by Bruce Wells | Jul 26, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

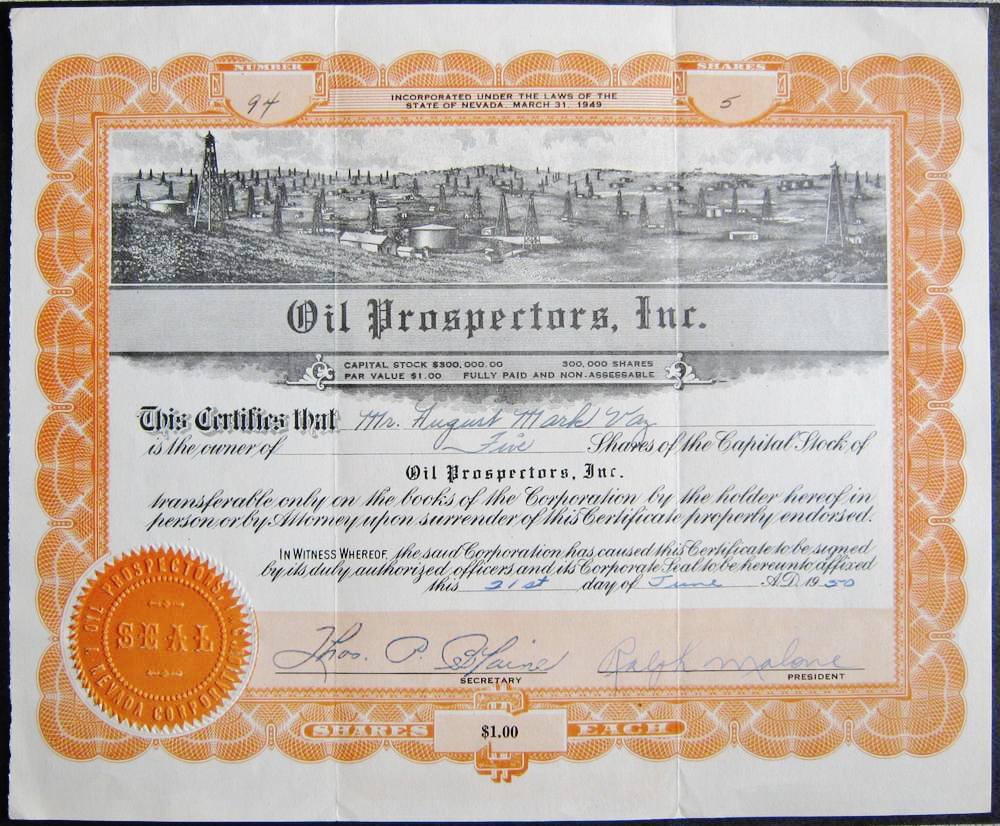

Although geologists, petroleum engineers and other earth scientists were far more helpful for finding “black gold,” Oil Prospectors Inc. preferred unscientific methods to sway unwary investors.

During the Great Depression, some fortune seekers were convinced a “divining rod, a doodlebug, a switch, or a twig” could find oilfields. In the 1950s, others invested in doodlebug technology they were told came from flying saucers. Then as now, any “miraculous machine” could help fleece the gullible.

