by Bruce Wells | Aug 7, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

Phillips Petroleum’s Nu-Aviation Gasoline powered a 1927 record-setting air race to Hawaii.

Hundreds of gallons of high-octane gas refined by Phillips Petroleum Company powered the “Woolaroc” monoplane to victory in a record-setting but deadly air race from California to Hawaii. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Aug 5, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

Bertha Benz’s 65-mile drive in 1888 made headlines for her husband’s fledgling auto company.

German mechanical engineer Karl Friedrich Benz invented and built a three-wheel “motorwagen,” today recognized as the world’s first car. His wife helped steer the company’s first marketing campaign.

Although others had experimented with electric and steam-powered vehicles — and a gasoline-powered engine had been added to a pushcart in 1870 — mechanical engineer (and locksmith) Karl Benz invented the modern car in 1885 when he built his “Fahrzeug mit Gasmotorenbetrieb” (vehicle with gas engine) in Mannheim, Germany. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jun 10, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

North Slope oil began moving through Alaska’s 800-mile pipeline system in 1977.

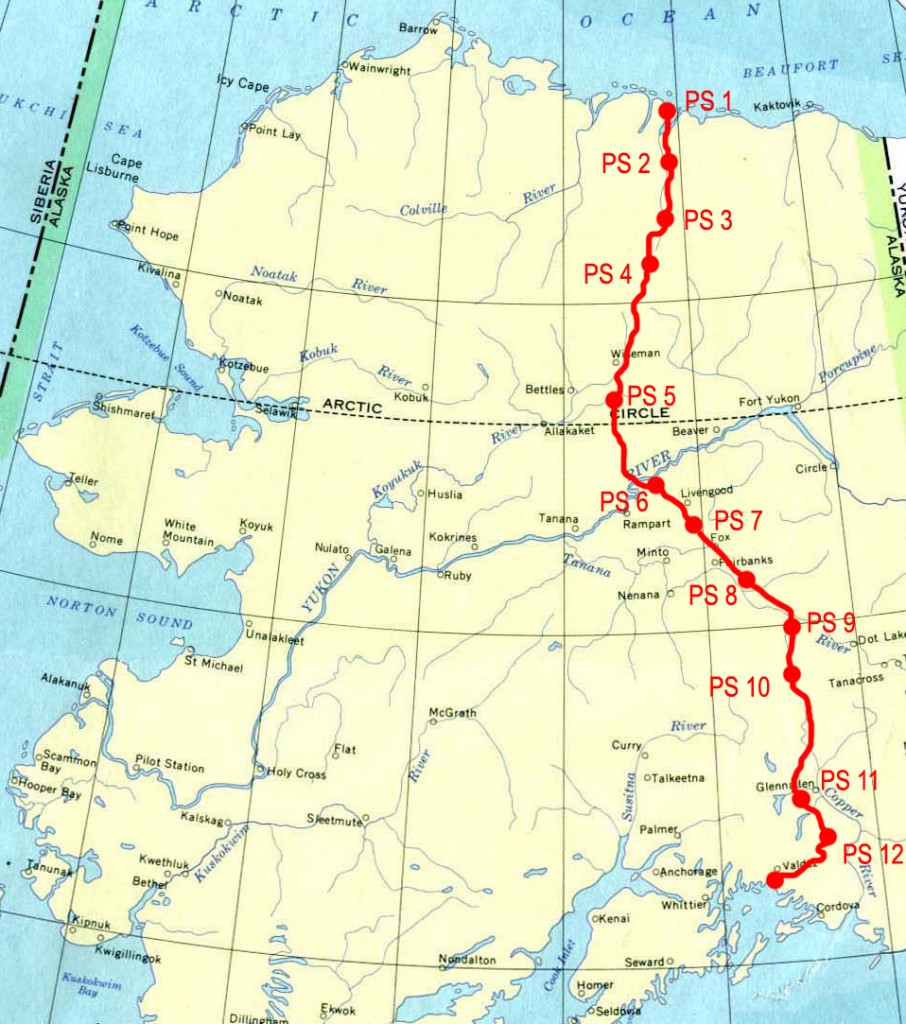

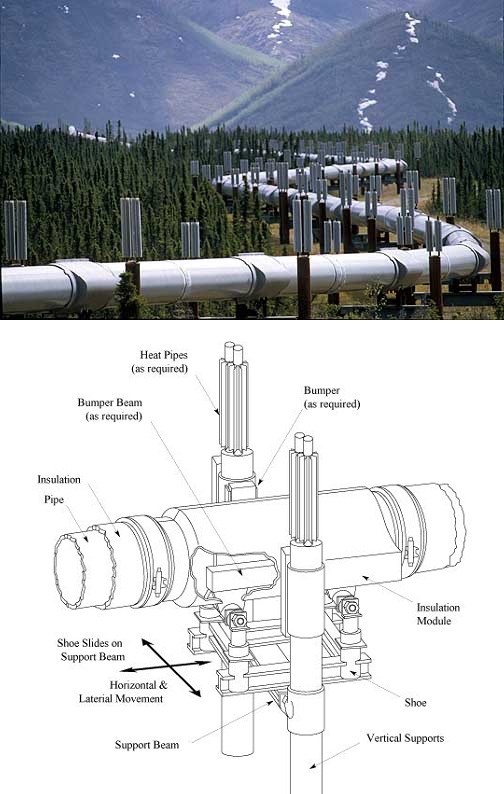

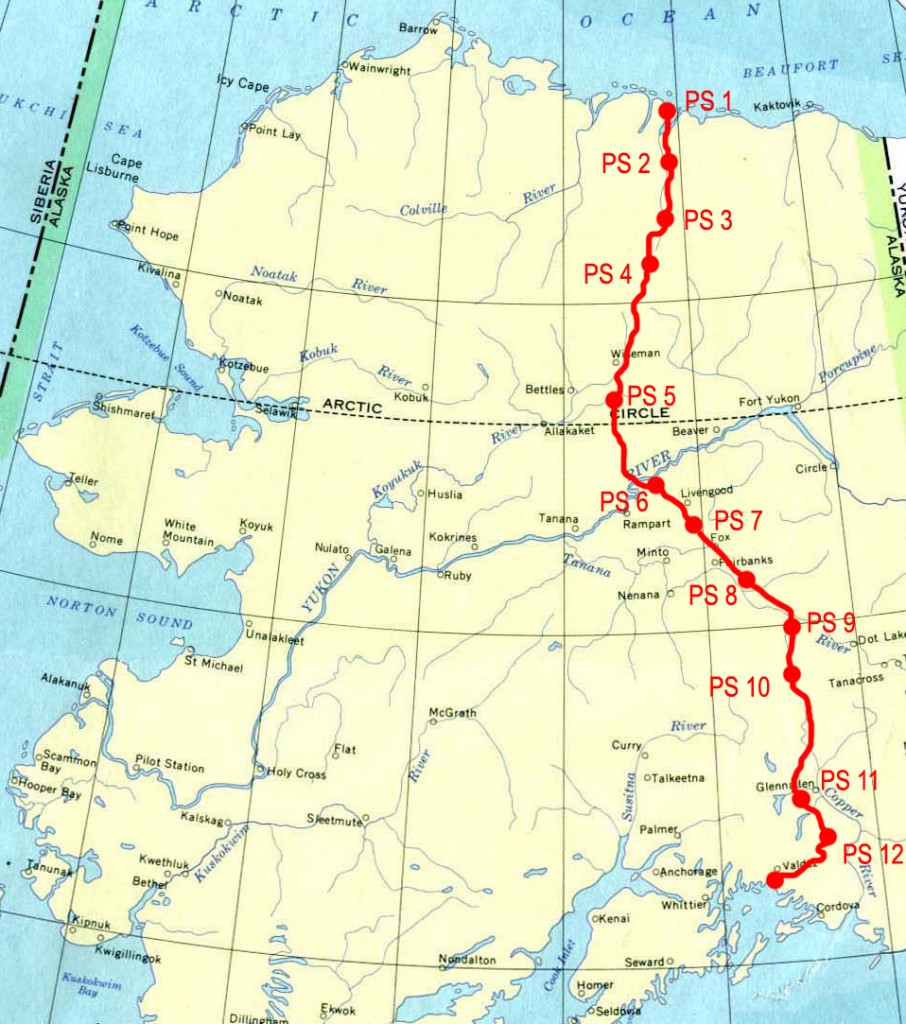

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, designed and constructed to carry billions of barrels of North Slope oil to the port of Valdez, has been recognized as a landmark of engineering. On June 20, 1977, the 800-mile pipeline began carrying oil from Prudhoe Bay oilfields to the Port of Valdez at Prince William Sound. The oil began arriving 38 days later.

In July 1973, a tie-breaking vote by Vice President Spiro Agnew in the U.S. Senate passed the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act after years of debate about the pipeline’s environmental impact. Concerns included spills, earthquakes, and elk migrations.

