by Bruce Wells | Oct 10, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

After months of hard drilling, a North Texas oil well roared in at Ranger in 1917.

As World War I continued in Europe, the “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery well of October 1917 in Eastland County, Texas, revealed a giant oilfield that would help fuel the Allied victory.

Residents of the town of Ranger — about halfway between Dallas and Abilene — had been eager to find oil, especially after reading newspaper accounts of an oilfield discovery on April Fool’s Day 1911 at Electra in neighboring Wichita County. A decade earlier in southeastern Texas, the “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill had launched the modern U.S. petroleum industry.

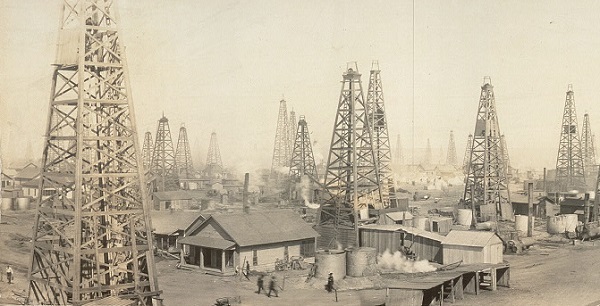

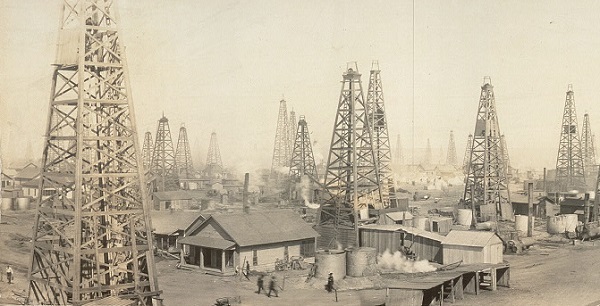

Detail of a photo showing “Roaring Ranger,” the McCleskey No. 1 well, erupting oil in Eastland County and launching a North Texas drilling boom. Photo courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

As the area’s cotton farmers struggled with severe drought, Ranger town officials hoped to strike “black gold.” For help, they turned to William K. Gordon, vice president of the Texas and Pacific Coal Company in Thurber. His company mined shale from hills near Thurber.

“Roaring Ranger”

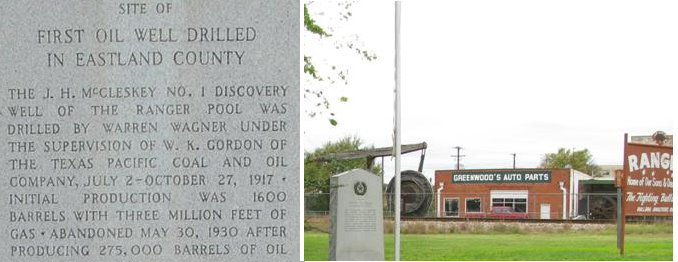

After one failed test with a shallow well, Gordon agreed to drill the second attempt up to 3,500 feet deep. Drilling with basic cable-tool technology, Gordon and contractor Warren Wagner spudded the exploratory wildcat well on July 2, 1917, on the McCleskey farm, two miles south of Ranger.

After more than three months of drilling, the J.H. McCleskey No. 1 well erupted a geyser of oil on October 17, 1917, from a depth of 3,432 feet.

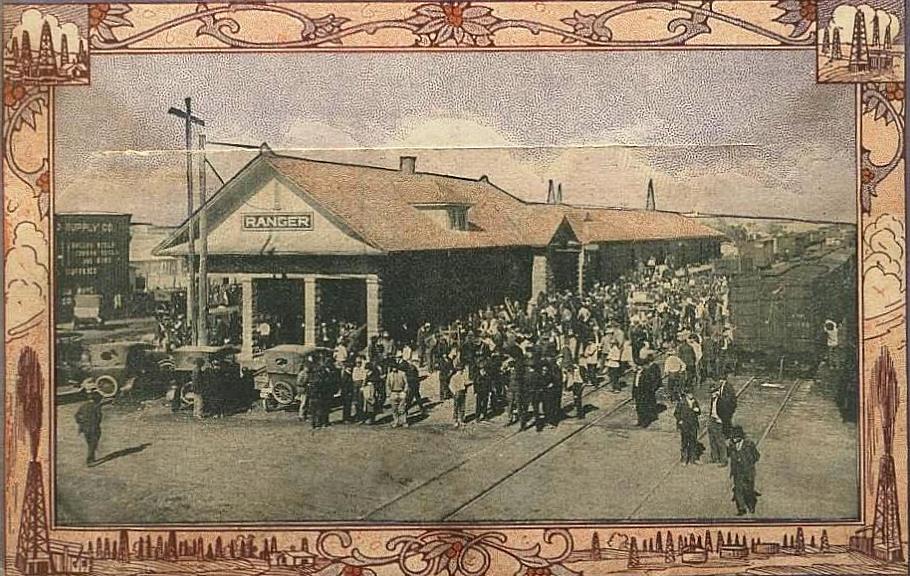

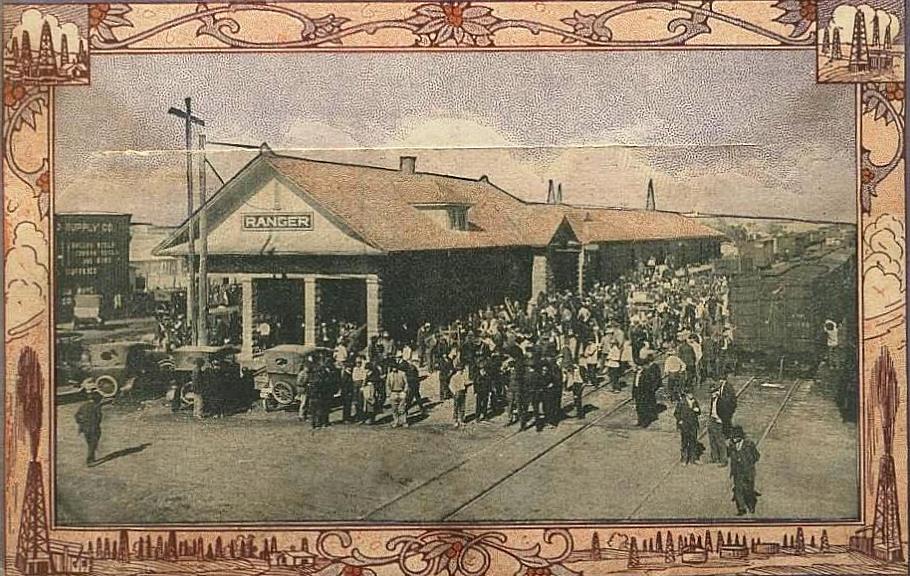

Following the October 1917 oilfield discovery, the Texas and Pacific Railroad transported people, equipment, and petroleum in and out of Ranger. A circa 1920 postcard shows the depot, future home of the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum.

