by Bruce Wells | Feb 12, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Reports of a “mineral tar” from the 1840s helped H.L. Hunt discover an oilfield a century later.

Swallowing “tar pills” supposedly had been curing ills since the mid-1800s, but Alabama’s petroleum industry officially began in 1944 with a Choctaw County well drilled by a well-known Texas wildcatter. On February 17, independent producer Haroldson Lafayette “H.L” Hunt completed his Jackson No. 1 well after discovering Alabama’s first oilfield.

H.L. Hunt had found success in the earliest Arkansas oilfields of the 1920s and even greater success in the East Texas oilfield of the 1930s. He now had revealed the Gilbertown oilfield of western Alabama, about 50 miles southeast of Meridian, Mississippi.

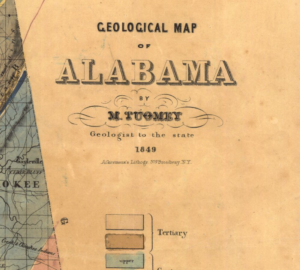

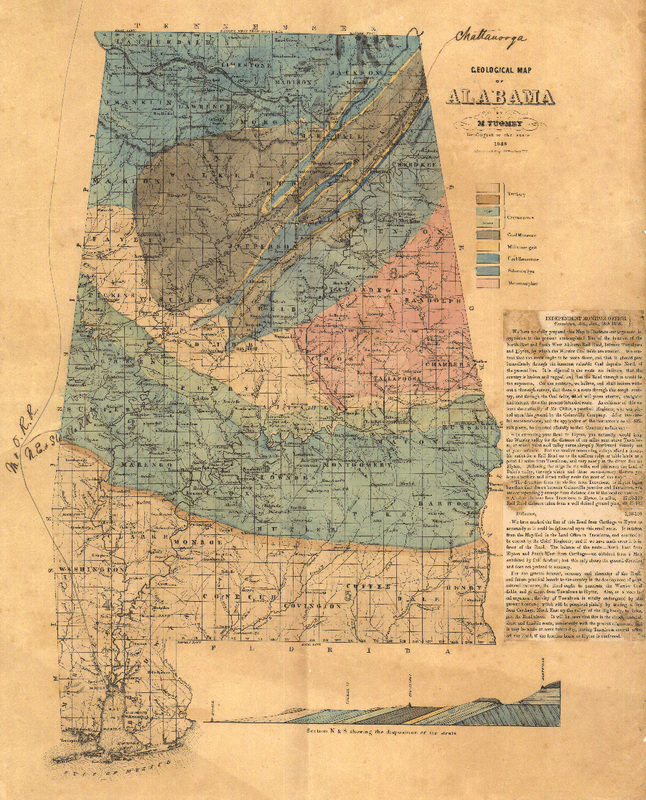

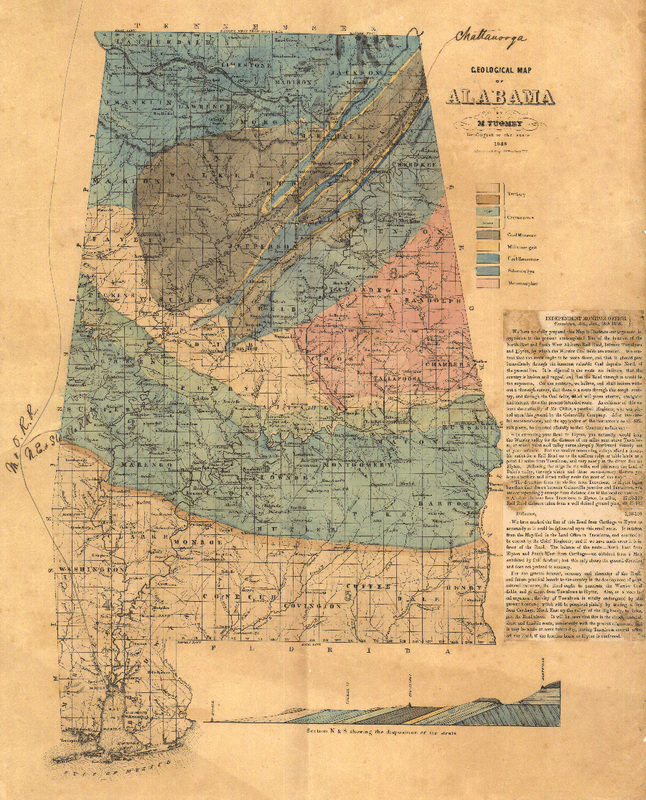

Geological Map of Alabama, printed in 1849 by Michael Tuomey, professor of geology, mineralogy and agricultural chemistry at the University of Alabama. Tuomey published his First Biennial Report of the Geology of Alabama in 1850. Map courtesy University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections.

Despite limited knowledge of the state’s geology, regions with oil and natural gas seeps had attracted interest as early as the mid-19th century. Before Hunt’s Choctaw County wildcat well, 350 dry holes had been drilled in Alabama.

Geologist and petroleum historian Ray Sorenson has investigated the earliest reports of petroleum in all producing states. By the early 2020s, his ongoing project documented the first signs of oil in the United States, Canada, and many parts of the world (see Exploring Earliest Signs of Oil).

In Alabama’s case, Sorenson uncovered an account by an early expert in the scientific field of geology. The first Alabama state geologist, Michael Tuomey, described reports of a “mineral tar,” and cited an 1840s account of finding natural oil seeps six miles from Oakville in Lawrence County.

