by Bruce Wells | Oct 24, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

New companies rush to drill at Spindletop Hill in early 1900s.

When a geyser of oil erupted in 1901 on Spindletop Hill, near Beaumont, Texas, it launched the greatest oil boom in America — far exceeding the nation’s first commercial oil well in 1859.

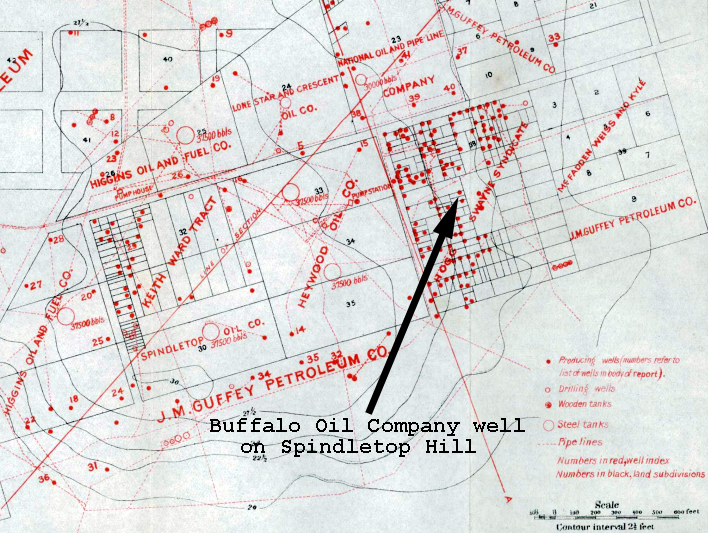

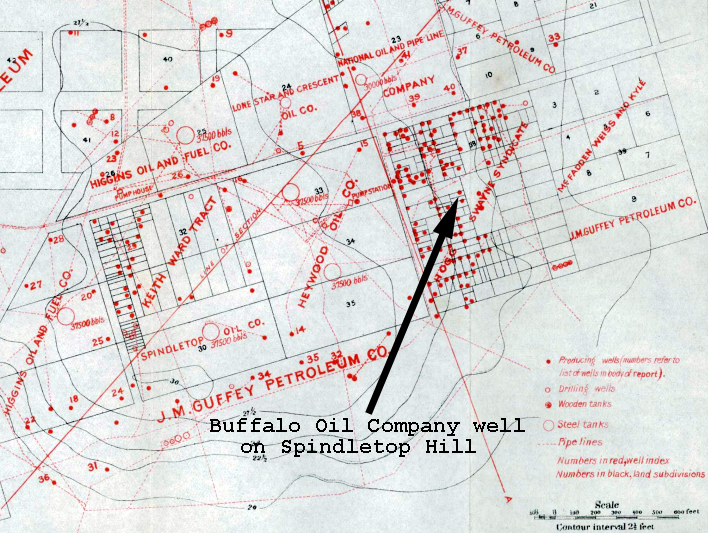

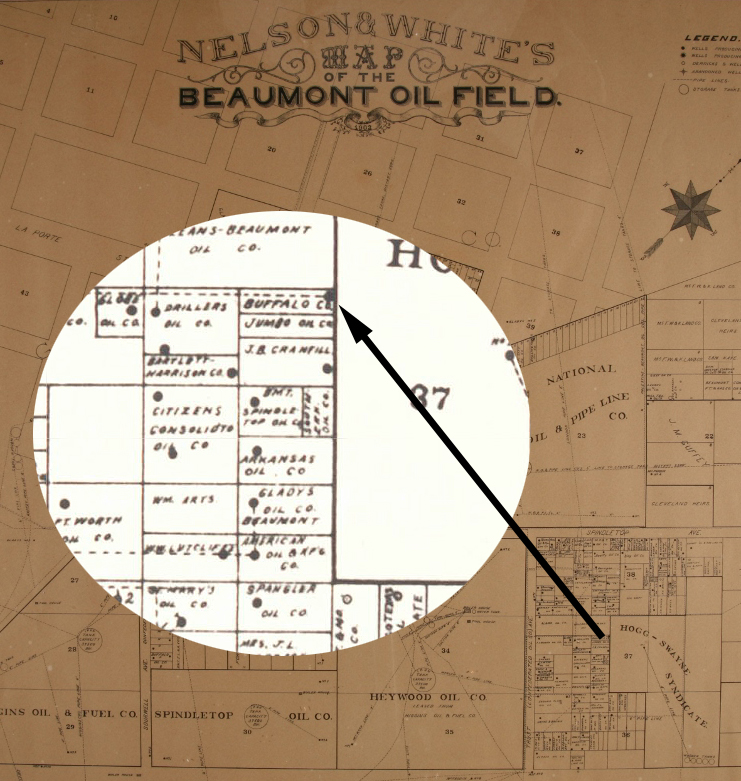

Many new and inexperienced oil ventures were formed almost overnight, including Buffalo Oil Company. The Spindletop field produced 43 million barrels of oil in its first four years, helping to launch the modern petroleum industry.

