by Bruce Wells | Dec 11, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

Texas Oil boom brings shady searchers for petroleum riches.

It was the greatest petroleum exploration and production since the birth of the U.S. oil industry in 1859. Hundreds of new companies formed in the wake of the spectacular 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, Texas. Few had experience in the highly competitive and risky business of exploring for oil.

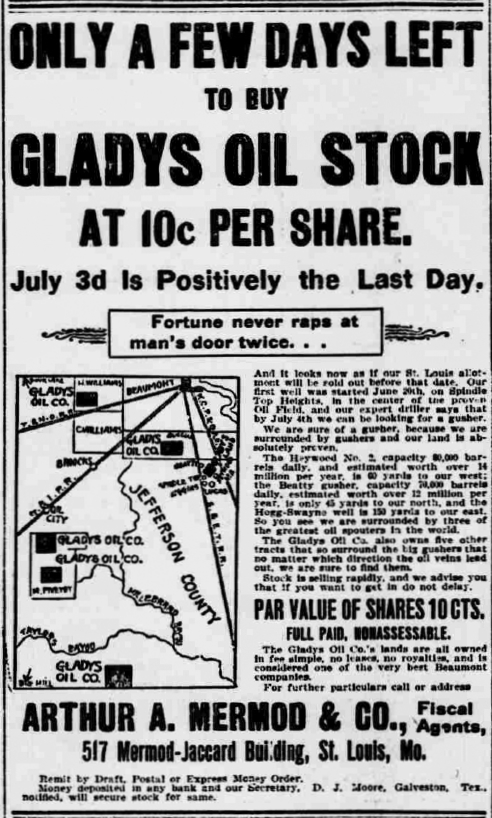

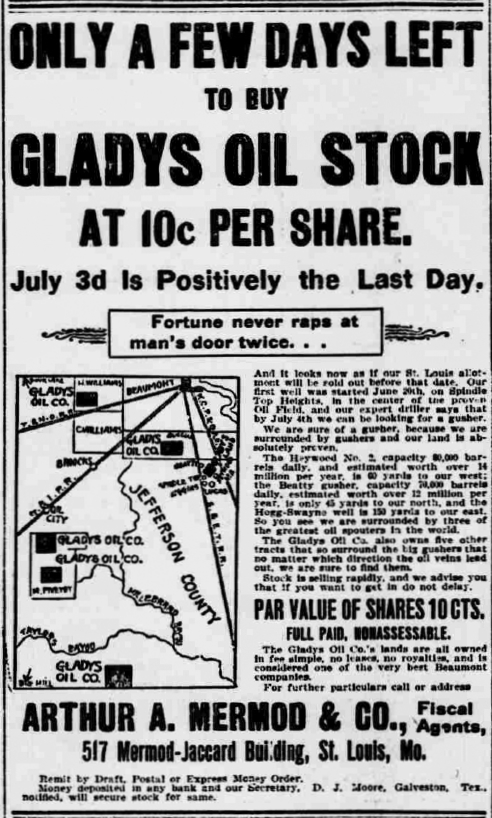

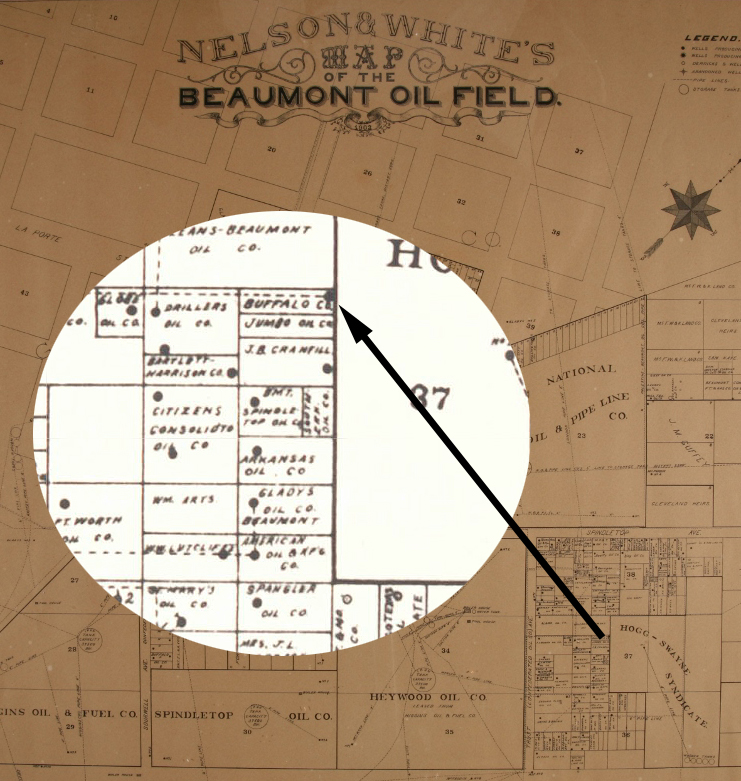

Among those ready to make fortunes for investors were two new “Gladys Oil” companies. One was from Beaumont, the other from Galveston. Contemporary maps show the Gladys Oil Company of Beaumont to have drilled a successful well very close to the famous January 10, 1901, “Lucas Gusher” well at Spindletop Hill that launched the modern U.S. petroleum industry.