With quantities of oil and water emerging from a crevice in limestone, Tuomey observed that “the tar, or bitumen, floats on the surface, a black film very cohesive and insoluble in water.”

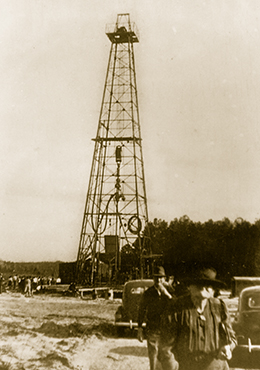

The A.R. Jackson No. 1 well in 1944 revealed an Alabama oilfield near the Mississippi border. Photo courtesy Hunt Oil Company.

Similar to “Kentucky oil,” Alabama’s Lawrence County oil became popular for its medicinal qualities. Oil from the county was claimed to be “a known cure for Scrofula, Cancerous Sores, Rheumatism, Dyspepsia,” and other diseases.

“Patients visiting the Spring find the tar taken and swallowed as pills, the most efficient form of the remedy,” Tuomey quoted the observation from “Tar Spring of Lawrence” in the 1858 Second Biennial Report On the Geology of Alabama (published one year after his death).

Tuomey served as the state geologist of South Carolina from 1844 to 1847, and as the first state geologist of Alabama from 1848 until his death in 1857. His Geological Map of Alabama was printed in 1849.

In addition to oil, traces of natural gas were discovered in Alabama in the late 1880s, and by 1902, natural gas was being supplied to Huntsville and the town of Hazel Green, according to Alabama historian Alan Cockrell.

“In 1909, a small discovery by Eureka Oil and Gas at Fayette fueled that city’s streetlights for a time, but no natural gas was recovered anywhere in the state for several decades afterward,” he added. Learn about the earliest oilfield discoveries in other producing states in First Oil Discoveries.

Gilbertown Oil Discovery

According to Cockrell, Alabama’s oil and natural gas industry did not truly begin until H.L. Hunt of Dallas, Texas, drilled in Choctaw County near the Mississippi border and discovered the Gilbertown oilfield.

Concrete foundations are all that remains of Alabama’s first oil well, the A.R. Jackson Well No. 1, completed in 1944 near Gilbertown. Photo courtesy Explore Rural S.W. Alabama.