Among the 280 wells at Spindletop in 1902, Buffalo Oil completed a producing oil well at a depth of 960 feet on a lease of only 1/32 of an acre.

Buffalo Oil Company had quickly formed with $300,000 capitalization and stock listed with par value of 10 cents. Encouraged by the first well’s success, speculators invested in the company’s second. But by May 1902 the second Buffalo Oil well was “dry and abandoned” after reaching 1,400 feet deep.

As at least one expert noted at the time, the average life of flowing wells was short, “frequently but a few weeks and rarely more than a few months, with constantly diminishing output.”

Meanwhile, competing companies drove up the cost of drilling equipment and leases. Spindletop Hill was crowded with wooden derricks, oil storage tanks, and roughnecks.

Batson Oiflield

With signs of Spindletop production dropping, Buffalo Oil shifted operations to nearby Batson, where a 1903 well drilled by W.L. Douglas’ Paraffine Oil Company produced 600 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 790 feet. But the exploration company’s luck did not improve.

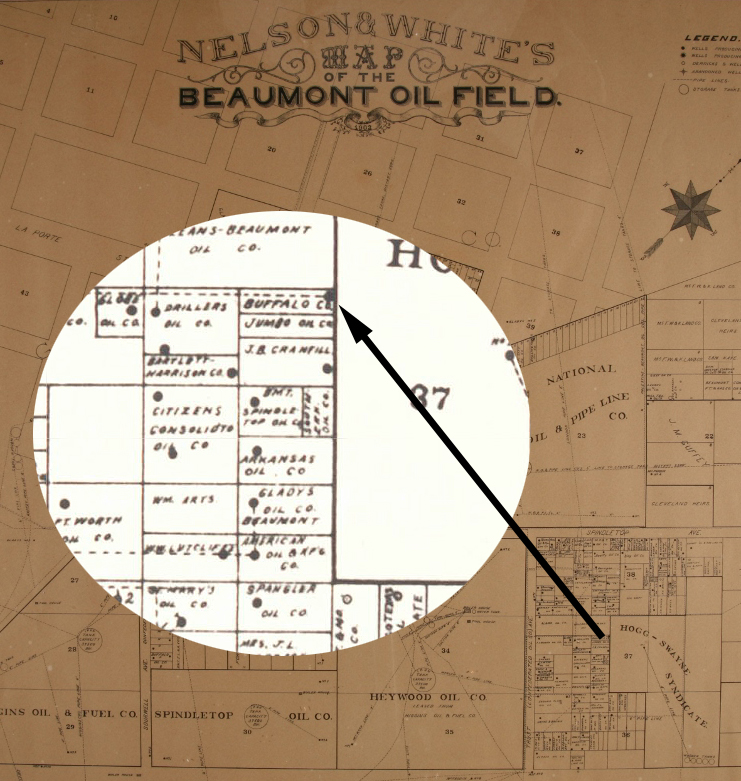

Map with detail showing Buffalo Oil Company lease among other drilling companies at Beaumont, Texas, home of a giant oilfield discovered in 1901.

As the Batson field reached its peak monthly production of 2.6 million barrels of oil, a fire swept through the crowded oilfield.

“The fire burned furiously for several hours and though there were no fire appliances on the field, it is doubtless if equipment could have been used owing to the intense heat generated by the flames,” noted the Petroleum Review and Mining News.

Buffalo Oil Company’s well, derrick and equipment were completely destroyed.

Often caused by lightening strikes, oil tank fires were sometimes fought using cannons (learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires). After the Batson fire, the annual Buffalo Oil Company stockholder’s meeting took place in April 1904.

Fire engulfed the Batson oilfield in 1902, destroying the equipment and future of Buffalo Oil Company. Photo courtesy Traces of Texas.

“The company states that their recent investment at Batson so far has proved a serious loss to them, and the present outlook is very unfavorable,” reported the Petroleum Review and Mining News. But it got even worse.

Two weeks after the dire report to share owners, a second Batson fire destroyed another Buffalo Oil producing well and two 1,200-barrel storage tanks. Petroleum Review and Mining News concluded the fire “probably originated through an explosion in the pumping plant.”

