This Week in Petroleum History, October 23 to October 29

October 23, 1908 – Salt Creek Well launches Wyoming Boom –

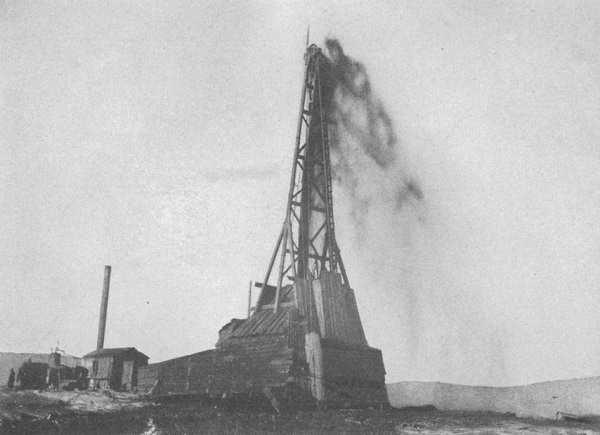

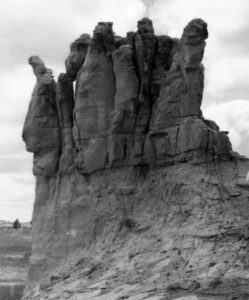

Wyoming’s first oil boom began when the Dutch company Petroleum Maatschappij Salt Creek completed its “Big Dutch” well about 40 miles north of Casper. Salt Creek’s potential had been known since the 1880s, but the area’s central geological salt dome received little attention until Italian geologist Cesare Porro recommended drilling there in 1906.

Five years earlier, a salt dome formation had revealed the giant Spindletop oilfield in Texas.

The “Big Dutch” No. 1 well, above, launched a Wyoming drilling boom in 1908. Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

The Oil Wells Drilling Syndicate, a British company, drilled the “Big Dutch” well, which produced 600 barrels of oil a day from 1,050 feet deep. By 1930, about one-fifth of all U.S. oil production came from the Salt Creek oilfield. Production continued with water-flooding technologies in the 1960s and the use of carbon dioxide injection beginning in 2004.

Learn more in First Wyoming Oil Wells.

October 23, 1948 – “Smart Pig” advances Pipeline Inspection

Northern Natural Gas Company recorded the first use of an X-ray machine for internal testing of petroleum pipeline welds. The company examined a 20-inch diameter pipe north of its Clifton, Kansas, compressor station. The device — today known as a “smart pig” — traveled up to 1,800 feet inside the pipe, imaging each weld.

A pipeline worker inspects a “smart pig.” Photo courtesy Pacific L.A. Marine Terminal.

As early as 1926, U.S. Navy researchers had investigated the use of gamma-ray radiation to detect flaws in welded steel. In 1944, Cormack Boucher patented a “radiographic apparatus” suitable for large pipelines. Modern inspection tools employ magnetic particle, ultrasonic, eddy current, and other methods to verify pipeline and weld integrity.

October 23, 1970 – LNG powers World Land Speed Record

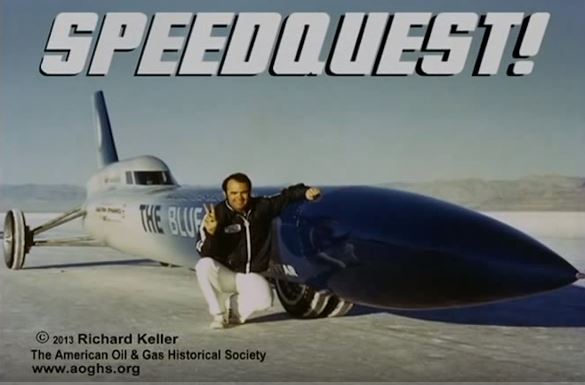

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) powered the Blue Flame to a new world land speed record of 630.388 miles per hour. A rocket motor combining LNG and hydrogen peroxide fueled the 38-foot, 4,950-pound Blue Flame, which set the record at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. The rocket motor could produce up to 22,000 pounds of thrust — about 58,000 horsepower.

In 1970, the Blue Flame achieved, “the greenest world land speed record set in the 20th century.”