After five weeks of drilling, the well was completed on February 17, 1944, at 2,585 feet in the Selma chalk of the Upper Cretaceous. Hunt’s A.R. Jackson Well No. 1 two miles southwest of downtown Gilbertown had reached a total depth of 5,380 feet before being “plugged back” to its most productive oil-producing geologic formation.

H.L. Hunt’s first Alabama oil well produced just 30 barrels of oil a day, but launched the state’s petroleum industry. “The discovery of this well led to the creation of the State Oil and Gas Board of Alabama in 1945, and to the development and growth of the petroleum industry in Alabama,” notes an Alabama historic marker erected at the site.

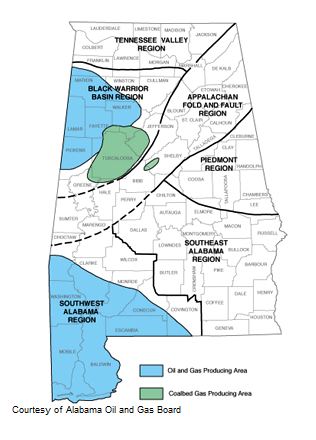

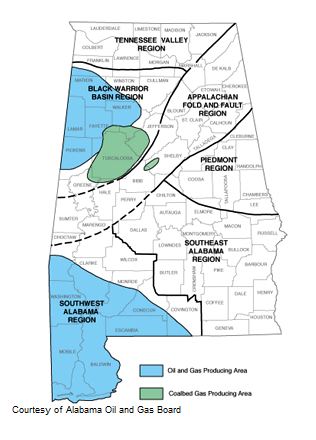

Deeper drilling led to more Alabama petroleum discoveries in the 1980s. Map courtesy Encyclopedia of Alabama.

The first oilfield would produce 15 million barrels of oil, “not a lot by modern standards but enough to make ‘oil fever’ spread rapidly,” Cockrell noted in “Oil and Gas Industry in Alabama” in 2008. The search for another oilfield took 11 more years.

The 1955 oil discovery at Citronelle, a town above a geologic salt dome, finally launched a new drilling boom; five new Alabama oilfields were discovered by 1967. Mobil Oil Company drilled Alabama’s first successful offshore natural gas well in 1981.

As production technologies advance, geologists believe opportunities exist in the “hard shales of the deep Black Warrior Basin beneath Pickens and Tuscaloosa counties and in the thick fractured shales of St. Clair and neighboring counties,” according to Cockrell.

By 2022, more than 17,500 oil and natural gas wells had been drilled in Alabama since the state’s first commercial oil discovery in 1944. According to the Washington, DC-based Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA), about 10 percent of the Alabama wells produced oil, 59 percent natural gas, and 30 percent (about 5,000 wells) were nonproductive.

Mapping Mineral Riches

From the journal Cartographic Perspectives of the North American Cartographic Information Society (NACIS):

Settlement of the newly available land enabled Alabama to move rapidly from being a part of the Mississippi Territory to its own Alabama Territory, and finally to statehood in 1819. The favorable climate and rich soil brought large plantations and slavery.

Appointed State Geologist of Alabama in 1848, Michael Tuomey served until his death in 1857.

Michael Tuomey (1805-1857), professor of geology at the University of Alabama in the 1840s, had attempted to lead Alabama’s economy away from slavery-based agriculture. In 1849, he produced the first survey of the state’s mineral wealth. His map Geological map of Alabama showed exactly where the state’s natural riches were located. The efforts of Tuomey and others were rejected, as were similar efforts in other southern states.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide (2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

(2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Alabama Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-alabama-oil-well. Last Updated: February 12, 2025. Original Published Date: October 21, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 17, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

When a Fort Worth independent producer completed a remote wildcat well in East Texas on January 26,1931, the well revealed the true extent of an oilfield discovered months earlier and many miles away.

As the Great Depression worsened and East Texas farmers struggled to survive, W.A. “Monty” Moncrief and two partners drilled the Lathrop No. 1 well in Gregg County. When completed in 1931, their well produced 320 barrels of oil per hour from a depth of 3,587 feet.