The Batson oilfield would continue to produce for many years, but without Buffalo Oil Company. As late as 1993 the field yielded almost 200 barrels of oil a day, but Buffalo Oil was history without having paid a dividend.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Buffalo Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/buffalo-oil-company. Last Updated: October 31, 2023. Original Published Date: October 28, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 25, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

Although William S. Pratt entered the oil exploration business in Wyoming in 1915, he soon moved to Kansas and organized the Wichita Eagle Oil Company. It and many newly formed “wildcatting” companies would not succeed in risky Mid-Continent drilling and production (see Otter Creek Oil & Gas, formed by Wichita businessmen and the Cahege Oil & Gas Company, at Caney, where a Kansas gas well fire had made headlines.

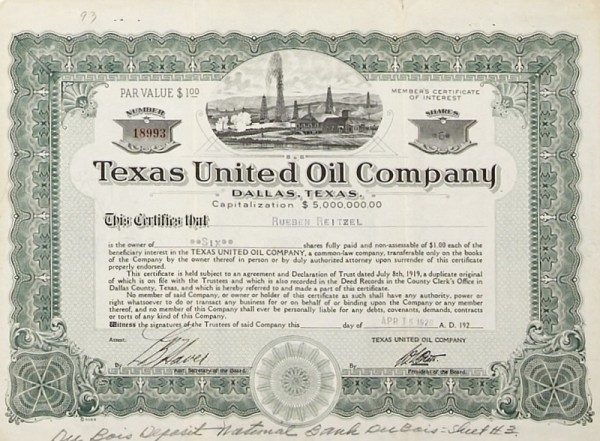

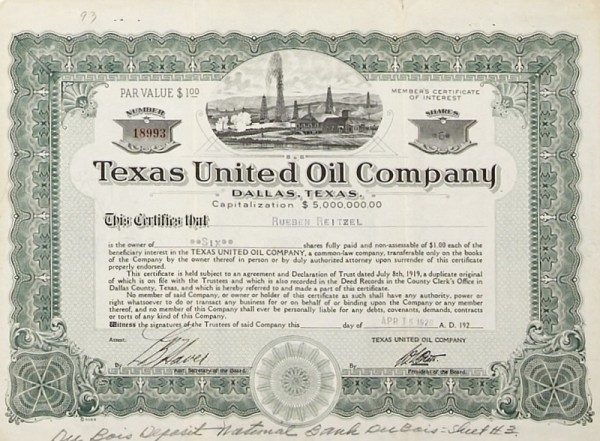

A major oilfield discovery in North Texas — “Roaring Ranger” — in 1917 also attracted national attention. Pratt launched his Texas United Oil Company there in July 1919. By the last quarter of 1919, the Texas comptroller’s office reported Pratt’s company had produced more than 31,000 barrels of oil.

Promoting Texas United Oil

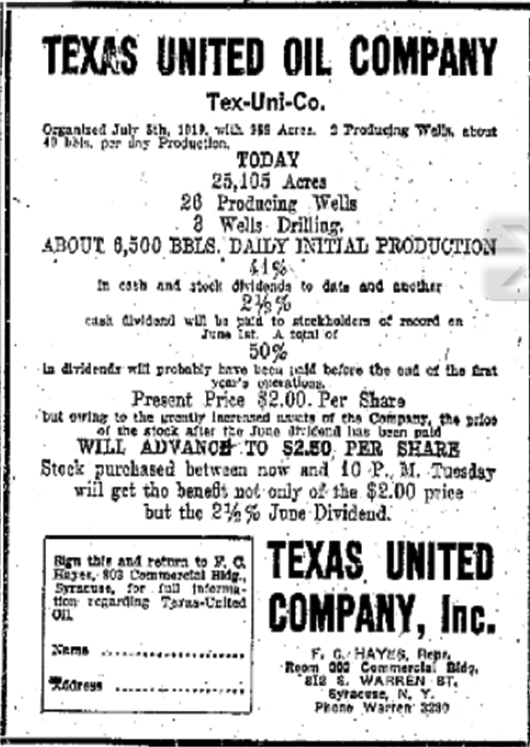

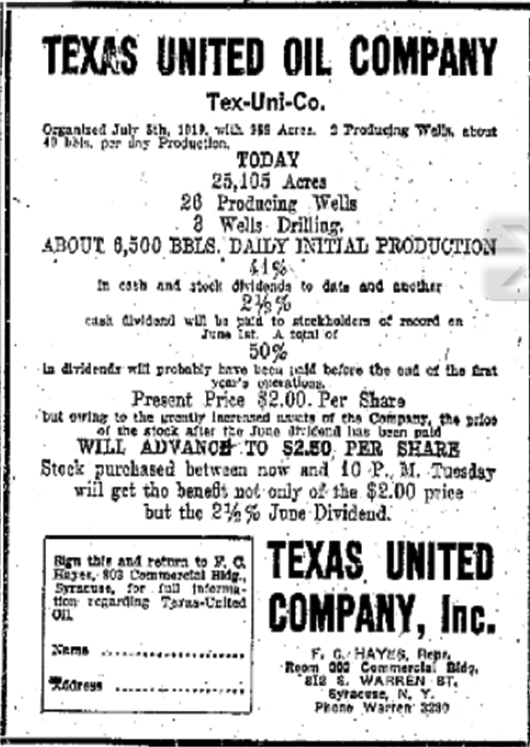

Texas United Oil Company solicited investment capital with a series of ads placed in newspapers nationwide, including in Spokane, Washington; El Paso, Texas; Troy, Syracuse, and Plattsburgh, New York; and Washington D.C.