When completed, “Roaring Ranger” initially produced 1,600 barrels of high-gravity oil per day. Later oil gushers yielded up to 10,000 barrels of oil daily. Within 20 months, Texas and Pacific Coal Company stock jumped from $30 a share to $1,250 a share.

The suddenly wealthy petroleum exploration company added “oil” to its name, reorganizing as the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

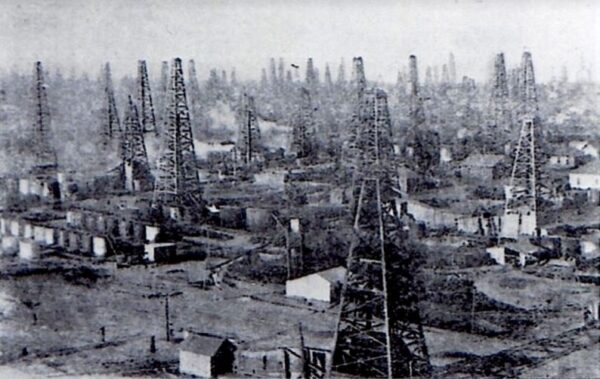

“Almost overnight, you couldn’t even see the homes for the derricks,” said Ranger historian Jeane B. Pruett. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Eastland County oil discoveries brought economic booms to Ranger, Cisco, and Desdemona — today a ghost town. As leasing intensified in and around Desdemona by 1918, convincing the congregation of a Baptist Church to allow drilling proved to be a challenge (see Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church).

Among the veterans visiting booming Eastland County after the war was a young Conrad Hilton, who visited Cisco intending to buy a bank. When he witnessed the long line of roughnecks waiting for a room at the Mobley Hotel, he decided to buy the hotel (see Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel).

