by Bruce Wells | Dec 19, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Oil discovery on widow’s East Texas farm confirmed the size of largest oilfield in the lower 48 states.

Some people claimed a gypsy told Malcolm Crim he would discover oil in East Texas three days after Christmas. Others said it was because his mother, Lou Della “Mama” Crim, was a pious woman.

On December 28, 1930, the exploratory well Lou Della Crim No. 1 began producing an astonishing 20,000 barrels of oil a day. Even then, few appreciated the true significance of the Rusk County well drilled by Mrs. Crim’s eldest son, Malcolm. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 3, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

New Mexico wildcatter discovers high-grade uranium after decades of drilling dry holes.

Stella Dysart spent almost 30 years unsuccessfully searching for oil in New Mexico. In 1955, a radioactive uranium sample from one of her “dusters” made her a very wealthy woman.

In the end, it was the uranium — not petroleum — that made Dysart her fortune. The sometimes desperate promoter of oil drilling ventures in New Mexico for more than 30 years, she once served time for fraud. But in 1955, Mrs. Dysart learned she owned the world’s richest deposit of high-grade uranium ore.

LIFE magazine featured Stella Dysart in 1955 after she made a fortune from finding uranium but failed in her oil ventures.

Born in 1878 in Slater, Missouri, Dysart moved to New Mexico, where she got into the petroleum and real estate business in 1923. She ultimately acquired a reported 150,000 acres in the remote Ambrosia Lake area 100 miles west of Albuquerque, on the southern edge of the oil-rich San Juan Basin.

Dysart established the New Mexico Oil Properties Association and the Dysart Oil Company. The ventures and other investment schemes would leave her broke, according to John Masters and Paul Grescoe in their 2002 book, Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman.

The authors describe Dysart as a woman who drilled dry holes, peddled worthless parcels of land to thousands of dirt-poor investors, and went to jail for one of her crooked deals.

Dysart subdivided her properties and subdivided again — selling one-eighth acre leases and oil royalties as small as one-six thousandth to investors. She drilled nothing but dry holes for years. Then it got worse.

Before finding uranium, Stella Dysart served 15 months for the unauthorized selling of New Mexico oil leases. In 1941, she promoted her Dysart No. 1 Federal well, above, which was never completed.

A 1937 Workmen’s Compensation Act judgment against Dysart’s New Mexico Oil Properties Association bankrupted the company, compelling sale of its equipment, “sold as it now lies on the ground near Ambrosia Lake.”

Two years later, it got worse again. Dysart and five Dysart Oil Company co-defendants were charged with 60 counts of conspiracy, grand theft, and violation of the Corporate Securities Act in 1939. All were convicted, and all did time. Dysart served 15 months in the county jail before being released on probation in March 1941.

Uranium Riches

By 1952, 74-year-old Dysart was $25,000 in debt when she met uranium prospector Louis Lothman, a young Texan just two years out of college with a geology degree.

When Lothman examined cuttings from a Dysart dry hole in McKinley County in 1955, he got impressive Geiger counter readings. The drilling of several more test wells confirmed the results. Dysart owned the world’s richest deposit of high-grade uranium ore.

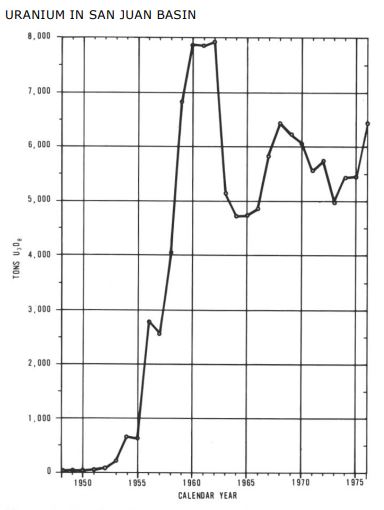

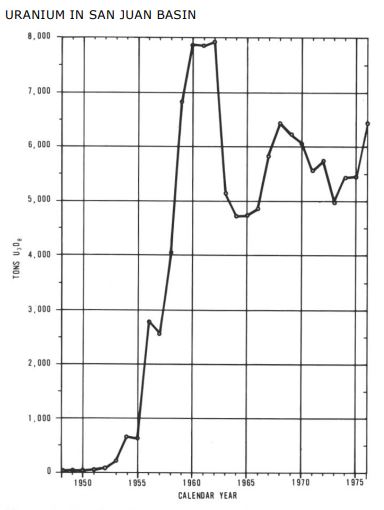

Uranium production in the San Juan Basin, 1948-1975 courtesy New Mexico Geological Survey.