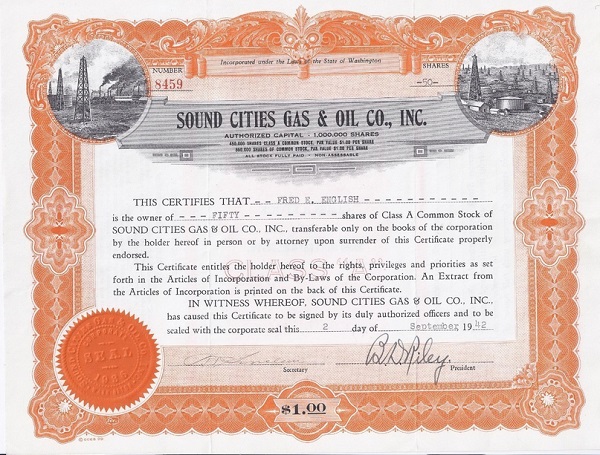

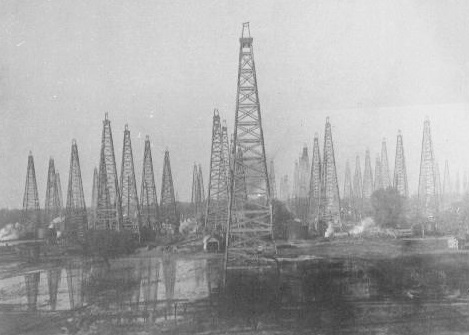

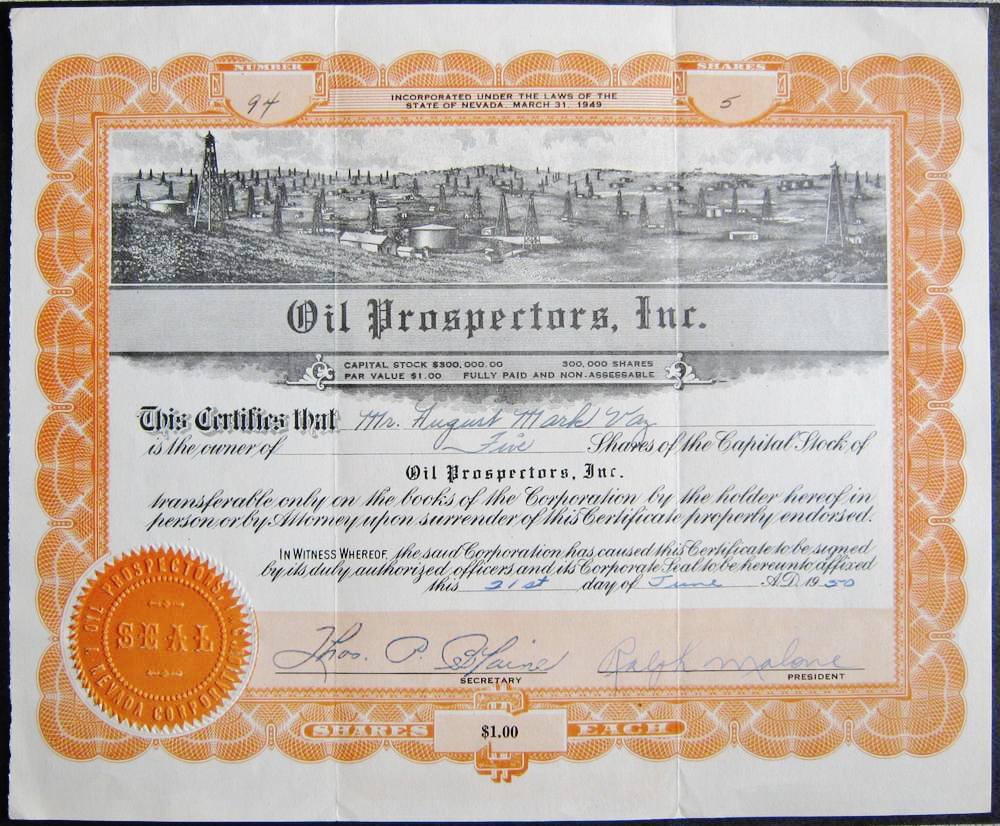

In the rush to print stock certificates during drilling booms, many companies printed certificates with a field of derricks vignette — often using the same artwork.

Not long after the December 1931 discovery of the Conroe, Texas, oilfield, a “doodlebug” device swindled Houston oil investors out of $20,000. It also sent Ralph Malone and Vivian Buie to jail in 1935.

During their trial in district court, a prosecution witness told of receiving letters describing the doodlebugger as capable of finding oil and natural gas in Polk County.

Malone and Buie claimed their device would find “another field like the Conroe field” worth millions of dollars. They described their doodlebug as “a wonderful instrument that could locate oil pools.”

Learn about Conroe’s oilfield in Technology and the “Conroe Crater.”

Despite their defense attorneys efforts, Malone and Buie (the alleged “brains” of the doodlebug scam), were convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to terms in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Then their defense attorneys were indicted as well.

While their former clients headed off to prison, Arthur Heemann and C. Ray Smith hired their own legal council. The new defense team asserted the accused, “merely were attorneys for the swindlers and did not participate in the scheme.”

It did not help that attorney Heemann had been charged five years earlier with the same crime while promoting the similarly fraudulent Oil Investors Company.

Nonetheless, the lawyers got the lawyers off when the judge ruled them not guilty on April 15, 1938. Two months later, Ralph Malone was transported from Leavenworth to a Tucson, Arizona, prison to finish his three-year sentence.

Doodlebugs, Magnetic Loggers, and Flying Saucers

Although Malone was absent from oil stock scams for several years, investors did not abandon their fascination with doodlebugs. The convicted con man resurfaced in the early 1950s when his penchant for mail fraud landed him in trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

“Often investigation is directed to highly objectionable sales literature which greatly over emphasize the possibilities of success from the proposed security purchase,” the SEC noted in its 17th annual report. “So it was in the case of Oil Prospectors, Inc. and Ralph Malone.”

One year later, the SEC again addressed the issue of doodlebugs, explaining the necessity of resorting to the courts to get compliance with the Securities Act.

“A substantial number of cases requiring injunctive action are those relating to oil and mining promotions,” noted the June 30, 1952, annual report. “The ‘gold brick’ aspect of many of these promotions has by now become quite stereotyped.” The SEC’s complaints seeking injunctions pointed out that, “sellers were omitting to disclose that these individuals had criminal records.”

The commission cited another example of “the almost perennial doodlebug” where the “defendants used in their operations a device called a ‘Magnetic Logger’ and the claims made for its efficacy in discovering oil were the usual ones and were false…There is reason to believe that the injunction obtained by the commission saved the investing public a substantial sum.”

An SEC injunction in 1951 finally brought an end to Oil Prospectors and Ralph Malone disappeared from the news. Doodlebug hoaxes continued.