From December 1919 through 1920, company marketing efforts promised: For Quick Returns and Unlimited Profits Invest With the Texas United Oil Company…27 Wells Showing Initial Production of 8,700 Bbls. Daily.

But at least one investment magazine described the company as unlikely to prosper, and the assessment proved to be accurate.

By December 1920, Texas United Oil Company entered into receivership and did not emerge until April 27, 1921, reorganized and with a new president, Aldred S. Wright of Philadelphia.

Despite the reorganization, the company did not survive long. United States Investor reported in 1922 that Texas United Oil Company had very little value.

“It is of course not listed on any of the principal exchanges,” the magazine noted, adding that no dividends had been issued since 1920. “The company had about $1,300,000 stock outstanding and there was one public offering by people in Hartford, Connecticut, at $2 per share. Two cents per share is approximately the price now.”

“A Sure and Safe Investment ”

October 1, 1919 – The Texas United Oil Company of Dallas produces 31,541 barrels of oil valued at $10,789 between October 1 and December 31, 1919, according to the Texas comptroller.

December 21, 1919 – In one of its first newspaper appearances, President W. S. Pratt describes the company’s leases and production success in the Northwest Extension of the Burkburnett oilfield.

Pratt announces that the company’s trustees have resolved to increase capital to $5 million and he encourages potential investors to purchase stock at $2 per share to enable “development of our many properties and the purchase of additional production.” — ad in Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington

January 3, 1920 – The company is promoted in an open letter advertisement sent from Electra, Texas, “to our stockholders and others” from J. R. Lucore, shareowner, of Olean, New York. Lucore reports very positive on-scene observations of drilling and production in progress. His endorsement follows:

“The Texas United is a sure and safe investment for anyone to buy stock in. No one need be in the least afraid to invest as large as one see fit and his investment will be the safest and surest of any company operating in the State…I expect to arrive home in a few days and will enlarge my stock order to you in the Texas United Oil Company on my arrival.” — ad in Gloversville, N.Y., Morning Herald

January 31, 1920 – The company is reported as formed by a Declaration of Trust filed on July 2, 1919, with trustees L. W. Harrington, Herbert Bingham, H. C. Ralph and J. M. Davis. It receives a poor recommendation:

January 31, 1920 – The company is reported as formed by a Declaration of Trust filed on July 2, 1919, with trustees L. W. Harrington, Herbert Bingham, H. C. Ralph and J. M. Davis. It receives a poor recommendation:

“Our information as to the management is that it is not as economical as it might be, and that operating costs are likely to be altogether too high because of rather poor judgment in planning the work.” — article in United States Investor

“The King of the Oil Companies”

February 21, 1920 – The Texas United Oil Company of 1209 Half Main Street, Dallas, Texas, asserts that the United States Investor’s bad recommendation refers to another company of the same name whose headquarters is in Wichita and not Dallas. The company protests that “conclusions relative to the Wichita enterprise cannot fairly be applied.” Investigation planned. — article in United States Investor

February 25, 1920 – The company proclaims itself as “The King of the Oil Companies” and promises 30 percent dividends and $5 million in capital stock with 12 producing wells. — ad in Spokesman Review, Spokane, Washington

March 13, 1920 – Company promotion continues, citing “12 producing oil wells – over 3,000 barrels daily” and “30 percent dividends have been paid in 7 months” Shares are offered at $2. Agent is J. S. Miramon, Rensselaer Hotel, Troy “Salesmen wanted: Liberal commission. Phone for appointment.” — ad in Troy (N. Y.) Times

April 17, 1920 – J. S. Miramon, now of Barows Company, 141 Broadway, New York City, advertises “Wise Investors, Increase your income” with company’s “2 percent monthly dividends, with record of 39 percent in dividends past nine months.” — ad in El Paso (Texas) Herald

April 10, 1920 – Analysts confirm poor recommendation after consulting with the company, the New York City based owners of the company. “We cannot do otherwise than classify this as the ordinary type of oil gamble, a quite unproven enterprise, depending for its future upon the skill with which it is managed. — article in United States Investor

May 15, 1920 – Tex-Uni-Co. (trademark for Texas United Oil Company) advertises 18 producing wells, two ready to come in per April 30 telegram testimonial by Ralph P Reed, president National Investors Protective Corporation.