Also in 1901, after 29 days of drilling in block 37, the company reported production from “Gusher No. 67” at a depth of 1,025 feet. Locating the “black gold” did not necessarily promise success.

“Swindletop”

By 1903 the Texas Secretary of State reported that Gladys Oil Company of Beaumont had “forfeited its right to do business in the state of Texas” due to a failure to pay franchise taxes. In a scenario that would repeat itself in other oilfields in coming decades, production from the giant field soon brought a collapse in oil prices.

By January 1902, stocks of both Gladys Oil companies were trading for less than 10 cents a share. The company was sued, lost, and United States Investor magazine reported it to be worthless two years later. Meanwhile, because some cash-strapped and desperate companies made questionable claims, newspapers began referring to the historic 1901 discovery as “Swindletop.”

In 1907, Success Magazine named the company in its “Fools and their Money” expose of fraudulent promotion schemes perpetrated by the New York, Chicago, and Beaumont Security Oil Trust. The Gladys Oil Company of Galveston lasted a little longer than its Beaumont twin, but not without controversy.

The trust had proclaimed, “it was impossible to lose” with an investment Gladys Oil Company of Galveston. In 1911 R.M. Smythe’s, Obsolete American Securities and Corporations, reported the stock to be worthless. Read about Pattillo Higgins, the man behind the great Spindletop discovery — and his Gladys City Oil, Gas & Manufacturing Company — see Prophet of Spindletop.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Gladys Oil Company — Oil Shale Pioneer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/gladys-oil-company. Last Updated: December 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 11, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 4, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

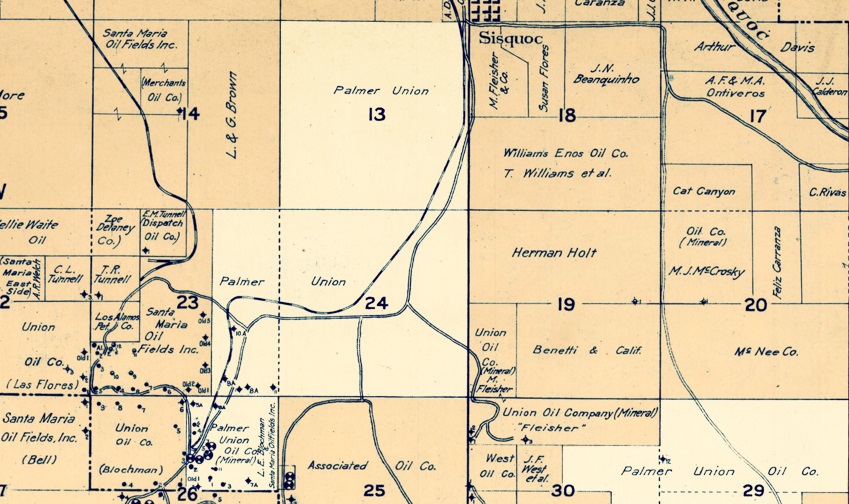

Oilfield discovery in 1908 at Cat Canyon, California, began company’s lengthy corporate convolution.