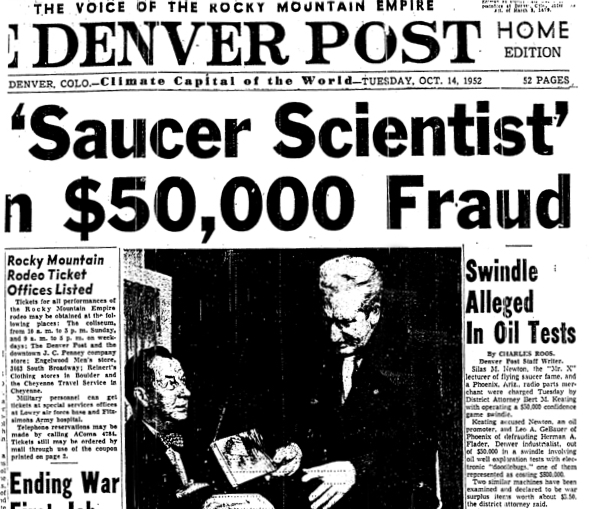

Most notably, Silas Newton and Leo GeBauer, claimed their doodlebug machine “operated on the same magnetic principles as the flying saucers.” The $800,000 contraption had been developed secretly by the government.

They promoted the tale of a 1948 flying saucer crash site near Aztec, New Mexico, that had yielded 16 humanoid bodies (Roswell’s aliens had reportedly arrived a year earlier).

Newton and GeBauer claimed the Aztec crash site included revolutionary technology for finding oil.

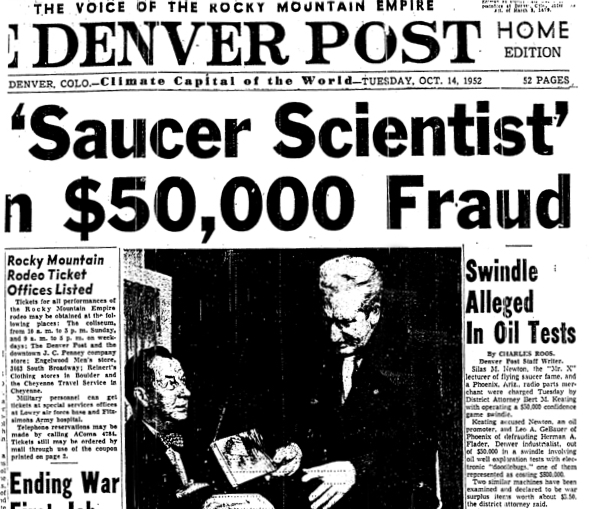

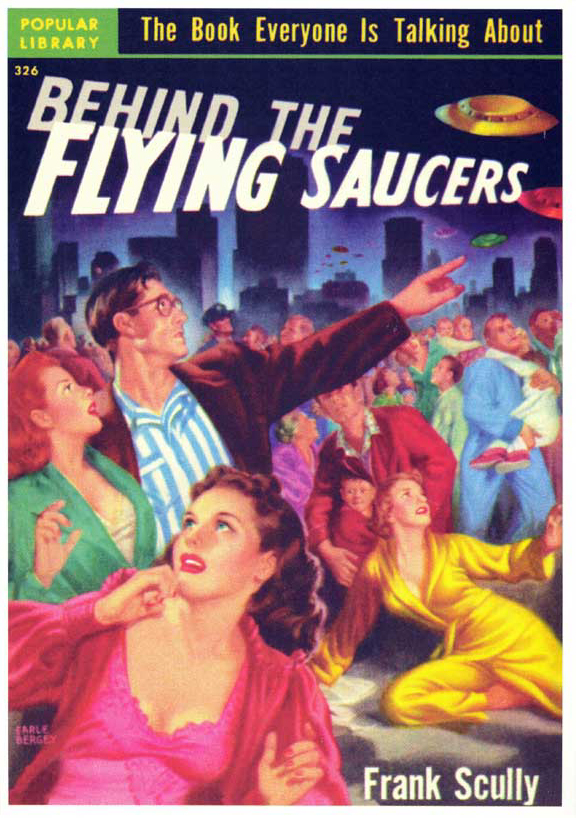

Silas Newton and Leo “Dr. Gee” GeBauer convinced author Frank Scully (at right) the government was hiding UFO crash sites and humanoid corpses. Investors believed their claims that a secret alien device could locate vast petroleum reserves.

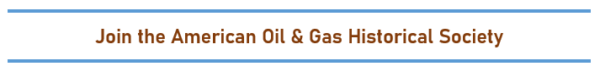

Although some still maintain an elaborate government cover-up has concealed the real Aztec UFO story, the petroleum exploration technology has received little mention. By 1952, the terrestrial luck of Newton and GeBauer ran out. The Denver Post’s October 14 headline proclaimed, “Saucer Scientist in $50,000 Fraud.”

In 1950 Frank Scully had published Behind Flying Saucers, a book reporting crashed UFOs (powered on magnetic principles) and the discovery of dead extraterrestrial beings.

In September 1952, True Magazine investigated Frank Scully, Silas Newton, and Leo GeBauer, the three principals involved in Scully’s best-selling book, Behind the Flying Saucers.