The uranium discovery launched an intensive exploration effort that led to the development of multi-million-ton deposits in the Ambrosia Lake area, according to William L. Chenoweth of the U.S. Energy Research and Development Administration.

“The San Juan Basin of northwest New Mexico has been the source of more uranium production than any other area in the United States,” he noted in a New Mexico Geological Survey 1977 report, “Uranium in the San Juan Basin.”

Dysart was 78 years old when the December 10, 1955, LIFE magazine featured her picture, captioned: “Wealthy landowner, Mrs. Stella Dysart, stands before abandoned oil rig which she set up on her property in a long vain search for oil. Now uranium is being mined there and Mrs. Dysart, swathed in mink, gets a plump royalty.”

Praised for her success, and memories of fraudulent petroleum deals long forgotten, Dysart died in 1966 in Albuquerque at age 88. As Secret Riches author John Masters explained, “there must be a little more to her story, but as someone said of Truth — ‘it lies hidden in a crooked well.’”

More New Mexico petroleum history can be found in Farmington, including the exhibit “From Dinosaurs to Drill Bits” at the Farmington Museum. Learn about the giant Hobbs oilfield of the late 1920s in New Mexico Oil Discovery.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Stella Dysart of Ambrosia Lake: Courage, Fortitude and Uranium in New Mexico (1959); Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman (2004). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1959); Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman (2004). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: Legend of “Mrs. Dysart’s Uranium Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/uranium. Last Updated: December 3, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 2, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

The lucky life of John Steele and America’s earliest oil wealth.

John Washington Steele’s good fortune began on December 10, 1844, when Culbertson and Sarah McClintock adopted him as an infant. The McClintocks also adopted his sister Permelia, bringing both home to the farm along Oil Creek in Venango County, Pennsylvania.

Fifteen years later, the U.S. petroleum industry began with a 69.5-foot-deep oil discovery at nearby Titusville, the first oil well drilled commercially for distilling into kerosene (also called coal oil).

Pennsylvania petroleum reserves revealed at Oil Creek made the widow McClintock a fortune in royalties. When she died in a kitchen fire in 1864, Mrs. McClintock left her oil wealth to her only surviving child, Johnny, who inherited $24,500 at age 20.

