by Bruce Wells | Jun 26, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover in the 1920s launched the Arkansas petroleum industry.

Arkansas oil wells of the 1920s created boom towns, established the state’s petroleum exploration and production industry, and boosted the career of a young wildcatter named Haroldson Lafayette Hunt.

The first Arkansas well that yielded “sufficient quantities of oil” was the Hunter No. 1 of April 16, 1920, in Ouachita County, according to the Arkansas Geological Survey. Natural gas was discovered a few days later in Union County by Constantine Oil and Refining Company.

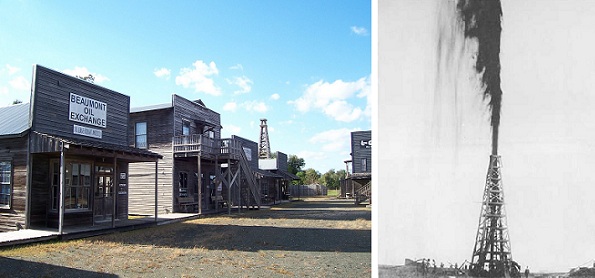

Surrounded by 20 acres of woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in the Smackover oilfield preserves the state’s petroleum history seven miles north of equally historic El Dorado.

A January 1921 well drilled in the same Union County field at El Dorado marked the true beginning of commercial oil production in Arkansas. When the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well struck oil in 1921, the oilfield discovery soon catapulted the population of El Dorado from 4,000 to 25,000 people. The well, 15 miles north of the Louisiana border, was the state’s first commercial oil well.

“Twenty-two trains a day were soon running in and out of El Dorado,” noted the Arkansas Gazette. An excited state legislature announced plans for a special railway excursion for lawmakers to visit the oil well in Union County.

Meanwhile, Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt arrived from Texas with $50. He joined the crowd of lease traders and speculators at the Garrett Hotel, where fortunes were being made — and lost. Hunt launched his start as an independent oil and natural gas producer during the El Dorado drilling boom.

Some locals said it was his expertise at the poker table that earned him enough to afford a one-half acre parcel lease where his Hunt-Pickering No. 1 well produced some oil, but ultimately proved unprofitable.

Hunt persevered, and within four years acquired substantial El Dorado and Smackover oilfield holdings. By 1925, he was a successful 36-year-old oilman with his wife Lyda and three young children living in a three-story El Dorado home. He would significantly add to his oilfield successes a decade later in Kilgore, Texas (learn more in East Texas Oilfield Discovery).

Giant Oilfield at El Dorado

Located on a hill a little over a mile southwest of El Dorado, the derrick was visible from the town, according to historians A.R. and R.B. Buckalew. They write that three “gassers” had been completed in the general vicinity, but did not produce in commercial quantities.

There was no market for natural gas at the time, the authors explained in their 1974 book, The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924.

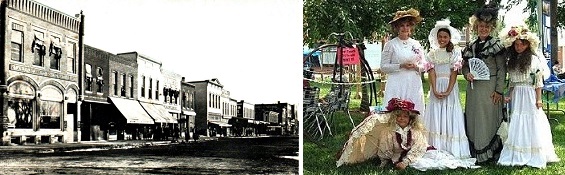

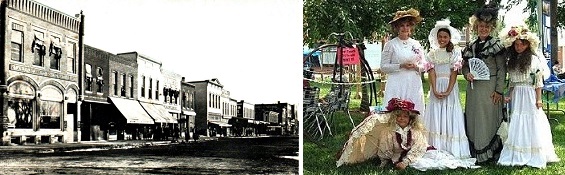

The Garrett Hotel, where H.L. Hunt checked in with 50 borrowed dollars and launched his long career as a successful independent oil producer.

Yet Dr. Samuel T. Busey was convinced “there was oil down there somewhere.”

The authors added, “Among those who gambled their savings with Busey at this time were Wong Hing, also called Charles Louis, a Chinese laundry man, and Ike Felsenthal, whose family had created a community in southeast Union County in earlier years.”

With no oil production nearby, investing in the “wildcat” well was a leap of faith. Chal Daniels, who was overseeing drilling operations for Busey, contributed the hefty sum of $1,000. On January 10, 1921, the well had been drilled to 2,233 feet and reached the Nacatoch Sand. A small crowd of onlookers and the drilling crew — after moving a safe distance away — watched and listened.

“The spectators, among them Dr. Busey, watched with an air of expectancy,” noted the historians. “Drilling had ceased and bailing operations had begun to try to bring in the well. At about 4:30 p.m., as the bailer was being lifted from its sixth trip into the deep hole, a rumble from deep in the well was heard.”

The rumbling grew in intensity, “shaking the derrick and the very ground on which it stood as if an earthquake were passing,” the authors report. “Suddenly, with a deafening roar, ‘a thick black column’ of gas and oil and water shot out of the well,” they added.

The gusher blew through the derrick and “bursts into a black mushroom” cloud against the January sky. The Busey No. 1 well produced 15,000,000 to 35,000,000 cubic feet of gas and from 3,000 to 10,000 barrels of oil and water a day.

Petroleum brings Prosperity

Thanks to the El Dorado discovery, the first Arkansas petroleum boom was on. By 1922, there were 900 producing wells in the state.

Civic leaders raised funds to preserve El Dorado’s historic downtown – and add an Oil Heritage Park at 101 East Main Street.

“Three months after the Busey well came in, work was underway on an amusement park located three blocks from the town that would include a swimming pool, picnic grounds, rides and concessions,” noted the Union County Sheriff’s Office. “Culture was not forgotten as an old cotton shed in the center of town near the railroad tracks was converted to an auditorium.”

The 68-square-mile field will lead U.S. oil output in 1925 – with production reaching 70 million barrels. “It was a scene never again to be equaled in El Dorado’s history, nor would the town and its people ever be the same again,” the authors concluded. “Union County’s dream of oil had come true.”

In 2002, El Dorado gathered 40 local artists to paint 55 oil drums donated by the local Murphy Oil Company. Preserving the town’s historic assets, including boom-era buildings, remains a major goal of the local group, Main Street El Dorado, which was the “2009 Great American Main Street Award Winner” of the National Trust Main Street Center.

Second Oil Boom: Discovery at Smackover

Prior to the January 1921 El Dorado discovery, the region’s economy relied almost exclusively on the cotton and timber industries “that thrived in the vast virgin forests of southern Arkansas.”

Petroleum wealth helped Smackover, Arkansas, incorporate in 1922.

Six months after the Busey-Armgstrong No. 1, another giant oilfield discovery 12 miles north will bring national attention – and lead to the incorporation of Smackover. A small agricultural and sawmill community with a population of 131, Smackover had been settled by French fur trappers in 1844. They called the area “Sumac-Couvert,” meaning covered with sumac or shumate bushes.

According to historian Don Lambert, by 1908 Sidney Umsted operated a large sawmill and logging venture two miles north of town. He believed that oil lay beneath the surface. “On July 1, 1922, Umsted’s wildcat well (Richardson No. 1) produced a gusher from a depth of 2,066 feet,” Lambert reported.

“Within six months, 1,000 wells had been drilled, with a success rate of ninety-two percent. The little town had increased from a mere ninety to 25,000 and its uncommon name would quickly attain national attention,” added Lambert.

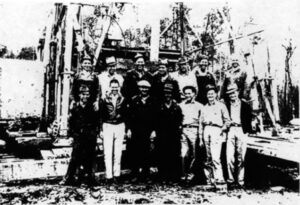

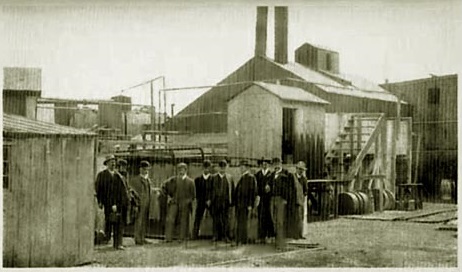

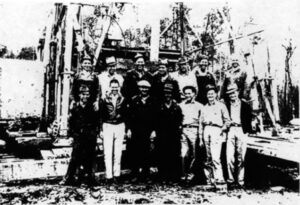

Roughnecks photographed following the July 1, 1922, discovery of the Smackover (Richardson) field in Union County. Courtesy of the Southwest Arkansas Regional Archives.

The oil-producing area of the Smackover field covered more than 25,000 acres. By 1925, it had become the largest-producing oil site in the world. The field will produce 583 million barrels of oil by 2001.

Opened in 1986, the Arkansas Natural Resources Museum educates visitors in the heart of the historic Smackover oilfield. Exhibits explain how the Busey No. 1 well near El Dorado “blew in with a gusty fury” in January 1921.

The museum includes a five-acre Oilfield Park with operating examples of early and modern oil-producing technologies. They can be found one mile south of the once petroleum-rich town of Smackover, which has celebrated its petroleum heritage with an “Oil Town Festival” every June.

