by Bruce Wells | Jan 15, 2024 | This Week in Petroleum History

January 17, 1911 – Oilfield Discovery leads to North Texas Boom –

The Producers Oil Company discovered the Electra oilfield in North Texas, bringing the first commercial oil production to Wichita County. The Waggoner No. 5 well produced 50 barrels per day from a depth of 1,825 feet on land owned by local rancher William Waggoner, who had found traces of oil while drilling a water well for his cattle.

Named after rancher William Waggoner’s daughter, Electra, would become the “Pump Jack Capital of Texas.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

“At first, there weren’t any cars, and about the only thing oil was good for was to help repel chicken house mites,” noted a county historian about the discovery well, which brought more exploration. The Clayco No. 1 gusher of April 1 would send Electra’s oil fortunes further skyward, helping it become the Pump Jack Capital of Texas.

January 18, 1919 – Congregation rejects drilling in Cemetery

World War I had ended two months earlier as oil production continued to soar in North Texas. Reporting on “Roaring Ranger” oilfields, the New York Times noted that speculators had offered $1 million for rights to drill in the Merriman Baptist Church cemetery, but the congregation could not be persuaded to disturb the interred.

“Lone Star Bonanza, the Ranger Oil Boom of 1917-1923,” photograph of a North Texas church cemetery by Robert Vann.

Posted on a barbed-wire fence surrounding the graves not far from producing oil wells, a sign proclaimed, “Respect the Dead.” Today, the cemetery — and a new church — can be found three miles south of Ranger.

Learn more in Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church.

January 19, 1922 – Geological Survey predicts Oil Shortage

The U.S. Geological Survey predicted America’s oil supplies would run out in 20 years. It was not the first or last false alarm. Warnings of shortages had been made for most of the 20th century, according to geologist David Deming of the University of Oklahoma. His 1950 report, A Case History of Oil-Shortage Scares, documented six claims prior to 1950 alone.

Among the end of oil supplies predictions named in the report: The Model T Scare of 1916; the Gasless Sunday Scare of 1918; the John Bull (United Kingdom) Scare of 1920-1923; the Ickes (Interior Secretary Harold Ickes) Petroleum Reserves Scare of 1943-1944; and the Cold War Scare of 1946-1948.

Predictions of U.S. oil shortages began as early as 1879, when the Pennsylvania state geologist said remaining oil supplies would keep kerosene lamps burning for only four more years.

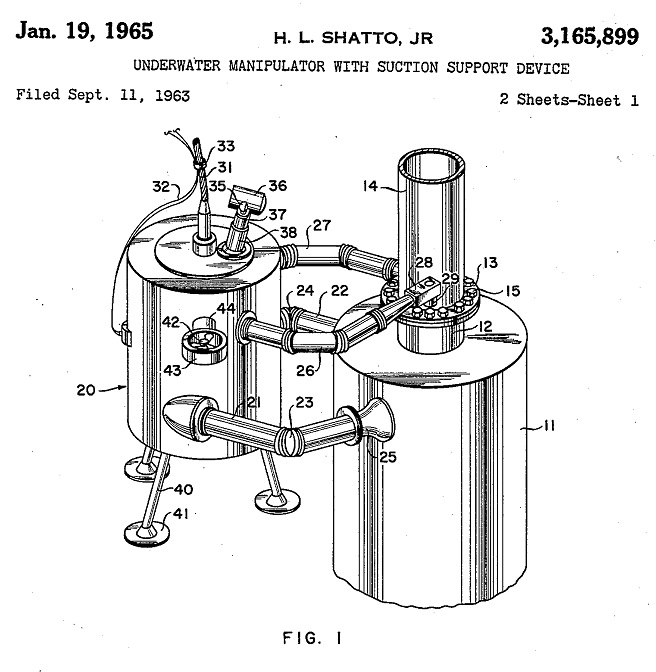

January 19, 1965 – “Underwater Manipulator” patented

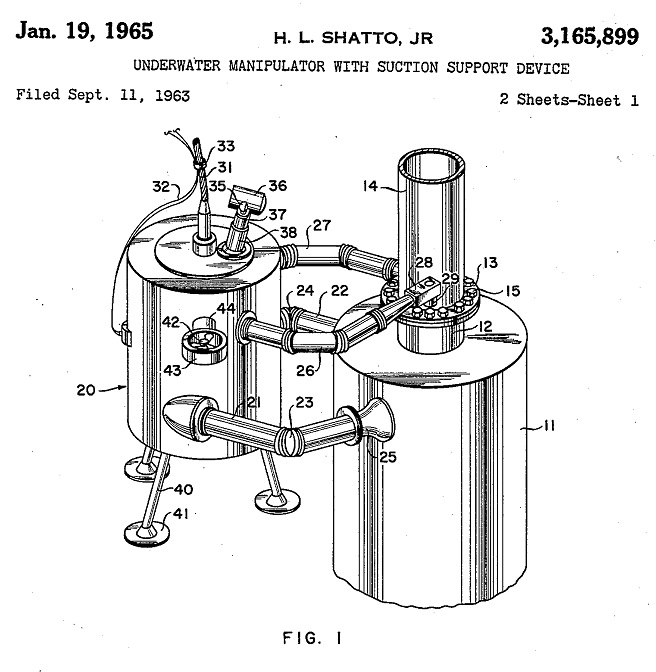

Howard Shatto Jr. received a 1965 U.S. patent for his “underwater manipulator with suction support device.” His concept led to the modern remotely operated vehicle (ROV) now used most widely by the offshore petroleum industry. Shatto helped make Shell Oil Company an early leader in offshore oilfield technologies.

Howard Shatto Jr. would become “a world-respected innovator in the areas of dynamic positioning and remotely operated vehicles.”

Underwater robot technology can trace its roots to the late 1950s, when Hughes Aircraft developed a Manipulator Operated Robot — MOBOT — for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Beginning in 1960, Shell Oil began transforming the landlocked MOBOT into a marine robot, “basically a swimming socket wrench,” noted one engineer.

In his 1965 patent — one of many he received — Shatto explained how his robot could install production equipment at greater depths than divers could safely work. The ROV inventor also would become known as the offshore industry’s father of dynamic positioning.

Learn more in ROV – Swimming Socket Wrench.

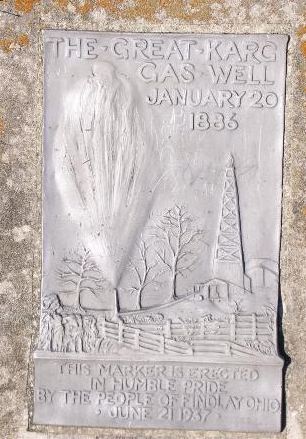

January 20, 1886 – Great Karg Well erupts Natural Gas in Ohio

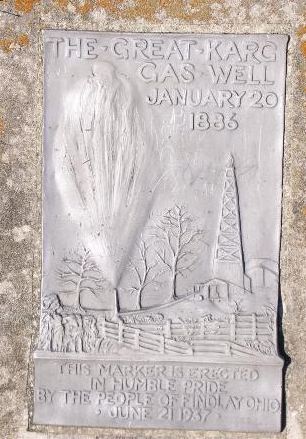

The spectacular natural gas well – the “Great Karg Well” of Findlay, Ohio — erupted with an initial flow of 12 million cubic feet a day. The well’s gas pressure could not be controlled by technology of the day, and it ignited into a towering flame that burned for four months — becoming a popular Ohio tourist attraction. Eight years earlier, another natural gas well in Pennsylvania had made similar headlines (see Natural Gas is King in Pittsburgh).

A plaque dedicated in 1937 in Findlay, Ohio, commemorated the state’s giant natural gas discovery of 1886.

Although Ohio’s first natural gas well was drilled in Findlay in 1884 by Findlay Natural Gas Company, the Karg well launched the state’s first major gas boom and brought many new industries. Glass companies like the Richardson Glass Works were lured by the inexpensive gas.

New manufacturers included eight window glass factories, two bottle, two chimney lamp, one light bulb, one novelty, and five for tableware. By 1887, Findlay became known as the “City of Light,” according to a historical marker erected in 1987 at the first field office of the Ohio Oil Company, which adopted the name Marathon Oil in 1962.

The Hancock Historical Museum in Findlay includes Great Karg Well exhibits less than two miles from the site of the famous well.