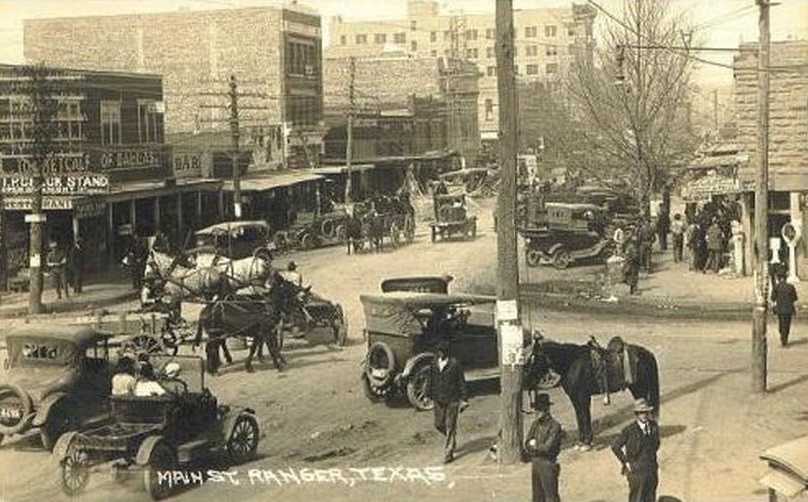

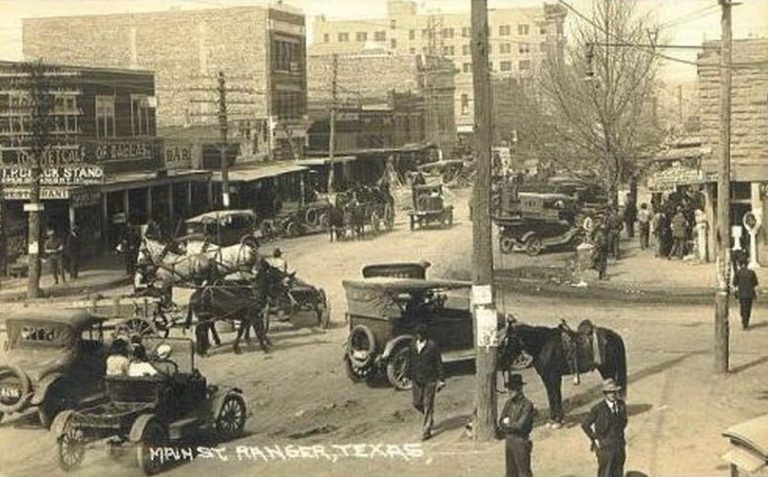

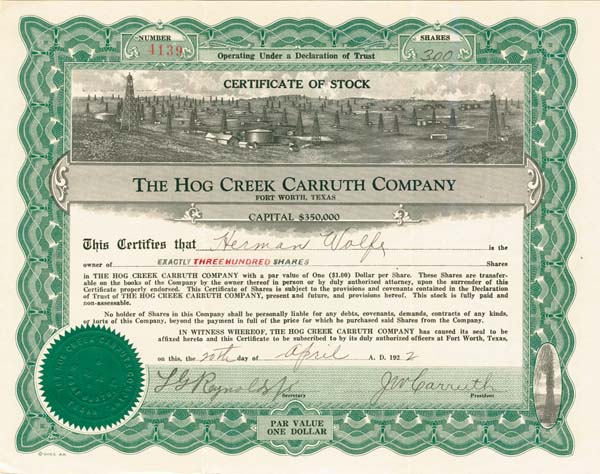

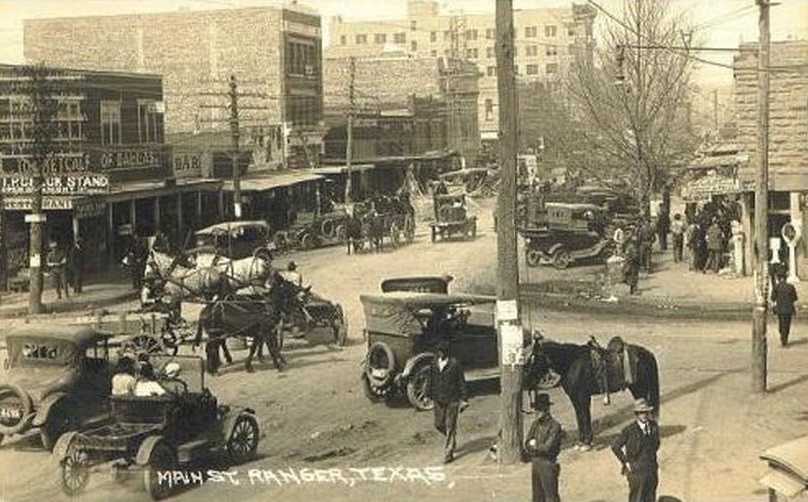

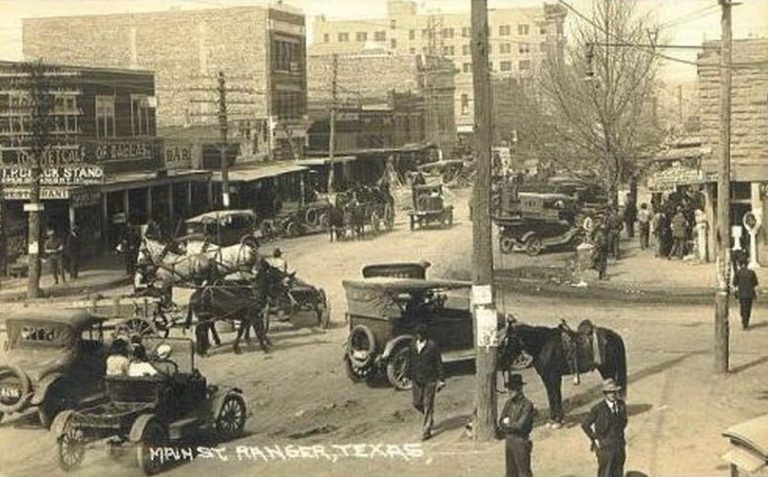

The Abilene Reporter-News reported Ranger’s population swelled from less than 1,000 to more than 30,000 — mostly men. Opportunities for illicit financial gain also attracted notorious oilfield hucksters like J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth (see Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever).

The 2016 Roaring Ranger Day Parade took place on the 99th birthday of the town’s famous oil gusher. Photo courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

Eastland County’s drilling and production boom grew rapidly as petroleum companies rushed to Ranger to develop the giant oilfield, according to historian Damon Sasser.

By 1919, the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company had 22 oil wells — and eight refineries open or under construction. More freight was unloaded in Ranger by the railroad than at any other place upon its line, including stations in Fort Worth, Dallas and New Orleans.

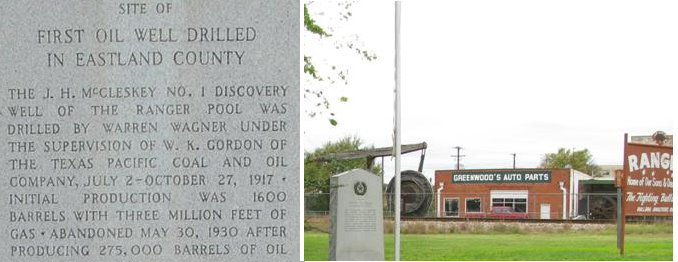

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a mammoth oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The flood of people also brought Texas Rangers to the boom town, which had begun as a Ranger camp in the 1870s. When Ranger jails overflowed, the lawmen handcuffed prisoners to telephone poles.

Meanwhile, independent and major exploration companies discovered nearby oilfields, including the Parsons, Sinclair-Earnest, and Lake Sand fields.

Photos courtesy Sarah Reveley and Barclay Gibson, who have photographed Texas Historical Commission markers and helped locate hundreds of historic sites from Louisiana to New Mexico.

Production from the Breckenridge oilfield in neighboring Stephens County was 10 million barrels of oil by 1919. It peaked at more than 31 million barrels of oil in 1921.

“Wave of Oil” wins WW I

“Roaring Ranger” and the region’s production had proved essential to the Allied victory in World War I. When the armistice was signed in 1918, a member of the British War Cabinet declared, “The Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Ranger’s boom ended in the early 1920s when excess oil production caused wells to fail, but the discoveries confirmed the existence of a large petroleum-producing region, the Mid-Continent, with hundreds of oilfields stretching from Texas into Oklahoma and Kansas.

Eastland County oil discoveries, which began with the “Roaring Ranger” well of 1917, brought economic booms to Ranger, Cisco, and Desdemona. Photo courtesy Jeane B. Pruett and the family of W.K. Gordon Jr.

Established by the Ranger chamber of commerce in 1982, the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum — inside the original Texas and Pacific Railway’s depot — exhibits drilling equipment, historic photos and a vintage cable-tool rig.

Ranger residents annually celebrate their 1917 oilfield discovery with a festival and parade down Main Street. When the parade crosses the historic train depot’s tracks, participants pass a small, gray granite marker dedicated to the “First Oil Well Drilled in Eastland County.”

The 1936 Texas Centennial marker remains “a highly cherished monument that Ranger should be very proud of,” according to Eastland County resident Sarah Reveley, who documented many Texas Historical Commission sites.

Other dedicated advocates for preserving local petroleum history included Jeane B. Pruett (1935-2022), a longtime friend of the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Ranger, Images of America (2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Roaring Ranger wins WWI.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/roaring-ranger-wins-wwi. Last Updated: October 10, 2025. Original Published Date: July 1, 2004.

by Bruce Wells | May 15, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Widely publicized drilling booms attracted investors seeking “black gold” riches — real or imagined.