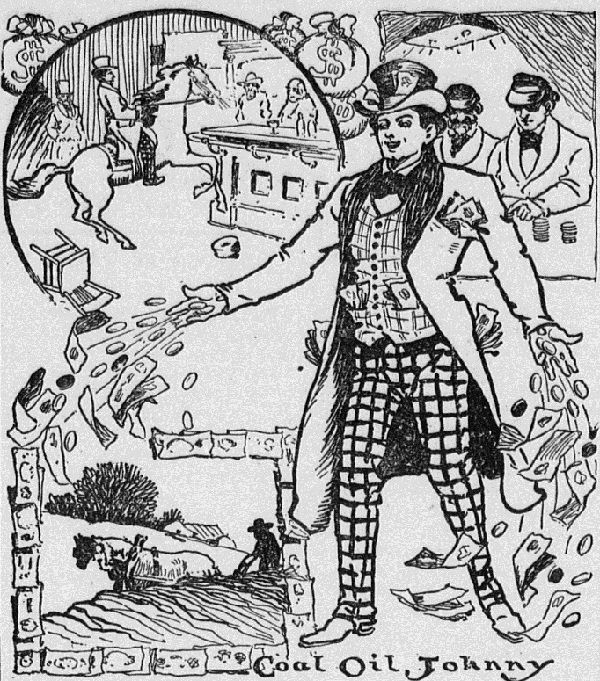

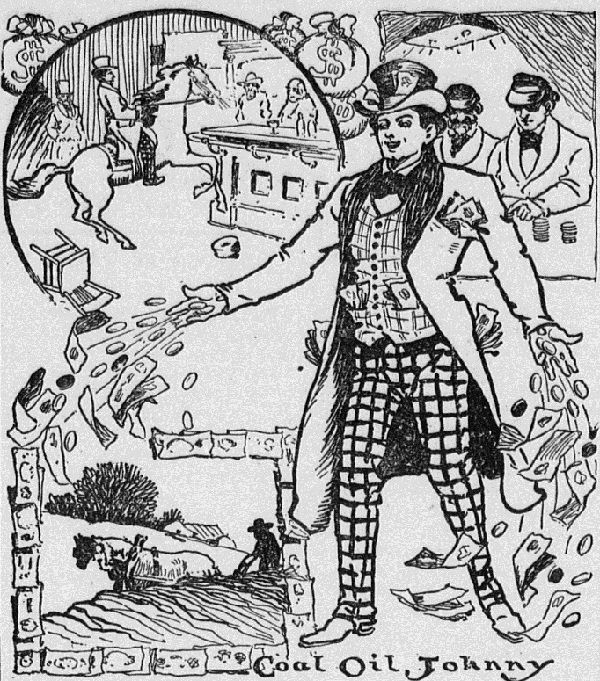

John Washington Steele of Venango County, Pennsylvania, inherited oil riches.

Johnny also inherited his mother’s 200-acre farm along Oil Creek between the now Rynd Farm and the small community of Rouseville, south of 15-miles Titusville. The farm already included 20 producing oil wells yielding $2,800 in royalties every day.

Rouseville was where future muckraking journalist Ida Minerva Tarbell (1857-1944) lived in 1861, when a gushing well erupted into flames — resulting in an early petroleum industry tragedy (see Rouseville 1861 Oil Well Fire).

Legendary Extravagance

“Coal Oil Johnny” Steele would earn his famous name in 1865 — after less than one year of extravagance, according to the New York Times.

“In his day, Steele was the greatest spender the world had ever known,” the newspaper proclaimed. “He threw away $3,000,000 in less than a year.”

Philadelphia journalists coined the name “Coal Oil Johnny” for him, reportedly because of his attachment to a custom carriage that had black oil derricks spouting dollar symbols painted on its red doors. He later confessed in his autobiography:

I spent my money foolishly, recklessly, wickedly, gave it away without excuse; threw dollars to street urchins to see them scramble; tipped waiters with five and ten dollar bills; was intoxicated most of the time, and kept the crowd surrounding me usually in the same condition.

“Before J.R. Ewing, or the Beverly Hillbillies, or even John D. Rockefeller, there was Coal Oil Johnny,” noted a 2010 article in The Atlantic.

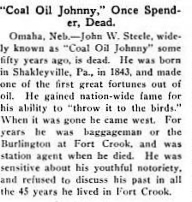

Such wealth could not last forever, but the rise and fall of Coal Oil Johnny, who died in modest circumstances in 1920 at age 76, has lingered in America’s petroleum history.

In 2010, The Atlantic magazine published “The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny, America’s Great Forgotten Parable,” an article sympathetic to his riches-to-rags story. It describes the country’s fascination with the earliest economic booms brought by “black gold” discoveries in Pennsylvania.

“Before J.R. Ewing, or the Beverly Hillbillies, or even John D. Rockefeller, there was Coal Oil Johnny,” noted the October 18 feature story. “He was the first great cautionary tale of the oil age — and his name would resound in popular culture for more than half a century after he made and lost his fortune in the 1860s.”

Refurbished boyhood home of “Coal Oil Johnny” at Oil Creek State Park (and train station) north of Rouseville, Pennsylvania. Photo by Bruce Wells.

For generations after the peak of his career, Johnny was still so famous that any major oil strike — especially the January 1901 gusher at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas — “brought his tales back to people’s lips,” noted the magazine article, citing Brian Black, a historian at Pennsylvania State University.

“It was wealth from nowhere,” Black explained. “Somebody like that was coming in without any opportunity or wealth and suddenly has a transforming moment. That’s the magic and it transfers right through to the Beverly Hillbillies and the rest of the mythology.”

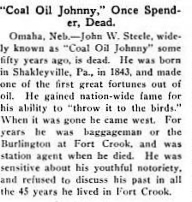

John W. Steele, who “made one of the first great fortunes out of oil,” died in 1920 in Nebraska.