Sponsored by the American Gas Association (AGA) and the Institute of Gas Technology, the Blue Flame design came from three Milwaukee, Wisconsin, automotive engineers: Dick Keller, Ray Dausman, and Pete Farnsworth. After building a record-setting rocket dragster in 1967 that got the attention of AGA executives, the men began designing a more ambitious vehicle.

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society interviewed Dick Keller in 2013 to produce a YouTube video using his 8mm home movies.

Interviewed for a 2013 video featuring his home movies, Keller explained how the growing environmental movement of the late 1960s, encouraged AGA “suits” to see value in educating consumers about natural gas as a fuel. In 2020. he published Speedquest: Inside the Blue Flam, his account of the last U.S. team to set the world land speed record. The Blue Flame, fueled by natural gas, remains “the greenest world land speed record set in the 20th century,” according to Keller,

Learn more in Blue Flame Natural Gas Rocket Car.

October 25, 1929 – Cabinet Member guilty in Teapot Dome Scandal

Albert B. Fall, appointed Interior Secretary in 1921 by President Warren G. Harding, was found guilty of accepting a bribe while in office, becoming the first cabinet official in U.S. history to be convicted of a felony. An executive order from President Harding had given Fall full control of the Naval Petroleum Reserves.

Wyoming’s Teapot Dome oilfield was named after Teapot Rock, seen here circa 1922 (the “spout” later fell off). Photo courtesy Casper College Western History Center.

Fall was found guilty of secretly leasing the Navy’s oil reserve lands to Harry Sinclair of Sinclair Oil Company and to Edward Doheny, discoverer of the Los Angeles oilfield.

The noncompetitive leases were awarded to Doheny’s Pan American Petroleum Company (reserves at Elk Hills and Buena Vista Hills, California), and Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Company (reserve at Teapot Dome, Wyoming). Fall received more than $400,000 from the two oil companies.

It emerged during In Senate hearings that cash was delivered to Secretary Fall in a Washington, D.C., hotel. He was convicted of taking a bribe, fined $100,000, and sentenced to one year in prison. Sinclair and Doheny were acquitted, but Sinclair spent six-and-a-half months in prison for contempt of court and the U.S. Senate.

October 26, 1970 – Joe Roughneck Statue dedicated in Texas

Texas Governor Preston Smith dedicated a “Joe Roughneck” memorial in Boonsville to mark the 20th anniversary of a giant natural gas field discovery there. In 1950, the Lone Star Gas Company Vaught No. 1 well had discovered the Boonsville field, which produced 2.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas over the next 20 years.

By 2001 the Boonsville field in East Texas reached production of 3.1 trillion cubic feet of gas from more than 3,500 wells.

“Joe Roughneck” in Boonsville, Texas. Photo, courtesy Mike Price.

“Joe Roughneck” began as a character in Lone Star Steel Company advertising in the 1950s. A bronze bust was awarded each year (until 2020) at the Chief Roughneck Award ceremony of the Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA). In addition to the Boonsville monument, Joe’s bust sits atop three different Texas oilfield monuments: Joinerville (1957), Conroe (1957) and Kilgore (1986).

Learn more in Meet Joe Roughneck.

October 27, 1763 – Birth of Pioneer American Geologist

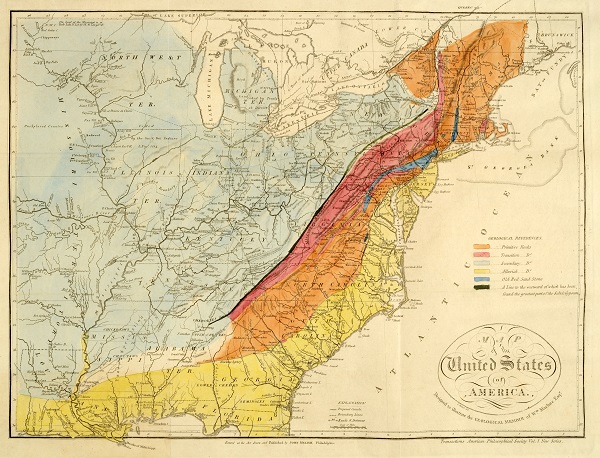

William Maclure, who would become a renowned American geologist and “stratigrapher,” was born in Ayr, Scotland. He created the earliest geological maps of North America in 1809 and later earned the title, “Father of American Geology.”