Exaggerated, questionable, and sometimes fraudulent claims by shady business ventures seeking investors grew in the years following World War I. As the Great Depression approached, many states passed “blue sky laws” to regulate securities sales and protect the public from fraud.

It would take an act of Congress in 1934 to stop skilled business hucksters from taking advantage of unwary investors seeking often fictional profits. Federal lawmakers established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to help rein in exaggerated claims found in newspaper advertisements, mail solicitations, and other stock promotions.

Widely publicized giant oilfield discoveries at Burkburnett, Texas, in 1918 (above) and nearby “Roaring Ranger” one year earlier led to many inexperienced exploration ventures and exaggerated promotions. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Since the U.S. petroleum industry’s earliest booms and busts in Pennsylvania following the Civil War, the need for dependable information and early financial centers — petroleum exchanges — led to a new profession — the oil scout.

As demand for refined kerosene for lamps grew, the search for new oilfields moved to mid-continent. Thousands of exploration and production companies were established. Most drilled dry holes. When wildcat wells (remote) revealed giant oil and natural fields in Texas and Oklahoma, a new generation of business financing hucksters took advantage.

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a massive oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Giant oilfield discoveries in North Texas made headlines, leading to the hundreds of new exploration companies (see Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?). Many began by seeking capital from local investors, often banks, doctors, and civic leaders. Financial swindlers saw opportunities to take advantage of oilfield discoveries and the resulting oil fever.

Newspapers nationwide reported wells with geysers of oil at Electra (1911), Ranger (1917), and the “World’s Wonder Oilfield” of Boom Town Burkburnett (1918). Publicity about these oil booms rekindled enthusiasm for Texas petroleum riches not seen since the giant oilfield discovery at Spindletop Hill in 1901, the famous “Lucas Gusher.”

Sudden, unexpected “black gold” or “Texas tea” wealth brought prosperity to struggling farming communities. Thanks to the Ranger oilfield, Eastland County’s Merriman Baptist Church (and graveyard) was once declared the richest church in America.

Black Gold Dreams

Criminals specializing in financial deception joined the influx of drilling contractors, workers, equipment suppliers, lease brokers, and associated oilfield service companies. In part to combat fraud in North Texas, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), founded in 1917, American Petroleum Institute (API), founded in 1919, and other industry associations organized.

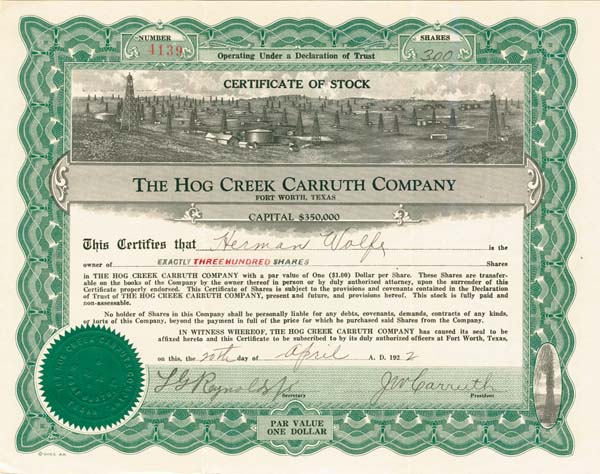

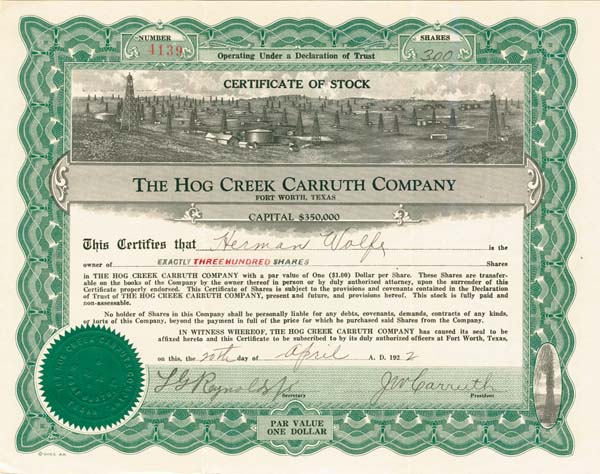

With so many oil boom-inspired companies forming so quickly, the rapid printing of eye-catching but boiler-plate stock certificates often occurred (see Oil Prospects Inc. for one of the most common certificate vignettes).

In a rush to find investors, quickly formed exploration companies ended up using the same oilfield scene for stock certificates. It might have saved time and money by choosing a printer’s common vignette.

Already iconic U.S. boom towns and busts (see the remarkable 1865 rise and fall of Pithole, Pennsylvania) would help launch major companies like Marathon and Texaco, as did the first California oil wells. New petroleum discoveries attracted experienced companies — and many more inexperienced exploration and production ventures that aggressively sought leases, equipment and men, and investors.

However, with little knowledge of the new science of petroleum geology and drilling technologies, few of newly formed companies would find oil. Most did not survive long in the highly competitive oilfields.

Crowding too many wells on leases and a lack of infrastructure for storing and transporting oil harmed the environment. Many companies learned from hard experience, but more went bankrupt without ever finding oil.

Competing exploration companies, lacking petroleum engineers and efficient production technologies, often overproduced geological formations. Unchecked drilling and oversupply in the oil market led prices to collapse as low as 15 cents per 42-gallon oil barrel in the giant East Texas oilfield of the 1930s.

