Industry executives in 1968 recognized the public relations value of LNG fueling a land speed record.

Proclaiming natural gas “the fuel of the future,” the American Gas Association sponsored a sleek rocket car powered by liquified natural gas (LNG) that in October 1970 set a world land speed record that would remain unbroken for more than a decade.

In 1882, Mrs. Karl Benz secretly took her husband’s “Model III Patent Motorwagen” on a 65-mile road trip at an average speed of four mph. The public relations stunt took 15 hours.

The LNG rocket-powered Blue Flame set a world land speed record of 630.388 mph on October 23, 1970, at the Bonneville Salt Flats.

By 1900, electric vehicles were competing with the steam and internal combustion engines (see Cantankerous Combustion — First U.S. Auto Show).

The land speed record came to the United States in 1904, “when Henry Ford wanted to prove to the world that his cars were built better than anyone else’s,” noted a speed-record historian in Australia.

The Ford No. 999 used an 18.8-liter inline four-cylinder engine that produced up to 100 horsepower. Image courtesy Henry Ford Museum.

On January 12 at Lake St. Clair, Michigan, near Detroit, Ford bounced his Ford Arrow across the frozen lake to reach an average speed of 91.37 mph. He remarked of the run, after retirement, that it had scared him so badly that he never again wanted to climb into a racing car.

“The No. 999, little more than a giant engine encased in a wood frame with a seat and a metal bar for steering, thundered across the lake,” reported auto historian Cameron Rogers in 2013. When news of Ford’s record spread around the country, his new car company got a boost for becoming one of the most successful auto manufacturers in history.

By the 1920s, as gasoline engine technologies evolved, high-octane but dangerous enhancers like tetraethyl lead were adopted (and are still used in aviation fuel).

On the ground, with engine efficiency advancements, competition intensified for a world land speed record as kerosene powered blistering new milestones. In the fall of 1970, a streamlined, blue feat of engineering set the coveted record fueled by liquified natural gas.

Natural Gas Rocket Car

The Blue Flame, powered by liquefied natural gas (LNG) and hydrogen peroxide, reached 630.388 miles per hour on October 23, 1970 — and had the potential of going even faster. As the petroleum industry called natural gas “the fuel of the future,” the rocket car’s speed record remained unbroken until 1983.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) fueled a homemade, 38-foot rocket car to a world land speed record in October 1970.

Throughout the 20th century, land speed records were set with vehicles powered by steam, electricity, and all kinds of petroleum distillates. National pride was often at stake as British, American, French, Belgian, German, and Italian teams fielded competing machines.

The world’s first land speed record was set in 1898 by Frenchman Count Gaston De Chasseloup-Laubat, driving an electric-powered car. He achieved 39.24 mph.

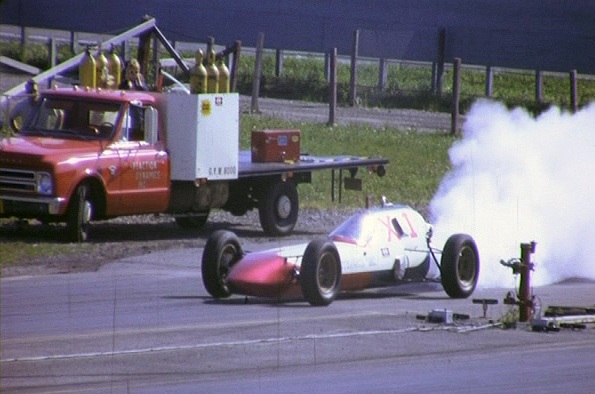

Richard Keller and a small group of engineering students tested the Blue Flame chassis and wheel design (photo from 8-mm Keller home movie).

After decades of traditional internal combustion fueled records, mainly by the British, by the 1960s, American aviation technology took mankind’s need for speed to a new level. Jet engines began pushing the land record to previously unthinkable levels.

Jet Propellant Four (JP-4), the U.S. Air Force’s primary fuel until the late 1990s, offered a powerful blend of kerosene and naphtha. On Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats in 1963, the fuel proved to be as good on the ground as it was in the air.

In August 1963, the Spirit of America, a radical new design created by Craig Breedlove, used a $500 surplus jet engine that burned this kerosene-based JP-4 to run 407.45 mph. Breedlove’s jet-powered machine brought the land speed record back to the United States from England after an absence of more than 30 years.