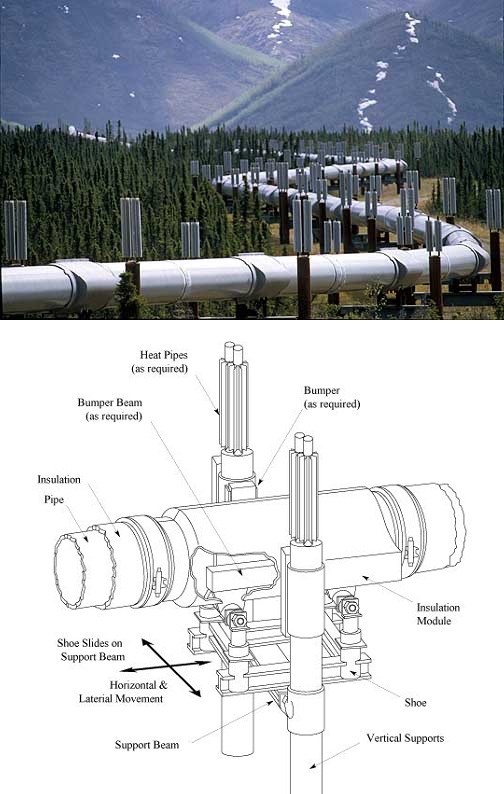

The Alaskan Pipeline system’s 420-miles above ground segments use a zig-zag configuration to allow for expansion or contraction of the pipe.

With the laying of the first section of pipe on March 27, 1975, construction began on what at the time was the largest private construction project in American history.

The 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline system, including pumping stations, connecting pipelines, and the ice-free Valdez Marine Terminal, ended up costing billions. The last pipeline weld occurred on May 31, 1977, and oil from the Prudhoe Bay field began flowing to the port of Valdez on June 20, traveling at four miles an hour through the 48-inch-wide pipe.

The pipeline system cost $8 billion, including terminal and pump stations, and would transport about 20 percent of U.S. petroleum production. Tax revenue earned Alaskans about $50 billion by 2002.

Engineering Milestones

Special engineering was required to protect the environment in difficult construction conditions, according to Alyeska Pipeline Service Company. Details about the pipeline’s history include:

- Oil was first discovered in Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope in 1968.

- Alyeska Pipeline Service Company was established in 1970 to design, construct, operate and maintain the pipeline.

- The state of Alaska entered into a right-of-way agreement on May 3, 1974; the lease was renewed in November of 2002.

- Thickness of the pipeline wall: .462 inches (466 miles) & .562 inches (334 miles).

- The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System crosses the ranges of the Central Arctic heard on the North Slope and the Nelchina Herd in the Copper River Basin.

- The Valdez Terminal covers 1,000 acres and has facilities for crude oil metering, storage, transfer and loading.

