by Bruce Wells | Jan 4, 2026 | Petroleum Pioneers

Oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover in the 1920s launched the Arkansas petroleum industry.

Arkansas oil wells of the 1920s created boom towns, established the state’s petroleum exploration and production industry, and boosted the career of a young wildcatter named Haroldson Lafayette Hunt.

The first Arkansas well that yielded “sufficient quantities of oil” was the Hunter No. 1 of April 16, 1920, in Ouachita County, according to the Arkansas Geological Survey. Natural gas was discovered a few days later in Union County by Constantine Oil and Refining Company.

Surrounded by 20 acres of woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in the Smackover oilfield preserves the state’s petroleum history seven miles north of equally historic El Dorado.

A January 1921 well drilled in the same Union County field at El Dorado marked the true beginning of commercial oil production in Arkansas. When the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well struck oil in 1921, the oilfield discovery soon catapulted the population of El Dorado from 4,000 to 25,000 people. The well, 15 miles north of the Louisiana border, was the state’s first commercial oil well.

“Twenty-two trains a day were soon running in and out of El Dorado,” noted the Arkansas Gazette. An excited state legislature announced plans for a special railway excursion for lawmakers to visit the oil well in Union County.

Meanwhile, Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt arrived from Texas with $50. He joined the crowd of lease traders and speculators at the Garrett Hotel, where fortunes were being made — and lost. Hunt launched his start as an independent oil and natural gas producer during the El Dorado drilling boom.

Some locals said it was his expertise at the poker table that earned him enough to afford a one-half acre parcel lease where his Hunt-Pickering No. 1 well produced some oil but ultimately proved unprofitable.

Hunt persevered and within four years acquired substantial El Dorado and Smackover oilfield holdings. By 1925, he was a successful 36-year-old oilman with his wife Lyda and three young children living in a three-story El Dorado home. He would significantly add to his oilfield successes a decade later in Kilgore, Texas (learn more in East Texas Oilfield Discovery).

Giant Oilfield at El Dorado

Located on a hill a little over a mile southwest of El Dorado, the derrick was visible from the town, according to historians A.R. and R.B. Buckalew. They write that three “gassers” had been completed in the general vicinity but did not produce in commercial quantities.

There was no market for natural gas at the time, the authors explained in their 1974 book, The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924.

The Garrett Hotel, where H.L. Hunt checked in with 50 borrowed dollars and launched his long career as a successful independent oil producer.

Yet Dr. Samuel T. Busey was convinced “there was oil down there somewhere.”

The authors added, “Among those who gambled their savings with Busey at this time were Wong Hing, also called Charles Louis, a Chinese laundry man, and Ike Felsenthal, whose family had created a community in southeast Union County in earlier years.”

With no oil production nearby, investing in the “wildcat” well was a leap of faith. Chal Daniels, who was overseeing drilling operations for Busey, contributed the hefty sum of $1,000. On January 10, 1921, the well had been drilled to 2,233 feet and reached the Nacatoch Sand. A small crowd of onlookers and the drilling crew — after moving a safe distance away — watched and listened.

“The spectators, among them Dr. Busey, watched with an air of expectancy,” noted the historians. “Drilling had ceased and bailing operations had begun to try to bring in the well. At about 4:30 p.m., as the bailer was being lifted from its sixth trip into the deep hole, a rumble from deep in the well was heard.”

The rumbling grew in intensity, “shaking the derrick and the very ground on which it stood as if an earthquake were passing,” the authors report. “Suddenly, with a deafening roar, ‘a thick black column’ of gas and oil and water shot out of the well,” they added.

The gusher blew through the derrick and “bursts into a black mushroom” cloud against the January sky. The Busey No. 1 well produced 15,000,000 to 35,000,000 cubic feet of gas and from 3,000 to 10,000 barrels of oil and water a day.

Petroleum brings Prosperity

Thanks to the El Dorado discovery, the first Arkansas petroleum boom was on. By 1922, there were 900 producing wells in the state.

Civic leaders raised funds to preserve El Dorado’s historic downtown — and add an Oil Heritage Park at 101 East Main Street.