“These dividends will make a total of 43 ½ percent in cash and stock dividends paid in less than one year.” A. E. Roberts and Co., Washington, D.C. — ad in The Federal Employee, Washington D.C.

May 30, 1920 – The company promotes its self (Tex-Uni-Co.) as having rapidly grown from its origins in July, 1919 with 389 acres and two 2 producing wells, yielding about 42 barrels a day of production grown until. — ad in Syracuse Herald, Syracuse, New York.-

“Quick Returns and Unlimited Profits”

Jun 2, 1920 – “For Quick Returns and Unlimited Profits Invest With The Texas United Oil Company” upstate New York advertisement proclaims “27 Wells Showing Initial Production of 8,700 BBls. Daily.” — ad in Daily Republican, Plattsburgh, New York

December 1920 – Company enters into receivership.

February 25, 1921 – Advertising continues for twelve producing wells 30 percent dividends.” — ad in Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington

April 16, 1921 – Value of the company plummets as it is reported to have “been the subject of much litigation of late…Texas United shares have declined to around five cents since their first appearance upon the market at $2 per share.” — article in United States Investor

April 27, 1921 – The company emerges from receivership reorganized and with a new president, Aldred S. Wright of Philadelphia.

November 11, 1922 – The company “is of little value …two cents per share is approximately the price now.” — article in United States Investor

More history ablur U.S. petroleum exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

Among trusted financial publications — and available at many libraries — is the Directory of Active Stocks and Obsolete Securities published by Financial Information, Inc., Jersey City, New Jersey.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Texas United Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/texas-united-oil-company. Last Updated: October 1, 2023. Original Published Date: January 5, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 11, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

A Nevada independent oil company made headlines just one month after it was formed in 1960. It would not bode well for Henderson and Las Vegas investors.

“Geologist Claims There’s Oil At Foot Of Black Mt.,” the Henderson Home News proclaimed in its February 4, 1960, edition. “Starts Drilling Operations Tomorrow,” the headline continued.

The Nevada newspaper quoted the newly formed Trans-World Oil Company and on-site petroleum expert A.J. (Arthur James) Bandy. The consulting geologist also owned Petroleum Engineering Company of Bakersfield, California, home to prolific Kern County oilfields.

The Henderson, Nevada, newspaper added to the public’s oil fever with February 1960 headlines like “Well! Well! Well! City Might Try For Another.”

As Trans-World Oil began exploring for petroleum at Henderson, A.J. Bandy educated newspaper readers about geology.

“The oil found here is a gift of the sea, formed by deposits of marine mollusks and mammals, and still later by the hulks of enormous Saurians which stomped the earth in the Permian era,” Bandy proclaimed. His enthusiasm would prove misinformed.

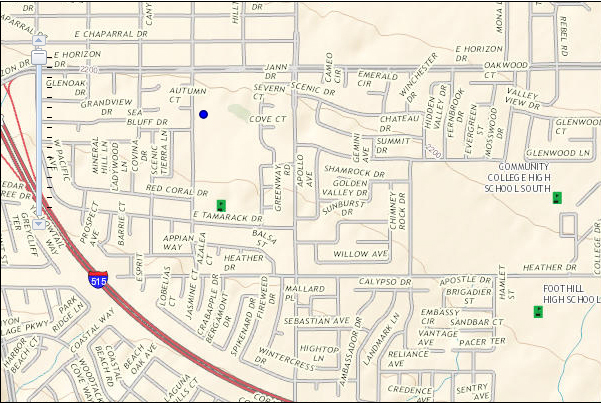

Company officers J.K. Houssels, Leonard Wilson and Bill Boyd had leased 5,000 acres southeast of Las Vegas. They chose a drilling site in what later became O’Callaghan Park in Henderson.

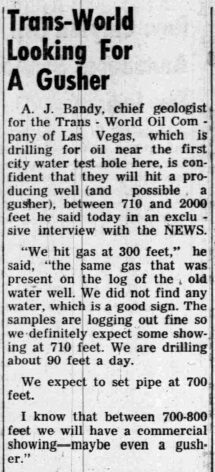

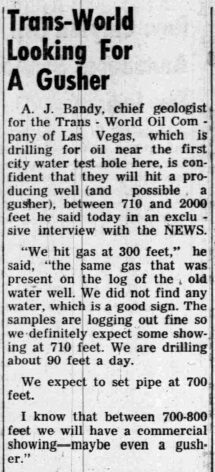

As nearby drilling continued in 1960, the Henderson newspaper quoted enthusiastic reports form the company geologist.