Huckster of Hog Creek

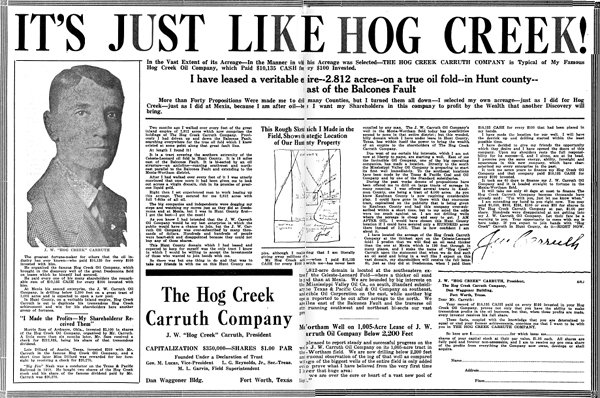

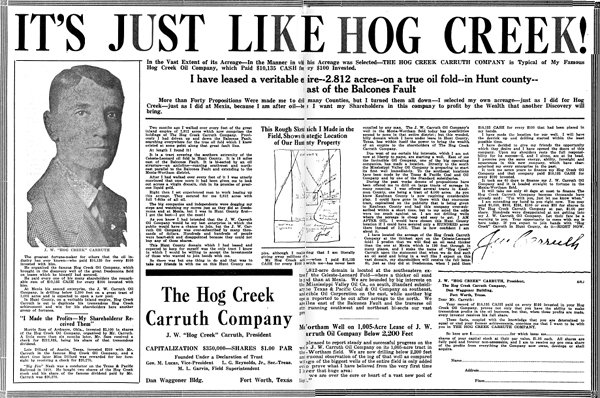

The lure black gold also attracted skilled confidence men who could create oil companies on paper. J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth was among the most notorious.

Financial World in 1912 described “Hog Creek” Carruth as a con man who made a fortune selling worthless oil stocks. The magazine also cited the far better known infamous explorer Dr. Frederick Cook (learn more in Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter).

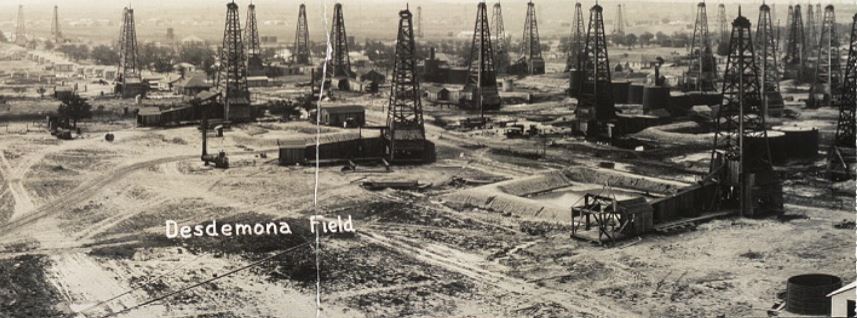

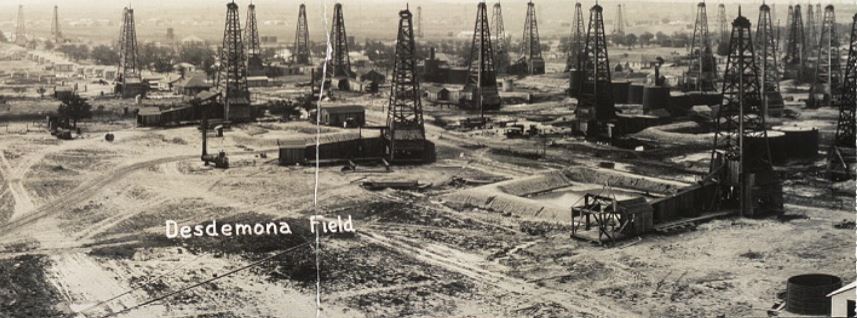

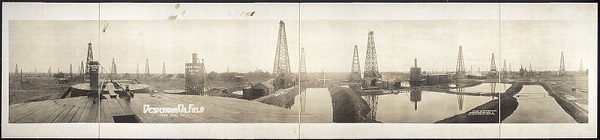

In September 1918 a discovery well near Desdemona blew in after reaching a depth of 2,960 feet, initially producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day. “Unlike Ranger, Desdemona was a small operator’s field. Production reached a peak of 7,375,825 barrels in 1919, and then dropped sharply, chiefly because of over drilling,” according to the Handbook of Texas Online.

“Hog Creek” Carruth proclaimed himself to be the discoverer of the Desdemona oilfield (he was not). He advertised expansively to sell worthless stocks inflated by his phony reputation.

Pilgrim Oil Company

Pilgrim Oil Company formed as a common law trust estate (unincorporated business managed by trustees) in Fort Worth, Texas, on December 20, 1920. The company’s trustees included George M. Richardson and Warren H. Hollister. and was capitalized at $1 million with 100,000 shares offered at par value of $10.

The petroleum company, another fraudulent enterprise of J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth, would be his last.

J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth falsely claimed to have discovered the Desdemona, oilfield, along Hogg Creek. Detail from circa 1919 panoramic photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The oilfield along Hog Creek had been discovered in 1918, just one year after the famous Ranger well. This new field at Desdemona (once called Hog Town) attracted the usual rush of new exploration companies, many with little or no drilling experience.

Among the Eastland County startups, a wily financial conman’s Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company profited by colorful stock sale advertisements to attract investors.

The skillfully exaggerated promotions of Carruth prompted one contemporary writer to admire the crook’s audacity. “Any reader who cannot get a thrill out of Carruth’s highly colored advertising literature is indeed phlegmatic,” the observer declared.

But harm to many small, unwary investors was real. Most of the stock sales’ dollars went into Carruth’s pockets instead of his companies. Even the failure of his oil companies became part of his schemes.

Hogg Oil + Hog Creek Carruth Oil

Carruth merged two of his insolvent petroleum companies — Hogg Oil Company and Hogg Creek Carruth Oil Company — to create the Pilgrim Oil Company. His latest venture attracted some skeptical attention from financial magazine editors. The Pilgrim Oil Company, “makes a business of gathering in defunct oil companies,” reported Financial World.

As part of his connived merger game plan, stockholders of the two bankrupt Carruth oil ventures had to buy an additional 25 percent of Pilgrim Oil Company shares (in cash) or lose their investments entirely. Carruth used this money to pay dividends, thereby luring more buyers into his petroleum company Ponzi scheme.

Financial World noted, “This is a promoter’s way of reloading old stockholders with additional $25 worth of stock for every $100 they hold in a defunct company.”

J.W. Carruth merged his fraudulent Hogg Creek Carruth Oil with his other fraudulent oil company to create Pilgrim Oil company, a Ponzi scheme using investors’ purchase money to pay dividends and lure more buyers.