“Three months after the Busey well came in, work was underway on an amusement park located three blocks from the town that would include a swimming pool, picnic grounds, rides and concessions,” noted the Union County Sheriff’s Office. “Culture was not forgotten as an old cotton shed in the center of town near the railroad tracks was converted to an auditorium.”

The 68-square-mile field will lead U.S. oil output in 1925 — with production reaching 70 million barrels. “It was a scene never again to be equaled in El Dorado’s history, nor would the town and its people ever be the same again,” the authors concluded. “Union County’s dream of oil had come true.”

In 2002, El Dorado gathered 40 local artists to paint 55 oil drums donated by the local Murphy Oil Company. Preserving the town’s historic assets, including boom-era buildings, remains a major goal of the local group, Main Street El Dorado, which was the “2009 Great American Main Street Award Winner” of the National Trust Main Street Center.

Second Oil Boom: Discovery at Smackover

Prior to the January 1921 El Dorado discovery, the region’s economy relied almost exclusively on the cotton and timber industries “that thrived in the vast virgin forests of southern Arkansas.”

Petroleum wealth helped Smackover, Arkansas, incorporate in 1922.

Six months after the Busey-Armgstrong No. 1 well, another giant oilfield discovery 12 miles north will bring national attention — and lead to the incorporation of Smackover. A small agricultural and sawmill community with a population of 131, Smackover had been settled by French fur trappers in 1844. They called the area “Sumac-Couvert,” meaning covered with sumac or shumate bushes.

According to historian Don Lambert, by 1908 Sidney Umsted operated a large sawmill and logging venture two miles north of town. He believed that oil lay beneath the surface. “On July 1, 1922, Umsted’s wildcat well (Richardson No. 1) produced a gusher from a depth of 2,066 feet,” Lambert reported.

“Within six months, 1,000 wells had been drilled, with a success rate of ninety-two percent. The little town had increased from a mere ninety to 25,000, and its uncommon name would quickly attain national attention,” added Lambert.

Roughnecks photographed following the July 1, 1922, discovery of the Smackover (Richardson) field in Union County. Courtesy of the Southwest Arkansas Regional Archives.

The oil-producing area of the Smackover field covered more than 25,000 acres. By 1925, it had become the largest-producing oil site in the world. The field will produce 583 million barrels of oil by 2001.

Opened in 1986, the Arkansas Natural Resources Museum educates visitors in the heart of the historic Smackover oilfield. Exhibits explain how the Busey No. 1 well near El Dorado “blew in with a gusty fury” in January 1921.

The museum includes a five-acre Oilfield Park with operating examples of early and modern oil-producing technologies. They can be found one mile south of the once petroleum-rich town of Smackover, which has celebrated its petroleum heritage with an “Oil Town Festival” every June.

Abundant natural gas in the Fayetteville shale formation brought more drilling to Arkansas.

With more than 46,800 wells drilled between 1925 and 2023, about one-third of the 75 Arkansas counties have produced oil and/or natural gas, reported Mineralsanswers.com in July 2024.

Southern Arkansas also is considered among the most prolific lithium resources of its type in North America, according to ExxonMobil, which in 2023 acquired the rights to 120,000 gross acres of the Smackover formation.

Fayetteville Shale

Thanks to advances in drilling technologies combined with hydraulic fracturing, the Fayetteville Shale — a 50-mile-wide formation across central Arkansas — has added vast natural gas reserves while creating a new petroleum boom for the state.

Unlike traditional fields containing hydrocarbons in porous formations, shale holds natural gas in a fine-grained rock or “tight sands.” Until the 1990s, drilling in most shale formations was not considered profitable for production.

Surrounded by 20 acres of lush woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources collects and exhibits southern Arkansas petroleum — along with the history of brine drilling and the salt industry. It also has documented the social and economic histories that accompanied the 1920s oil boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924 (1974); The Three Families of H. L. Hunt (1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Arkansas Oil Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/arkansas-oil-and-gas-boom-towns. Last Updated: January 3, 2026. Original Published Date: April 21, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

September 30, 2006 – Roughnecks Statue dedicated at Signal Hill –

A bronze Tribute to the Roughnecks statue was dedicated near the Alamitos No. 1 well, which in 1921 revealed California’s prolific Long Beach oilfield 20 miles south of Los Angeles.