However, just nine months later, Art Arfons, a drag racer from Ohio, took the land record after clocking 434 mph with his Green Monster using JP-4 in an afterburner-equipped jet engine.

Not to be outdone, Breedlove soon returned to Bonneville with his Spirit of America and pushed to a new record of 526 mph. Arfons in turn responded with a run 10 mph faster. And so it went over three years of competition.

Breedlove’s Spirit of America Sonic 1 ultimately triumphed over Arfons’ Green Monsters and exceeded 600 mph to set a record that would not be bested until 1970 — when natural gas made its spectacular rocket fuel debut at Bonneville.

X-1 Rocket Dragster

The Blue Flame sprang from the imaginations of three Milwaukee, Wisconsin, men with a passion for speed: Dick Keller, Ray Dausman and later Pete Farnsworth. In the summer of 1964, Keller, employed by the Chicago-based Illinois Institute of Technology Research Institute, became friends with Dausman, who was working on a propellant research contract for NASA.

“Around this time, a keen amateur hot-rodder called Dick Keller had just got married,” noted a June 2011 article in Octane magazine. “As a condition of accepting his proposal, his new wife insisted he give up drag racing. But he didn’t lose his interest in fast cars.”

Drag race records set by the X-1 dragster and its 2,500 pounds of thrust rocket motor inspired scaling up to a 22,500-pound thrust engine using liquefied natural gas (LNG) and hydrogen peroxide.

The article explained that Keller and Dausman often lunched together. After sharing many “wild engineering ideas” and concepts, “We were scribbling on napkins and stuff — then we thought we would look at a rocket-powered dragster,” Keller was quoted.

The pair designed, built and successfully tested a small prototype rocket motor giving 25 pounds of thrust. As they prepared a larger version, Keller designed a chassis, and “they drafted in part-time hot rod builder Pete Farnsworth to help,” noted the Octane article. The speed enthusiasts also formed a company, Reaction Dynamics Inc.

In April 1967, the rocket to propel dragster X-1 was complete. The motor delivered 2,500 pounds of thrust using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizer for an LNG propellant. “This showed well on the drag strips and within a season was outrunning the top-fuelers and jet dragsters,” the article added.

For two months in 1967, the X-1 raced every major turbojet-powered dragster in the nation and produced a lower elapsed time in each race. The record-breaking success of the X-1 dragster and its 2,500-pound thrust rocket enabled Reaction Dynamics to consider scaling up the power using LNG and hydrogen peroxide.

After the X-1’s final speed run in 1968 at the Oklahoma City Dragway, U.S. natural gas industry executives began taking notice.

“When the Breedloves and the Arfonses and so forth were setting records, they had to find a surplus jet engine to do the job,” Keller explained. “With us, we felt all we had to do was decide how much power we needed — we could build a rocket to do it.”

It was about this time that the Institute of Gas Technology (IGT), then the research and development arm of a national association of natural gas companies, saw a PR opportunity. The industry lobbying group recognized the potential of sponsoring a natural gas-fueled attempt at the land speed record.

Blue Flame Project

Keller noted that following the X-1’s final run in September 1968 at the Oklahoma City Dragway, the natural gas industry began taking notice of their work at Reaction Dynamics. The American Gas Association (AGA), headquartered in Washington, D.C., contacted Keller and his team.

“It was a promotion of the safety and usefulness of liquefied natural gas,” noted one of the Blue Flame’s designers.

“We had a big meeting — you can see the guys in the suits,” Keller said later. “These are all gas industry executives there to see firsthand what we could do with the X-1. They agreed at this event to sponsor the Blue Flame officially.”

Keller noted that with the growing environmental movement, AGA executives saw the value of educating consumers. “The Blue Flame was really ‘green’ — it was fueled by clean-burning natural gas and hydrogen peroxide,” he proclaimed. “It was the greenest world land speed record set in the 20th century.”

Although natural gas had long been considered an alternative fuel for the transportation sector, much of the public was unaware of this cleaner power source. “It was a promotion of the safety and usefulness of liquefied natural gas,” Pete Farnsworth explained in a 2007 interview.

Beginning with the American Gas Association in 1968, Dick Keller of Reaction Dynamics convinced the natural gas industry to sponsor an attempt at the world land speed record.

“There were nine graduate engineers working on masters degrees for theses on various aspects of the design of the Blue Flame: structures, dynamics, aerodynamics, wheel design, all sorts of things,” Farnsworth added. About 70 Illinois Institute of Technology undergraduates would also become involved in the final design.