Abundant natural gas in the Fayetteville shale formation brought more drilling to Arkansas.

With more than 46,800 wells drilled between 1925 and 2023, about one-third of the 75 Arkansas counties have produced oil and or natural gas, reported Mineralsanswers.com in July 2024.

Southern Arkansas also is considered among the most prolific lithium resources of its type in North America, according to ExxonMobil, which in 2023 acquired the rights to 120,000 gross acres of the Smackover formation.

Fayetteville Shale

Thanks to advances in drilling technologies combined with hydraulic fracturing, the Fayetteville Shale — a 50-mile-wide formation across central Arkansas — has added vast natural gas reserves while creating a new petroleum boom for the state.

Unlike traditional fields containing hydrocarbons in porous formations, shale holds natural gas in a fine-grained rock or “tight sands.” Until the 1990s, drilling in most shale formations was not considered profitable for production.

Surrounded by 20 acres of lush woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources collects and exhibits southern Arkansas petroleum – along with the history of brine drilling and the salt industry. It also has documented the social and economic histories that accompanied the 1920s oil boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924 (1974); The Three Families of H. L. Hunt (1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Arkansas Oil Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/arkansas-oil-and-gas-boom-towns. Last Updated: January 3, 2025. Original Published Date: April 21, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 24, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

March 24, 1989 – Exxon Valdez hits Bligh Reef –

After almost 12 years of routine passages by oil tankers through Prince William Sound, Alaska, supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef, resulting in an oil spill affecting 1,300 miles of shoreline. Vessels carrying North Slope oil had safely passed through the sound more than 8,700 times.

Eight of Exxon Valdez’s 11 tanks were punctured and an estimated 260,000 barrels of oil spilled, affecting hundreds of miles of coastline. Investigators later found that an error in navigation by the third mate, possibly due to fatigue or excessive workload, had caused the accident.

Shown being towed away from Bligh Reef, the Exxon Valdez had been outside shipping lanes when it ran aground in March 1989. Photo courtesy Erik Hill, Anchorage Daily News.

When the 987-foot tanker hit the reef that night, “the system designed to carry two million barrels of North Slope oil to West Coast and Gulf Coast markets daily had worked perhaps too well,” noted the Alaska Oil Spill Commission. “At least partly because of the success of the Valdez tanker trade, a general complacency had come to permeate the operation and oversight of the entire system.”

Learn more in Exxon Valdez Oil Spill.

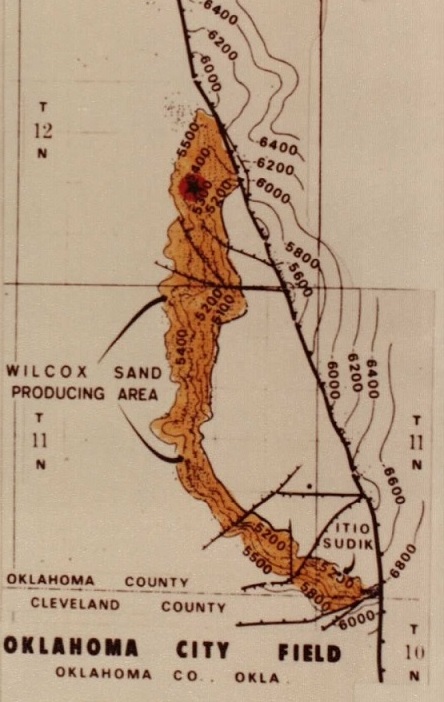

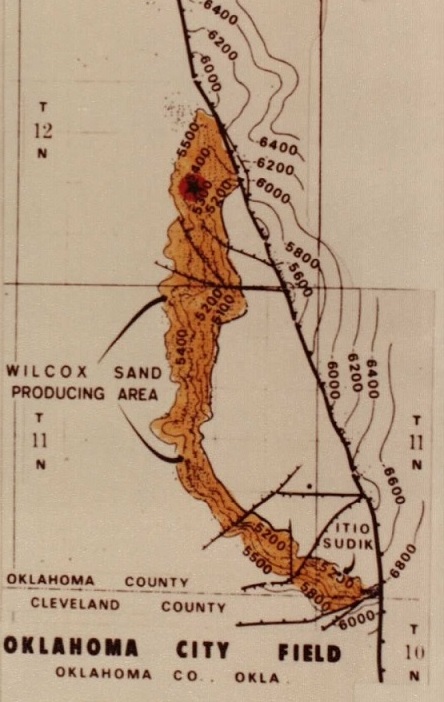

March 26, 1930 – “Wild Mary Sudik” makes Headlines

What would become one of Oklahoma’s most famous wells struck a high-pressure formation about 6,500 feet beneath Oklahoma City and oil erupted skyward. The Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company’s Mary Sudik No. 1 flowed for 11 days before being brought under control. It produced about 20,000 barrels of oil and 200 million cubic feet of natural gas daily, becoming a worldwide sensation.

Highly pressured natural gas from the Wilcox formation proved difficult to control in the prolific Oklahoma City oilfield. Within a week of a 1930 gusher, Hollywood newsreels of it appeared in theaters across America. Photo courtesy Oklahoma History Center.

Efforts to control the well in Oklahoma City’s prolific oilfield (discovered in 1928) were featured on movie newsreels and national radio broadcasts. It was later learned that after drilling more than a mile deep, the exhausted crew did not realize the Wilcox Sand oil formation was permeated with highly pressurized natural gas.

Map of the Wilcox sands formation of the Oklahoma City oilfield in the 1940s.

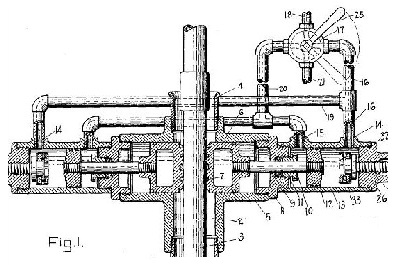

Although the first ram-type blowout preventer (BOP) had been patented in 1926, deep oil and natural gas fields would take time to tame.

Learn more in “Wild Mary Sudik.”

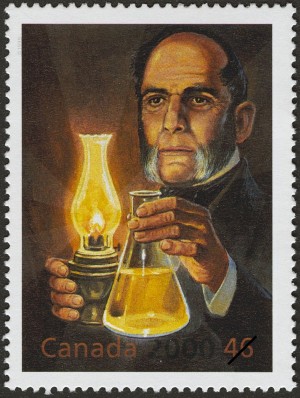

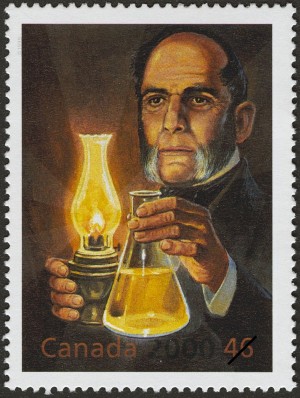

March 27, 1855 – Canadian Chemist trademarks Kerosene

Canadian physician and chemist Abraham Gesner (1797-1864) patented a process to distill coal into kerosene. “I have invented and discovered a new and useful manufacture or composition of matter, being a new liquid hydrocarbon, which I denominate Kerosene,” he proclaimed. Because his new illuminating fluid was extracted from coal, consumers called it “coal oil” as often as kerosene.

On March 17, 2000, Canada issued one million commemorative stamps featuring kerosene inventor Abraham Gesner.

Gesner, considered the father of the Canadian petroleum industry, in 1842 established Canada’s first natural history museum, the New Brunswick Museum, which today houses one of Canada’s oldest geological collections. America’s petroleum industry began when it was learned oil could be distilled into a lamp fuel.

Learn more in Camphene to Kerosene Lamps.

March 27, 1975 – First Pipe laid for Trans-Alaskan Pipeline

With the laying of the first section of pipe in Alaska, construction began on the largest private construction project in American history at the time. Recognized as a landmark of engineering, the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline system, including pumping stations and the Valdez Marine Terminal, would cost $8 billion by the time it was completed in 1977.

Learn more in Trans-Alaska Pipeline History.

March 27, 1999 – Offshore Platform Rocket Launch Test

The Ocean Odyssey, a converted semi-submersible drilling platform, launched a Russian rocket that placed a demonstration satellite into geostationary orbit.

The Zenit-3SL rocket, fueled by liquid oxygen and kerosene rocket fuel, was part of Sea Launch, a Boeing-led consortium of companies from the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and Norway. The platform had once been used by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) for North Sea exploration.

With an orbital test on March 27, 1999, the Ocean Odyssey, a converted semi-submersible drilling platform, became the world’s first floating equatorial launch pad. Photo courtesy Sea Launch.

“The Sea Launch rocket successfully completed its maiden flight today,” Boeing announced. “The event, which placed a demonstration payload into geostationary transfer orbit, marked the first commercial launch from a floating platform at sea.”

The Sea Launch consortium provided orbital launch services until 2014, when Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula of Ukraine.

Learn more in Offshore Rocket Launcher.