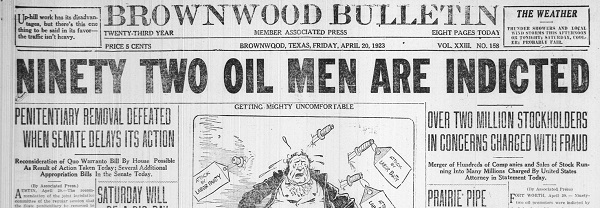

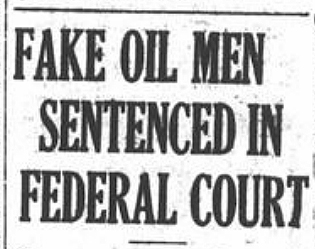

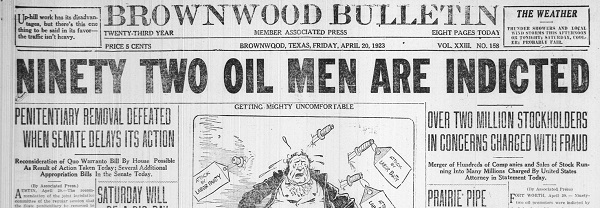

In 1923, a federal court indicted J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth for mail fraud. Also indicted were Pilgrim Oil Company trustees Richardson and Hollister. Eighty-nine other shady characters also were named in a sweeping indictment aimed at stock hucksters.

U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth

Federal prosecutors reviewed financial harm to innocent Pilgrim Oil Company shareholders, who pleaded to the court for justice.

“False, fraudulent, and untrue representations were made for the purpose of inducing plaintiffs to buy the said stock of the said two companies, and for the purpose of cheating, swindling, and defrauding plaintiffs out of their money, and did cheat, swindle, and defraud plaintiffs out of their said money,” the attorneys declared.

“That in 1922, and for a long time prior and subsequent thereto, defendant was engaged in handling and selling oil stock certificates and owned and controlled interests in various oil companies and concerns in this state,” the prosecutors added. Dozens of convictions followed.

Carruth earned a one-year sentence in Leavenworth, Kansas. He joined the federal penitentiary’s oil-scheme alumni Dr. Frederick Cook, the fraudulent Arctic explorer turned oil well promoter. Pilgrim Oil Company and the other Carruth company shareholders were left with stock certificates of no value, except perhaps as a family stories and heirlooms.

Convicted felon “Hog Creek” Carruth, who died in obscurity in 1932, should not be confused with former Texas Governor James S. “Big Jim” Hogg, who helped discover the important West Columbia oilfield in 1917 — learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells.

New Jersey Oilfield?

A West Coast newspaper in 1916 reported on a rare attempt to find an East Coast oilfield. “Lewis Steelman, the man who has been prospecting for oil near Millville, N.J., for some time, has begun active work to locate an oil well and he confidently expects to strike the fluid,” reported California’s Santa Ana Register.

In New Jersey, the recently established Steelman Realty Gas & Oil Company was selling stock buttressed by the declarations of Dr. H. J. von Hagen, who company executives cited as “one of the world’s greatest living geologists and petroleum engineers.” Learn more in Fake New Jersey Oil Well.

More articles about U.S. exploration and production companies and links for further research can be found in Oil Stock Certificates.

_______________________

Recommended Reading (October 9): The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS annual supporter. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pilgrim-oil-company-exploiting-oil-fever. Last Updated: May 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 9, 2021.

.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Speculators once again converged on a small town in Eastland County in 1918 as yet another West Texas drilling boom began with a gusher. Spear Oil Company soon joined them.

In September a well producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day had blown in near Desdemona, one of the first Texas towns established west of the Brazos River.

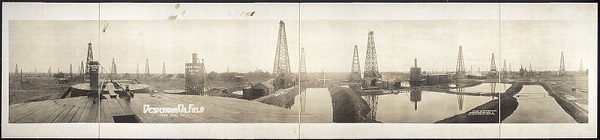

The Desdemona oilfield, Eastland County, Texas, circa 1919. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Desdemona had once been called Hog Town and Hog Creek Oil Company made the discovery (not a skilled conman’s Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company). Eastland County’s Ranger and Cisco communities experienced drilling booms the previous year.

The “Roaring Ranger” McClesky No. 1 well of October 1917 had reached a daily production of 1,700 barrels. Within two years eight refineries were open or under construction and Ranger banks had $5 million in deposits. ALso in North Texas, a 1918 gusher created boom town Burkburnett.

That oil field gained international fame for Ranger as the town that wiped out oil shortages during World War I, allowing the Allies to “float to victory on a wave of oil.” Eastland County’s Cisco would later gain fame as the crowded boom town Conrad Hilton visited after the war — and bought his first motel (see Oil Boom brings First Hilton Hotel).

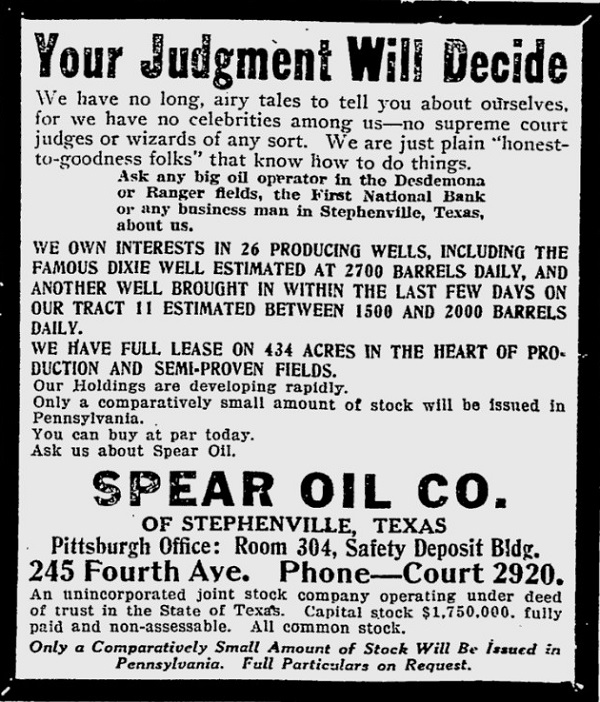

Spear Oil Company

Spear Oil Company organized with capitalization of $1.75 million in 1919 — the same year the Desdemona field reached its peak annual production of almost 7.4 million barrels of oil.