With drilling of the Houssels-Wilson-Milka No. 1 well beginning on February 4, 1960, the Henderson Home News began periodic updates for its readership — which included potential investors in Trans-World Oil Company.

Making Hole

After a month of drilling with an obsolete cable-tool rig to reach 300 feet, the consulting geologist urged going deeper.

“I know that between seven hundred and eight hundred feet we will have a commercial showing – maybe even a gusher,” Bandy declared of the Clark County wildcat well. By March there indeed were intermittent showings of oil and natural gas.

“We’ve struck oil!” A.J. Bandy proclaimed on April 4, telling the Henderson Home News that he had drilled into commercial quality oil strata at 1,312 feet.

“Henderson will have oil wells all over the place – there’s oil under the whole town,” the front page exulted. Bandy further explained that drilling had been stopped so an electric log could be run the next day.

“If you don’t believe it, go cut yourself a slice of sand up there which has been taken from the hole,” Bandy said. “Put the sand in a bottle and put ether in it. Then shake it. Oil will come out of it.”

However, at least one local oilman was skeptical. “I’ll drink every gallon of oil that’s found here,” said Mark Leff, who reportedly “laughed off any possibility of such a find.”

Despite Leff’s doubts, “several Las Vegas people” invested in geologist Bandy and Trans-World Oil, which continued to drill until July 1960. There were no more showings of oil or natural gas, no Henderson oilfield.

When the total depth reached 2,155 feet, the company suspended drilling.

People vs. Bandy

The well remained idle for two years as Trans-World Oil’s fate became increasingly obscure — and “consulting geologist” Bandy discovered problems of his own. On August 9, 1961, a California court convicted A.J. Bandy of check fraud.

Court documents report that Petroleum Engineering Company was “a fictitious firm name adopted by defendant Bandy” and that the company’s address “was a telephone answering service.”

Bandy’s deceptive business checks were “a specially printed form containing a picture of a gushing oil well.” His final appeal was denied on May 21, 1963. People vs. Bandy documents note the defendant’s credibility was impeached by three prior convictions dating back to 1942, including one for federal criminal conspiracy. He ended up in San Quentin.

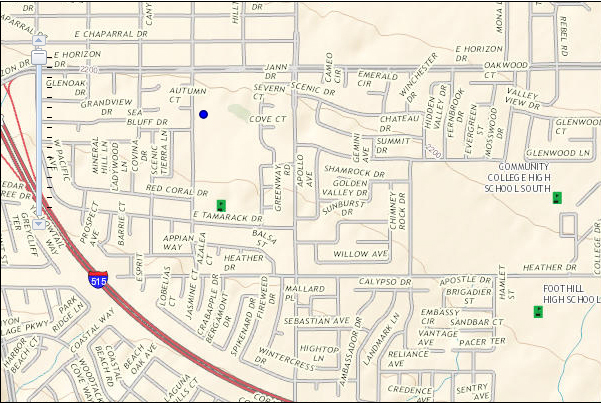

A map of Henderson, Nevada, today a Las Vegas suburb. The blue dot is the 1960 drilling site of the Tans-World Oil Company exploratory well north of O’Callaghan Park. Map courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

Former Trans-World Oil company officer Leonard Wilson took one last gamble on the Houssels-Wilson-Milka No. 1 well. In March 1962, he returned to the site and drilled another 145 feet over the next five months. The added depth still found no commercial quantities of petroleum.

Admitting defeat on August 6, 1962, Wilson plugged and abandoned the once headline-making well.

The last business days and fate of Trans-World Oil Company have been lost. The Henderson Home News quit reporting on the Nevada oil patch venture. The newspaper ceased publication in 2010 after being acquired by the Las Vegas Sun.

First Nevada Oil Well

On February 12, 1954, after decades of noncommercial wells — the first drilled 1,890 feet deep near Reno in 1907 — Nevada became an oil producing state.

Shell Oil Company’s second test of its Eagle Springs No. 1 well found oil in Railroad Valley, Nye County. The well, 260 miles north of Trans-World Oil’s attempt, revealed Nevada’s first oilfield, according to the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology.

The discovery well produced oil from a productive interval between 6,450 and 6,730 feet deep. About a dozen wells in the Eagle Springs oilfield produce 3.8 million barrels by 1987.

Learn more in First Nevada Oil Well.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Roadside Geology of Nevada (2017). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2017). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2023 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Trans-World Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/trans-world-oil-company. Last Updated: April 15, 2023. Original Published Date: May 15, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 1, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

A wildcat well struck oil in 1930 and pumped it for decades from the city dump of Hermosa Beach, California.

As the Great Depression began, California-Ventura Oil Company discovered the Hermosa Beach oilfield. The newly revealed field proved to be a key addition to the prolific Torrance oilfield, discovered a decade earlier. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Apr 1, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

High hopes for oil riches from someone’s family heirloom.