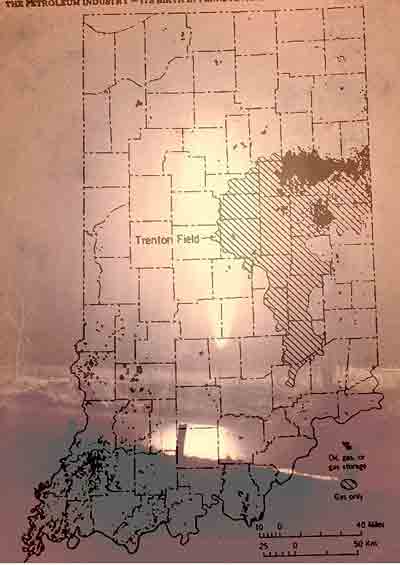

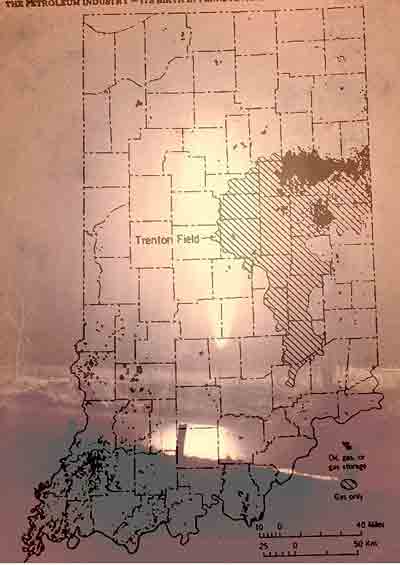

March 28, 1886 – Natural Gas Boom begins in Indiana

Petroleum exploration companies converged on Portland, Indiana, after the Eureka Gas and Oil Company discovered a natural gas field after drilling just 700 feet deep. The well began producing two months after a spectacular natural gas well about 100 miles to the northeast — the “Great Karg Well” of Findlay, Ohio.

According to industrialist Andrew Carnegie, natural gas daily replaced 10,000 tons of coal for making steel.

Portland foundry owner Henry Sees had followed the news from Findlay. He persuaded local investors to drill for Indiana natural gas. In western Pennsylvania, reserves found near Pittsburg had encouraged industrialists there to replace their coal-fired steel and glass foundries with the first large-scale industrial use of natural gas.

Indiana would become the world’s largest natural gas producer, thanks to its Trenton limestone stretching more than 5,100 square miles across 17 counties. Within three years, more than 200 companies were drilling, distributing, and selling natural gas.

Learn more in Indiana Natural Gas Boom.

March 28, 1905 – Oil Discovered in North Louisiana

A small oil discovery in Caddo Parish launched a drilling boom in northern Louisiana and brought economic prosperity to Oil City. The Offenhauser No. 1 well was completed at a depth of 1,556 feet, but yielded just five barrels of oil a day and was abandoned. Far more productive wells quickly followed as the Caddo-Pine Island oilfield 20 miles northwest of Shreveport expanded into 80,000 acres.

The Shreveport Chamber of Commerce in 1955 dedicated a 40-foot monument commemorating the 50th anniversary of oil in Caddo Parish. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“This part of Louisiana, of course, was built on the oil and gas industry, and those visitors interested in the technical aspects of oilfield work will find the museum particularly appealing,” notes the Louisiana State Oil and Gas Museum (formerly the Caddo-Pine Island Oil and Historical Museum). More oilfield history can be found in Shreveport, where natural gas was discovered in 1870 — thanks to an ice plant’s water well. To discourage natural gas flaring, Louisiana passed its first conservation law in 1906.

Learn more in Louisiana Oil City Museum.

March 29, 1819 – Birthday of Father of the Petroleum Industry

Edwin Laurentine Drake (1819-1880) was born in Greenville, New York. Forty years later, he used a steam-powered cable-tool rig to drill the first commercial U.S. oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. The former railroad conductor overcame many financial and technical obstacles to make “Drake’s Folly” a milestone in U.S. petroleum history.

Edwin L. Drake (1819-1880) invented a method of driving a pipe down to protect the integrity of the first U.S. oil well. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

Drake pioneered using iron casing to isolate his well from nearby Oil Creek. “In order to overcome the hurdles before him, he invented a ‘drive pipe’ or ‘conductor,’ an invention he unfortunately did not patent,” noted historian Urja Davé in 2008. “Mr. Drake conceived the idea of driving a pipe down to the rock through which to start the drill.”

Determined to find oil for refining into kerosene, Drake drilled near natural seeps and found oil on August 27, 1859, at a depth of 69.5 feet at a site today on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum.

Learn more in Edwin Drake and his Oil Well.

March 29, 1938 – Magnolia Oilfield found in Arkansas

“Kerlyn Wildcat Strike In Southern Arkansas is Sensation of the Oil Country,” proclaimed the local newspaper when a well drilled by Kerlyn Oil Company revealed the 100-million-barrel Magnolia oilfield, adding to the 1920s giant oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover.

Drilling on the Barnett No. 1 well had been suspended because of a lack of money, but geologist and company Vice President Dean McGee urged drilling deeper. He was rewarded with a giant oilfield discovery at the depth of 7,650 feet. McGee later would become an industry pioneer in offshore exploration.

Visit the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in Smackover.

March 30, 1980 – Deadly North Sea Gale

Massive waves during a North Sea gale capsized a floating apartment for Phillips Petroleum Company workers, killing 123 people. The Alexander Kielland platform, 235 miles east of Dundee, Scotland, housed 208 men who worked on a nearby rig in the Ekofisk field. Most of the Phillips workers were from Norway. The platform, converted from a semi-submersible drilling rig, served as overflow accommodation for the Phillips production platform 300 yards away.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, Perspectives on Modern World History (2011); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(2011); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry (1980); Oil Lamps The Kerosene Era In North America

(1980); Oil Lamps The Kerosene Era In North America (1978); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier

(1978); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier (1997); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(1997); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2009); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History (2013); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2013); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 3, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

March 3, 1879 – United States Geological Survey established –

President Rutherford B. Hayes signed legislation creating the United States Geological Survey (USGS) within the Department of the Interior. The legislation resulted from a report by the National Academy of Sciences, which had been asked by Congress to provide a plan for surveying the country.

Original logo for the U.S. Geological Survey and the current one. The motto “science for a changing world” was added in 1997.

The new agency’s mission included “classification of the public lands, and examination of the geological structure, mineral resources, and products of the national domain,” according to USGS, which since 1974 has been headquartered on a 105-acre site in Reston, Virginia. USGS maintains the world’s largest library collection dedicated to earth and natural sciences, including more than one million books, 600,000 maps, and 500,000 photographs.

March 3, 1886 – Natural Gas brings light to Paola, Kansas

Paola became the first town in Kansas to use natural gas commercially for illumination. To promote its natural gas resources and attract businesses from nearby Kansas City, civic leaders erected four flambeaux arches in the town square. Pipes were laid for other illuminated displays.

“Pearl Street Looking South, Paola, Kansas” is among images preserved by the Miami County Kansas Historical Society & Museum. An annual Paola Roots Festival began in 1990.

“Paola was lighted with Gas,” proclaimed an exhibit at the Miami County Historical Museum. “The pipeline was completed from the Westfall farm to the square and a grand illumination was held.” By the end of 1887, several Kansas flour mills were fueled by natural gas. Paola’s gas wells would run dry, but more mid-continent oil discoveries would follow

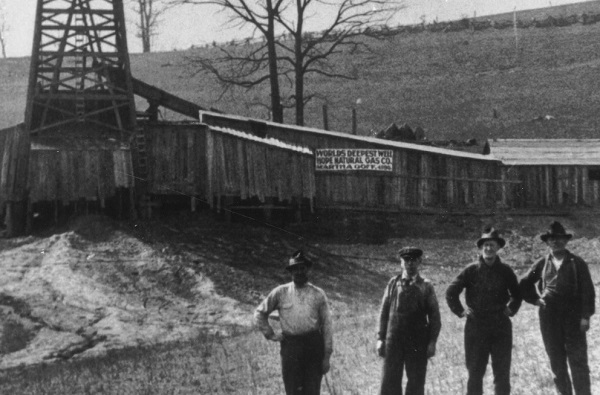

March 4, 1918 – West Virginia Well sets World Depth Record

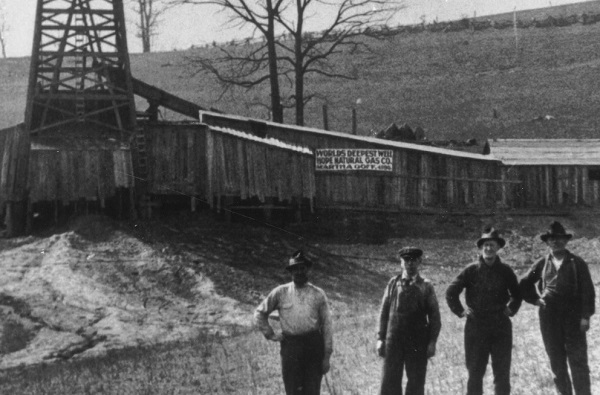

Hope Natural Gas Company completed an oil well at a depth of 7,386 feet on the Martha Goff farm in Harrison County, West Virginia. The cable-tool well became the world’s deepest until surpassed by a 1919 well in nearby Marion County. The previous world record had been a well in Germany at 7,345 feet.