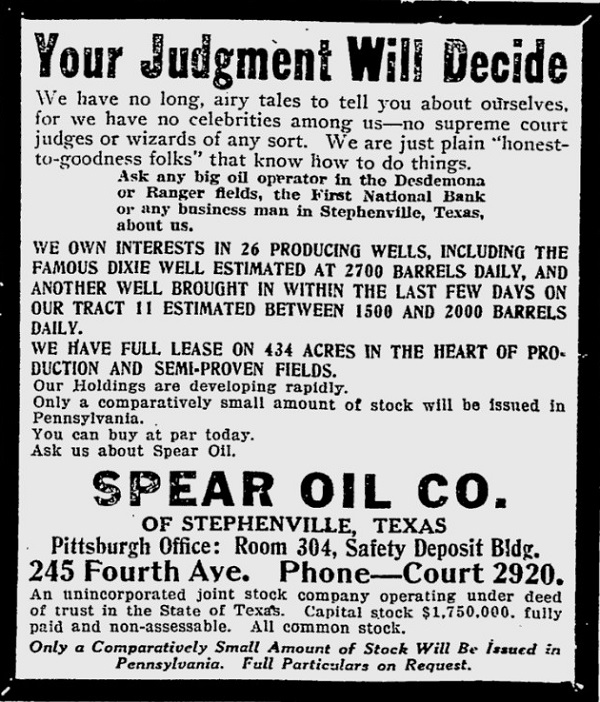

With J.A. Spear as president and leases to drill in Desdemona, widespread promotion of stock sales was necessary to fund the of Stephensville, Texas, based new venture’s operations. But at least one oil stock promoter who had misrepresented the value of the region’s wells in 1914 was serving time in federal prison.

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

These new laws were designed to prevent the use of the U.S. Mail in stock promotion schemes. The South Carolina attorney general’s rejection excoriated the practice of “selling script or certificates of so-called ‘stock’ in the leasing and operation of what is claimed to be prospective development, producing and marketing of oil and gas in Texas.”

The trade publication United States Investor agreed. “We do not recommend Spear Oil as a purchase,” noted the magazine’s editors. “Apparently the people at the head of this company are much more at home selling stock than they are in operating an oil enterprise.”

Nonetheless, within a few months, a Wilmington newspaper published an “editorial” letter (no doubt paid for by the company) extolling Spear Oil Company properties.

Newspaper Ads and Editorials

“There are a number of wells being drilled on their royalties and several locations for wells on their solid leases,” the Wilmington Morning Star reported. “As a whole, we consider the securities of Spear Oil Company safe, with prospects for at least good, substantial dividends for many years and each of us has purchased a number of shares of their securities.”

The letter concluded: “In conclusion, we found the conditions and general outlook for the success of the company much better than we had expected, and even better than it had been represented to us. Respectfully submitted…”

Spear Oil did drill in Eastland County and complete oil wells. United States Investor was obliged to update and report net production of about 600 to 650 barrels per day from the company’s Desdemona operations in the southeast corner of Eastland County.

The company’s stock was still offered on the Fort Worth Exchange at $1.40 a share in September 1920, although it had not paid dividends and, “as yet and appears to be using its earnings for further development.” As far away as North Tonawanda, New York, promoters of Spear Oil wrote enthusiastic endorsements recommending the company’s stock.

Drilling a Well

In 1921, Spear Oil Company spudded its Blankenship No. 1 well, but soon shut it down and moved two strings of tools and three rigs to begin operations on another promising lease. The Blankenship No. 2 well’s progress was noted in oil trade publications.

“The Desdemona field now has approximately 315 completed wells that have a daily average production ranging from 4,000 to 6,000 barrels,” Oil Weekly reported on January 14, 1922.

“During the past week, the Spear Oil Company’s No. 2 Blankenship failed to show up as a producer after being shot with 20 quarts from 3,060 to 3,070 feet,” the publication added. “This well has a total depth of 3,085 feet, and is now being cleaned out.”

Learn more how a well was “shot” in Shooters – A Fracking History.

Meanwhile, the impact of over-drilling was clear as reservoir pressures and production from the field diminished. Spear Oil’s Blankenship No. 2 well failed along with many others and funding for continued operations could not be secured.

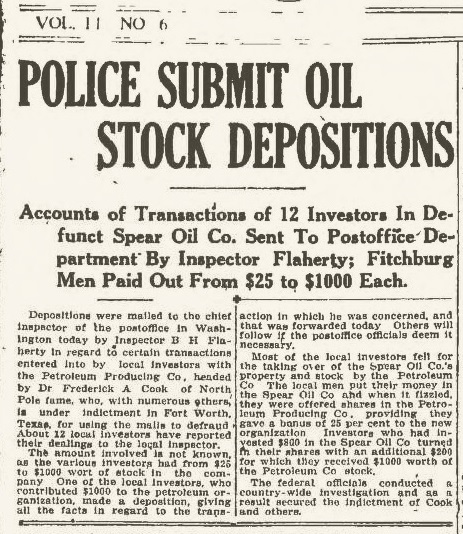

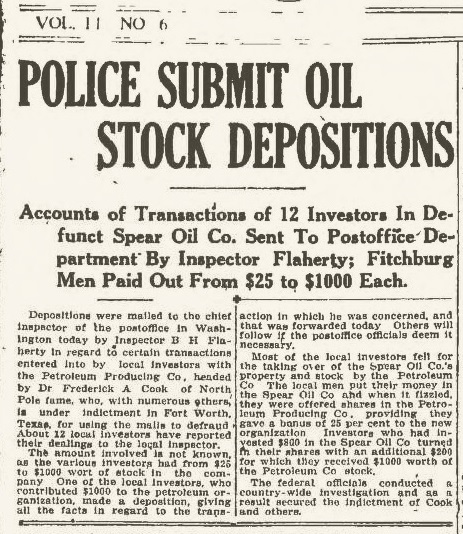

Stockholders of the failing Spear Oil Company were approached in 1923 by the famed (but fraudulent) North Pole explorer, Frederick Cook and his Petroleum Producers’ Association.