In 1952 and again in 1956, True magazine published articles that exposed doodlebug machine promoters Silas Newton and “Dr. Gee” (identified as Leo GeBauer) as “oil con artists who had hoaxed a gullible Scully,” according to the 1998 book, UFOs & Alien Contact: Two Centuries of Mystery.

It turned out the UFO inspired oil doodlebug was just a box covered in dials and switches made from $3.50 in surplus radio parts. The revelation brought little comfort to swindled investors.

Stock Certificate Derricks

Speculating in oil stocks has been hazardous since the first company incorporated in 1854 in Pennsylvania (see First American Oil Well). As drilling booms moved westward, thousands of exploration companies competed to exploit “black gold.” Most failed after a few expensive dry holes — or without drilling a single well.

Especially during the major oilfield discoveries beginning after World War I and continuing through the Great Depression, the rush to form oil companies led to certificates that looked remarkably alike. Printing boiler-plate stock certificates was not uncommon in the scramble to find investors.

For example, many short-lived companies’ stocks features the same artwork as Oil Prospectors Inc. Here are just a few:

Buck Run Oil and Refining

Buffalo-Texas Oil

Craven Oil and Refining

Evangeline Oil

Hog Creek Carruth Company

Texas Production Company

Modern Doodlebuggers

The Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG) published its first journal, Geophysics, in 1936. It included articles about the petroleum industry’s three major prospecting methods then used – seismic, gravity, and magnetic. All were based on the scientific method.

The journal’s lead article warned young geophysicists about employing “black magic” or “doodle-bug” methods based on unproven properties of oil, minerals or geological formations. “This is the first time that the term ‘doodle-bug’ was applied to scientific methods, particularly if they had no scientific validity, according to the 1982 book, Geophysics in the Affairs of Men.

“Twenty years later, it was a badge of honor to be known as a doodlebugger, i.e., the field personnel of geophysical crews,” noted the authors Charles C. Bates, T. F. Gaskell and R. B. Rice. “Still later, the term was applied to everyone who worked in exploration geophysics.”

A bronze statue, “The Doodlebugger,” welcomes visitors to the Society of Exploration Geophysicists headquarters in Tulsa. The name is a badge of honor for geophysical crews seeking oil. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Editor’s Note – The sculptor of the SEG statue, Jay O´Meilia of Tulsa, Oklahoma, also was the artist who created two “Oil Patch Warrior” statues – one in Ardmore and another across the Atlantic. See Roughnecks of Sherwood Forest.

More research and articles about U.S. exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Prospectors, Inc.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/oil-prospectors-inc. Last Updated: August 8, 2022. Original Published Date: May 13, 2016.

.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 22, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

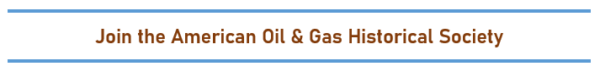

Washington state had never experienced significant commercial oil production until a wildcat well drilled by the Sound Cities Gas & Oil Company during the Great Depression. The company found just enough oil to instill oil fever about 40 miles south of Seattle.

Although West Coast oil seeps had led to major California oil discoveries, Washington (and Oregon) geology had frustrated exploration companies for decades. Sound Cities Gas & Oil, which had offices in Seattle and Tacoma, drilled near coal seams with seeps already producing flames.

Despite its advertised “modern scientific drilling operations” and exploration efforts near natural seeps, success eluded Sound Cities Gas & Oil Company.

Using a cable-tool drilling rig near the town of Enumclaw, the company drilled the Bobb No. 1 well seeking a hillside anticline. Geologists had long recognized anticlines – created by the up-folding of rocks, similar to an arch – as potential oil and natural gas traps. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Apr 20, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

Bandits and revolution in Mexico are not good for petroleum exploration.

National Oil Company of New Jersey (later the New National Oil Company of Delaware) originally formed in August 1910, as a holding company with multiple subsidiaries. The venture’s activities included shipping as well as oil exploration drilling operations in Texas, Louisiana — and during the Mexican Revolution.

Further, a subsidiary National Oil Company of Mexico (formerly Cie Exploradora Del Petroleo) held title to about 36,000 acres of oil-produing land as well as a tidewater terminal and other facilities on the Panuco River near Tampico, Mexico.

The leases on La Herradura and Los Chijoles came under attack during Mexico’s revolutionary period. On April 17, 1914, Constitutionalist forces raided, appropriated livestock and equipment, and forced the company to abandon a 30,000 barrel a day gusher that had yet to be capped. They returned 30 days later, but negotiations with Mexico over damages would last for decades. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Mar 7, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

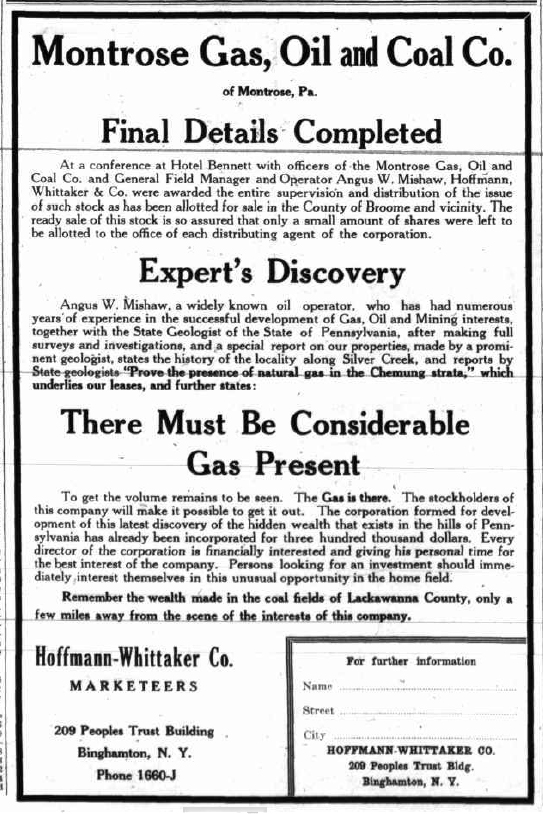

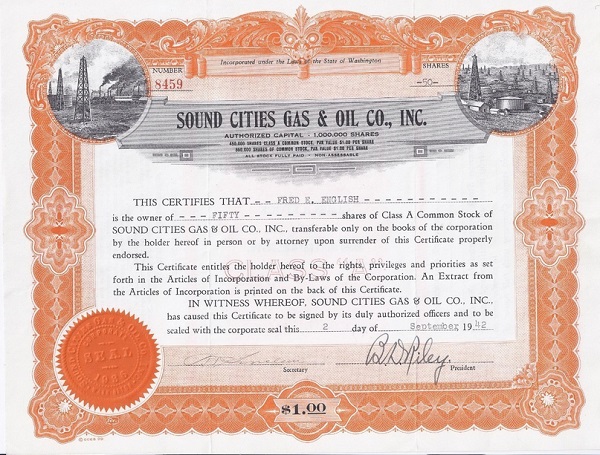

The earliest U.S. petroleum exploration companies learned to look for natural seeps. A decade before the Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal Company organized in 1920, natural gas was known to seep from the ground in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania.

“Natural Gas flowing from a hole near the back of the N. Philip Wheaton farm in Franklin township, seven miles from Montrose, has been used by the family for the past fifteen years for lighting and stoves,” noted a 1910 article in the Montrose Democrat.

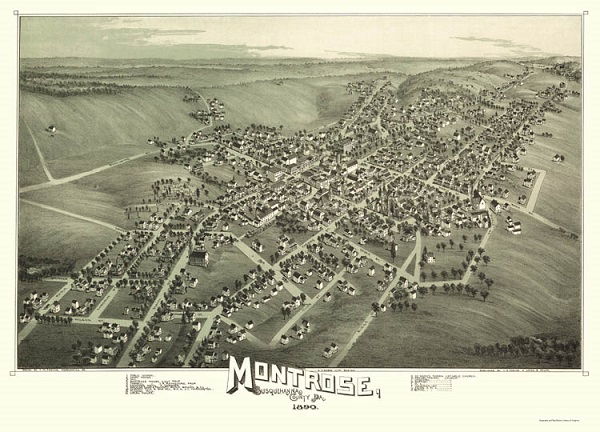

Montrose, established in 1812 in the northeastern corner of Pennsylvania near the New York border, was known for its quarry sites, which yielded a blue sandstone popular as an architectural and building stone.

An aero-view or “bird’s eye” map of Montrose, Pennsylvania, by Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler depicted this Susquehanna County community in 1890. The area’s quarries produced a durable blue sandstone today known as Pennsylvania Bluestone.

In late 1920, Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal launched plans to drill for natural gas to serve markets just to the north in Binghamton, New York, and to the south in Scranton. Capitalized at $300,000, the company offered investors shares for $10 each through an expansive newspaper campaign.

“One good gas well, yielding an average of 5,000,000 cubic feet a day would mean an annual yield of $565,750,” proclaimed advertisements in the Scranton Republican. Many readers remembered the economic boom from an earlier Pennsylvania natural gas field (see Natural Gas is King in Pittsburgh).

Before the end of 1921, Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal had sold enough common stock to finance drilling near Franklin Fork, a few miles from Montrose. The company’s cable-tool rig found natural gas at a depth of just 200 feet. Production records cannot be found.

The Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal Company natural gas well of 1921. Although the Pennsylvania company failed, today beneath Susquehanna County lies the Marcellus Shale with an estimated 500 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Photo courtesy of Susquehanna Historical Society, Horgan Collection.

“Many of the stockholders of the company residing in this immediate vicinity drove to the well as soon as the news was circulated in order to verify with their eyes what it seemed could hardly be true,” noted one contemporary account.

“A piece of tow (rope) was lighted and thrown down the ten-inch pipe, with the result that the lighted gas would flame up five feet in the air,” the report continued. “The flow has been steady ever since.”

Prospects for the company’s future looked good.

In April 1922, Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal stock still traded. As late as November, the company was considered viable and had plans to expand drilling operations in the field…if more funding could be secured.

However, the company soon disappeared from records. The Pennsylvania Internet Record Imaging System/Wells Information System, available online, may have further details.

Although the company drilled a successful natural gas well, newspaper advertisements to raise capital did not attract enough investors.

Today beneath Susquehanna County lies the Marcellus Shale with trillions cubic feet of natural gas, stretching through parts of New York State, Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

In 2012 alone Susquehanna County landowners received $300 million in lease royalties. Modern recovery techniques such as hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling have enabled extraction of this trapped gas.

But for Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal Company, such technology was years away. The company’s stock certificates may be valued by scripophily collectors for artistic and historical significance.

Cartographer Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler in 1890 published an aero view of Montrose – one of more than 400 Fowler panoramas, many depicting early oil boom towns, including an 1896 panorama of Titusville, Pennsylvania, where Edwin Drake launched the U.S. petroleum industry.

Learn more about oilfield artwork in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

_______________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Montrose Gas, Oil and Coal Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/the-dramatic-oil-company. Last Updated: April 13, 2022. Original Published Date: March 7, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

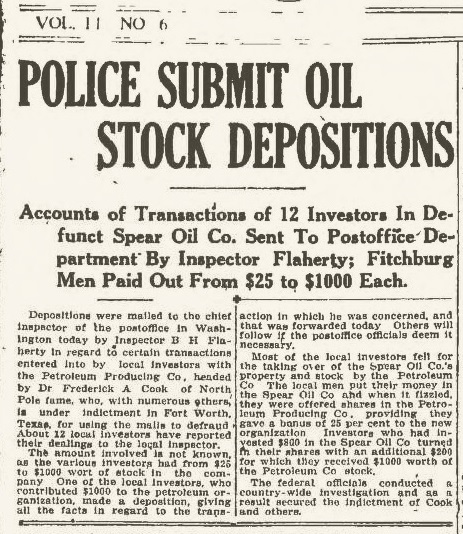

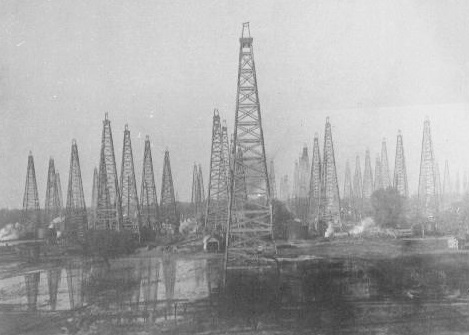

Speculators once again converged on a small town in Eastland County in 1918 as yet another West Texas drilling boom began with a gusher. Spear Oil Company soon joined them.

In September a well producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day had blown in near Desdemona, one of the first Texas towns established west of the Brazos River.

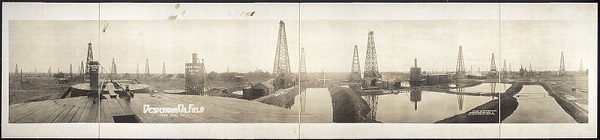

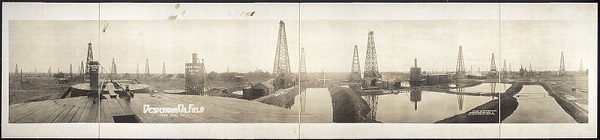

The Desdemona oilfield, Eastland County, Texas, circa 1919. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Desdemona had once been called Hog Town and Hog Creek Oil Company made the discovery (not a skilled conman’s Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company). Eastland County’s Ranger and Cisco communities experienced drilling booms the previous year.

The “Roaring Ranger” McClesky No. 1 well of October 1917 had reached a daily production of 1,700 barrels. Within two years eight refineries were open or under construction and Ranger banks had $5 million in deposits. ALso in North Texas, a 1918 gusher created boom town Burkburnett.

That oil field gained international fame for Ranger as the town that wiped out oil shortages during World War I, allowing the Allies to “float to victory on a wave of oil.” Eastland County’s Cisco would later gain fame as the crowded boom town Conrad Hilton visited after the war — and bought his first motel (see Oil Boom brings First Hilton Hotel).

Spear Oil Company

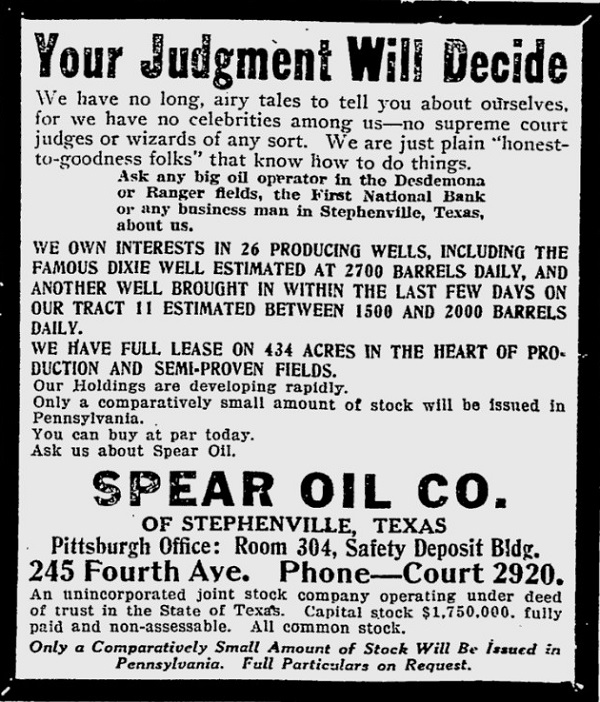

Spear Oil Company organized with capitalization of $1.75 million in 1919 — the same year the Desdemona field reached its peak annual production of almost 7.4 million barrels of oil.