- The pipeline project involved some 70,000 workers from 1969 through 1977.

- The first pipe of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System was laid on March 27, 1975. Last weld was completed May 31, 1977.

The Alaskan pipeline brings North Slope production to tankers at the port of Valdez. Map courtesy USGS.

- The pipeline is often referred to as “TAPS” – an acronym for the Trans Alaska Pipeline System.

- More than 170 bird species have been identified along the pipeline.

- First oil moved through the pipeline on June 20, 1977; it took 28 days to arrive at Valdez.

The pipeline delivered oil almost a decade after the Prudhoe Bay oilfield’s discovery. “OMAR” was the Organization for Management of Alaska’s Resources, now the Resource Development Council for Alaska.

- 71 gate valves can block the flow of oil in either direction on the pipeline.

- First tanker to carry crude oil from Valdez: ARCO Juneau, August 1, 1977.

- Maximum daily throughput was 2,145,297 on January 14, 1988.

- The pipeline is inspected and regulated by the State Pipeline Coordinator’s Office.

At the peak of its construction in the fall of 1975, more than 28,000 people worked on the pipeline. There were 31 construction camps built along the route, each built on gravel to insulate and help prevent pollution to the underlying permafrost.

Heaters

The above-ground sections of the pipeline (420 miles) were constructed in a zigzag configuration to allow for expansion or contraction of the pipe because of temperature changes.

Specially designed anchor structures, 700 feet to 1,800 feet apart, securely hold the pipe in position. In warm permafrost and other areas where heat might cause undesirable thawing, the supports contain two, two-inch pipes called “heat pipes.”

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline today has been recognized as a landmark engineering feat. It remains essential to Alaska’s economy.

The first tanker carrying North Slope oil from the new pipeline sailed out of the Valdez Marine Terminal on August 1, 1977. By 2010, the pipeline had carried about 16 billion barrels of oil. Alaska’s total oil production in 2013 was nearly 188 million barrels, or about seven percent of total U.S. production.

The first Alaska oil well with commercial production was completed in 1902 in a region where oil seeps had been known for years. The Alaska Steam Coal & Petroleum Syndicate produced the oil near the remote settlement of Katalla on Alaska’s southern coastline. The oilfield there also led to construction of Alaska Territory’s first refinery.

The modern Alaskan petroleum industry began in 1957 with an oilfield discovery at Swanson River. The next major milestone came when Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) and Exxon discovered the Prudhoe Bay field in March 1968 about 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Rise and Fall of Production

The Prudhoe Bay oilfield proved to be the largest in North America at more than 213,500 acres — exceeding the “Black Giant” East Texas Oilfield discovered in 1930.

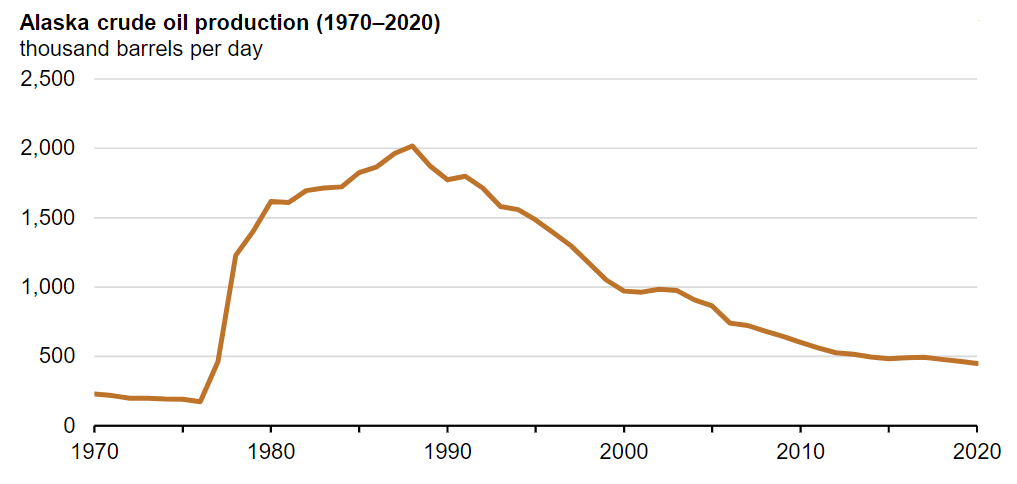

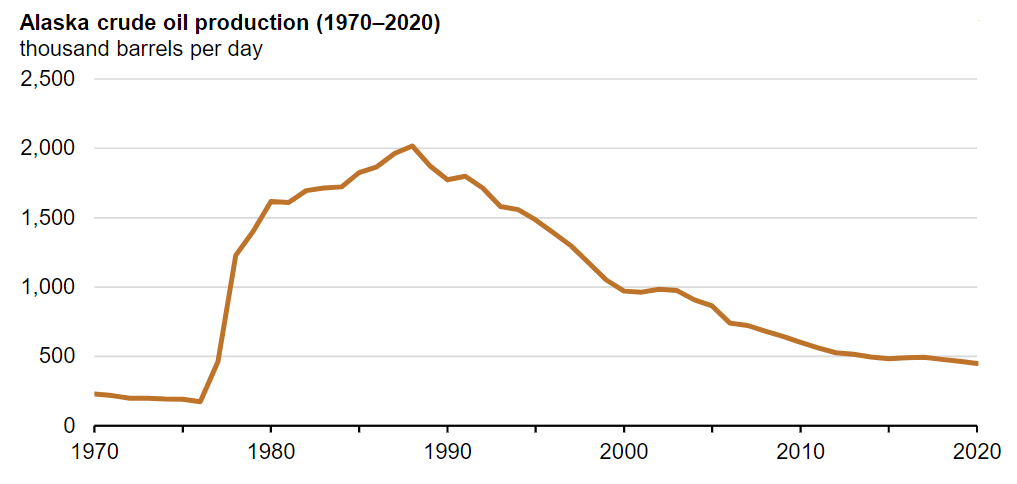

Alaska’s daily oil production peaked in 1988 at about 2 million barrels of oil per day, according to the Department of Energy Energy Information Administration (EIA), Petroleum Supply Monthly.