Cook’s stock manipulations and violations of blue sky laws ultimately landed him in prison, but not before many Spear Oil share owners were conned into exchanging their stock for Petroleum Producers’ Association while paying a 25 percent “bonus.”

Learn more about Cook in Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

Petroleum Producers’ Association stock was as worthless as Spear Oil Company’s, but investors were convinced otherwise, largely through the extraordinary promotional machinations of Seymour Cox. “Alphabet” Cox. The skilled huckster and others were convicted of ”dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

Another notable fraudster, J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth, created Pilgrim Oil Company and other shady oilfield ventures solely to bilk unwary investors.

It was not until 1934 that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was established to regulate the issue and sale of securities and to protect the public from increasingly clever stock promotions and manipulations. By then, Spear Oil Company was long gone. Its stock certificates may have value to scripophily collectors.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Spear Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: September 7, 2021. Original Published Date: February 1, 2014.

.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 11, 2014 | Petroleum Companies

Exploring the companies and Ponzi schemes of a 1920s fake oilman.

Wherever men meet “to tell stories of great achievements of the gigantic industry, someone will always tell, amid a breathless silence, the amazing story of Hog Creek Carruth.”

He called himself J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth. The investors he betrayed do doubt called him much worse. His “amazing story” began in a Texas boom town.

Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company was one of several Texas exploration companies created by Carruth, who gained his nickname after falsely claiming to have discovered the giant Desdemona oilfield at Hogg Creek.

The Hog Creek Carruth Company was among several 1920s companies formed to take advantage of unwary investors seek petroleum wealth in Eastland County, Texas.

In fact, it was Tom Dees and the Hog Creek Oil Company that brought in Desdemona’s discovery well on September 2, 1918. The historic well blew in at 2,000 barrels of oil a day, delighting company investors, who reportedly profited more than $100 for every dollar they had invested. Carruth was among them.

“Hog Creek” Carruth, Stock Promoter

Located along Hog Creek and once called Hogtown, abundant oil production caused Desdemona to boom — and speculators to swarm. As it revelled in its newfound wealth, the town earned a nasty reputation. Texas Rangers had to intervene to keep order. Carruth’s relentless self-promotion and exuberant claims about the discovery soon earned him the “Hog Creek” Carruth moniker.

“The tiny peanut-farming hamlet of Desdemona in Eastland County was transformed when oil was struck in 1918,” notes the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. “Tents and shacks sprang up all around the town to house speculators and workers who flocked to the area, and the population grew from 340 to 16,000 almost overnight.”

Awash with prosperity, people and mud, by April 1920 the Texas Rangers had to be sent into Desdemona to keep order in the oil boomtown.

A contemporary account of the boom reported, “tales of Hogtown during the wicked oil days are too lurid for these pages, but we can say that its debauchery might be so well remembered because so much of it supposedly took place in broad daylight and sometimes not in private.”

Similar Texas drilling booms were taking place in Burkburnett along the Red River and in nearby Ranger, where the “Roaring Ranger” of October 1917 was Eastland County’s first gusher. Read more in Pump Jack Capital of Texas.

With speculators eager to profit from Desdemona, Carruth formed the J. W. Carruth Oil Company in 1919. Despite drilling several dry holes, he profited from selling his exuberantly advertised company stock.

However, just one year after its discovery, the Desdemona oilfield’s production would reach its peak of 7,375,825 barrels and then drop sharply, chiefly because of over drilling, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

Profiting from “Sucker Lists”

J.W. Carruth and his oil company prospered in 1919 by becoming a Ponzi scheme in which Carruth used naïve investors’ purchase money to pay dividends, thereby luring more buyers in a spiral which lined his pockets while emptying theirs. He personally profited by selling his buyers’ personal information.

“Sucker lists” with names, addresses and investment history of people who might buy oil shares had great value. The lists expanded during the multiple oil booms in Eastland County – and similar discoveries in Oklahoma, Kansas and California.

“Depending on the extent and quality of a list, its price ran from several hundred dollars to several thousand,” notes Roger Olien in his 1990 book, Easy Money: Oil Promoters And Investors In The Jazz Age. Predictably for Carruth Oil Company, litigation dogged “Hog Creek” Carruth.

Disputes over leasing and mineral rights continued for several years. He nonetheless sold about $600,000 worth of stock. After more dry holes and more stock sales, in January of 1922, Carruth even announced a new venture.

“I have called this company the Hog Creek Carruth Company, since it resembled so closely the famous Hog Creek Oil Company which I organized in 1917 and which in 1918 paid $10,135 cash dividends for every $100 that had been invested in it,” Carruth proclaimed.

Producing a blizzard of full-page promotions in newspapers from Ft. Worth to San Antonio and Port Arthur, the oil stock salesman finally ran afoul of “blue sky” laws, which sought to restrain such scams.

“The advertising of still another promoter, ‘Hog Creek’ Carruth of Fort Worth, Texas, caps the climax,” reported the Providence News on January 3, 1923.

“Modestly he admits that wherever men meet to ‘tell stories of great achievements of the gigantic industry, someone will always tell, amid a breathless silence, the amazing story of Hog Creek Carruth.’”

Indicted in 1923 along with 25 other Texas promoters for “fraudulent use of U.S. mails,” Carruth joined some nationally recognized swindlers.

Among those indicted were some of the most infamous stock promoters of the day: Dr. Frederick Cook, who had falsely claimed to have discovered the North Pole before Robert Perry, and the “genius of bunkum,” Seymour E. J. “Alphabet” Cox, the author of such enticements as, “Oil! Guaranteed Gushers! Five hundred percent, dividends. Pots of gold!”

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

“Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.

“Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.

In 1934 the Securities and Exchange Commission was established to regulate the issue and sale of securities to protect the public from deceptive stock promotions. Also see the Spear Oil Company and Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth’s fraudulent oil ventures (also see Pilgrim Oil Company) have left behind stock certificates as family heirlooms that might some value for some financial certificate collectors. The history of more legitimate exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: September 9, 2021. Original Published Date: March 11, 2018.

.

(2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

After testimony from almost 300 witnesses and a lengthy trial, Carruth, Cook, Cox and others were convicted of “dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.” “Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.

“Hog Creek” Carruth was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for a year. He died in obscurity in 1932.