Far from what earlier were thought to be two oilfield discoveries — this third well producing 7,680 barrels a day revealed a “Black Giant.”

A circa 1960 photograph of W.A. “Monty” Moncrief and his son “Tex” in Fort Worth’s Moncrief Building.

Moncrief, who had worked for Marland Oil Company in Fort Worth after returning from World War I, drilled in an region (and a depth) where few geologists thought petroleum production a possibility. He and fellow independent operators John Ferrell and Eddie Showers thought otherwise.

The third East Texas well was completed 25 miles north of Rusk County’s already famous October 1930 Daisy Bradford No. 3 well drilled by Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner northwest of Henderson (and southeast New London, site of a tragic 1937 school explosion).

Moncrief’s oil discovery came 15 miles north of the Lou Della Crim No. 1 well, drilled three days after Christmas, on “Mama” Crim’s farm about nine miles from the Joiner well. At first, the distances between these “wildcat” discoveries convinced geologists, petroleum engineers (and experts at the large oil companies) the wells were small, separate oilfields. They were wrong.

Three Wells, One Giant Oilfield

To the delight of other independent producers and many small, struggling farmers, Moncrief’s Lathrop discovery showed that the three wells were part of a single petroleum-producing field. Further development and a forest of steel derricks revealed the northernmost extension of the 130,000-acre East Texas oilfield.

The history of the petroleum industry’s gigantic oilfield has been preserved at the East Texas Oil Museum, which opened at Kilgore College in 1980. Joe White, the museum’s founding director, created exhibit spaces for the “authentic recreation of the oil discoveries and production in the early 1930s in the largest oilfield inside U.S. boundaries.”

After more than half a century of major discoveries, William Alvin “Monty” Moncrief died in 1986. His legacy has extended beyond his good fortune in East Texas.

The family exploration business established by Moncrief in 1929 would be led by sons W.A. “Tex” Moncrief Jr. and C.B. “Charlie” Moncrief, who grew up in the exploration business. In 2010, Forbes reported that 94-year-old “Tex” made “perhaps the biggest find of his life” by discovering an offshore field of about six trillion cubic feet of gas.

Moncrief Philanthropy

Hospitals in communities near the senior Moncrief’s nationwide discoveries, including a giant oilfield in Jay, Florida, revealed in 1970, and another in Louisiana, have benefited from his drilling acumen.