Annual Alaska oil production peaked in 1988 at 738 million barrels of oil — about 25 percent of U.S. oil production at the time, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). Production averaged about 448,000 barrels of oil per day in 2020, the lowest level in more than 40 years.

“Crude oil production in Alaska averaged 448,000 barrels per day (b/d) in 2020, the lowest level of production since 1976,” the agency noted in its April 2021 Today in Energy report. “Last year’s production was over 75 percent less than the state’s peak production of more than 2 million b/d in 1988.”

The decline in the state’s oil production has decreased deliveries in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, EIA added. Lower oil volumes caused oil to move more slowly in the pipeline, and the travel time from the North Shore to Valdez increased by 18 days in 2020.

For America’s pipeline history during World War II, see Big Inch Pipelines of WW II and PLUTO, Secret Pipelines of WWII.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Great Alaska Pipeline (1988); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier

(1988); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier (1997); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals

(1997); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals (1993); Oil: From Prospect to Pipeline

(1993); Oil: From Prospect to Pipeline (1971). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1971). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Trans-Alaska Pipeline History.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/trans-alaska-pipeline. Last Updated: July 14, 2025. Original Published Date: June 20, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | May 21, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

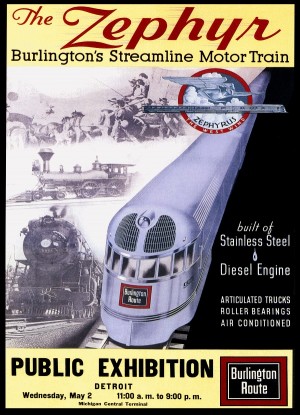

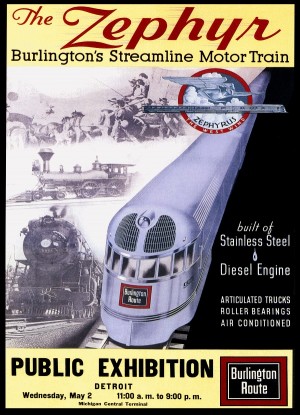

Powered by a diesel-electric engine in 1934, a streamliner cut steam locomotion travel time by half.

“Once I built a railroad, I made it run, made it race against time. Once I built a railroad; now it’s done. Brother, can you spare a dime?” — Bing Crosby, 1932.

By the early 1930s, America’s passenger railroad business was in deep trouble. In addition to the Great Depression, the once-dominant transportation industry faced growing competition from automobiles. New refineries produced vast amounts of gasoline, thanks to giant oilfield discoveries like Spindletop Hill in Texas.

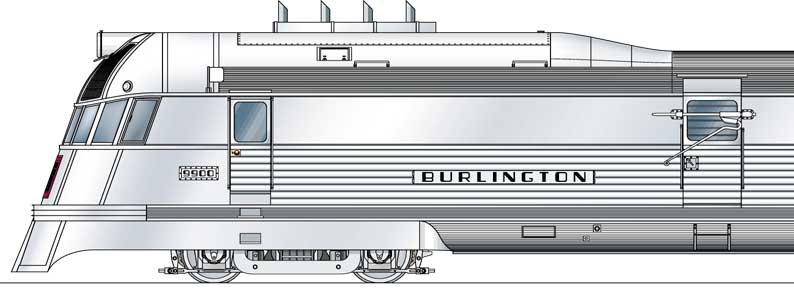

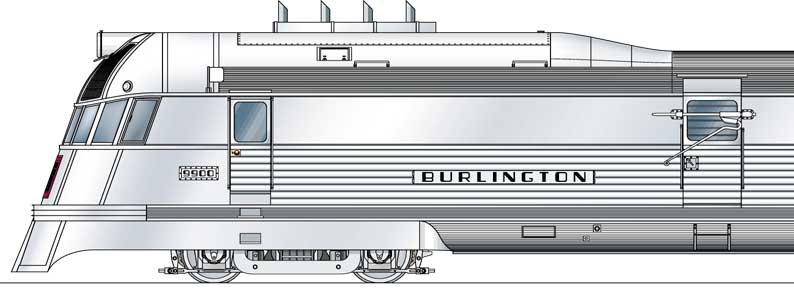

Diesel-electric engines pioneered by General Motors and Winton Engine Company saved America’s railroad passenger industry with a four-fold power-to-weight gain. Photo courtesy Model Railroader magazine, January 1999.

Despite the hard economic times, gasoline fueled more than 30 million cars, trucks, and buses on U.S. roads (many without asphalt paving).

Locomotive Power

Primitive diesel engines of the day remained heavy and slow, but a powerful railroad diesel-electric engine was in the future. It had been 60 years since coal-burning steam locomotives and the transcontinental railroad had linked America’s east and west coasts on May 10, 1869.

Used since about 1925, diesel engines were heavy — producing only a single horsepower from 80 pounds of engine weight.

Meanwhile, railroad steam engine technology had advanced since the “golden spike” of 1869 in Promontory Point, Utah. But locomotives still “belched steam, smoke, and cinders,” noted one railroad historian, adding, “Passengers often felt like they had been on a tour of a coal mine.”

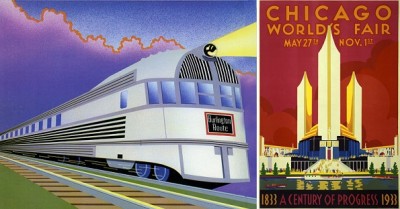

The two streamliner trains that changed America’s railroad industry in the late 1930s: Union Pacific M-10000 (left) and Burlington Zephyr. The Zephyr has been preserved as an exhibit at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Photo courtesy Union Pacific Museum.