The 38-foot, 6,500-pound Blue Flame was powered by a rocket motor that combined liquefied natural gas and highly purified hydrogen peroxide. The motor could produce 22,500 pounds of thrust — roughly 58,000 horsepower. AGA executives originally budgeted $165,000 for the project.

Although more than $250,000 was ultimately spent, on October 23, 1970, the Blue Flame rewarded its supporters with a new Federation Internationale de l’Automobile official world land speed record of 630.388 mph in the kilometer, 622.407 mph in the mile.

The Blue Flame’s world land speed record stood until the British retook it in 1983 using the turbojet-powered Thrust 2, breaking the mile record. The Blue Flame’s kilometer record, however, remained unbroken until 1997 by Thrust SSC.

The current record, set on October 15, 1997, was set by the United Kingdom’s twin-turbofan JP-4-burning Thrust SSC — Super Sonic Car. Driven by a Royal Air Force pilot, Thrust SSC reached 763 mph — the first land vehicle to break the sound barrier. The Blue Flame could have done that in 1970, according to Keller.

“It was built to go supersonic. We were sure we could get over 800 miles per hour,” Keller said. “We were actually operating at about 13,000 to 14,000 pounds of thrust and we had a 22,500-pound thrust capability. So we really had dialed it back for what was intended to be the first year of a multiyear project.”

Fate of the Flame

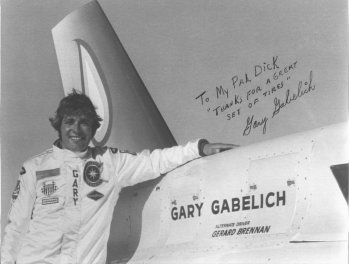

The Blue Flame toured the country following its October 1970 world record, and a lighter, fiberglass version toured Europe. AGA’s natural gas marketing aspirations were met thanks in part to the rocket car’s skilled (and photogenic) driver, Gary Gabelich of Long Beach, California. Gabelich appeared on news, talk and variety television shows — including “The Dating Game.”

The Blue Flame’s driver, Californian Gary Gabelich, promoted natural gas — and appeared on “The Dating Game.”

However, when industry executives, racing enthusiasts, and others made an effort to have the historic natural gas vehicle displayed in a U.S. museum, there were no takers. “Pathetic, since Breedlove’s Spirit of America is in the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry and the Blue Flame’s roots were in Chicago, and it was built in Milwaukee,” lamented Dick Keller.

Overlooked by American museums in the early 1970s, the Blue Flame today is on permanent exhibit in Germany’s Sinsheim Auto and Technik Museum, near Heidelberg.

“The car was purchased for a song ($10,000) by a private collector in Europe, then later acquired by the museum in Sinsheim (Germany),” Keller added. “Because it was the first to exceed 1,000 kilometers per hour, it was a bigger sensation in Europe than in the U.S.A.”

Historical Society Video

Interviewed by the American Oil & Gas Historical Society in 2013, Keller explained that with the growing environmental movement of the late 1960s, AGA “suits” saw value in educating consumers about natural gas as a fuel. An AOGHS volunteer added details from the interview to a Keller home movie.

American Oil & Gas Historical Society volunteer contributing editor Col. (ret.) Kris Wells, a former USAF filmmaker, interviewed Dick Keller in 2013 and added audio to a 26-minute video from Keller’s original 8-mm color film.

In 2020, natural gas delivered in the United States to end users averaged 75.8 billion cubic feet every day, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

With most natural gas demand coming from electricity generators in the 2010s, natural gas became the fastest-growing fossil fuel, accounting for nearly a quarter of the electricity. In 2024, natural gas accounted for more than 25 percent of the world’s total energy supply and almost 30 percent of global fossil fuel use, reported the International Energy Agency.

Dick Keller in 2020 published Speedquest: Inside the Blue Flame, telling the story of the last American team to set the world land speed record.

The Blue Flame became the world land speed record holder thanks to Reaction Dynamics’ Dick Keller, Pete Farnsworth and Ray Dausman in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and driver Gary Gabelich of Long Beach, California. In September 2020, Keller published Speedquest: Inside the Blue Flame.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Speedquest: Inside the Blue Flame (2020); The Reluctant Rocketman: A Curious Journey in World Record Breaking (2013); The American Highway: The History and Culture of Roads in the United States

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Blue Flame Natural Gas Rocket Car.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/the-blue-flame-natural-gas-rocket-car. Last Updated: October 14, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2009.