After settling in the United States in 1797, Maclure explored the eastern part of North America to prepare the first geological map of the United States. His travels from Maine to Georgia in 1808 resulted in the first geological map of the new United States.

“Map of the United States of America, Designed to Illustrate the Geological Memoir of Wm. Maclure, Esqr.” This 1818 version is more detailed than the first geological map he published in 1809. Image courtesy the Historic Maps Collection, Princeton Library.

“Here, in broad strokes, he identifies six different geological classes,” a Princeton geologist reported. “Note that the chain of the Appalachian Mountains is correctly labeled as containing the most primitive, or oldest, rock.”

In the 1850s, a chemist at Yale analyzed samples of Pennsylvania “rock oil” for refining into kerosene; his report led to the drilling of the first U.S. oil well in 1859 (also see Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology).

October 27, 1923 – Refining Company founded in Arkansas

Lion Oil Company was founded as a refining Company in El Dorado, Arkansas, by Texan Thomas Harry Barton. He earlier had organized the El Dorado Natural Gas Company and acquired a 2,000-barrel-a-day refinery in 1922.

Founded in 1923 in El Dorado, Arkansas, Lion Oil will operate about 2,000 service stations in the south in the 1950s. Photo courtesy Lion Oil.

Production from the nearby Smackover oilfield helped the Lion Oil Refining Company’s refining capacity grow to 10,000 barrels a day. By 1925, the company acquired oil wells producing 1.4 million barrels of oil.

A merger with Monsanto Chemical in 1955 brought the gradual disappearance of the once familiar “Beauregard Lion” logo. The company has continued to sell a variety of petroleum products, including gasoline, low-sulfur diesel fuel, solvents, propane and asphalt.

Learn more Arkansas history in Arkansas Oil and Gas Boom Towns.

October 28, 1926 – Yates Field discovered West of the Pecos in Texas

The 26,400-acre Yates oilfield was discovered in a remote area of Pecos County, Texas, in the Permian Basin. Drilled in 1926 with a $15,000 cable-tool rig, the Ira Yates 1-A produced 450 barrels of oil a day from almost 1,000 feet deep. Prior to the giant oilfield discovery, Ira Yates had struggled to keep his ranch on the northern border of the Chihuahua Desert.

“Drought and predators nearly did him in” noted one historian, until Yates convinced a San Angelo company to explore for oil west of the Pecos River. With the Pecos County well 30 miles from the nearest oil pipeline and a storage tank under construction, four more Yates wells yielded another 12,000 barrels of oil a day.

Ira Yates would receive an $18 million oil royalty check on his 67th birthday. Also see Santa Rita taps Permian Basin.

October 27, 1938 – DuPont names Petroleum Product “Nylon”

DuPont chemical company announced that “Nylon” would be the name of its newly invented synthetic fiber yarn made from petroleum. Discovered in 1935 by Wallace Carothers at a DuPont research facility, nylon is considered the first commercially successful synthetic polymer.

Nylon found widespread applications in consumer products, including toothbrushes, fishing lines, luggage and lingerie, or in special uses like surgical thread, parachutes, and pipes. Carothers would become known as the father of the science of man-made polymers (see Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer).

October 28, 1868 – Newspaper praises Explosive Technology

In Pennsylvania, the Titusville Morning Herald praised results of an explosive oilfield production technology, Civil War veteran Colonel E.A.L. Roberts’ patented nitroglycerin torpedo. “It would be superfluous, at this late day, to speak of the merits of the Roberts Torpedo,” the 1868 newspaper article explained.

“For the past three years, it has been a most successful operation, and has increased the production of oil in hundreds upon hundreds of oil wells to an extent which could hardly be overestimated” (see Shooters – a “Fracking” History).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Salt Creek Oil Field: Natrona County, Wyoming, 1912 (2017); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals

(1993); The Reluctant Rocketman: A Curious Journey in World Record Breaking

(2013); Speedquest: Inside the Blue Flame (2020); The Bradford Oil Refinery, Pennsylvania, Images of America

(2006); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982); Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain

(1984); The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World

(2015); Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.