While most U.S. locomotives were still steam-powered, General Electric in 1913 designed and built the first commercially successful gasoline-powered engine locomotive. Two General Motors 175-horsepower V-8s powered two 600-volt, direct current generators. They propelled the 57-ton locomotive to a top speed of 51 miles per hour.

The locomotive Dan Patch, considered by many to be the first successful internal combustion engine locomotive in the United States.

The Electric Line of Minnesota Company purchased the new gasoline-powered electric hybrid for $34,500. Marketing executives picked the name Dan Patch. a world-champion harness horse at the time. By 1930, powerful diesel engines with electric generators transformed train travel with streamliners.

Distillate Engines

In rail yards, low-geared diesels had been used from about 1925, mainly as engines for “switcher” locomotives used for maneuvering, but they were slow, according to historian Richard Cleghorn Overton. Powerful distillate-burning engines proved heavy and difficult to maintain.

The powerful diesel-electric Zephyr arrived in 1934; its technology was a result of the Navy’s search for an improved submarine engine.

Overton, author of Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines, noted the burning fuels ranged from a low-grade gasoline to painter’s naphtha and diesel.

The distillate railroad engines emitted an oily smoke and often produced only a single horsepower from 80 pounds of engine weight. The common four-stroke engines fouled easily and required multiple spark plugs per cylinder.

Help for America’s failing passenger railroads would come from U.S. Navy diesel-electric engine technology, wrapped in a stainless steel Art Deco locomotive.

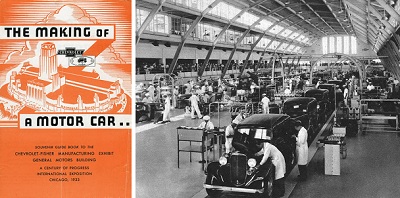

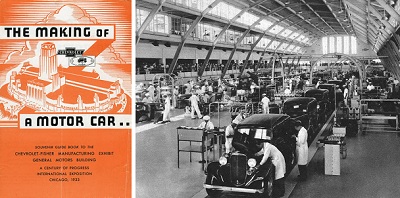

New diesel-electric engines generated power for the “Making of a Motor Car” exhibit at the 1933 Century of Progress fair in Chicago. The assembly line fascinated visitors who watched from overhead galleries.

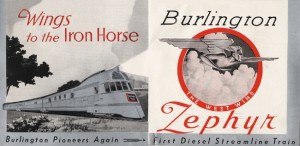

“Wings to the Iron Horse…Burlington pioneers again — the first diesel streamline train,” proclaimed passenger rail advertisements in the 1930s. The long-awaited technology for railroad diesel-electric engines had arrived.

Diesel-Electric Hybrid

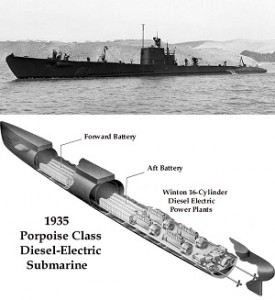

With the Nazi threat and war on the horizon, the U.S. Navy needed a lighter-weight, more powerful diesel engine for its submarines. The Navy also recognized it had been too slow in converting its surface vessels from coal to fuel oil (see Petroleum and Sea Power). General Motors joined the nationwide competition to develop a new diesel engine for the Navy.

Seeking engineering and production expertise, in 1930 GM acquired the Winton Engine Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Winton, established in 1896 as Winton Bicycle Company, was an early automobile manufacturer. Winton Engine Company evolved into a developer of engines for marine applications, power companies, pipeline operators — and railroads.

America’s first diesel-electric train, the Burlington Zephyr, was a transportation milestone.

With GM’s financial backing, Winton engineers designed a radical new two-stroke diesel that delivered one horsepower per 20 pounds of engine weight. It provided a four-fold power to weight gain.

The Model 201A prototype — a 503-cubic-inch, 600 horsepower, 8-cylinder diesel-electric engine — used no spark plugs, relying instead on newly patented high-pressure fuel injectors and a 16:1 compression ratio for ignition.

Powered by an eight-cylinder Winton 201A diesel engine, the revolutionary streamliner traveled the 1,015 miles from Denver to Chicago in just over 13 hours — a passenger train record.

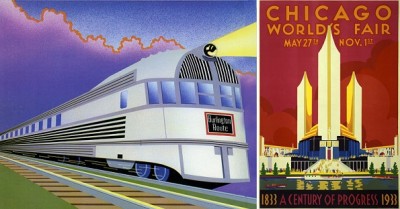

At Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933, GM evaluated two railroad diesel-electric engines, using them to generate power for its “Making of a Motor Car” exhibit. The working demonstration of a Chevrolet assembly line fascinated thousands of visitors who watched from overhead galleries.

The Burlington Line

One visitor happened to be Ralph Budd, president of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (known as the Burlington Line). Budd recognized the locomotive potential of these extraordinary new diesel-electric power plants. He saw them as a perfect match for the lightweight “shot-welded” stainless steel rail cars pioneered by the Edward G. Budd (no relation) Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia.

During its “dawn to dusk” record-breaking run, the Zephyr burned only $16.72 worth of diesel fuel.

Edward Budd pioneered supplying all-steel bodies to the automobile industry in 1912. His success in steel stamping technology made the production of them cheaper and faster. By 1925, his system was used to produce half of all U.S. auto bodies.

However, the Depression put the Budd Manufacturing Company almost $2,000,000 in the red — prompting its fortuitous diversification into the railroad car market to generate revenue. When approached by Burlington President Ralph Budd in 1933, this Budd was ready.

Chicago World’s Fair visitors line up to admire the stainless steel beauty of the Burlington Zephyr, which will soon be featured in a Hollywood movie. Eight major U.S. railroads soon convert to efficient diesel-electric locomotives. Photo from a Burlington Route Railroad 1934 postcard.

Within a year, the two technologies were successfully merged with the creation of the Winton 201A-powered Burlington Zephyr, America’s first diesel-electric train. It would change railroad transportation history.

Submarine Engines

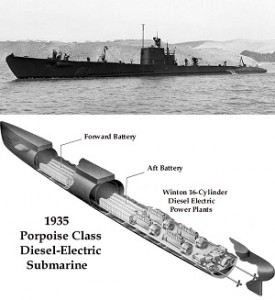

General Motors in 1932 won the Navy’s competition for a lightweight and powerful diesel-electric. The Navy decided a 16-cylinder Winton would power a new class of submarines.

Winton diesel-electric engines powered a new generation of U.S. submarines. The first of its class, Porpoise (SS-172), joined the fleet in 1935 and served throughout World War II.

In 1935, the USS Porpoise became the first to join the fleet, and it served throughout World War II. All of the silent-service’s diesel-electrics power plants descended from the Burlington Zephyr. They would remain part of the fleet until replaced by nuclear propulsion.

The Speedy Zephyr

When the Zephyr rolled into Chicago’s Century of Progress exhibition on May 26, 1934, it ended a nonstop 13-hour, 4-minute, and 58-second “dawn to dusk” promotional run from Denver. Powered by a single eight-cylinder Winton 201A diesel, the streamliner cut average steam locomotive time by half.

The Zephyr had traveled 1,015 miles at an average speed of 76.61 miles per hour, It often sped along the route in excess of 112 mph — amazing lines of trackside spectators. Crowds of Zephyr-watchers could be found from Colorado to Illinois.

During its record-breaking run, the Zephyr burned just $16.72 worth of diesel fuel (about four cents per gallon). The same distance in a coal steamer would have cost $255. Construction innovations included the specialized shot-welding that joined sheets of stainless steel.

Further, the lightweight steel resisted corrosion so it didn’t have to be painted.

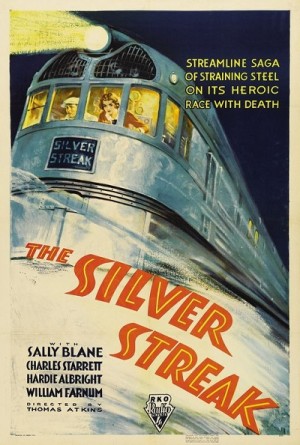

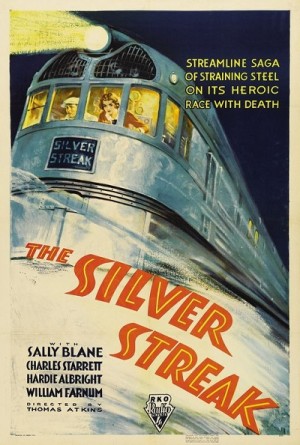

Considered a 1934 “B” movie — intended for the bottom half of double features — ”The Silver Streak” would remain a favorite of many railroad history fans.

Americans fell in love with the Zephyr. Four months after its high-speed appearance at Chicago’s Century of Progress, the streamliner made its 1934 Hollywood film debut, starring as “The Silver Streak” for an RKO picture.

Burlington loaned its Zephyr for the movie’s filming. Repainted, the company logo on the front became the Silver Streak. “The streamlined train, platinum blonde descendant of the rugged old Iron Horse, has been glorified by Hollywood in the modern melodrama,” proclaimed the New York Times.

Surprisingly, the black-and-white “B” movie came and went without drawing many theatergoers. But it has since won its place in movie history as a rail-fan favorite, according to a 2001 article in the Zephyr Online. “It did have a lot of action, and the location shots of the Zephyr are an interesting record of this pioneer.”

The RKO film should not be confused with 20th Century Fox’s 1976 comedy “Silver Streak” filmed in Canada using Canadian Pacific Railway equipment from the Canadian, a transcontinental passenger train.

End of Steam

Meanwhile, by the end of 1934, eight major U.S. railroads had ordered diesel-electric locomotives. The engine technology’s cost advantages in manpower, maintenance, and support were quickly apparent.

Despite the greater initial cost of diesel-electric, a century of steam locomotive dominance soon came to an end. By the mid-1950s, steam locomotives were no longer being manufactured in the United States.

A Zephyr competitor, the Union Pacific M-10000 built by the Pullman Car & Manufacturing Company, also showcased railroad diesel-electric engine technology at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago.

In fact, the aluminum M-10000 streamliner was revealed six weeks earlier than the Zephyr. Recognized as America’s first streamliner, the M-10000 was cut up for scrap in 1942. The Zephyr (later renamed the Pioneer Zephyr) ended up on display at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines (1965); Burlington’s Zephyrs, Great Passenger Trains (2004); The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America

(2004); The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America (2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Adding Wings to the Iron Horse.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/adding-wings-to-the-iron-horse. Last Updated: May 21, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | May 15, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

Famous 1880s New York World reporter took charge of Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