Drilled with cable-tools near Clarksburg, this 1918 West Virginia well was the world’s deepest until one drilled in a neighboring county. Photo courtesy West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association.

In 1953, the New York State Natural Gas Corporation claimed the world’s deepest cable-tool well at a depth of 11,145 feet at Van Etten, New York. A rotary rig depth record was set in 1974 by the Bertha Rogers No. 1 well at 31,441 feet, and a Soviet Union experimental well in 1989 reached 40,230 feet — the current world record.

March 4, 1933 – Oklahoma City Oilfield under Martial Law

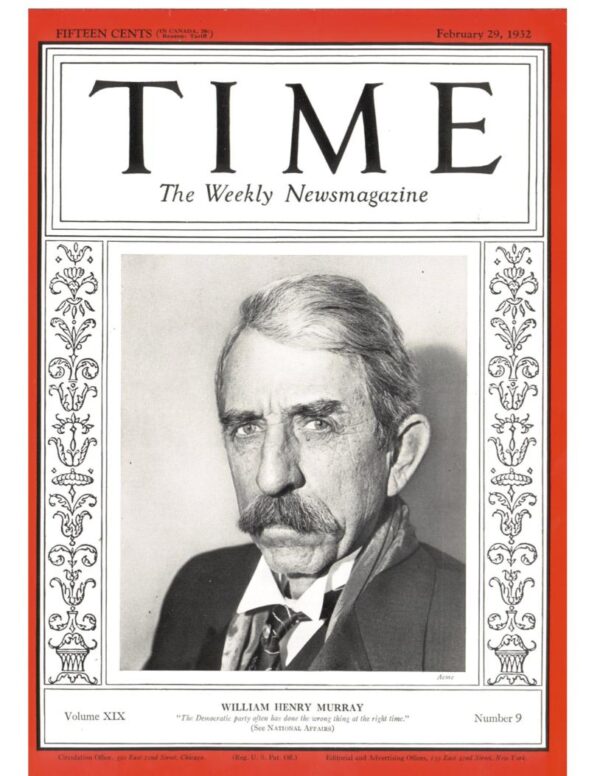

Oklahoma Governor William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray declared martial law to enforce his regulations strictly limiting production in the Oklahoma City oilfield, discovered in December 1928. Two years earlier, Murray had called a meeting of fellow governors from Texas, Kansas and New Mexico to create an Oil States Advisory Committee, “to study the present distressed condition of the petroleum industry.”

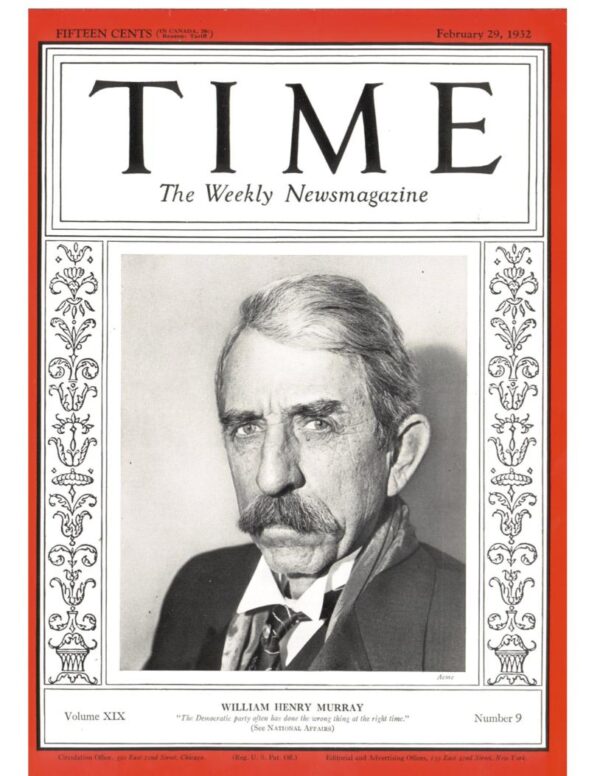

William “Alfalfa Bill” Murray in 1932.

Elected in 1930, the controversial politician was called “Alfalfa Bill” because of speeches urging farmers to plant alfalfa to restore nitrogen to the soil. By the end of his administration, Murray had called out the National Guard 47 times and declared martial law more than 30 times. He was succeeded as Oklahoma governor by E.W. Marland in 1935.

March 4, 1938 – Giant Oilfield discovery in Arkansas

The Kerr-Lynn Oil Company (a Kerr-McGee predecessor) completed its Barnett No. 1 well east of Magnolia, Arkansas, discovering the giant Magnolia oilfield, which would become the largest producing field (in volume) during the early years of World War II, helping to fuel the American war effort.

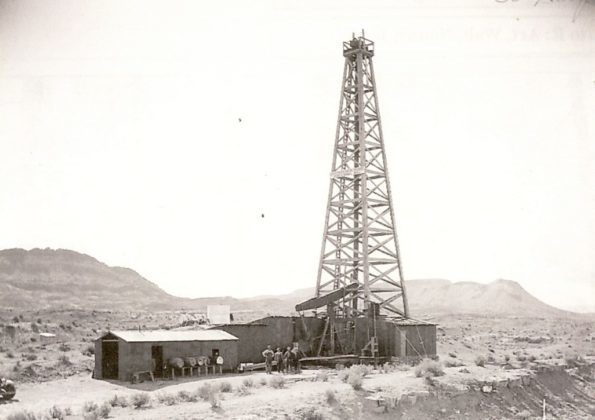

Crew members stand in front of their 1938 giant oilfield discovery well at Magnolia, Arkansas. Photo courtesy W.B. “Buzz” Sawyer.

The southern Arkansas gusher launched a Columbia County oil boom similar to Union County’s Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well southwest of El Dorado in January 1921 (see First Arkansas Oil Wells).

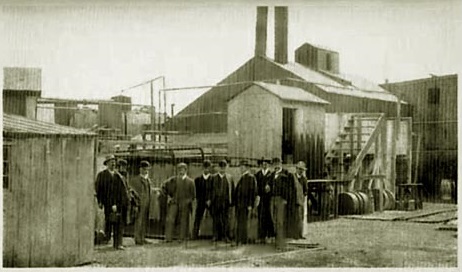

March 5, 1895 – First Wyoming Refinery produces Lubricants

Near the Chicago & North Western railroad tracks in Casper, Civil War veteran Philip “Mark” Shannon and his Pennsylvania investors opened Wyoming’s first refinery. It could produce 100 barrels a day of 15 different grades of lubricant, from “light cylinder oil” to heavy grease. Shannon and his associates incorporated as Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Company.

The original Casper oil refinery in Wyoming, circa 1895. Photo courtesy Wyoming Tales and Trails.

By 1904, Shannon’s company owned 14 wells in the Salt Creek field, about 45 miles from the company’s refinery (two days by wagon). Each well produced up to 40 barrels of oil per day, but transportation costs meant Wyoming oil could not compete for eastern markets. The state’s first petroleum boom began in 1908 with Salt Creek’s “Big Dutch” well.

Learn more in First Wyoming Oil Wells.

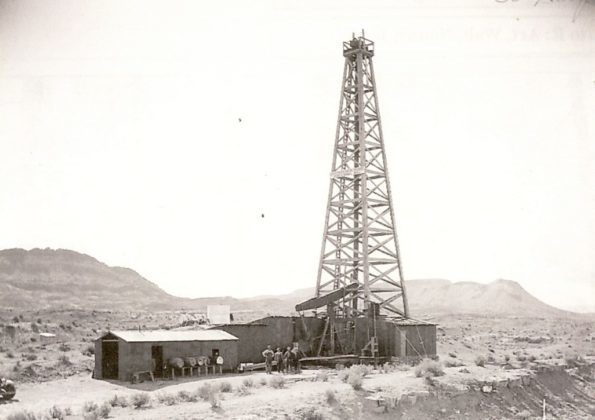

March 6, 1935 – Search for First Utah Oil proves Deadly

More than a decade before Utah’s first commercial oil wells, residents of St. George had hoped the “shooting” of a well drilled by Arrowhead Petroleum Company would bring black gold prosperity. A crowd had gathered to watch as workers prepared six, 10-foot-long explosive canisters to fracture the 3,200-foot-deep Escalante No. 1 well.

The Escalante well heralded new prosperity for residents of nearby St. George, Utah, in 1935 — until an attempt to shoot the well went wrong and canisters of TNT and nitroglycerin exploded. Photo courtesy Washington County Historical Society.