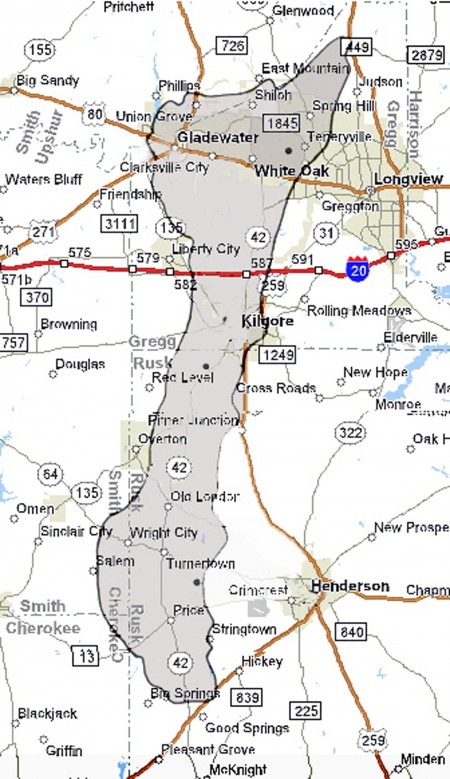

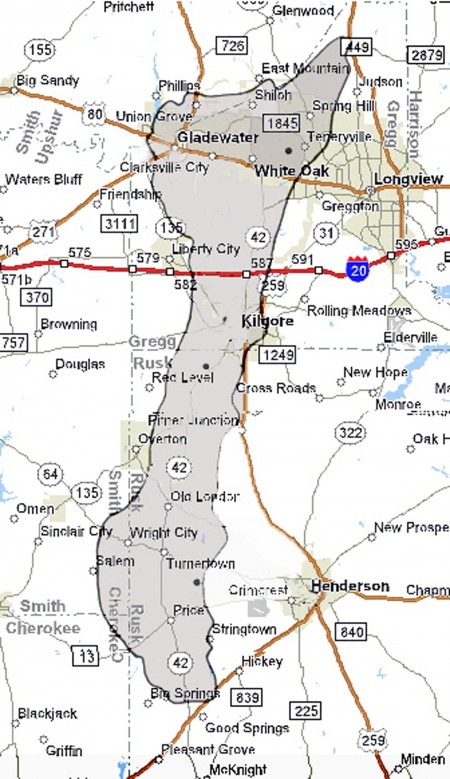

The 130,000-acre East Texas oilfield became the largest in the contiguous United States in 1930.

Moncrief and his wife established the William A. and Elizabeth B. Moncrief Foundation and the Moncrief Radiation Center in Fort Worth, as well as the Moncrief Annex of the All Saints Hospital. Buildings in their honor have been erected at Texas Christian University, All Saints School, and Fort Worth Country Day School.

Dr. Daniel Podolsky in 2013 presented W.A. “Tex” Moncrief Jr. with a framed image of the new Moncrief Cancer Institute at the Fort Worth facility’s dedication ceremony.

Supported throughout the 1960s and 1970s by the Moncrief family, Fort Worth’s original Cancer Center, known as the Radiation Center, was founded in 1958 as one of the nation’s first community radiation facilities.

In 2013, the $22 million Moncrief Cancer Institute was dedicated during a ceremony attended by “Tex” Moncrief Jr. “One man’s vision for a place that would make life better for cancer survivors is now a reality in Fort Worth,” noted one reporter at the dedication of the 3.4-acre facility at 400 W. Magnolia Avenue.

Small investments from hopeful Texas farmers will bring historic results — and make Kilgore, Longview and Tyler boom towns during the Great Depression. Kilgore today celebrates its petroleum heritage.

Early Days in Oklahoma

Born in Sulphur Springs, Texas, on August 25, 1895, Moncrief grew up in Checotah, Oklahoma, where his family moved when he was five. Checotah was the town where Moncrief attended high school, taking typing and shorthand — and excelling to the point that he became a court reporter in Eufaula, Oklahoma.

To get an education, Moncrief saved $150 to enroll at the University of Oklahoma at Norman, where he worked in the registrar’s office. He became “Monty” after his initiation into the Sigma Chi fraternity.

During World War I, Moncrief volunteered and joined the U.S. Cavalry. He was sent to officer training camp in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he met, and six months later married, Mary Elizabeth Bright on May 28, 1918. Sent to France, Moncrief saw no combat thanks to the Armistice being signed before his battalion reached the front.

After the war, Moncrief returned to Oklahoma where he found work at Marland Oil, first in its accounting department and later in its land office. When Marland opened offices in Fort Worth in the late 1920s, Moncrief was promoted to vice president for the new division.

In 1929, Moncrief would strike out on his own as an independent operator. He teamed up with John Ferrell and Eddie Showers, and they bought leases where they ultimately drilled the successful F.K. Lathrop No. 1 well.

C.M. “Dad” Joiner’s partner, the 300-pound self-taught geologist A.D. “Doc” Lloyd, had predicted the field would be four to ten miles wide and 50 to 50 miles long, according to Moncrief, interviewed in 1985 for Wildcatter: A Story of Texas Oil.

“Of course, everyone at the time thought he was nuts, including me,” the Texas wildcatter added. Also interviewed, museum founder Joe White said Lloyd’s assessment predicted the Woodbine sands at a depth of 3,550 — about two thousand of feet shallower than major oil company geologists believed.

Moncrief’s Lathrop January 1931 wildcat well, which produced from the Woodbine formation at a depth of 3,587 feet, proved the oilfield stretched 42 miles long and up to eight miles wide — the largest in the lower-48 states.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skulduggery & Trivia (2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Moncrief makes East Texas History.” Authors: B.A. and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/moncrief-oil. Last Updated: January 17, 2025. Original Published Date: January 25, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 3, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

New England history lesson in a failed 2019 petition effort.

Community activists in Connecticut tried but could not preserve a Standard Oil barn. Town officials approved a plan to establish a new plaza at Mead Park on the former site of the “Brick Barn” in October 2019.

The demolished structure was once a Standard Oil Company of New York storage and distribution facility built around 1910 and eventually in a city park. “Save Mead Park Brick Barn” organizers learned a lot of petroleum history in their failed preservation cause.

They were trying to save among the last circa 1900 horse-drawn oil delivery facility in Connecticut, according to Andrea Sandor in a January 30, 2018, email to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Sandor attached documents about a Standard Oil Company facility in New Canaan at Mead Park.

Demolished in 2019, this was the 1901 Standard Oil Company facility for horse-drawn wagons that distributed Connecticut kerosene.

Among the petitioners for the building’s preservation was Robin Beckett, a New Canaan resident of more than two decades, who proclaimed the town held a “unique sense of place and character among the other towns in Fairfield County and the State of Connecticut.”

For years Beckett has advocated preserving the Standard Oil structure, a brick barn built by the company around 1910 — “a time when the company shipped kerosene from its refineries by rail car to bulk stations from where horse-drawn tank wagons distributed it to local hardware stores thence sold to the consumer,” she explained.

Beckett discovered many little-known details about the barn during her research to prevent its being demolished: The selection of New Canaan in 1901 as a site for Standard Oil’s kerosene and gasoline facilities made available to residents (about 2,000 at the time), “the opportunity to have a new fuel source and to have life-style altering modern age products.”

The 800-square-foot building is similar in design to a 19th-century carriage house. Twenty-four acres of the Mead family land surrounding the Standard Oil property was sold to the town for one dollar in 1915 by the widow of Benjamin P. Mead, upon his death. It became a park in 1930.

During World War II, volunteer women sewed clothes for refugees and folded bandages there; the American Legion held meetings there after the war; the VFW Fife and Drum Corps and the Town Band practiced at the site; and the New Canaan Garden Center planted a Gold Star Walk memorializing war casualties.

“There is no other structure like The Barn in New Canaan,” Beckett maintained. It also could be the last remaining structure of its type and style in the state. She has located a 1927 Standard Oil Company of New York map of the barn’s site on Richmond Hill Road. “The complex of six buildings that Standard Oil constructed in New Canaan in 1901 could be considered a precursor or early version of the now ubiquitous filling station thus yielding another piece of information about history.”

The Barn is the last of the original six, “and now the structure, its cultural history — both local and in the context of the national history are understood,” proclaims Beckett. It was almost demolished in 2009 until a delay was granted by the Historic Review Committee. It has been used as a city garage most of the time since.

“I feel the town has a responsibility to listen to the nearly 500 petitioners who recognize The Barn’s historical significance and support it productive, adaptive reuse,” she concluded. Beckett also believes the building should be placed on the State Register of Historic Places. The Friends of the Mead Park Carriage Barn launched their petition drive in 2010, according to the New Canaan Patch.

“We’re talking to different organizations and researching public and private funding for the renovation. Whatever its future use would be, if preserved and restored it would remain a piece of New Canaan’s history and past and that’s worth saving,” noted activist Mimi Findlay. The small community has been home to several leading petroleum industry executives (learn more in Oil Executives in Connecticut).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The History of the Standard Oil Company: All Volumes  (2015); Oil Lamps, The Kerosene Era In North America

(2015); Oil Lamps, The Kerosene Era In North America (1978). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1978). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Preserving a Standard Oil Barn.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/standard-oil-barn-connecticut. Last Updated: January 12, 2025. Original Published Date: September 6, 2019.

(2000). Drilling Ahead, The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005 (2005). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.