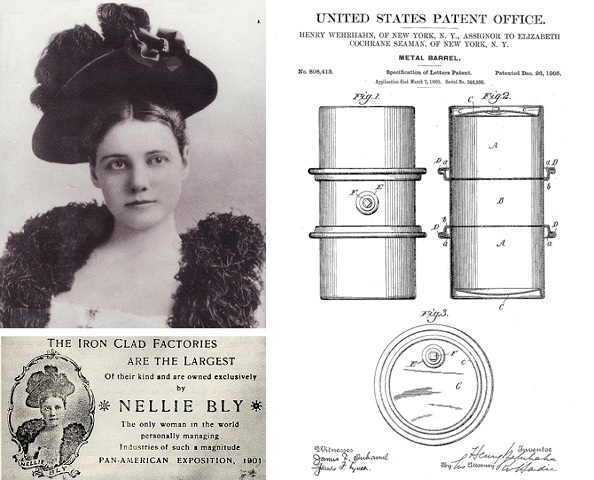

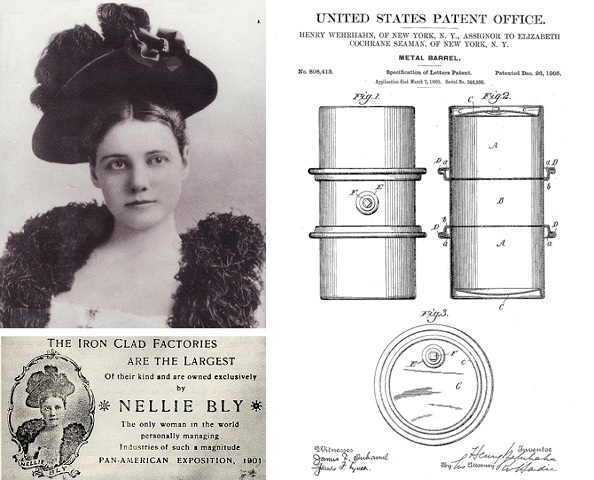

She was one of the most famous journalists of her day as a reporter for the New York World. Widely known as the remarkable Nellie Bly, Elizabeth J. Cochran Seaman, investigated conditions at an infamous mental institution, made a trip around the world in less than 80 days — and manufactured the first practical 55-gallon oil drum.

The 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y., promoted her Iron Clad Manufacturing Company as “owned exclusively by Nellie Bly – the only woman in the world personally managing industries of such magnitude.”

Recognizing the potential of an efficient metal barrel design, Nellie Bly acquired the 1905 patent rights from its inventor, Henry Wehrhahn, who worked at her Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Apr 4, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

Densmore brothers advanced oil industry infrastructure — and helped create “QWERTY” typewriter keyboard.

As Northwestern Pennsylvania oil production skyrocketed following the Civil War, railroad oil tank cars fabricated by two brothers improved shipment volumes from oilfields to kerosene refineries. The tank car designed by James and Amos Densmore would not last, but more success followed when Amos invented a new keyboard arrangement for typewriters.

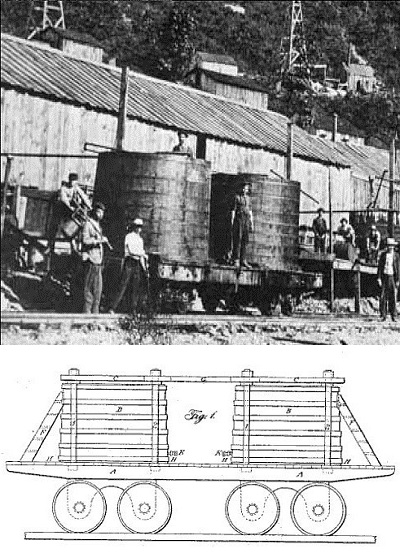

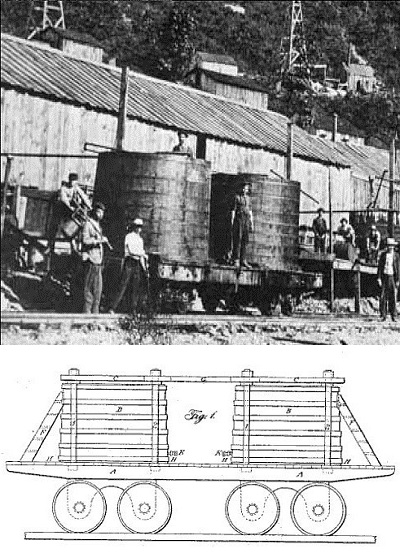

Flatbed railroad cars with two wooden oil tank cars became the latest advancement in oilfield infrastructure after the Densmore brothers patented their design on April 10, 1866.

The inventors from Meadville, Pennsylvania, had developed an “Improved Car for Transporting Petroleum” one year earlier in America’s booming oil regions. The first U.S. oil well had been drilled just seven years earlier along Oil Creek in Titusville.

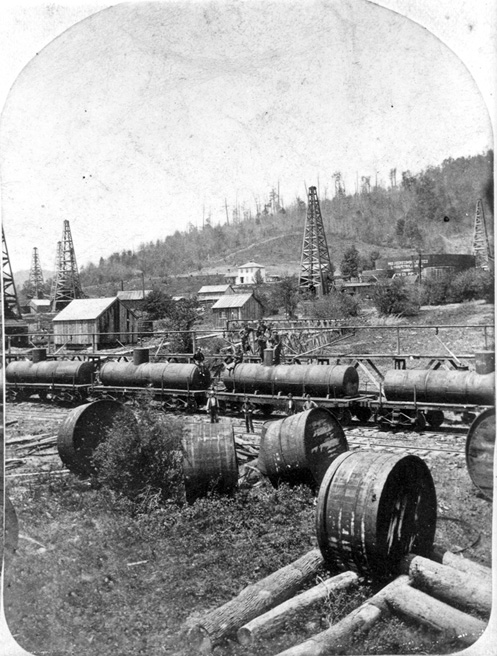

The first practical petroleum railway tank car was invented in 1865 by James and Amos Densmore at the Miller Farm along Oil Creek, Titusville, Pennsylvania. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

Using an Atlantic & Great Western Railroad flatcar, the brothers secured two tanks to ship oil in bulk. The patent (no. 53,794) described and illustrated the railroad car’s design.

The nature of our invention consists in combining two large, light tanks of iron or wood or other material with the platform of a common railway flat freight-car, making them practically part of the car, so as they carry the desired substance in bulk instead of in barrels, casks, or other vessels or packages, as is now universally done on railway cars.