“Coal Oil Johnny” was a legend, and like all legends, “he became a stand-in for a constellation of people, things, ideas, feelings and morals – in this case, about oil wealth and how it works,” he added.

“He made and lost this huge fortune – and yet he didn’t go crazy or do anything terrible. Instead, he ended up living a regular, content life, mostly as a railroad agent in Nebraska,” the 2010 Atlantic article concluded. “Surely there’s a lesson in that for the millions who’ve lost everything in the housing boom and bust.”

John Washington Steele’s Venango County home, relocated and restored by Pennsylvania’s Oil Region Alliance of Business, Industry & Tourism, stands today in Oil Creek State Park, just off Route 8, north of Rouseville.

On Route 8 south of Rouseville is the still-producing McClintock No. 1 oil well. “This is the oldest well in the world that is still producing oil at its original depth,” proclaims the Alliance. “Souvenir bottles of crude oil from McClintock Well Number One are available at the Drake Well Museum, outside Titusville.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny (2007); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/legend-of-coal-oil-johnny. Last Updated: December 4, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 1, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Remembering contributions of all petroleum industry pioneers.

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS), community museums, and professional associations have sought ways to preserve written histories of the men and women who have worked in the industry. Many museum have established oral (and video) history collections.

Sharing Your Story

AOGHS offers an outreach resource for those wanting to share their career experiences in the petroleum industry. When contacted with family stories, the historical society tries to post some of the personal oilfield stories of women, including oilfield crew leader Tamara George.

Women working in the petroleum industry greatly multiplied following Title IX, the 1972 federal civil rights law prohibiting sex-based discrimination in any education program or activity receiving federal funding.

Helping add to this chronicle of oilfield women pioneers, a 2020 email from the son of Lynda Armstrong noted her working as a roustabout for Gulf Oil in 1974.

Lynda Armstrong: Gulf Oil Roustabout

In the 1970s, Lynda Armstrong, Tamara George, and other determined women were pioneers in working in the male-dominated petroleum industry — upstream and downstream, onshore and offshore (see Women of the Offshore Petroleum Industry tell Their Stories).

In August 2020, John Armstrong described his late mother’s accomplishments in an email to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. He reported that In 1974, Lynda Armstrong worked in Goldsmith Texas, outside of Odessa, “as a roustabout for Gulf Oil before becoming the foreman for the water injection plant that is located on the Y.T .Ranch in Goldsmith.”

“I blazed a few trails in my days,” noted the late Lynn Armstrong about her oilfield career.

Armstrong would go on to teach corrosion technology at Odessa College and Eastern New Mexico University. “I blazed a few trails in my days,” she later explained about her oil patch career.

Armstrong said she was among the first women in 1974 to be hired as a roustabout by Gulf Oil. She later became an Arco lease operator; and Enserch production supervisor; a production technology instructor; and a technology instructor at Odessa College, Texas.

Tamara George: Roustabout Crew Leader

In early 1980s in Texas Panhandle oilfields, Tamara L. George led a skilled service company crew. Among the very first women to hold the dangerous, labor-intensive job, her oilfield journey began at D-J’s Roustabout and Well Services in Borger, Texas.

“At the time two brothers owned the company, Jerry Nolan, who handled the office work, and Harold Nolan, who did everything outside the office, George explained in a December 2018 email to AOGHS.

“It was Harold Nolan who wanted to hire me, but Don Nolan was not keen on this idea thinking I would be problems that I could not handle the work, get along with the men,” she added. “Don did not know I had been an Industrial, commercial and residential electrician, apprentice iron welder, and an auto body technician.”

The Hutchinson County Historical Museum in Borger exhibits the oilfield boom of the 1930s. Photo by Bruce Wells.

She said Nolans gave her a chance, and “within six months I moved to being a roustabout foreman running my own crew,” George explained in her note to the historical society. “I was the most requested crew in the Texas Panhandle oilfields.”

After leading her crews in the 1980s, George has proclaimed herself to be “only woman to ever hold such a position,” and even the “first woman to be a roustabout foreman in oilfield history!” Her personal oilfield record (which she is still researching) may extend to Canada, where she worked a few months as a roustabout foreman for Pangea Oil & Gas Company of Calgary, Alberta. And there’s still more to her career firsts.