Signal Hill once had so many derricks people called it Porcupine Hill. The city of Long Beach is visible in the distance from the “Tribute to the Roughnecks” statue by Cindy Jackson.

The statue by Cindy Jackson has since commemorated the Signal Hill Oil Boom, serving as “a tribute to the petroleum pioneers for their success here, a success which has, by aiding in the growth and expansion of the petroleum industry, contributed so much to the welfare of mankind.”

October 1, 1908 – Ford Motor Company produces First Model T

The first production Ford Model T rolled off the assembly line in Detroit. Between 1908 and 1927, Ford built about 15 million more, each fueled by inexpensive gasoline. The popularity of the Model T was timely for the U.S. petroleum industry, which faced falling demand for kerosene as consumers switched to electric lighting.

Ford Model T tires were white until 1910, when the petroleum product carbon black was added to improve durability.

New major oilfield discoveries, especially the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, Texas, helped meet growing demand for what had been a refining byproduct, gasoline.

October 1, 1920 – Gonzaullas becomes a Texas Ranger

Manuel T. Gonzaullas joined the Texas Rangers — and rowdy Texas boom towns would never be the same. He soon became known as “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas.

“World’s Richest Acre Park, where once stood the world’s greatest concentration of oil wells.” A street scene in Kilgore, Texas, depicting steel derricks behind stores, is one of many by Russell Lee (1903-1986) preserved by the Library of Congress.

In East Texas, when the streets of downtown Kilgore sprouted oil derricks, the population grew from 700 to 10,000 in two weeks. With Depression-era petroleum discoveries multiplying, oil boom towns often attracted criminals. Riding a black stallion named Tony and sporting two pearl-handled .45 pistols, Gonzaullas soon earned a reputation for strictly enforcing the law.