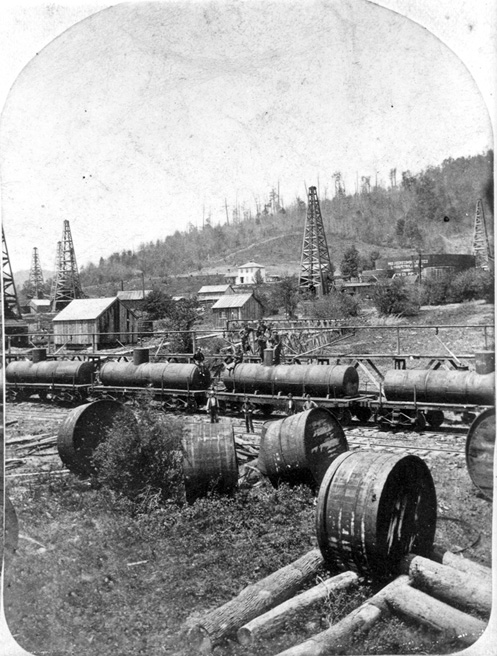

Development of railroad tank cars came when traditional designs, including the flatcar, hopper, and boxcar, proved inadequate for large amounts of oil — often shipped in 42-gallon barrels.

New designs were born out of necessity, as the fledgling oil industry demanded a better car for the movement of its product, according to American-Rails.com.

“Before the car was developed, railroads used a combination of boxcars, flatcars, and gondolas to haul everything from lumber and coal to crude oil, molasses, and water (by use of barrels),” noted Adam Burns in 2022. “One of the most prolific car types you will find moving within a freight train today is the tank car.”

Prone to leaks and top heavy, Densmore tank cars provided a vital service, if only for a few years before single, horizontal tanks replaced them.

According to transportation historian John White Jr., the Densmore brothers’ oil tank design essentially consisted of a flat car with wooden vats attached. “The Central Pacific is known to have used such specialized cars to transport water, he noted in his 1995 book, The American Railroad Freight Car.

“However, prior to the discovery of oil by Colonel Edward (sic) Drake near Titusville, Pennsylvania, on August 27, 1859, the tank car was virtually non-existent,” added White, a former curator of Transportation at the Smithsonian Institution.

Dual Tank Design

The brothers further described the use of special bolts at the top and bottom of their tanks to act as braces and “to prevent any shock or jar to the tank from the swaying of the car while in motion.”

A Pennsylvania Historical Commission marker on U.S. 8 south of Titusville commemorates the Densmore brothers’ significant contribution to petroleum transportation technology. Dedicated in 2004, the marker notes:

The first functional railway oil tank car was invented and constructed in 1865 by James and Amos Densmore at nearby Miller Farm along Oil Creek. It consisted of two wooden tanks placed on a flat railway car; each tank held 40-45 barrels of oil. A successful test shipment was sent in September 1865 to New York City. By 1866, hundreds of tank cars were in use. The Densmore Tank Car revolutionized the bulk transportation of crude oil to market.

The benefit of such railroad cars to the early petroleum industry’s infrastructure was immense, especially as more Americans eagerly sought oil-refined kerosene for lamps.

Despite design limitations that would prove difficult to overcome, independent producers took advantage of the opportunity to transport large amounts of petroleum. Other transportation methods required teamsters hauling barrels to barges on Oil Creek and the Allegheny River to get to kerosene refineries in Pittsburgh.

Riveted cylindrical iron tank cars replaced the Densmore brothers’ dual wooden tanks — seen here discarded. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

As larger refineries were constructed, it was found that it cost $170 less to ship 80 barrels of oil from Titusville to New York in a tank car instead of individual barrels. But the Densmore cars had flaws, notes the Pennsylvania Historical Commission.

They were unstable, top heavy, prone to leaks, and limited in capacity by the eight-foot width of the flatcar. Within a year, oil haulers shifted from the Densmore vertical vats to larger, horizontal riveted iron cylindrical tanks, which also demonstrated greater structural integrity during derailments or collisions.

The same basic cylindrical design for transporting petroleum can be seen as modern railroads load products from corn syrup to chemicals — all in a versatile tank car that got its start in the Pennsylvania oil industry.

The largest tank car ever placed into regular service was Union Tank Car Company’s UTLX 83699, rated at 50,000 gallons in 1963 and used for more than 20 years. A 1965 experimental car built by General American Transportation, the 60,000-gallon “Whale Belly,” GATX 96500, is now on display at the National Museum of Transportation in Saint Louis.

1863 Tank Car Patents

Although not manufactured, other inventors came up with new ways for transporting oil from booming oilfields. John Scott of Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, on January 20, 1863, patented (No. 37,461) a rectangular design for his “car for carrying petroleum, etc.”

John Clark of Canandaigua, New York, on November 3, 1863, was awarded a patent (No. 40,458) for another “improvement in cars for carrying petroleum.” His design put a long and flat sheet-metal tank under an ordinary freight car.

Finally, a “Petroleum Car” design with a cylindrical shape similar to modern railroad tank cars was patented (No. 38,765) on June 2, 1863, by Samuel J. Seely of Bookland, New York. The Seely patent might be the first design for a petroleum car shaped like those in use today.

Oil Tanks to Typewriters

Although the Densmore brothers left the oil region by 1867 — their inventiveness was far from over. In 1875, Amos Densmore assisted Christopher Sholes in rearranging the “type writing machine” keyboard so that commonly used letters no longer collided and got stuck. The “QWERTY” arrangement vastly improved Shole’s original 1868 invention.

Amos Densmore helped invent one of the first practical typewriters.

Following his brother’s work with Sholes, inventor of the first practical typewriter, James Densmore’s oilfield financial success helped the brothers establish the Densmore Typewriter Company, which produced its first model in 1891. Few historians have made the oil patch to typewriter keyboard connection — including Densmore biographers.

The Pennsylvania Historical Commission reported that biographies of the Densmore brothers — and their personal papers at the Milwaukee Public Museum — all refer to their innovative typewriters, “but make no mention of their pioneering accomplishment in railroad tank car design.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Early Days of Oil: A Pictorial History of the Beginnings of the Industry in Pennsylvania (2000); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2000); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Densmore Oil Tank Cars.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/densmore-oil-tank-car. Last Updated: July 14, 2025. Original Published Date: April 7, 2013.