An explosion occurred as the torpedoes, “each loaded with nitroglycerin and TNT and hanging from the derrick,” were being lowered into the well. Ten people died from the detonations, which “sent a shaft of fire into the night that was seen as far as 18 miles away.”

The 1935 accident has remained the worst oil-related disaster in Utah, according to The Escalante Well Incident, a 2007 historical account.

March 6, 1981 — Shale Revolution begins in North Texas

Mitchell Energy and Development Corporation drilled its C.W. Slay No. 1 well, the first commercial natural gas well of the Barnett shale formation. Over the next four years, the vertical well in North Texas produced nearly a billion cubic feet of gas, but it would take almost two decades to perfect cost-effective shale fracturing methods combined with horizontal drilling.

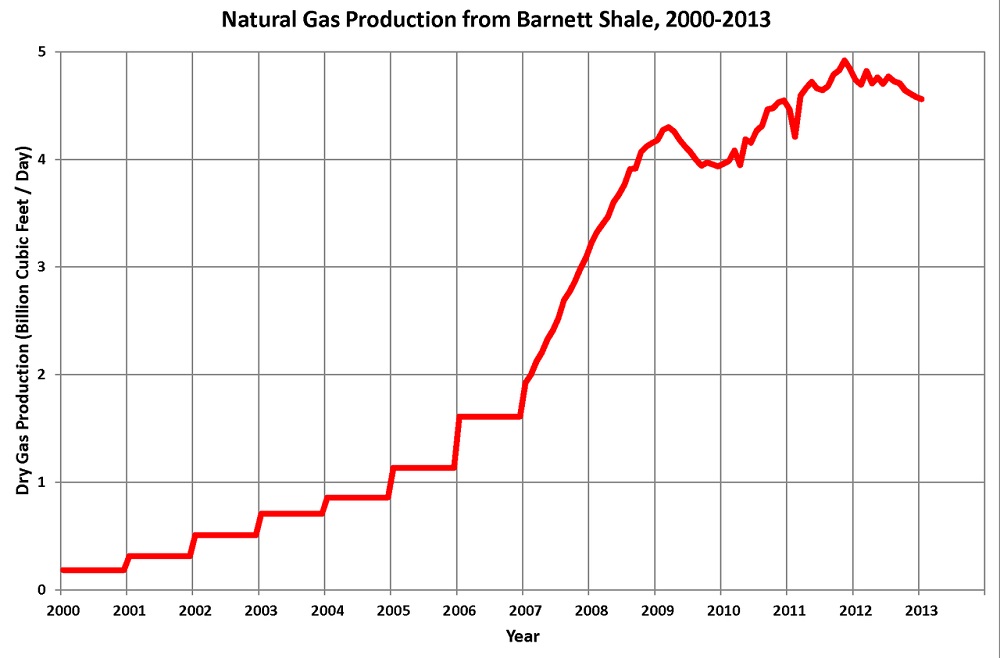

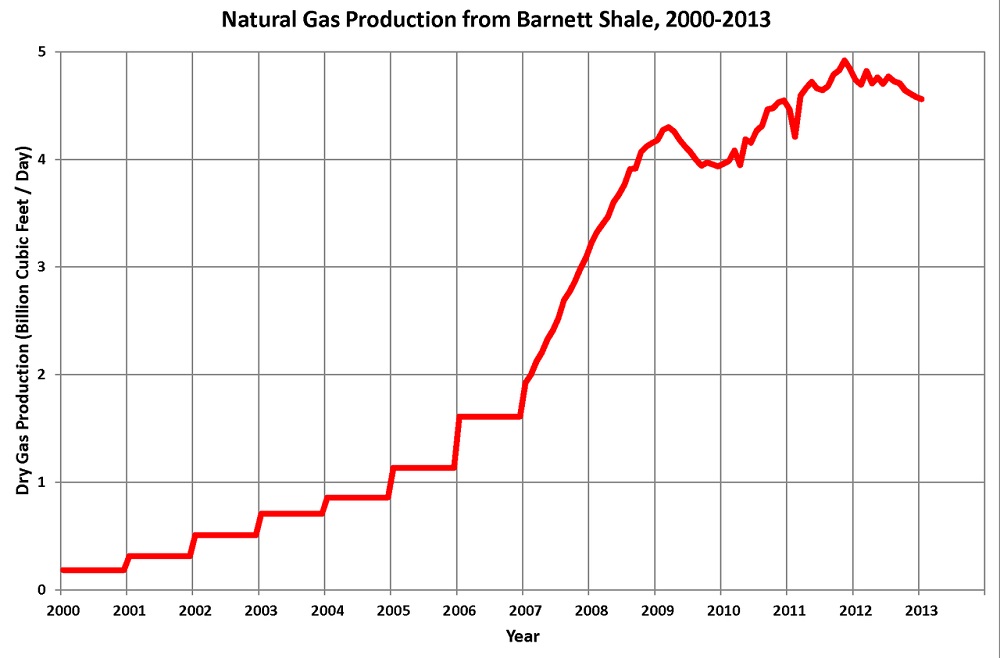

Production from the Barnett shale formation extends from Dallas west and south, covering 5,000 square miles, according to the Texas Railroad Commission. Chart courtesy Dan Plazak.

Mitchell Energy’s 7,500-foot-deep well and others in Wise County helped evaluate seismic and fracturing data to understand deep shale structures. “The C.W. Slay No. 1 and the subsequent wells drilled into the Barnett formation laid the foundation for the shale revolution, proving that natural gas could be extracted from the dense, black rock thousands of feet underground,” the Dallas Morning News later declared.

By the end of 2012, with almost 14,000 wells drilled in the largest gas field in Texas, production started to decline, but the Barnett field still accounted for 6.1 percent of Texas natural gas production and 1.8 percent of the U.S. supply, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

March 7, 1902 – Oil discovered at Sour Lake, Texas

Adding to the giant oilfields of Texas, the Sour Lake field was discovered about 20 miles west of the world-famous Spindletop gusher of January 1901. The spa town of Sour Lake quickly became a boom town where major oil companies, including Texaco, got their start.

“The resort town of Sour Lake, 20 miles northwest of Beaumont, was transformed into an oil boom town when a gusher was hit in 1902,” notes the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Originally settled in 1835 and called Sour Lake Springs because of its “sulphureus spring water” known for healing, the sulfur wells attracted many exploration companies. Some petroleum geologists predicted a Sour Lake salt dome formation similar to that revealed by Pattillo Higgins, the Prophet of Spindletop.

Sour Lake’s 1902 discovery well was the second attempt of the Great Western Company. The well, drilled “north of the old hotel building,” penetrated 40 feet of oil sands before reaching a total depth of about 700 feet. The Hardin County’s salt dome oilfield yielded almost nine million barrels of oil by 1903, when the Texas Company made its first major oil find at Sour Lake.

Learn more in Sour Lake produces Texaco.

March 7, 2007 – National Artificial Reef Plan updated

The National Marine Fisheries Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), approved a comprehensive update of the 1985 National Artificial Reef Plan, popularly known as the “rigs to reefs” program.

A typical platform provides almost three acres of feeding habitat for thousands of species. Photo courtesy U.S. Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

The agency worked with interstate marine commissions and state artificial reef programs, “to promote and facilitate responsible and effective artificial reef use based on the best scientific information available.” The revised National Artificial Reef Plan included guidelines for converting old platforms into reefs. A typical four-leg structure provides up to three acres of habitat for hundreds of marine species.

“As of December 2021, 573 platforms previously installed on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf have been reefed in the Gulf of Mexico,” according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

Learn more in Rigs to Reefs.

March 9, 1930 – Prototype Oil Tanker is Electrically Welded

The world’s first electrically welded commercial vessel, the Texas Company (later Texaco) tanker M/S Carolinian, was completed in Charleston, South Carolina. The World War I shipbuilding boom encouraged new electric welding technologies. The oil company’s 226-ton vessel was a prototype designed by naval architect Richard Smith.

Construction of M/S Carolinian began in 1929. The M/S designation meant it used an internal combustion engine. Photo courtesy Z.P. Liollio.

The tanker — the first electrically welded ship — eliminated the need for about 85,000 pounds of rivets, according to a 2017 article for the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH). Success of the prototype led to “the standard of welded hulls and internal combustion engines would become universal in construction of new vessels.”

March 9, 1959 – Barbie is a Petroleum Doll

Mattel revealed the Barbie Doll at the American Toy Fair in New York City. More than one billion “dolls in the Barbie family” have been sold since. Eleven inches tall, Barbie owes her existence to petroleum products and the science of polymerization, including several plastic acronyms: ABS, EVA, PBT, and PVC.

Petroleum-based polymers are part of Barbie’s DNA.

Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene (ABS) is known for strength and flexibility. This thermoplastic polymer is used in Barbie’s torso to provide impact and heat resistance. EVA (Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate), a copolymer made up of ethylene and vinyl acetate, protects Barbie’s smooth surface.