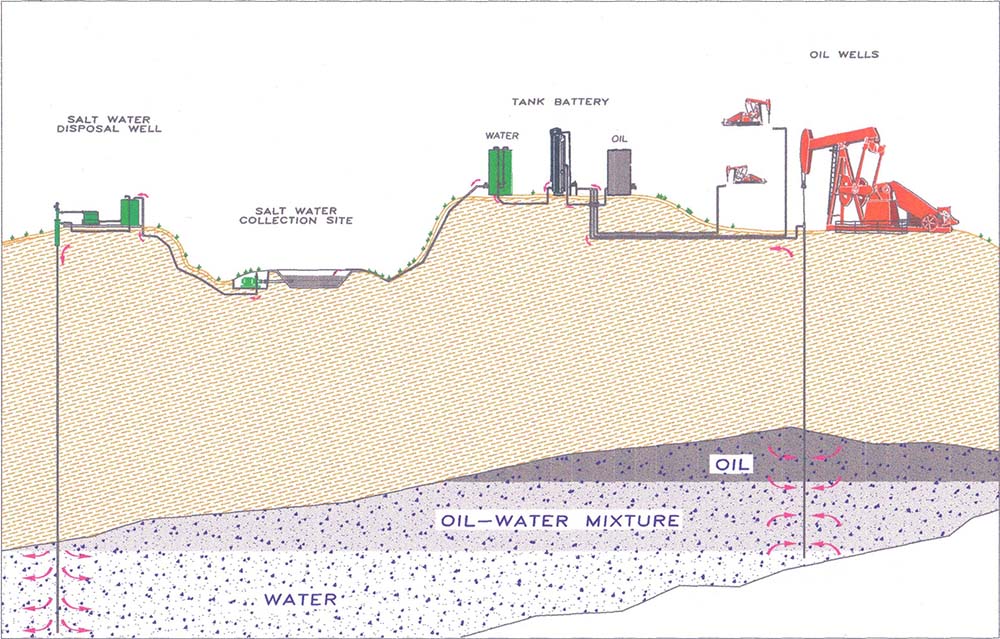

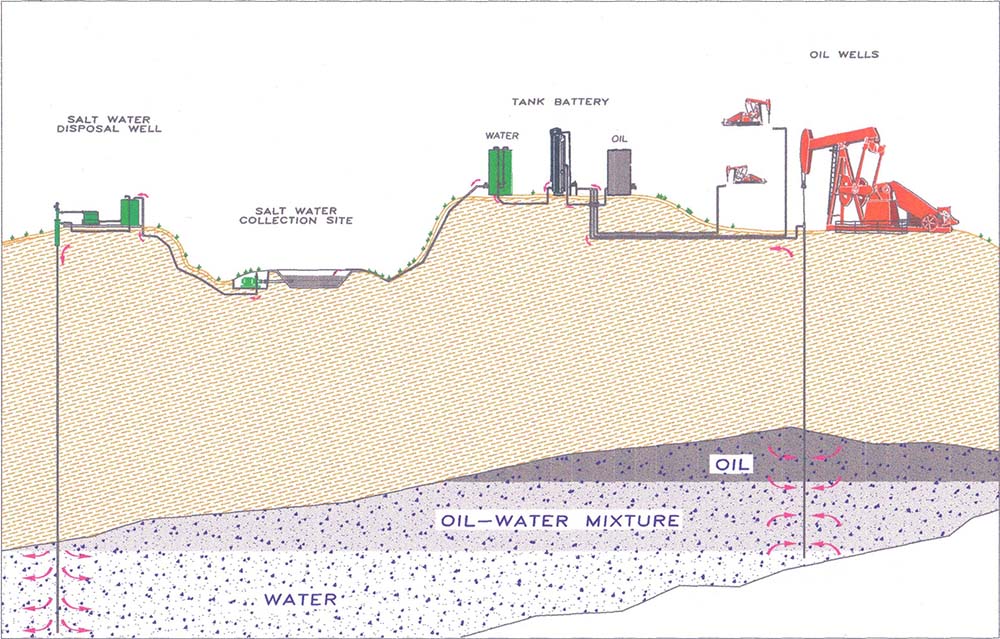

October 1, 1942 – Water Injection begins in East Texas

The East Texas Salt Water Disposal Company drilled the first saltwater injection well in the 12-year-old East Texas oilfield near the towns of Tyler, Longview, and Kilgore. As early as 1929, the Federal Bureau of Mines had determined injecting recovered saltwater into formations could increase reservoir pressures and oil production.

Saltwater injection wells improve oil production and keep marginal East Texas wells viable. Illustration courtesy East Texas Salt Water Disposal Company.

The Texas Railroad Commission established the saltwater disposal company as a public utility to operate in the oilfield. The company treated and reinjected about 1.5 billion barrels of saltwater in its first 13 years, prompting the commission to proclaim saltwater injection as the “greatest oil conservation project in history.”

October 2, 1919 – Future “Mr. Tulsa” incorporates Skelly Oil

Skelly Oil Company incorporated in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with founder William Grove Skelly as president. He had been born in 1878 in Erie, Pennsylvania, where his father hauled oilfield equipment in a horse-drawn wagon.

Born near Pennsylvania oilfields, William Skelly founded Skelly Oil Company in 1919 — and led an international petroleum exposition for 32 years, helping to make Tulsa the “Oil Capital of the World.”

Skelly’s success in the El Dorado oilfield east of Wichita, Kansas, helped him launch Skelly Oil and other ventures, including Midland Refining Company, which he founded in 1917. As Tulsa promoted itself as “Oil Capital of the World,” Skelly became known as “Mr. Tulsa.”

Skelly served as president of Tulsa’s famous International Petroleum Exposition for 32 years until his death in 1957.

October 3, 1930 – East Texas Oilfield discovered on Widow’s Farm

Ninety-five years ago, with a crowd of more than 4,000 expectant landowners, leaseholders, creditors, and others watching, the Daisy Bradford No. 3 wildcat well was successfully shot with nitroglycerin near Kilgore, Texas.