“When the oilfield shut down, I went into medicine,” she noted, adding that she returned to school to work on advanced degrees in radiology and gastroenterology. Then came a personal health crisis.

“I was around two years into obtaining my doctorates when a fatal tumor revealed itself,” George explained. “The tumor had caused a rather large aneurysm to which the doctors shook their heads in disbelief.” It was a mystery to her doctors how the roustabout foreman survived while doing such labor intensive work of the oil industry. In the years since her service company work, George, who today lives in Elk City, Oklahoma, has “not come across any women doing what I did” earlier in the oilfields.

Oil History of Borger, Texas

Thousands of people rushed to the Texas Panhandle in early 1926 after Dixon Creek Oil and Refining Company completed the Smith No. 1 well, which flowed at 10,000 barrels of oil a day in southern Hutchinson County.

A.P. “Ace” Borger of Tulsa, Oklahoma, leased a 240-acre tract and by September his Borger oilfield had more than 800 producing wells, yielding 165,000 barrels a day

Dedicated in 1977, the Hutchinson County Boom Town Museum in Borger today celebrates “Oil Boom Heritage” every March. Special exhibits, events and school tours occur throughout the Borger celebration, about 40 miles northeast of Amarillo.

______________________

Recommended Reading: Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Women Oilfield Roustabouts.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/women-oilfield-roustabouts. Last Updated: January 8, 2026. Original Published Date: December 6, 2018.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 28, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Rise and fall of an infamous Pennsylvania boomtown.

As the Civil War ended, oil discoveries at Pithole Creek in Pennsylvania created a headline-making boomtown for the young petroleum industry. As wells reached deeper into geological formations, the first gushers arrived — adding to “black gold” fever sweeping the country.

America’s oil production began in 1859 when Edwin L. Drake completed the first commercial well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. Drilled near natural oil seeps, his oilfield discovery at a depth of 69.5 feet led to a rush of exploration in the remote Allegheny River Valley.

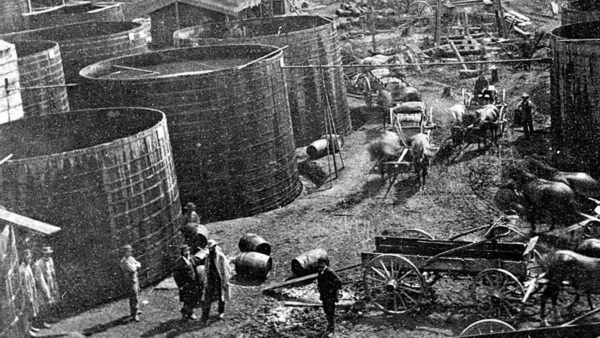

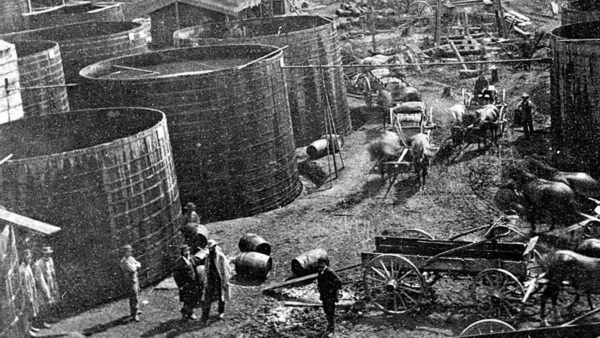

The new petroleum industry’s transportation infrastructure struggled as oil tanks crowded Pithole, Pennsylvania. In 1865, the first oil pipeline linked an oil well to a railroad station about five miles away. Photo by the “Oil Creek Artist,” John Mather, courtesy Drake Well Museum.

In 1864, businessman Ian Frazier found success along Cherry Creek, another small watercourse with signs of oil. After making a quick $250,000, Frazier looked for another opportunity for providing oil to new Pittsburgh refineries making kerosene for lamps.

Frazier hired a diviner to search along Pithole Creek, which smelled like “sulfur and brimstone,” according to historian Douglas Wayne Houck. “He went to the creek and followed the diviner around until the forked twig dipped, pointing to a specific spot on the ground,” Houck noted in 2014.

Although exploration techniques would improve, the science of petroleum geology was still in the future. Oil companies (and soon natural gas) had already begun drilling the “dry holes.”