The Mattel doll also includes Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT), a thermoplastic polymer often used as an electrical insulator. A mineral component facilitates PBT injection molding of her “full figure,” according to the company. Barbie’s hair and many of her designer outfits are made from the world’s first synthetic fiber, nylon, invented in 1935 (see Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer and more articles in Petroleum Products).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); History of Paola, Kansas (1956); Where it all began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio

(1956); Where it all began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio (1994); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma

(1994); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma (2013); Kettles and Crackers – A History of Wyoming Oil Refineries

(2013); Kettles and Crackers – A History of Wyoming Oil Refineries (2016); Utah Oil Shale: Science, Technology, and Policy Perspectives

(2016); Utah Oil Shale: Science, Technology, and Policy Perspectives (2016); George P. Mitchell: Fracking, Sustainability, and an Unorthodox Quest to Save the Planet (2019); Sour Lake, Texas: From Mud Baths to Millionaires, 1835-1909

(2016); George P. Mitchell: Fracking, Sustainability, and an Unorthodox Quest to Save the Planet (2019); Sour Lake, Texas: From Mud Baths to Millionaires, 1835-1909 (1995); Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs

(1995); Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs (1987); Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century Hardcover

(1987); Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century Hardcover (1996); American Fads

(1996); American Fads (1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 12, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Reports of a “mineral tar” from the 1840s helped H.L. Hunt discover an oilfield a century later.

Swallowing “tar pills” supposedly had been curing ills since the mid-1800s, but Alabama’s petroleum industry officially began in 1944 with a Choctaw County well drilled by a well-known Texas wildcatter. On February 17, independent producer Haroldson Lafayette “H.L” Hunt completed his Jackson No. 1 well after discovering Alabama’s first oilfield.

H.L. Hunt had found success in the earliest Arkansas oilfields of the 1920s and even greater success in the East Texas oilfield of the 1930s. He now had revealed the Gilbertown oilfield of western Alabama, about 50 miles southeast of Meridian, Mississippi.

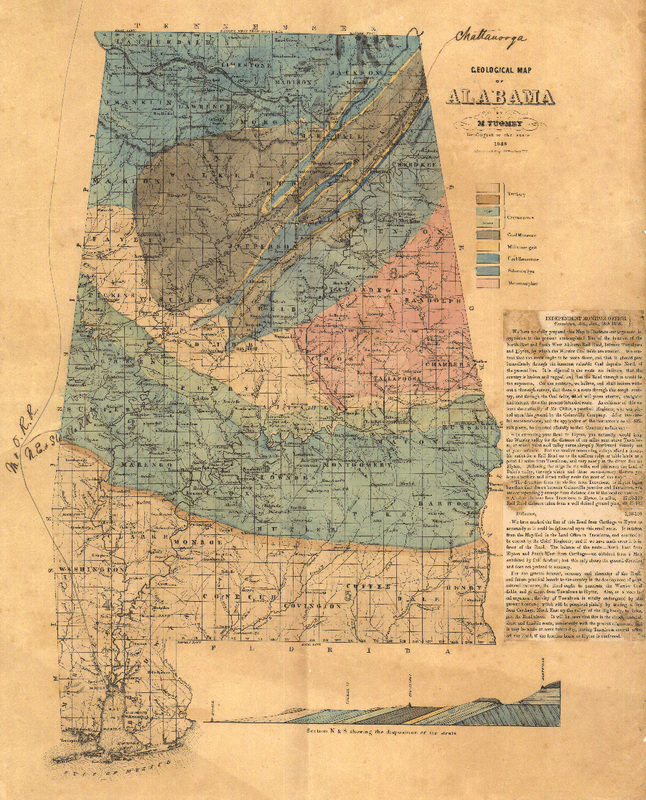

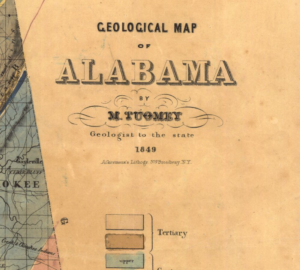

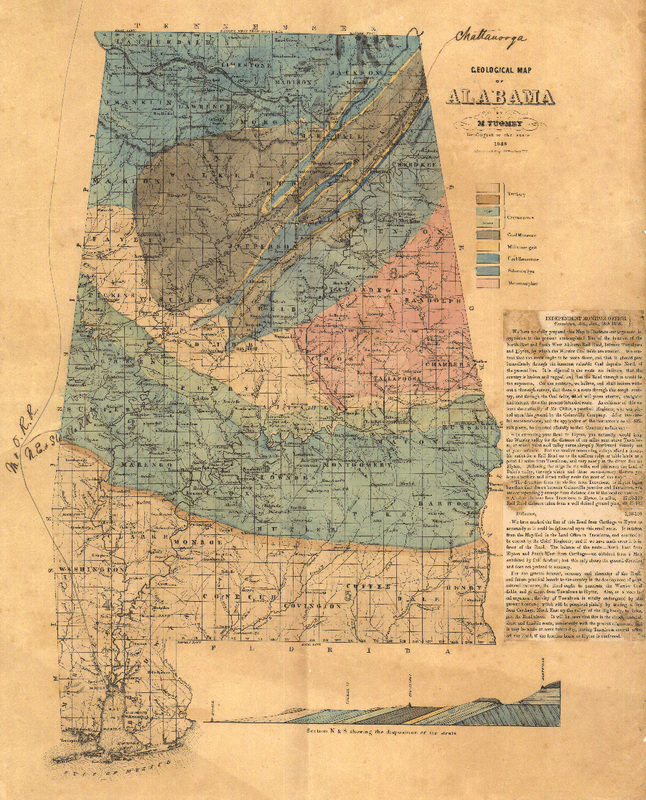

Geological Map of Alabama, printed in 1849 by Michael Tuomey, professor of geology, mineralogy and agricultural chemistry at the University of Alabama. Tuomey published his First Biennial Report of the Geology of Alabama in 1850. Map courtesy University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections.

Despite limited knowledge of the state’s geology, regions with oil and natural gas seeps had attracted interest as early as the mid-19th century. Before Hunt’s Choctaw County wildcat well, 350 dry holes had been drilled in Alabama.

Geologist and petroleum historian Ray Sorenson has investigated the earliest reports of petroleum in all producing states. By the early 2020s, his ongoing project documented the first signs of oil in the United States, Canada, and many parts of the world (see Exploring Earliest Signs of Oil).

In Alabama’s case, Sorenson uncovered an account by an early expert in the scientific field of geology. The first Alabama state geologist, Michael Tuomey, described reports of a “mineral tar,” and cited an 1840s account of finding natural oil seeps six miles from Oakville in Lawrence County.

With quantities of oil and water emerging from a crevice in limestone, Tuomey observed that “the tar, or bitumen, floats on the surface, a black film very cohesive and insoluble in water.”

The A.R. Jackson No. 1 well in 1944 revealed an Alabama oilfield near the Mississippi border. Photo courtesy Hunt Oil Company.

Similar to “Kentucky oil,” Alabama’s Lawrence County oil became popular for its medicinal qualities. Oil from the county was claimed to be “a known cure for Scrofula, Cancerous Sores, Rheumatism, Dyspepsia,” and other diseases.

“Patients visiting the Spring find the tar taken and swallowed as pills, the most efficient form of the remedy,” Tuomey quoted the observation from “Tar Spring of Lawrence” in the 1858 Second Biennial Report On the Geology of Alabama (published one year after his death).

Tuomey served as the state geologist of South Carolina from 1844 to 1847, and as the first state geologist of Alabama from 1848 until his death in 1857. His Geological Map of Alabama was printed in 1849.

In addition to oil, traces of natural gas were discovered in Alabama in the late 1880s, and by 1902, natural gas was being supplied to Huntsville and the town of Hazel Green, according to Alabama historian Alan Cockrell.

“In 1909, a small discovery by Eureka Oil and Gas at Fayette fueled that city’s streetlights for a time, but no natural gas was recovered anywhere in the state for several decades afterward,” he added. Learn about the earliest oilfield discoveries in other producing states in First Oil Discoveries.

Gilbertown Oil Discovery

According to Cockrell, Alabama’s oil and natural gas industry did not truly begin until H.L. Hunt of Dallas, Texas, drilled in Choctaw County near the Mississippi border and discovered the Gilbertown oilfield.

Concrete foundations are all that remains of Alabama’s first oil well, the A.R. Jackson Well No. 1, completed in 1944 near Gilbertown. Photo courtesy Explore Rural S.W. Alabama.

After five weeks of drilling, the well was completed on February 17, 1944, at 2,585 feet in the Selma chalk of the Upper Cretaceous. Hunt’s A.R. Jackson Well No. 1 two miles southwest of downtown Gilbertown had reached a total depth of 5,380 feet before being “plugged back” to its most productive oil-producing geologic formation.