Spectators gathered on the widow Daisy Bradford’s farm near Kilgore, Texas, to watch the October 3, 1930, “shooting” of the discovery well of what proved to be the largest oilfield in the lower 48 states. Photo courtesy Jack Elder, The Glory Days.

“All of East Texas waited expectantly while Columbus ‘Dad’ Joiner inched his way toward oil,” explained historian Jack Elder in 1986. “Thousands crowded their way to the site of Daisy Bradford No. 3, hoping to be there when and if oil gushed from the well to wash away the misery of the Great Depression.”

Geologists were stunned when it became apparent the remote wildcat well on the widow Daisy Bradford’s farm — along with two other wells far to the north — were part of the same oil-producing formation (the Woodbine) that encompassed more than 140,000 acres. The “Black Giant” would produce billions of barrels of oil in coming decades.

Learn more in East Texas Oilfield Discovery.

October 3, 1980 – Museum opens in East Texas Oilfield

Fifty years after the discovery of the East Texas oilfield, the East Texas Oil Museum at Kilgore College opened as “a tribute to the independent oil producers and wildcatters, the men and women who dared to dream as they pursued the fruits of free enterprise.”

The East Texas Oil Museum since 1980 has hosted events and maintained exhibits preserving the “Black Giant” oilfield discovered during the Great Depression. Photos by Bruce Wells.

Established with funding from the Hunt Oil Company, the museum at Kilgore College recreated a 1930s boom town atmosphere. The museum, which is hosting special events on its 45th birthday, maintains a database that offers keyword search and advanced search options — along with a “random Images” button to browse photography from a wide assortment of online records.

October 4, 1866 – Oil Fever spreads to Allegheny River Valley

Just 15 miles east of Titusville, Pennsylvania, site of the first U.S. oil well, an oilfield discovery at Triumph Hill sparked another wild rush of speculators and new drilling. America’s petroleum industry was barely seven years old when wooden cable-tool derricks and engine houses replaced hemlock trees along the Allegheny River.

October 4, 1901 – Drake Memorial dedicated in Pennsylvania

More than 2,500 people, including his widow, Laura Dowd Drake, attended the unveiling of a monument to the “father of the petroleum industry,” Edwin L. Drake, who had died in relative obscurity in 1880. Standard Oil Company executive Henry Rogers commissioned the marble, semi-circle memorial in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Unveiling of the Drake Monument in Titusville, Pennsylvania, on October 4,1901. Thousands attended the dedication in Woodlawn Cemetery. Photo by John Mather courtesy Drake Well Museum.

The monument, which includes a bronze statue by Charles Henry Niehaus, was dedicated in Woodlawn Cemetery. Learn more by visiting Titusville’s Drake Well Museum and Park.

October 5, 1915 – Science of Petroleum Geology reveals Oilfield

Using the new earth science of petroleum geology for finding oil led to the discovery of the giant Mid-Continent field in central Kansas. Drilled by Wichita Natural Gas Company, a subsidiary of Cities Service Company, the well revealed the 34-square-mile El Dorado oilfield.

The Stapleton No. 1 well in 1915 revealed the El Dorado, Kansas, oilfield, among the largest in the world. By 1919, Butler County had more than 1,800 producing oil wells. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“Pioneers named El Dorado, Kansas, in 1857 for the beauty of the site and the promise of future riches, but not until 58 years later was black rather than mythical yellow gold discovered when the Stapleton No. 1 oil well came in on October 5, 1915,” explained geologist Lawrence Skelton in 1997.

The Stapleton No. 1 well east of Wichita initially found oil at a depth of 600 feet before being deepened to 2,500 feet to produce 110 barrels of oil a day from the Wilcox sands. Natural gas discoveries one year earlier at nearby Augusta had prompted El Dorado civic leaders to seek their own geological study of Mid-Continent fields.

The Stapleton No. 1 well and the Kansas Oil Museum preserve a 1915 oil discovery. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Kansas Oil Museum preserves the state’s petroleum heritage with historic oilfield equipment displayed on 10 acres east of the city. Museum exhibits describe how lessons from the El Dorado field helped launch petroleum geology as a profession while establishing El Dorado as a center for refining.