Gusher at Pithole Creek

The first well of Ian Frazier’s United States Oil Company found no oil. A second well — drilled using the same steam-powered, cable-tool technology — erupted spectacularly on January 7, 1865, producing 650 barrels of oil a day. The Frazier well, the first U.S. oil gusher, brought a flood of drillers and speculators to Pithole Creek.

Two more wells erupted black geysers on January 17 and January 19, each flowing at about 800 barrels of oil a day (the invention of a practical blowout preventer was still half a century away). United States Oil Company subdivided its property and began selling lots for $3,000 per half-acre plot.

The Titusville Herald proclaimed Pithole as having “probably the most productive wells in the oil region of Pennsylvania, Houck explained in his Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York. Fortunes were being made and lost in the oil regions (see the Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny”).

As the news spread through Venango County, “everyone came to the Pithole area to try their luck,” noted one reporter. Many were Confederate and Union war veterans. And as more successful wells came in, about 3,000 teamsters rushed to Pithole to haul out the rapidly multiplying barrels of oil.

Managed by the Drake Well Museum, the Pithole Visitors Center includes a diorama of the vanished town. Photo by Bruce Wells.

There were many reasons behind the Pithole oil boom, including a flood of paper money at the end of the Civil War. Returning Union veterans had currency and were eager to invest — especially after reading newspaper articles about oil gushers and boomtowns. Thousands of veterans also wanted jobs after long months on army pay.

By May 1865, the town was home to 57 hotels, many shops, and its own daily newspaper. It had the third busiest post office in Pennsylvania — handling 5,500 pieces of mail a day.

Pithole’s Lady Macbeth

In December 1865, Shakespearean tragedienne Miss Eloise Bridges appeared as Lady Macbeth in America’s first famously notorious oil boomtown.

Shakespearean tragedienne Eloise Bridges appeared on the Pithole stage in 1865.

Bridges appeared at Murphy’s Theater, the biggest building in a town of more than 30,000 teamsters, coopers, lease-traders, roughnecks, and merchants. Three stories high, the building had 1,100 seats, a 40-foot stage, an orchestra, and chandelier lighting by Tiffany.

Bridges was the acclaimed darling of the Pithole stage. Eight months after she departed for new engagements in Ohio, the oilfield at Pithole ran dry; the most famous U.S. boomtown collapsed into empty streets and abandoned buildings.

Pennsylvania oil region visitors today walk the grassy streets of the first oil boom’s ghost town.

First Oil Pipeline

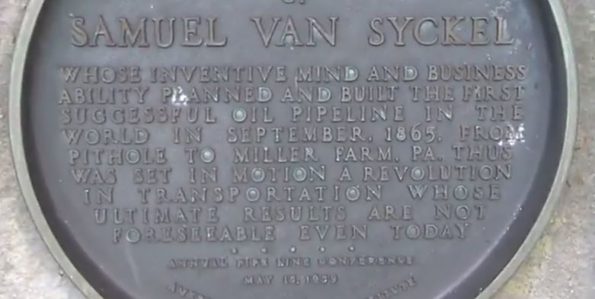

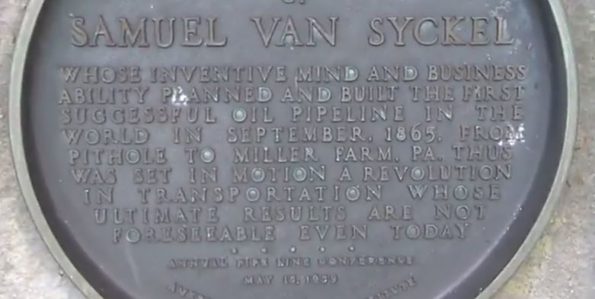

As Pithole oil tanks overflowed (and tank fires from accidents and lightning strikes increased), petroleum shipper Samuel Van Syckel conceived an infrastructure solution that became an engineering milestone.

In 1865, his newly formed Oil Transportation Association put into service a two-inch iron line linking the Frazier well to the Miller Farm Oil Creek Railroad Station, about five miles away.

The American Petroleum Institute in 1959 dedicated a plaque on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum as part of the U.S. oil centennial.

“The day that the Van Syckel pipe-line began to run oil a revolution began in the business. After the Drake well it is the most important event in the history of the Oil Regions,” declared Ida Tarbell about the technology in her 1904 book, History of the Standard Oil Company.

Widely known as a known magazine journalist and a Lincoln biographer, Tarbell grew up in the area. Her family lived in Rouseville in 1861 when a gushing well erupted into flames — an early oilfield tragedy.

With 15-foot welded joints and three 10-horsepower Reed and Cogswell steam pumps, the pipeline transported 80 barrels of oil per hour — the equivalent of 300 teamster wagons working for 10 hours. Convinced their livelihood was threatened, teamsters attempted to sabotage the oil pipeline until armed guards intervened.

Unfortunately for Van Syckel, Pithole oil storage tanks frequently caught fire even as the Frazier well production began to decline. Other wells were beginning to run dry when, in 1866, fires spread out of control and burned 30 buildings, 30 oil wells, and 20,000 barrels of oil.

Pithole City

“Pithole’s days were numbered,” concluded historian Houck about the fire, which was documented by early oilfield photographer John Mather. “Buildings were taken down and carted off. A few people hung around until 1867.”

Visitors walk the grassy paths of Pithole’s former streets and see artifacts, including antique steam boilers. Volunteers “mow the streets.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

From beginning to end, America’s famous oil boomtown had lasted about 500 days. Pithole was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 20, 1973.

A visitors center added in 1975 contains exhibits, including a scale model of the city at its peak and a small theater. Volunteers “mow the streets” on the hillside so that tourists can stroll where the petroleum boomtown once flourished.

“Pithole City is known in the Pennsylvania oil region as the oil boomtown that vanished as quickly as it appeared,” notes the Drake Well Museum, which manages Historic Pithole City. Among the region’s earliest and most infamous investors was John Wilkes Booth (see the Dramatic Oil Company).

Oil Town Aero Views

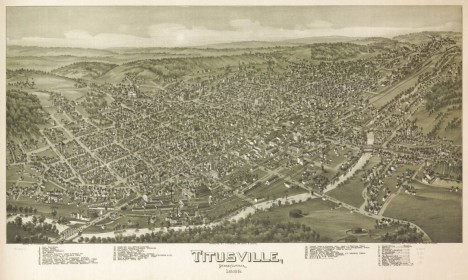

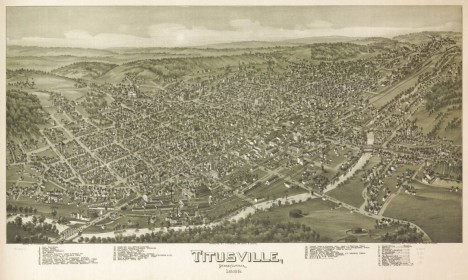

During the late 19th century, “bird’s-eye views” became a widely popular way to map U.S. cities and towns. Cartographer Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created many of the best panoramic maps that he also called “aero views.”

The wealthy Pennsylvania oil regions attracted the attention of Fowler, who in 1885 moved his family to Morrisville, where he worked for the next 25 years.

An 1896 Pennsylvania “aero view” map by Thaddeus M. Fowler, courtesy Library of Congress.

Fowler drew maps of Titusville, Oil City, and many petroleum-related boomtowns in West Virginia, Ohio — and Texas, where he created dozens of views of cities from 1890 to 1891.

But by far, most of the Fowler maps feature Pennsylvania cities between 1872 and 1922. There are 250 examples of his work in the collection of the Library of Congress. Learn more in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York (2014); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny

(2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny (2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Boom at Pithole Creek.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/pithole-creek/. Last Updated: November 29, 2025. Original Published Date: March 15, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 23, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

The piano teacher who drilled wells — and took over the Los Angeles oil market.

“A woman with a genius for affairs – it may sound paradoxical, but the fact exists. If Mrs. Emma A. Summers were less than a genius she could not, as she does today, control the Los Angeles oil markets.” – July 21, 1901, San Francisco Call newspaper.

Emma A. McCutchen Summers would become a woman to be reckoned with in the early Los Angeles petroleum industry. A refined Southern lady who graduated from Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music, Summers moved to Los Angeles in 1893 to teach piano. (more…)

(1959); Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman (2004). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.