Despite years of mergers and acquisitions, the 1924 Palmer Union Oil Company stock certificate Tony Marohn bought at a garage sale did not make him a millionaire. As with most obsolete securities, no ownership in the company or its successors remained by the time it became part of Coca-Cola.

For many people like Marohn, discovering an old stock certificate brings hopes of wealth. This seems especially true if the certificate is one of the thousands of petroleum companies incorporated since the first, the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York, organized in 1855.

Unfortunately, as the research posted in Is My Oil Oil Stock worth Anything? shows, the highly competitive, boom-and-bust world of oil and natural gas exploration leaves many casualties. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

Elk Basin United Oil Company incorporated in 1917 seeking oil riches in Wyoming’s booming Elk Basin oilfield. Oilfields found in North Texas, including a 1911 gusher at Electra, already had resulted in a rush of new exploration ventures – and created boom towns like Burkburnett.

Wherever found, America’s newly discovered oilfields led to the founding of many exploration ventures that competed against more established companies.

Newly formed companies frequently struggled to survive as competition for financing, leases, and drilling equipment intensified, especially as exploration moved westward.

Wyoming Oilfields

In a remote, scenic valley on the border of Wyoming and Montana, a discovery well opened Wyoming’s Elk Basin oilfield on October 8, 1915. Wyoming’s earliest oil wells had produced quality, easily refined oil as early as 1890.

Drilled by the Midwest Refining Company, the wildcat well produced up to 150 barrels of oil a day of a high-grade, “light oil.” Credit for oil discovery is given to geologist George Ketchum, who first recognized the Elk Basin as a likely source of oil.

“Gusher coming in, south rim of the Elk Basin Field, 1917.” Photo courtesy American Heritage Center.Ketchum, a farmer from Cowly, Wyoming, in 1906 had explored the area with C.A. Fisher, who had been the first geologist to map a region within the Bighorn Basin southeast of Cody, Wyoming, where oil seeps were discovered in 1883.

The Elk Basin, which extends from Carbon County, Montana, into northeastern Park County, Wyoming, attracted further exploration after the 1915 well. More successful wells followed.

Once again, petroleum discoveries in unproved territory attracted speculators, investors, and new companies – including the Elk Basin United Oil Company.

Established petroleum companies like Midwest Refining — and the Ohio Oil Company, which would become Marathon Oil — came to the Elk Basin. These oil companies had the financial resources to survive a run of dry holes or other exploration hazards.

The exploration industry’s many smaller and under-capitalized companies would prove especially vulnerable.