Learn more in the Kansas Oil Boom.

October 5, 1958 – Water Park opens in West Texas for One Day

A water park inside a Depression-era experimental concrete oil tank opened to the public in West Texas. The day’s festivities at Monahans attracted swimmers, boaters, anglers, and even water skiers to the massive, manmade lake — before leaks at the seams forced it to close the next day.

The Million Barrel Museum’s site was originally built to store Permian Basin oil. For scale, note the railroad car and caboose exhibit at upper right.

A local couple had attempted to find a good use for the 525-foot by 422-foot “million barrel reservoir” once covered by a redwood dome roof. The concrete tank had been completed in 1928 by Shell Oil due to a lack of pipelines for Permian Basin oil. Shell stopped using the tank because the company could not prevent oil from leaking at the seams.

Learn more in Million Barrel Museum.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Signal Hill, California – Images of America (2006); From Here to Obscurity: An Illustrated History of the Model T Ford, 1909 – 1927

(2006); From Here to Obscurity: An Illustrated History of the Model T Ford, 1909 – 1927 (1971); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems

(1971); Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems (1984); An adventure called Skelly: A history of Skelly Oil Company through fifty years, 1919-1969 (1970); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skullduggery & Trivia

(1984); An adventure called Skelly: A history of Skelly Oil Company through fifty years, 1919-1969 (1970); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skullduggery & Trivia (2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976

(2008); The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976 (1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

Prior to becoming an aspiring Kansas oilman, William Seyler wrote a book admonishing others about speculating in the petroleum industry. Then he started his own oil company.

Seyler was a self-proclaimed capitalist and investment expert who in 1919 published Danger Signals – A Key to Investing Money to Make Money.

His book (today available free online) offered several chapters about America’s rapidly expanding petroleum industry, including chapter 12, “Oil Land Get-Rich-Quick Schemes.”

Seyler advised potential investors to be wary. “The alluring possibilities of the oil business is, at this very writing, causing so many inexperienced men to engage in the promotion of wild-cat oil companies that haven’t the remotest chance to succeed,” he proclaimed. “Experience and constant practice alone make experts in judging the soundness of stocks and securities; of this there is no doubt.”

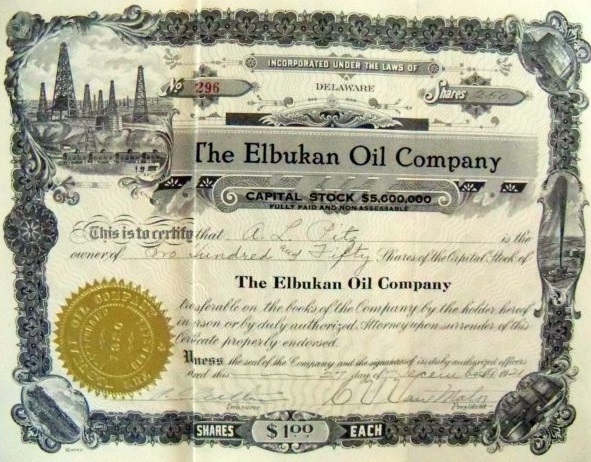

Within a year of publishing his book of investment advice, Seyler incorporated Elbukan Oil Company in Delaware (June 5, 1920). He began operations in El Dorado, Kansas, where the Stapleton No. 1 well of 1915 had launched a major Kansas Oil Boom.

His company was initially capitalized at $750,000 with par value assigned at $1 per share. But by March 1921 Elbukan Oil had increased its capital stock to $1.5 million to fund acquisition of more properties in the prolific Mid-Continent field.

The company successfully completed its Millheisler No. 5 well, which produced 100 barrels of oil northeast of El Dorado. Although production declined to 50 barrels a day, the success enabled the company to drill another well, the Millheisler No. 6, on the same 40-acre lease.

By December 31, 1921, Elbukan Oil Company had sold approximately $1.6 million of stock to investors nationwide, apparently including a large number from Wisconsin.

Seemingly prospering, the company owned a number of leases and pipelines in Kansas and Oklahoma. By 1923 it was producing and selling oil and natural gas. Then questions were raised about its accounting practices.