H.L. Hunt’s first Alabama oil well produced just 30 barrels of oil a day, but launched the state’s petroleum industry. “The discovery of this well led to the creation of the State Oil and Gas Board of Alabama in 1945, and to the development and growth of the petroleum industry in Alabama,” notes an Alabama historic marker erected at the site.

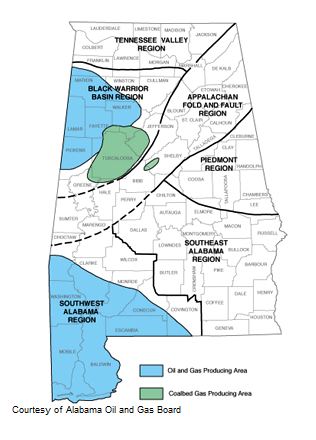

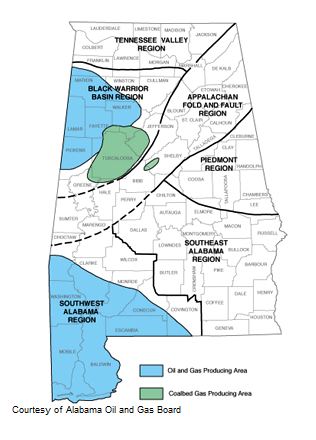

Deeper drilling led to more Alabama petroleum discoveries in the 1980s. Map courtesy Encyclopedia of Alabama.

The first oilfield would produce 15 million barrels of oil, “not a lot by modern standards but enough to make ‘oil fever’ spread rapidly,” Cockrell noted in “Oil and Gas Industry in Alabama” in 2008. The search for another oilfield took 11 more years.

The 1955 oil discovery at Citronelle, a town above a geologic salt dome, finally launched a new drilling boom; five new Alabama oilfields were discovered by 1967. Mobil Oil Company drilled Alabama’s first successful offshore natural gas well in 1981.

As production technologies advance, geologists believe opportunities exist in the “hard shales of the deep Black Warrior Basin beneath Pickens and Tuscaloosa counties and in the thick fractured shales of St. Clair and neighboring counties,” according to Cockrell.

By 2022, more than 17,500 oil and natural gas wells had been drilled in Alabama since the state’s first commercial oil discovery in 1944. According to the Washington, DC-based Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA), about 10 percent of the Alabama wells produced oil, 59 percent natural gas, and 30 percent (about 5,000 wells) were nonproductive.

Mapping Mineral Riches

From the journal Cartographic Perspectives of the North American Cartographic Information Society (NACIS):

Settlement of the newly available land enabled Alabama to move rapidly from being a part of the Mississippi Territory to its own Alabama Territory, and finally to statehood in 1819. The favorable climate and rich soil brought large plantations and slavery.

Appointed State Geologist of Alabama in 1848, Michael Tuomey served until his death in 1857.

Michael Tuomey (1805-1857), professor of geology at the University of Alabama in the 1840s, had attempted to lead Alabama’s economy away from slavery-based agriculture. In 1849, he produced the first survey of the state’s mineral wealth. His map Geological map of Alabama showed exactly where the state’s natural riches were located. The efforts of Tuomey and others were rejected, as were similar efforts in other southern states.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide (2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

(2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Alabama Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-alabama-oil-well. Last Updated: February 12, 2025. Original Published Date: October 21, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 6, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

January 7, 1864 – Oilfield Discovery at Pithole Creek –

The once famous Pithole Creek oilfield was discovered in Pennsylvania with the United States Petroleum Company’s well reportedly located using a witch-hazel dowser. The discovery well, which initially produced 250 barrels of oil a day, brought a “black gold” rush as boom town Pithole made headlines five years after the first U.S. oil well drilled at nearby Titusville.

oilfield was discovered in Pennsylvania with the United States Petroleum Company’s well reportedly located using a witch-hazel dowser. The discovery well, which initially produced 250 barrels of oil a day, brought a “black gold” rush as boom town Pithole made headlines five years after the first U.S. oil well drilled at nearby Titusville.

Boom town Pithole City’s history is preserved at Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek State Park. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Adding to the boom were Civil War veterans eager to invest in the new industry. Newspaper stories added to the oil fever — as did the Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny.” Tourists today visit Oil Creek State Park and its education center on the grassy expanse that was once Pithole.

January 7, 1905 – Humble Oilfield Discovery rivals Spindletop

C.E. Barrett discovered the Humble oilfield in Harris County, Texas, with his Beatty No. 2 well, which brought another Texas drilling boom four years after Spindletop launched the modern petroleum industry. Barrett’s well produced 8,500 barrels of oil per day from a depth of 1,012 feet.

The population of Humble jumped from 700 to 20,000 within months as production reached almost 16 million barrels of oil, the largest in Texas at the time. The field directly led to the 1911 founding of the Humble Oil Company by a group that included Ross Sterling, a future governor of Texas.

An embossed postcard circa 1905 from the Postal Card & Novelty Company, courtesy the University of Houston Digital Library.

“Production from several strata here exceeded the total for fabulous Spindletop by 1946,” notes a local historic marker. “Known as the greatest salt dome field, Humble still produces and the town for which it was named continues to thrive.” Another giant oilfield discovery in 1903 at nearby Sour Lake helped establish the Texaco Company.

Humble Oil, renamed Humble Oil and Refining Company in 1917, consolidated operations with Standard Oil of New Jersey two years later, eventually leading to ExxonMobil.

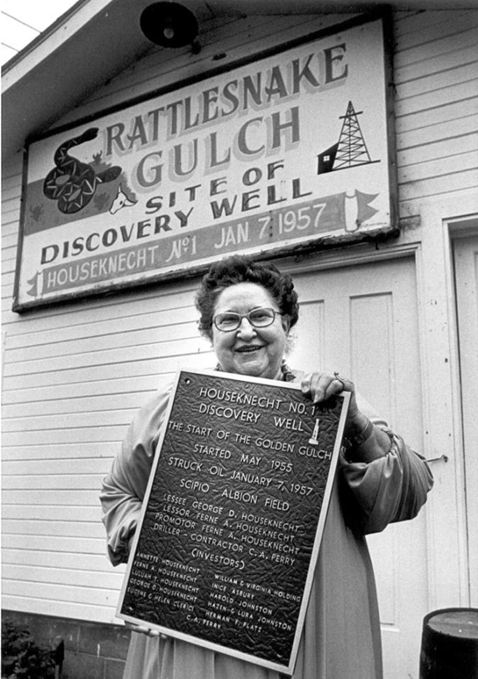

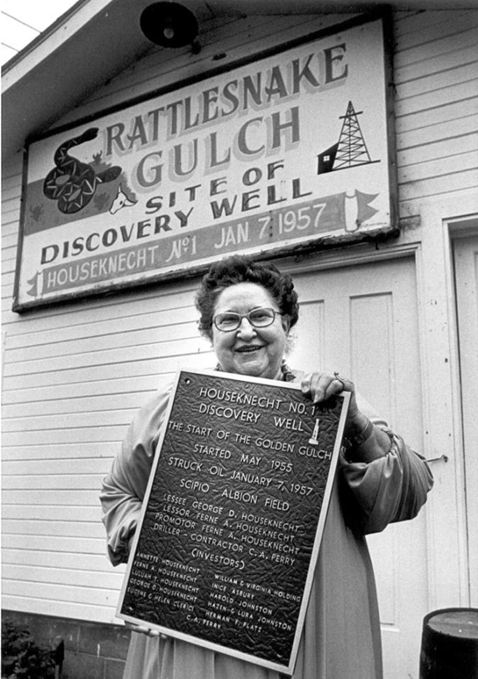

January 7, 1957 – Michigan Dairy Farmer finds Giant Oilfield

After two years of drilling, a wildcat well on Ferne Houseknecht’s Michigan dairy farm discovered the state’s largest oilfield. The 3,576-foot-deep well produced from the Black River formation of the Trenton zone.

After 20 months of on-again, off-again drilling, Ferne Houseknecht’s well revealed a giant oilfield in the southern Michigan basin.

The Houseknecht No. 1 discovery well at Rattlesnake Gulch revealed a producing region 29 miles long and more than one mile wide. It prompted a drilling boom that led to production of 150 million barrels of oil and 250 billion cubic feet of natural gas from the giant Albion-Scipio field in the southern Michigan basin.

“The story of the discovery well of Michigan’s only ‘giant’ oilfield, using the worldwide definition of having produced more than 100 million barrels of oil from a single contiguous reservoir, is the stuff of dreams,” noted Michigan historian Jack Westbrook in 2011.

in 2011.

Learn more in Michigan’s “Golden Gulch” of Oil.

January 7, 1913 – “Cracking” Patent improves Refining

William Burton of the Standard Oil Company’s Whiting, Indiana, refinery received a patent for a process that doubled the amount of gasoline produced from each barrel of oil refined. Burton’s invention came as gasoline demand was rapidly growing with the popularity of automobiles. His thermal cracking concept was an important refining advancement, although the process would be superseded by catalytic cracking in 1937.