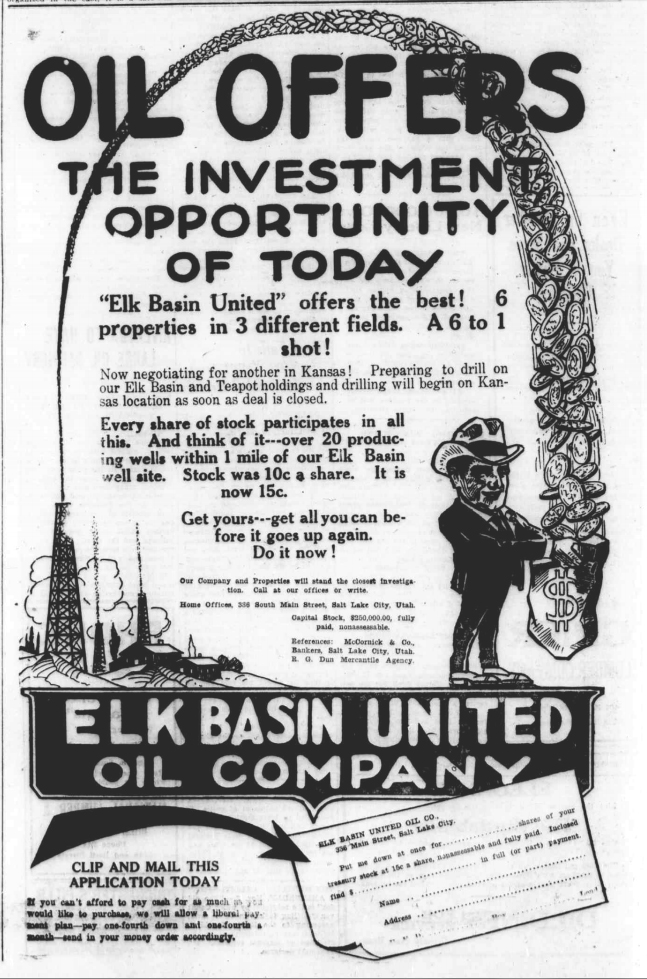

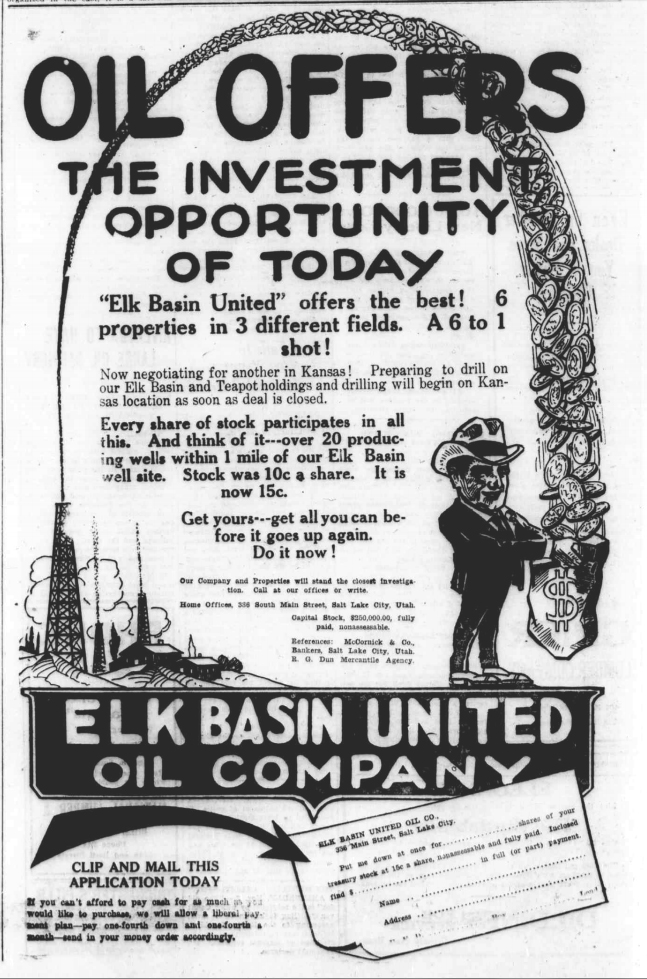

Audacious advertising claims helped Elk Basin United Oil Company compete for investors.

Is My Old Oil Stock Worth Anything features several such small players in Wyoming’s petroleum history, including the notorious Dr. Frederick Albert Cook (Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter). Even Wyoming’s famous showman, Col. William F. Cody, got caught up in the state’s oil fever (Buffalo Bill Shoshone Oil Company).

Elk Basin United Oil Company

Elk Basin United Oil Company of Salt Lake City, Utah, incorporated on July 30, 1917, and acquired a lease of 120 acres in Wyoming’s Elk Basin oilfield. By February 1918, company stock sold for 12 cents a share.

Enthusiastic newspaper ads promoted its “6 properties in 3 different fields…A 6 to 1 shot!” Twenty producing wells were reputed to be within one mile of Elk Basin United Oil’s Wyoming well site.

Meanwhile, Elk Basin United Oil reported expansion plans underway in a growing Kansas Mid-Continent oilfield. The company secured leases near Garnett and completed four producing oil wells, yielding a total of about 500 barrels of oil a month. It added an additional 112 acres and planned a fifth well.

Prairie Pipe Line Company (later Sinclair Consolidated) completed pipelines into the Garnett field through which several companies looked to transport their oil production.

However, growing competition from better funded exploration ventures and low crude oil prices ranging between $1.10 and $1.98 per barrel of oil in 1917 and 1918 drove many small companies into consolidations, mergers or bankruptcy.

Elk Basin United Oil, exploring back in Wyoming by March 1919, sought a lease on the property of the First Ward Pasture Company bordering the Utah line, “with a view of prospecting the property declare the surface showing to be very favorable for an oil deposit.” But financial issues continued to burden the company.

In December 1919, Oil Distribution News reported Basin United Oil Company was negotiating mergers with the Anderson Oil Company and the Kansas-United Oil Company, with a proposed capitalization of $1 million. With no results of the planned combination documented, Elk Basin United Oil Company disappeared from financial records soon thereafter.

_______________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Elk Basin United Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/elk-basin-united-oil-company. Last Updated: September 29, 2022. Original Published Date: October 1, 2021.

(2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

January 31, 1920 – The company is reported as formed by a Declaration of Trust filed on July 2, 1919, with trustees L. W. Harrington, Herbert Bingham, H. C. Ralph and J. M. Davis. It receives a poor recommendation:

January 31, 1920 – The company is reported as formed by a Declaration of Trust filed on July 2, 1919, with trustees L. W. Harrington, Herbert Bingham, H. C. Ralph and J. M. Davis. It receives a poor recommendation: