by Bruce Wells | Jan 20, 2026 | Petroleum Pioneers

When a Fort Worth independent producer completed a remote wildcat well in East Texas on January 26, 1931, the well revealed the true extent of an oilfield discovered months earlier and many miles away.

As the Great Depression worsened and East Texas farmers struggled to survive, W.A. “Monty” Moncrief and two partners drilled the Lathrop No. 1 well in Gregg County. When completed in 1931, their well produced 320 barrels of oil per hour from a depth of 3,587 feet.

Far from what earlier were thought to be two oilfield discoveries — this third well producing 7,680 barrels a day revealed a “Black Giant.”

A circa 1960 photograph of W.A. “Monty” Moncrief and his son “Tex” in Fort Worth’s Moncrief Building.

Moncrief, who had worked for Marland Oil Company in Fort Worth after returning from World War I, drilled in a region (and at a depth) where few geologists thought petroleum production a possibility. He and fellow independent operators John Ferrell and Eddie Showers thought otherwise.

The third East Texas well was completed 25 miles north of Rusk County’s already famous October 1930 Daisy Bradford No. 3 well drilled by Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner northwest of Henderson (and southeast New London, site of a tragic 1937 school explosion).

Moncrief’s oil discovery came 15 miles north of the Lou Della Crim No. 1 well, drilled three days after Christmas, on “Mama” Crim’s farm about nine miles from the Joiner well. At first, the distances between these “wildcat” discoveries convinced geologists, petroleum engineers (and experts at the large oil companies) the wells were small, separate oilfields. They were wrong.

Three Wells, One Giant Oilfield

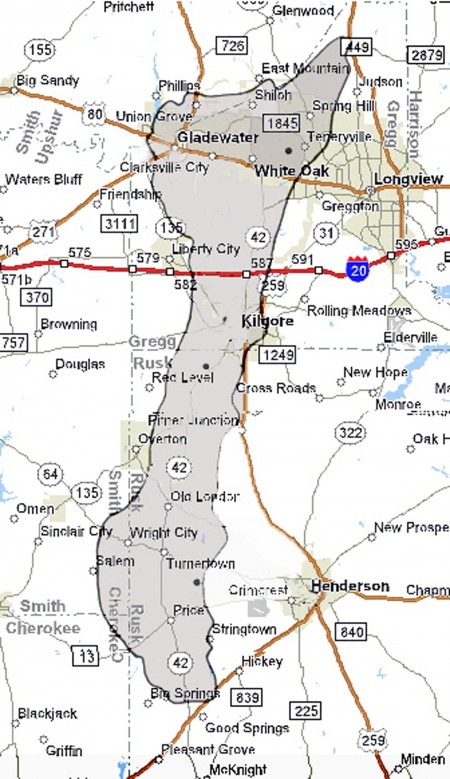

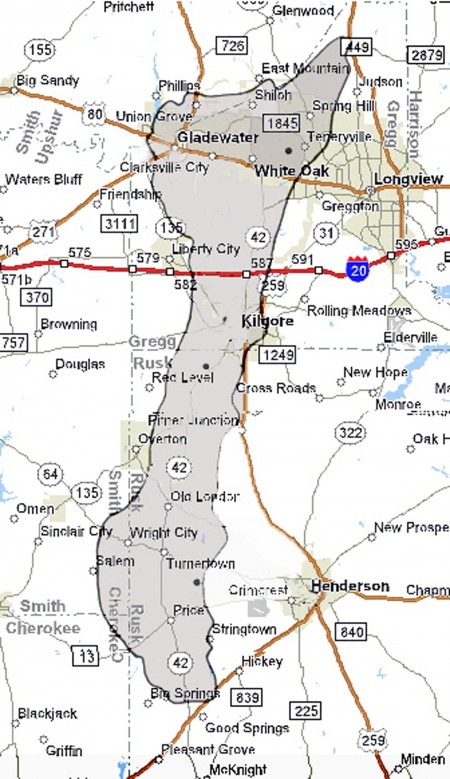

To the delight of other independent producers and many small, struggling farmers, Moncrief’s Lathrop discovery showed that the three wells were part of a single petroleum-producing field. Further development and a forest of steel derricks revealed the northernmost extension of the 130,000-acre East Texas oilfield.

The history of the petroleum industry’s gigantic oilfield has been preserved at the East Texas Oil Museum, which opened at Kilgore College in 1980. Joe White, the museum’s founding director, created exhibit spaces for the “authentic recreation of the oil discoveries and production in the early 1930s in the largest oilfield inside U.S. boundaries.”

After more than half a century of major discoveries, William Alvin “Monty” Moncrief died in 1986. His legacy has extended beyond his good fortune in East Texas.

The family exploration business established by Moncrief in 1929 would be led by sons W.A. “Tex” Moncrief Jr. and C.B. “Charlie” Moncrief, who grew up in the exploration business. In 2010, Forbes reported that 94-year-old “Tex” made “perhaps the biggest find of his life” by discovering an offshore field of about six trillion cubic feet of gas.

Moncrief Philanthropy

Hospitals in communities near the senior Moncrief’s nationwide discoveries, including a giant oilfield in Jay, Florida, revealed in 1970, and another in Louisiana, have benefited from his drilling acumen.

The 130,000-acre East Texas oilfield became the largest in the contiguous United States in 1930.

Moncrief and his wife established the William A. and Elizabeth B. Moncrief Foundation and the Moncrief Radiation Center in Fort Worth, as well as the Moncrief Annex of the All Saints Hospital. Buildings in their honor have been erected at Texas Christian University, All Saints School, and Fort Worth Country Day School.

Dr. Daniel Podolsky in 2013 presented W.A. “Tex” Moncrief Jr. with a framed image of the new Moncrief Cancer Institute at the Fort Worth facility’s dedication ceremony.

Supported throughout the 1960s and 1970s by the Moncrief family, Fort Worth’s original Cancer Center, known as the Radiation Center, was founded in 1958 as one of the nation’s first community radiation facilities.

In 2013, the $22 million Moncrief Cancer Institute was dedicated during a ceremony attended by “Tex” Moncrief Jr. “One man’s vision for a place that would make life better for cancer survivors is now a reality in Fort Worth,” noted one reporter at the dedication of the 3.4-acre facility at 400 W. Magnolia Avenue.

Small investments from hopeful Texas farmers brought historic results — and prosperity to Kilgore, Longview, and Tyler during the Great Depression. Kilgore annually celebrates its oil heritage.

Early Days in Oklahoma

Born in Sulphur Springs, Texas, on August 25, 1895, Moncrief grew up in Checotah, Oklahoma, where his family moved when he was five. Checotah was the town where Moncrief attended high school, taking typing and shorthand — and excelling to the point that he became a court reporter in Eufaula, Oklahoma.

To get an education, Moncrief saved $150 to enroll at the University of Oklahoma at Norman, where he worked in the registrar’s office. He became “Monty” after his initiation into the Sigma Chi fraternity.

During World War I, Moncrief volunteered and joined the U.S. Cavalry. He was sent to officer training camp in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he met and, six months later, married Mary Elizabeth Bright on May 28, 1918. Sent to France, Moncrief saw no combat thanks to the Armistice being signed before his battalion reached the front.

After the war, Moncrief returned to Oklahoma, where he found work at Marland Oil, first in its accounting department and later in its land office. When Marland opened offices in Fort Worth in the late 1920s, Moncrief was promoted to vice president for the new division.

In 1929, Moncrief would strike out on his own as an independent operator. He teamed up with John Ferrell and Eddie Showers, and they bought leases where they ultimately drilled the successful F.K. Lathrop No. 1 well.

C.M. “Dad” Joiner’s partner, the 300-pound self-taught geologist A.D. “Doc” Lloyd, had predicted the field would be four to ten miles wide and 50 to 50 miles long, according to Moncrief, interviewed in 1985 for Wildcatter: A Story of Texas Oil.

“Of course, everyone at the time thought he was nuts, including me,” the Texas wildcatter added. Also interviewed, museum founder Joe White said Lloyd’s assessment predicted the Woodbine sands at a depth of 3,550 — about two thousand feet shallower than major oil company geologists believed.

Moncrief’s Lathrop January 1931 wildcat well, which produced from the Woodbine formation at a depth of 3,587 feet, proved the oilfield stretched 42 miles long and up to eight miles wide — the largest in the lower 48 states.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skulduggery & Trivia (2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2003); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Moncrief makes East Texas History.” Authors: B.A. and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/moncrief-oil. Last Updated: January 19, 2026. Original Published Date: January 25, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 4, 2026 | Petroleum Pioneers

Oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover in the 1920s launched the Arkansas petroleum industry.

Arkansas oil wells of the 1920s created boom towns, established the state’s petroleum exploration and production industry, and boosted the career of a young wildcatter named Haroldson Lafayette Hunt.

The first Arkansas well that yielded “sufficient quantities of oil” was the Hunter No. 1 of April 16, 1920, in Ouachita County, according to the Arkansas Geological Survey. Natural gas was discovered a few days later in Union County by Constantine Oil and Refining Company.

Surrounded by 20 acres of woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in the Smackover oilfield preserves the state’s petroleum history seven miles north of equally historic El Dorado.

A January 1921 well drilled in the same Union County field at El Dorado marked the true beginning of commercial oil production in Arkansas. When the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well struck oil in 1921, the oilfield discovery soon catapulted the population of El Dorado from 4,000 to 25,000 people. The well, 15 miles north of the Louisiana border, was the state’s first commercial oil well.

“Twenty-two trains a day were soon running in and out of El Dorado,” noted the Arkansas Gazette. An excited state legislature announced plans for a special railway excursion for lawmakers to visit the oil well in Union County.

Meanwhile, Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt arrived from Texas with $50. He joined the crowd of lease traders and speculators at the Garrett Hotel, where fortunes were being made — and lost. Hunt launched his start as an independent oil and natural gas producer during the El Dorado drilling boom.

Some locals said it was his expertise at the poker table that earned him enough to afford a one-half acre parcel lease where his Hunt-Pickering No. 1 well produced some oil but ultimately proved unprofitable.

Hunt persevered and within four years acquired substantial El Dorado and Smackover oilfield holdings. By 1925, he was a successful 36-year-old oilman with his wife Lyda and three young children living in a three-story El Dorado home. He would significantly add to his oilfield successes a decade later in Kilgore, Texas (learn more in East Texas Oilfield Discovery).

Giant Oilfield at El Dorado

Located on a hill a little over a mile southwest of El Dorado, the derrick was visible from the town, according to historians A.R. and R.B. Buckalew. They write that three “gassers” had been completed in the general vicinity but did not produce in commercial quantities.

There was no market for natural gas at the time, the authors explained in their 1974 book, The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924.

The Garrett Hotel, where H.L. Hunt checked in with 50 borrowed dollars and launched his long career as a successful independent oil producer.

Yet Dr. Samuel T. Busey was convinced “there was oil down there somewhere.”

The authors added, “Among those who gambled their savings with Busey at this time were Wong Hing, also called Charles Louis, a Chinese laundry man, and Ike Felsenthal, whose family had created a community in southeast Union County in earlier years.”

With no oil production nearby, investing in the “wildcat” well was a leap of faith. Chal Daniels, who was overseeing drilling operations for Busey, contributed the hefty sum of $1,000. On January 10, 1921, the well had been drilled to 2,233 feet and reached the Nacatoch Sand. A small crowd of onlookers and the drilling crew — after moving a safe distance away — watched and listened.

“The spectators, among them Dr. Busey, watched with an air of expectancy,” noted the historians. “Drilling had ceased and bailing operations had begun to try to bring in the well. At about 4:30 p.m., as the bailer was being lifted from its sixth trip into the deep hole, a rumble from deep in the well was heard.”

The rumbling grew in intensity, “shaking the derrick and the very ground on which it stood as if an earthquake were passing,” the authors report. “Suddenly, with a deafening roar, ‘a thick black column’ of gas and oil and water shot out of the well,” they added.

The gusher blew through the derrick and “bursts into a black mushroom” cloud against the January sky. The Busey No. 1 well produced 15,000,000 to 35,000,000 cubic feet of gas and from 3,000 to 10,000 barrels of oil and water a day.

Petroleum brings Prosperity

Thanks to the El Dorado discovery, the first Arkansas petroleum boom was on. By 1922, there were 900 producing wells in the state.

Civic leaders raised funds to preserve El Dorado’s historic downtown — and add an Oil Heritage Park at 101 East Main Street.

“Three months after the Busey well came in, work was underway on an amusement park located three blocks from the town that would include a swimming pool, picnic grounds, rides and concessions,” noted the Union County Sheriff’s Office. “Culture was not forgotten as an old cotton shed in the center of town near the railroad tracks was converted to an auditorium.”

The 68-square-mile field will lead U.S. oil output in 1925 — with production reaching 70 million barrels. “It was a scene never again to be equaled in El Dorado’s history, nor would the town and its people ever be the same again,” the authors concluded. “Union County’s dream of oil had come true.”

In 2002, El Dorado gathered 40 local artists to paint 55 oil drums donated by the local Murphy Oil Company. Preserving the town’s historic assets, including boom-era buildings, remains a major goal of the local group, Main Street El Dorado, which was the “2009 Great American Main Street Award Winner” of the National Trust Main Street Center.

Second Oil Boom: Discovery at Smackover

Prior to the January 1921 El Dorado discovery, the region’s economy relied almost exclusively on the cotton and timber industries “that thrived in the vast virgin forests of southern Arkansas.”

Petroleum wealth helped Smackover, Arkansas, incorporate in 1922.

Six months after the Busey-Armgstrong No. 1 well, another giant oilfield discovery 12 miles north will bring national attention — and lead to the incorporation of Smackover. A small agricultural and sawmill community with a population of 131, Smackover had been settled by French fur trappers in 1844. They called the area “Sumac-Couvert,” meaning covered with sumac or shumate bushes.

According to historian Don Lambert, by 1908 Sidney Umsted operated a large sawmill and logging venture two miles north of town. He believed that oil lay beneath the surface. “On July 1, 1922, Umsted’s wildcat well (Richardson No. 1) produced a gusher from a depth of 2,066 feet,” Lambert reported.

“Within six months, 1,000 wells had been drilled, with a success rate of ninety-two percent. The little town had increased from a mere ninety to 25,000, and its uncommon name would quickly attain national attention,” added Lambert.

Roughnecks photographed following the July 1, 1922, discovery of the Smackover (Richardson) field in Union County. Courtesy of the Southwest Arkansas Regional Archives.

The oil-producing area of the Smackover field covered more than 25,000 acres. By 1925, it had become the largest-producing oil site in the world. The field will produce 583 million barrels of oil by 2001.

Opened in 1986, the Arkansas Natural Resources Museum educates visitors in the heart of the historic Smackover oilfield. Exhibits explain how the Busey No. 1 well near El Dorado “blew in with a gusty fury” in January 1921.

The museum includes a five-acre Oilfield Park with operating examples of early and modern oil-producing technologies. They can be found one mile south of the once petroleum-rich town of Smackover, which has celebrated its petroleum heritage with an “Oil Town Festival” every June.

Abundant natural gas in the Fayetteville shale formation brought more drilling to Arkansas.

With more than 46,800 wells drilled between 1925 and 2023, about one-third of the 75 Arkansas counties have produced oil and/or natural gas, reported Mineralsanswers.com in July 2024.

Southern Arkansas also is considered among the most prolific lithium resources of its type in North America, according to ExxonMobil, which in 2023 acquired the rights to 120,000 gross acres of the Smackover formation.

Fayetteville Shale

Thanks to advances in drilling technologies combined with hydraulic fracturing, the Fayetteville Shale — a 50-mile-wide formation across central Arkansas — has added vast natural gas reserves while creating a new petroleum boom for the state.

Unlike traditional fields containing hydrocarbons in porous formations, shale holds natural gas in a fine-grained rock or “tight sands.” Until the 1990s, drilling in most shale formations was not considered profitable for production.

Surrounded by 20 acres of lush woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources collects and exhibits southern Arkansas petroleum — along with the history of brine drilling and the salt industry. It also has documented the social and economic histories that accompanied the 1920s oil boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924 (1974); The Three Families of H. L. Hunt (1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Arkansas Oil Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/arkansas-oil-and-gas-boom-towns. Last Updated: January 3, 2026. Original Published Date: April 21, 2013.