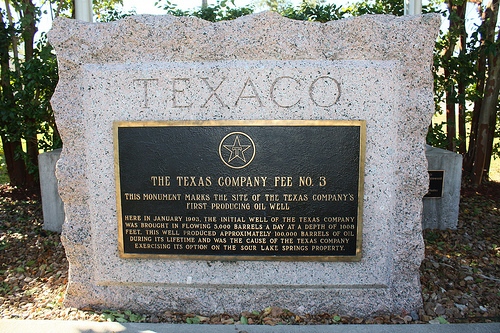

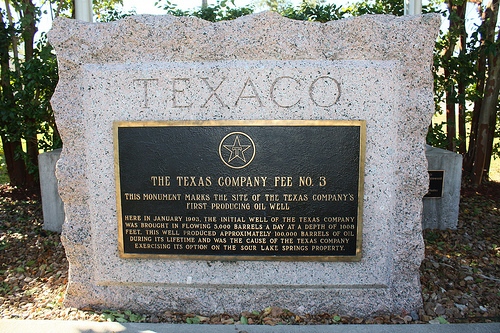

January 8, 1903 – Sour Lake discovery leads to Texaco

Founded a year earlier in Beaumont, Texas, the Texas Company struck oil with its Fee No. 3 well, which flowed at 5,000 barrels a day, securing the company’s success in petroleum exploration, production, transportation and refining.

A monument marks the site where the Fee No. 3 well flowed at 5,000 barrels of oil a day in 1903, helping the Texas Company become Texaco.

“After gambling its future on the site’s drilling rights, the discovery during a heavy downpour near Sour Lake’s mineral springs, turned the company into a major oil producer overnight, validating the risk-taking insight of company co-founder J.S. Cullinan and the ability of driller Walter Sharp,” explained a Texaco historian. The Sour Lake field — and wells drilled in the Humble oilfield two years later — led to the Texas Company becoming Texaco (acquired by Chevron in 2001).

Learn more in Sour Lake produces Texaco.

January 10, 1870 – Rockefeller incorporates Standard Oil Company

John D. Rockefeller and five partners incorporated the Standard Oil Company in Cleveland, Ohio. The new oil and refining venture immediately focused on efficiency and growth. Instead of buying barrels, the company bought tracts of oak timber, hauled the dried timber to Cleveland on its own wagons, and built its own 42-gallon oil barrels.

A stock certificate issued in 1878 for Standard Oil Company, which would become Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio) following the 1911 breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s oil monopolies.

Standard Oil’s cost per wooden barrel dropped from $3 to less than $1.50 as the company improved refining methods to extract more kerosene per barrel of oil (there was no market for gasoline). By purchasing properties through subsidiaries, dominating railroads and using local price-cutting, Standard Oil captured 90 percent of America’s refining capacity.

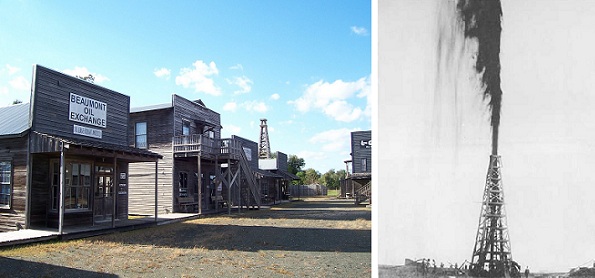

January 10, 1901 – Spindletop launches Modern Petroleum Industry

The modern U.S. oil and natural gas industry began 123 years ago on a small hill in southeastern Texas when a wildcat well erupted near Beaumont. The Spindletop field, which yielded 3.59 million barrels of oil by the end of 1901, would produce more oil in one day than all the rest of the world’s oilfields combined.

The Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum in Beaumont, Texas, opened in 1976 to educate visitors about the importance of the 1901 “Lucas Gusher.”

The “Lucas Gusher” and other nearby discoveries changed American transportation by providing abundant oil for cheap gasoline. The drilling boom would bring hope to a region devastated just a few months earlier by the Galveston Hurricane, still the deadliest in U.S. history. Petroleum production from the well’s geologic salt dome had been predicted by Patillo Higgins, a self-taught geologist and Sunday school teacher.

Learn more in Spindletop launches Modern Petroleum Industry.

January 10, 1919 – Elk Hills Oilfield discovered in California

Standard Oil of California discovered the Elk Hills field in Kern County, and the San Joaquin Valley soon ranked among the most productive oilfields in the country. It became embroiled in the 1920s Teapot Dome lease scandals and yielded its billionth barrel of oil in 1992. Visit the petroleum exhibits of the Kern County Museum in Bakersfield and at the West Kern Oil Museum in Taft.

January 10, 1921 – Oil Boom arrives in Arkansas

“Suddenly, with a deafening roar, a thick black column of gas and oil and water shot out of the well,” noted one observer in 1921 when the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well struck oil near El Dorado, Arkansas. H.L. Hunt would soon arrive from Texas (with $50 he had borrowed) and join lease traders and speculators at the Garrett Hotel — where fortunes were soon made and lost. “Union County’s dream of oil had come true,” reported the local paper. The giant Arkansas field would lead U.S. oil output in 1925 with production reaching 70 million barrels.

Learn more in First Arkansas Oil Wells.

January 11, 1926 – “Ace” Borger discovers Oil in North Texas

Thousands rushed to the Texas Panhandle seeking oil riches after the Dixon Creek Oil and Refining Company completed its Smith No. 1 well, which flowed at 10,000 barrels a day in southern Hutchinson County. A.P. “Ace” Borger of Tulsa, Oklahoma, had leased a 240-acre tract. By September, the Borger oilfield was producing more than 165,000 barrels of oil a day.

A downtown museum exhibits Borger’s oil heritage. Photo by Bruce Wells.

After establishing his Borger Townsite Company, Borger laid out streets and sold lots for the town, which grew to 15,000 residents in 90 days. When the oilfield produced large amounts of natural gas, the town named its minor league baseball team the Borger Gassers. The team left the league in 1955 (owners blamed air-conditioning and television for reducing attendance).

Dedicated in 1977, the Hutchinson County Boom Town Museum in Borger celebrates “Oil Boom Heritage” every March.

January 12, 1904 – Henry Ford sets Speed Record

Seeking to prove his cars were built better than most, Henry Ford set a world land speed record on a frozen Michigan lake. At the time his Ford Motor Company was struggling to get financial backing for its first car, the Model T. It was just four years after America’s first auto auto show.

The Ford No. 999 used an 18.8 liter inline four-cylinder engine to produce up to 100 hp. Image courtesy Henry Ford Museum.

Ford drove his No. 999 Ford Arrow across Lake St. Clair, which separates Michigan and Ontario, Canada, at a top speed of 91.37 mph. The frozen lake “played an important role in automobile testing in the early part of the century,” explained Mark DIll in “Racing on Lake St. Clair” in 2009. “Roads were atrocious and there were no speedways.”

Learn about a 1973 natural gas-powered world land speed record in Blue Flame Natural Gas Rocket Car.

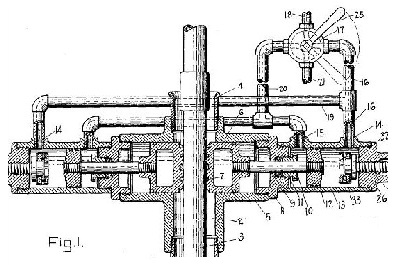

January 12, 1926 – Texans patent Ram-Type Blowout Preventer

Seeking to end dangerous and wasteful oil gushers, James Abercrombie and Harry Cameron patented a hydraulic ram-type blowout preventer (BOP). About four years earlier, Abercrombie had sketched out the design on the sawdust floor of Cameron’s machine shop in Humble, Texas. Petroleum companies embraced the new technology, which would be improved in the 1930s.

James Abercrombie’s design used hydrostatic pistons to close on the drill stem. His improved blowout preventer set a new standard for safe drilling

First used during the Oklahoma City oilfield boom, the BOP helped control production of the highly pressurized Wilcox sandstone (see World-Famous “Wild Mary Sudik”). The American Society of Mechanical Engineers recognized the Cameron Ram-Type Blowout Preventer as an “Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark” in 2003.

Learn more in Ending Oil Gushers – BOP.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Humble, Images of America (2013); Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund 1976-2011: A 35-year Michigan Oil and Gas Industry Investment Heritage in Michigan’s Public Recreation Future

(2013); Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund 1976-2011: A 35-year Michigan Oil and Gas Industry Investment Heritage in Michigan’s Public Recreation Future (2011); Handbook of Petroleum Refining Processes

(2011); Handbook of Petroleum Refining Processes (2016); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

(2016); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas, in 1901

(2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas, in 1901 (2008); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2008); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford

(1982); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford (2014); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

(2014); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language (2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

(1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.