With J.A. Spear as president and leases to drill in Desdemona, widespread promotion of stock sales was necessary to fund the of Stephensville, Texas, based new venture’s operations. But at least one oil stock promoter who had misrepresented the value of the region’s wells in 1914 was serving time in federal prison.

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

These new laws were designed to prevent the use of the U.S. Mail in stock promotion schemes. The South Carolina attorney general’s rejection excoriated the practice of “selling script or certificates of so-called ‘stock’ in the leasing and operation of what is claimed to be prospective development, producing and marketing of oil and gas in Texas.”

The trade publication United States Investor agreed. “We do not recommend Spear Oil as a purchase,” noted the magazine’s editors. “Apparently the people at the head of this company are much more at home selling stock than they are in operating an oil enterprise.”

Nonetheless, within a few months, a Wilmington newspaper published an “editorial” letter (no doubt paid for by the company) extolling Spear Oil Company properties.

Newspaper Ads and Editorials

“There are a number of wells being drilled on their royalties and several locations for wells on their solid leases,” the Wilmington Morning Star reported. “As a whole, we consider the securities of Spear Oil Company safe, with prospects for at least good, substantial dividends for many years and each of us has purchased a number of shares of their securities.”

The letter concluded: “In conclusion, we found the conditions and general outlook for the success of the company much better than we had expected, and even better than it had been represented to us. Respectfully submitted…”

Spear Oil did drill in Eastland County and complete oil wells. United States Investor was obliged to update and report net production of about 600 to 650 barrels per day from the company’s Desdemona operations in the southeast corner of Eastland County.

The company’s stock was still offered on the Fort Worth Exchange at $1.40 a share in September 1920, although it had not paid dividends and, “as yet and appears to be using its earnings for further development.” As far away as North Tonawanda, New York, promoters of Spear Oil wrote enthusiastic endorsements recommending the company’s stock.

Drilling a Well

In 1921, Spear Oil Company spudded its Blankenship No. 1 well, but soon shut it down and moved two strings of tools and three rigs to begin operations on another promising lease. The Blankenship No. 2 well’s progress was noted in oil trade publications.

“The Desdemona field now has approximately 315 completed wells that have a daily average production ranging from 4,000 to 6,000 barrels,” Oil Weekly reported on January 14, 1922.

“During the past week, the Spear Oil Company’s No. 2 Blankenship failed to show up as a producer after being shot with 20 quarts from 3,060 to 3,070 feet,” the publication added. “This well has a total depth of 3,085 feet, and is now being cleaned out.”

Learn more how a well was “shot” in Shooters – A Fracking History.

Meanwhile, the impact of over-drilling was clear as reservoir pressures and production from the field diminished. Spear Oil’s Blankenship No. 2 well failed along with many others and funding for continued operations could not be secured.

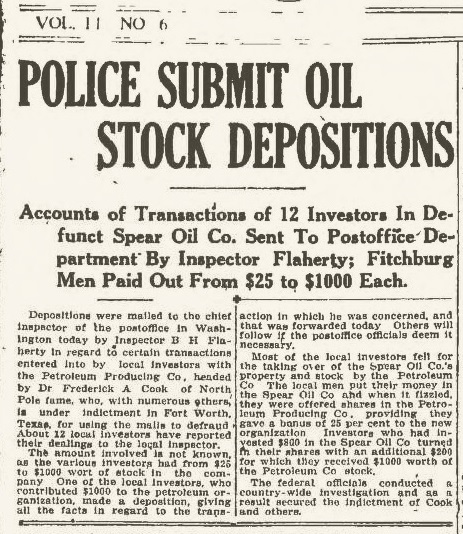

Stockholders of the failing Spear Oil Company were approached in 1923 by the famed (but fraudulent) North Pole explorer, Frederick Cook and his Petroleum Producers’ Association.

Cook’s stock manipulations and violations of blue sky laws ultimately landed him in prison, but not before many Spear Oil share owners were conned into exchanging their stock for Petroleum Producers’ Association while paying a 25 percent “bonus.”

Learn more about Cook in Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

Petroleum Producers’ Association stock was as worthless as Spear Oil Company’s, but investors were convinced otherwise, largely through the extraordinary promotional machinations of Seymour Cox. “Alphabet” Cox. The skilled huckster and others were convicted of ”dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from non-producing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

Another notable fraudster, J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth, created Pilgrim Oil Company and other shady oilfield ventures solely to bilk unwary investors.

It was not until 1934 that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was established to regulate the issue and sale of securities and to protect the public from increasingly clever stock promotions and manipulations. By then, Spear Oil Company was long gone. Its stock certificates may have value to scripophily collectors.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Spear Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: September 7, 2021. Original Published Date: February 1, 2014.

.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 10, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

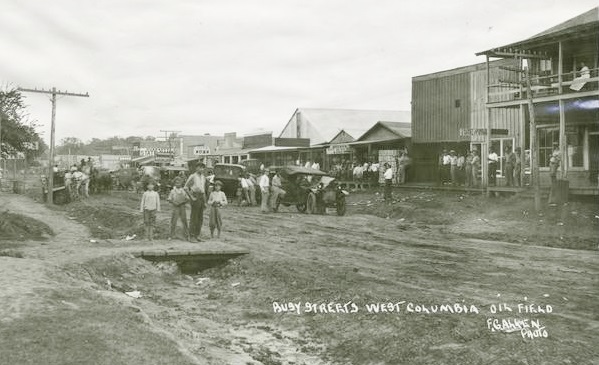

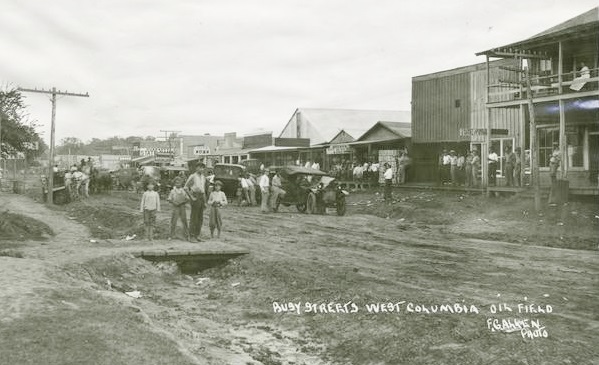

Lucky Jim Oil Company was created in March 1919 to pursue opportunities in the newly discovered West Columbia oilfield in Brazoria County, Texas (visit the Columbia Historical Museum in West Columbia to learn more about the first capital of the Republic of Texas).

The Brazoria County oilfield, 50 miles southwest of Houston, “was the youngest of the first rank salt dome oilfields of the Texas-Louisiana coastal region, and at present is the most productive of these fields,” reported the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) in 1921.

Wind knocked down the first derrick of a Lucky Jim Oil Company well drilled in 1919. The well reached 3,340 feet before the company gave up – and reorganized as the Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company.

Like many competing exploration companies formed during Texas drilling booms, Lucky Jim Oil Company did not survive its first dry hole. A Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company fared no better.

West Columbia field

Wildcatters had become interested in the West Columbia after oil discoveries on a lease owned by a former Texas governor. Gov. J.S. “Big Jim” Hogg first thought oil might be there and leased the land in 1901 (learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells).

When the Hogg No. 2 well was completed at 600 barrels of oil a day in January 1918, speculators rushed to lease nearby acreage. The 20-square-mile oilfield yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918.

The Hogg discovery wells led to a local boom that attracted inexperienced, even fraudulent, drilling companies that would not long survive. They planned to drill near property with proven oil production.

Advertisements appeared in Texas newspapers that included $10 per share stock promotions enticing investment in the West Columbia oilfield — with a promise to pay out 75 percent of any net earnings to shareholders. The ads assured investors of early dividends and admonished, “Buy Today, Tomorrow May Be Too Late.”

The Texas Company (later Texaco) was among companies that found success in the 20-square-mile oilfield in Brazoria County. The field yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918 alone.

Hedging against a dry hole and gambling on higher oil prices, Lucky Jim Oil declared in 1919, “We have immense holdings that we should be able to sell out on the present rise of prices in West Columbia, and pay our stockholders three or four for one on their investment without drilling a well.”

With funding from stock sales, the company was able to begin drilling its first well, the Brown No. 1, proclaiming it to be “within 1,800-feet of the Texas Company’s 20,000 barrel gusher.”

Drilling progressed for a few months until the derrick reportedly collapsed in high winds during a September storm. After rebuilding the wooden structure and resuming drilling, the well reached 3,340 feet. It was an expensive dry hole.

Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company

Within a month of the failed exploratory well, a reorganized Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company made its first appearance and tried again to secure funding to launch drilling operations in the crowded West Columbia oilfield.

A drilling boom resulted in the West Columbia oilfield reaching its annual peak production of 12.5 million barrels of oil a few years after its discovery.

The new company did not succeed in raising enough capital and soon disappeared, along with many other such “poor boy” operations in South Texas at the time. Only larger companies could absorb costs of a dry hole and continue drilling.

The Texas Company (later Texaco) – after drilling several dry holes in the West Columbia field – in July 1920 brought in the Abrams No. 1 well, which produced 26,500 barrels a day for six weeks (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

By 1921, the West Columbia field reached its peak annual production of 12.5 million barrels of oil — but by then the Lucky Jim Oil Company and Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company were both history.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lucky Jim Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/lucky-jim-oil-company. Last Updated: September 4, 2021. Original Published Date: September 8, 2015.

.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”

With oil stock promotions appearing in newspapers nationwide, states began taking action. In August 1919, the attorney general of South Carolina refused Spear Oil Company’s request to sell stock in his state because the company failed to comply with South Carolina “Blue Sky Laws.”