Elbukan Oil was prohibited from selling its stock in Wisconsin and Indiana, “as a result of continued delays by the Seyler company in presenting the semiannual audit of the financial conditions require by the state commission of all companies selling stock.”

The company’s difficulties compounded when it was alleged in court that Seyler had set up his company’s $120,000 purchase of a well valued at only $6,000. The deal included Elbukan Oil paying him personally $42,500 in cash and stock.

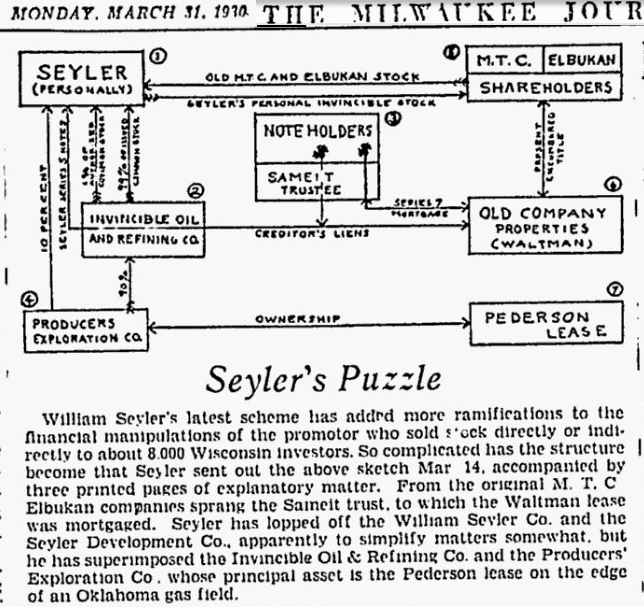

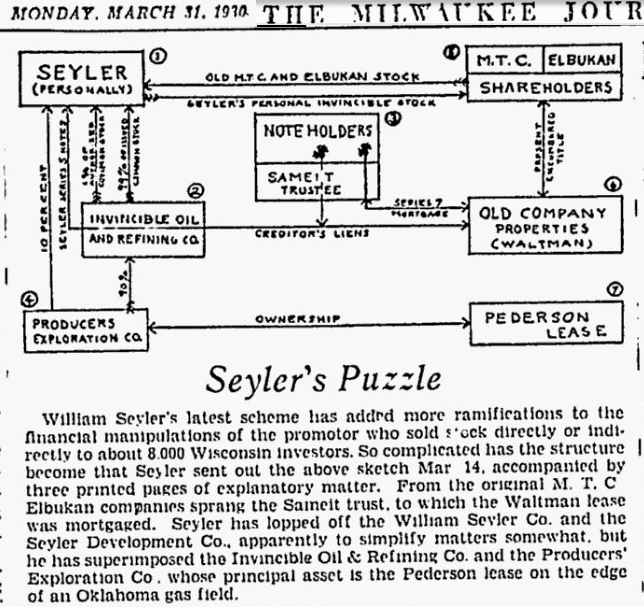

The U.S. District Court ultimately appointed receivers to manage Elbukan Oil assets as extended litigation followed. Undeterred, Seyler returned in 1930 – only to have the Milwaukee Journal report expose “William Seyler’s latest scheme.”

The Wisconsin newspaper illustrated Seyler’s intricate structure of company ownership, liens, properties, mortgages and stockholders. “Seyler’s Puzzle” appeared in a March 31, 1930, article.

Although Elbukan Oil Company stock was worthless by 1932, Seyler was not finished. He returned to Wisconsin investors one last time five years later, according to the Milwaukee Journal.

“Seyler, Oil Promoter, Again is Active Here,” the newspaper noted on April 15, 1937, adding that the investment adviser turned oilman was back “with a brand new scheme.” Editors again cautioned readers: “State authorities say Seyler and his many associates at one time took in $3,200,000 from about 9,000 Wisconsin residents.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of other companies and attempts to join highly speculative petroleum exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

___________________________________________________________________________________

Please support the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and this website with a donation.

(1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.