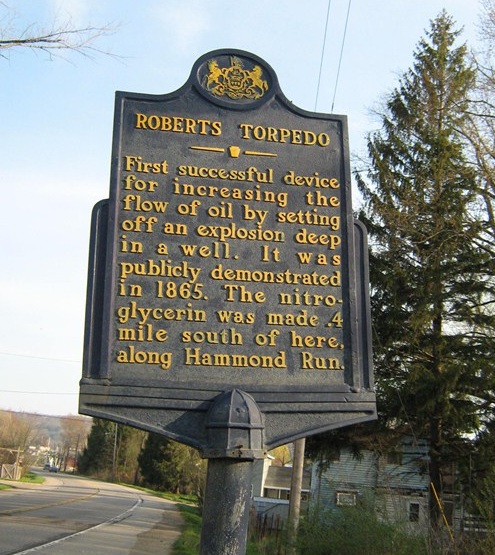

January 21, 1865 – Roberts Torpedo detonated, improving oil production

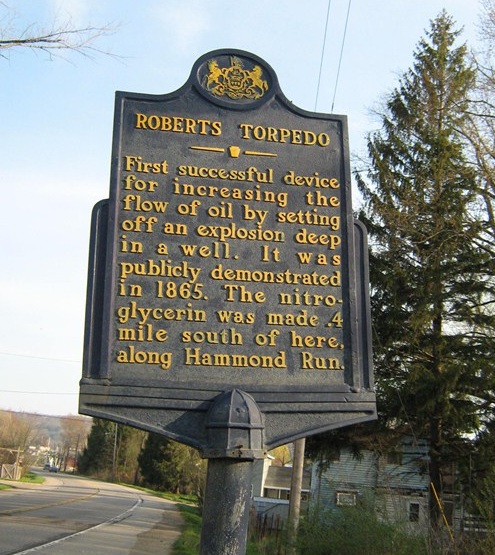

Civil War veteran Col. Edward A.L. Roberts (1829-1881) conducted his first experiment to increase oil production by using an explosive charge deep in the well. Roberts twice detonated eight pounds of black powder 465 feet deep in the bore of the “Ladies Well” on Watson’s Flats south of Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Civil War veteran Col. E.A.L. Roberts demonstrated his oil well “torpedo” south of Titusville, Pennsylvania.

The “shooting” of the well was a success, increasing daily production from a few barrels of oil to more than 40 barrels, according to Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine.

In April 1865, Roberts received the first of many patents for his “exploding torpedo.” The Titusville Morning Herald in 1866 reported, “Our attention has been called to a series of experiments that have been made in the wells of various localities by Col. Roberts, with his newly patented torpedo. The results have in many cases been astonishing.”

By 1870, Roberts’ torpedo technology using nitroglycerin became common in oilfields (see Shooters – A “Fracking” History).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Ranger, Images of America

(2000); Ranger, Images of America (2010); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2010); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Portrait in Oil: How Ohio Oil Company Grew to Become Marathon

(2009); Portrait in Oil: How Ohio Oil Company Grew to Become Marathon (1962); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America

(1962); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America (2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 12, 2024 | Petroleum History Almanac

The North Texas church once proclaimed as richest in America.

In the fall of 1917 near Ranger, Texas, the cotton-farming town of Merriman was inhabited by “ranchers, farmers, and businessmen struggling to survive an economic slump brought on by severe drought and boll weevil-ravaged cotton fields.”

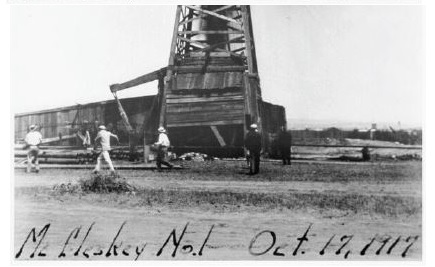

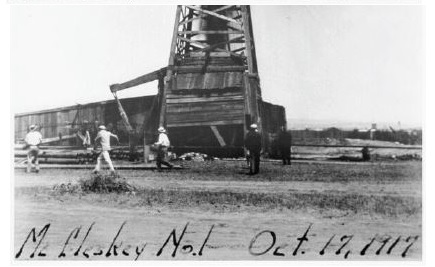

Everything changed in Eastland County when a wildcat well drilled by Texas & Pacific Coal Company struck oil at Ranger, four miles from Merriman. The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 well produced 1,600 barrels of oil a day.

McCleskey No. 1 cable-tool oil well, the “Roaring Ranger” gusher of 1917, brought an oil boom to Eastland County, Texas, about 100 miles west of Dallas.

The rush to acquire leases that followed the oilfield discovery became legendary among drilling booms, even for Texas, home of the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” on Spindletop Hill at Beaumont.

As drilling continued, yield of the Ranger oilfield led to peak production reaching more than 14 million barrels in 1919. Production from the “Roaring Ranger” well and its giant North Texas oilfield helped win World War I — with a British War Cabinet member declaring, “the Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Texas & Pacific Coal Company had taken a great risk by leasing acreage around Ranger, but the risk paid off when lease values soared. The exploration company added “oil” to its name, becoming the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

“So as we could not worship God on the former acre of ground, we decided to lease it and honor God with the product,” explained Merriman Baptist Church Deacon J.T. Falls. Photo courtesy Robert Vann, “Lone Star Bonanza, the Ranger Oil Boom of 1917-1923.”

The price of the oil company stock jumped from $30 a share to $1,250 a share as a host of landmen, “scanned the landscape to discover any fractions in these holdings. A little school and church, before too small to be seen, now looked like a sky scraper.”

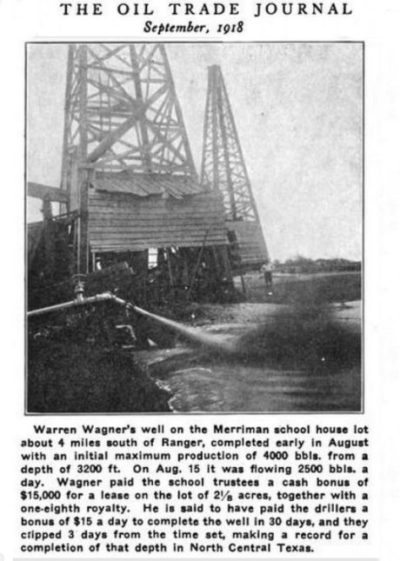

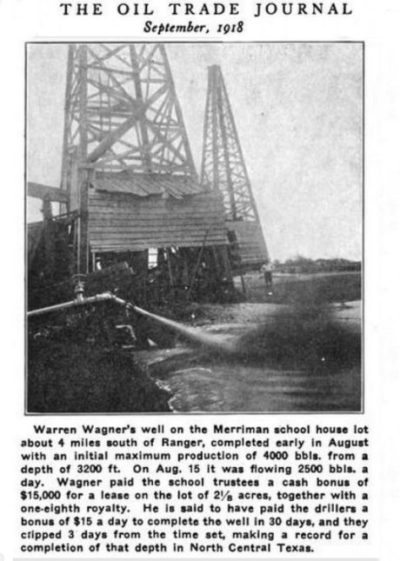

Warren Wagner, driller of the McCleskey discovery well, leased the local school lot and in August 1918 completed a well producing 2,500 barrels of oil a day. Leasing at Merriman Baptist Church proved to be a challenge.

Deacon J.T. Falls complained in February that the drilling boom’s oil wells, “ran us out, as all of the land around our acre was leased, producing wells being brought in so near the house we were compelled to abandon the church because of the gas fumes and noisy machinery.”

Falls added that, “So as we could not worship God on the former acre of ground, we decided to lease it and honor God with the product.”

Deacon J.T. Falls (second from left) was not amused when the Associated Press reported in 1919 that his church had refused a million dollars for the lease of the cemetery.

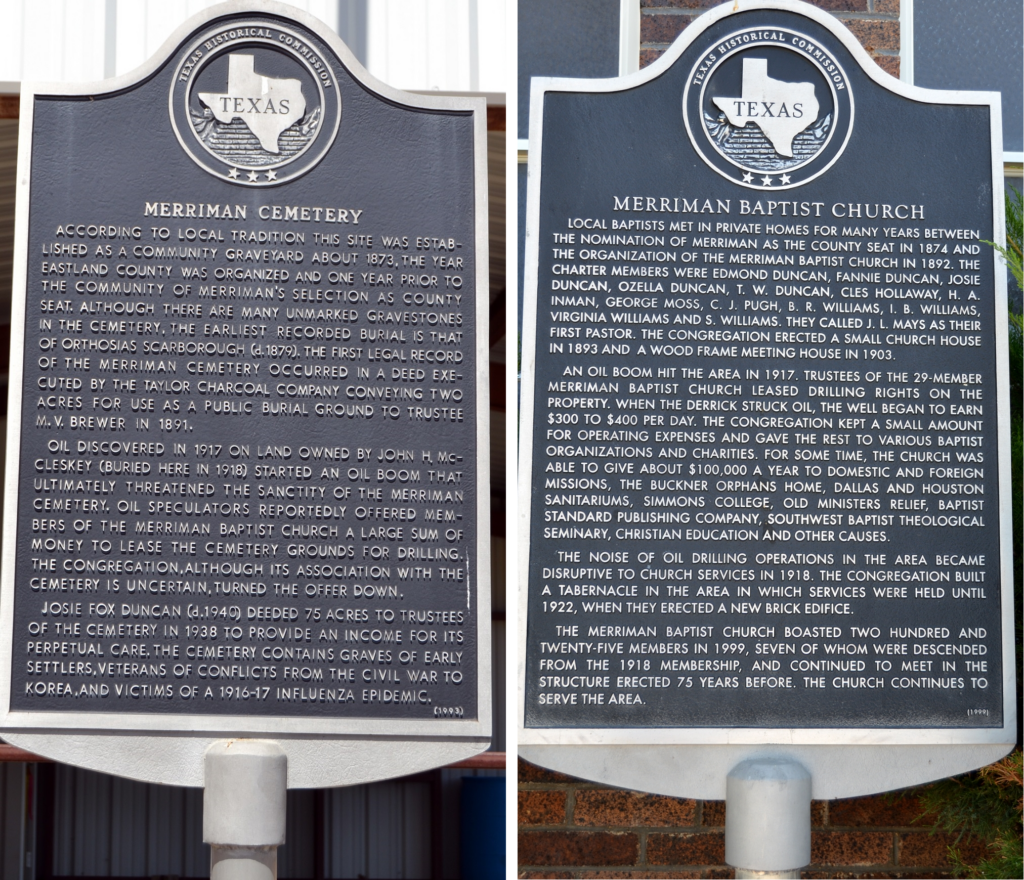

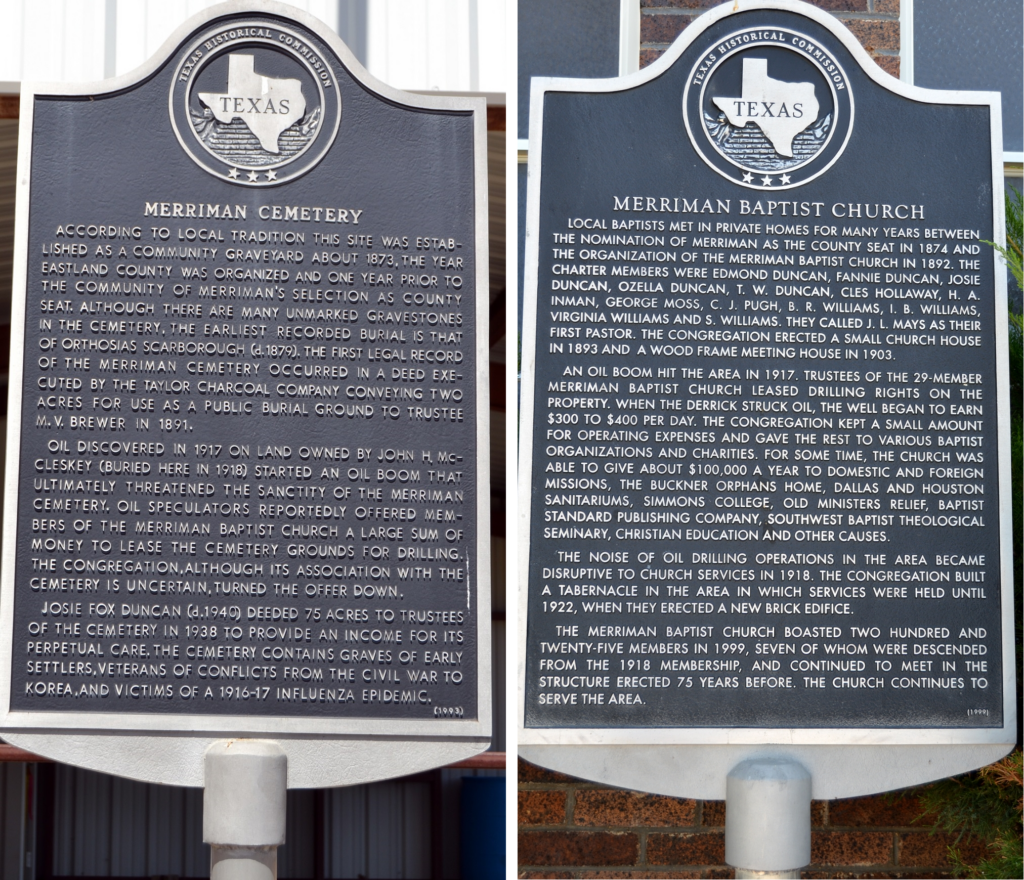

A Texas Historical Commission marker erected in 1999 described when the well on the church’s lease began producing oil, earning the congregation a royalty of between $300 and $400 a day. Merriman Baptist Church, “kept a small amount for operating expenses and gave the rest to various Baptist organizations and charities.”

However, drilling in the church graveyard was a different matter.

As oil production continued to soar in North Texas, the congregants of Merriman Baptist Church initially resisted one drilling drilling site. As a January 18, 1919, article in the New York Times noted in its headline, “CHURCH MADE RICH BY OIL; Refuses $1,000,000 for Right to Develop Wells in Graveyard.”

Respecting the Dead

At Merriman’s church cemetery, a less seen historical marker erected in 1993 explains the drilling boom’s fierce competition to find property without a well already on it: “Oil speculators reportedly offered members of the Merriman Baptist Church a large sum of money to lease the cemetery grounds for drilling.”

Near Ranger in Eastland County, Texas Historical Commission markers erected in 1993 (left) and 1999 explaining how members of the Merriman Baptist Church shared their wealth from petroleum royalties. Photos courtesy the Historical Marker Database.

When local newspapers reported the church had refused an offer of $1 million, the Associated Press picked it up and newspapers from New York to San Francisco ran the story. Literary Digest even featured, “the Texas Mammon of Righteousness” with a photograph of the “The Congregation That Refuses A Million.”

Deacon J.T. Falls was not amused. “A great many clippings have been sent to us from many secular papers to the effect that we as a church have refused a million dollars for the lease of the cemetery. We do not know how such a statement started,” the deacon opined.

“The cemetery does not belong to the church. It was here long before the church was. We could not lease it if we would and we would not if we could,” the cleric added.

“If any person’s or company’s heart has become so congealed as to want to drill for oil in this cemetery, they could not – for the dead could not sign a lease and no living person has any right to do so,” Falls proclaimed.

The church deacon concluded with an ominous admonition to potential drillers, “Those that have friends buried here have the right and the will to protect the graves and any person attempting to trespass will assume a great risk.”

A 1918 article noted a “Merriman school house” oil well drilled to 3,200 feet in record time for North Central Texas.

Roaring Ranger’s oil production dropped precipitously because of dwindling reservoir pressures brought on by unconstrained drilling. Many exploration and production companies failed (including fraudulent ones like Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company).

In the decades since the McCleskey No. 1 well, advancements in horizontal drilling technology have presented more legal challenges to mineral rights of the interred, according to Zack Callarman of Texas Wesleyan School of Law.

Callarman wrote an award-winning analysis of laws concerning drilling to extract oil and natural gas underneath cemeteries. “Seven Thousand Feet Under: Does Drilling Disturb the Dead? Or Does Drilling Underneath the Dead Disturb the Living?” was published in the Real Estate Law Journal in 2014.

Despite yet another North Texas oilfield discovery at Desdemona, by 1920 the Eastland County drilling boom was over. The faithful still gather at Merriman Baptist Church every Sunday.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2000); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2000); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History (2013); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2013); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: January 11, 2024. Original Published Date: January 18, 2019.

(2000); Ranger, Images of America

(2010); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009); Portrait in Oil: How Ohio Oil Company Grew to Become Marathon

(1962); Ohio Oil and Gas, Images of America

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.