed to be changed,” noted Chris Nickson in a 2017 website post, Where Does the Name Nylon Originate?

Toothbrush Bristles

The first commercial use of this revolutionary petroleum product was for toothbrushes.

On February 24, 1938, the Weco Products Company of Chicago, Illinois, began selling its new “Dr. West’s Miracle-Tuft” — the earliest toothbrush to use synthetic DuPont nylon bristles.

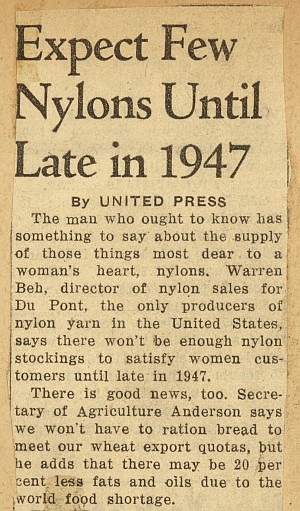

First used for toothbrush bristles, nylon women’s stockings were widely promoted by DuPont in 1948.

Americans will soon brush their teeth with nylon — instead of hog bristles, declared an article in the New York Times. “Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” explained a 1938 Weco Products advertisement in Life magazine.

“Today, Dr. West’s new Miracle-Tuft is a single exception,” the ad proclaimed. “It is made with EXTON, a unique bristle-like filament developed by the great DuPont laboratories and produced exclusively for Dr. West’s.”

Pricing its toothbrush at 50 cents, the Weco Products Company guaranteed “no bristle shedding.” Johnson & Johnson of New Brunswick, New Jersey, will introduce a competing nylon-bristle toothbrush in 1939.

Nylon Stockings

Although DuPont patented nylon in 1935, it was not officially announced to the public until October 27, 1938, in New York City.

A DuPont vice president unveiled the synthetic fiber — not to a scientific society or industry association — but to 3,000 Women’s Club members gathered at the site of the upcoming 1939 New York World’s Fair.

During WWII, nylon was used as a substitute for silk in parachutes.

“He spoke in a session entitled ‘We Enter the World of Tomorrow,’ which was keyed to the theme of the forthcoming fair, the World of Tomorrow,” explained DuPont historian David A. Hounshell in a 1988 book.

The petroleum product was an instant hit, especially as a replacement for silk in hosiery. DuPont built a full-scale nylon plant in Seaford, Delaware, and began commercial production in late 1939. The company purposefully did not register “nylon” as a trademark — choosing to allow the word to enter the American vocabulary as a synonym for “stockings.”

Women’s nylon stockings appeared for the first time at Gimbels Department Store on May 15, 1940. World War II would remove the polymer hosiery from stores since it was needed for parachutes and other vital supplies.

Nylon would become far and away the biggest money-maker in the history of DuPont. The powerful material from lab research led company executives to derive formulas for growth, according to Hounshell in The Nylon Drama.

“By putting more money into fundamental research, DuPont would discover and develop ‘new nylons,’ that is, new proprietary products sold to industrial customers and having the growth potential of nylon,” Hounshell explained in his 1988 book.

Carothers did not live to see the widespread application of his work — in consumer goods such as toothbrushes, fishing lines, luggage, and lingerie, or in special uses such as surgical thread, parachutes, or pipes — nor the powerful effect it had in launching a whole era of synthetics.

Devastated by the sudden death of his favorite sister in early 1937, Wallace Carothers committed suicide in April of that year. The DuPont Company would name its research facility after him.

The DuPont website notes that the invention of nylon changed the way people dressed worldwide and made the term ‘silk stocking’ obsolete (once an epithet directed at the wealthy elite). Nylon’s success encouraged DuPont and other companies to adopt long-term strategies for products developed from research.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History (2019); Enough for One Lifetime: Wallace Carothers, Inventor of Nylon (2005); The Nylon Drama (1988). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support AOGHS to help maintain this energy education website, a monthly email newsletter, This Week in Oil and Gas History News, and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/petroleum-product-nylon-fiber. Last Updated: February 19, 2026. Original Published Date: February 23, 2014.

View Post