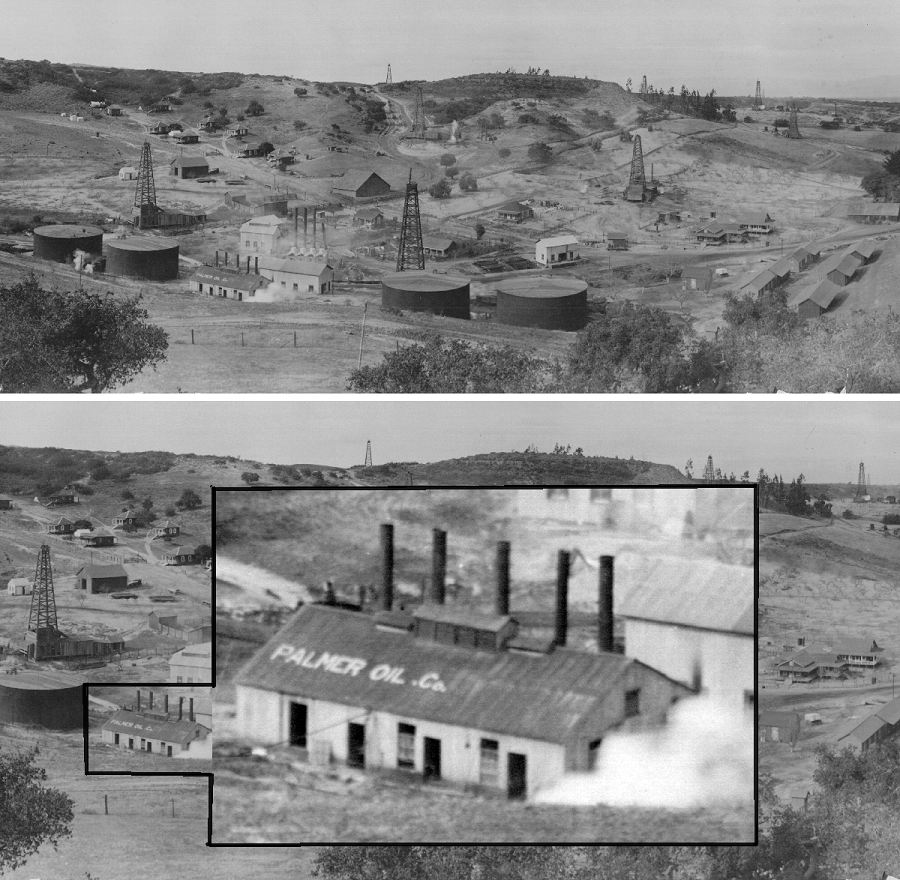

In the Solomon Hills of central Santa Barbara County, California, the search for oil and natural gas began in 1904 at Cat Canyon. Exploration companies unsuccessfully drilled there for four years before Palmer Oil Company discovered an oilfield about 10 miles southeast of Santa Maria.

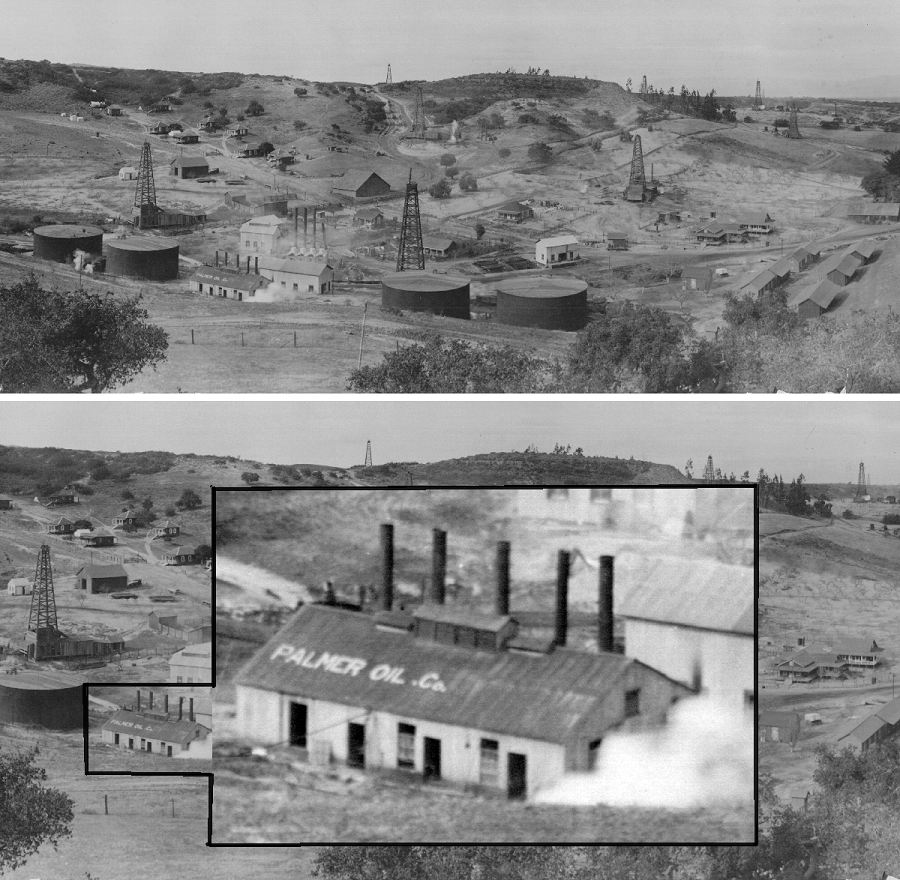

Palmer Oil Company derricks and refinery in Santa Barbara County, California, circa 1920s.

Palmer Oil’s Santa Maria well initially produced 150 barrels of oil a day, but within a few months it jumped to 10,000 barrels a day. The company completed a second well that also proved to be a true gusher. With it and other 1908 discoveries, Palmer Oil opened the Cat Canyon oilfield — the largest in Santa Barbara County at the time.

“The Palmer Oil Company is generally concluded to have opened one of the biggest and richest oil fields in California by the bringing in of its two gushers in the Cat Canyon District, now doing 10,000 barrels per day between them,” declared the trade publication “Oil Age Weekly” on September 9, 1910.

Although the Cat Canyon oilfield produced “heavy oil” with a high sulfur content, the success of Palmer Oil brought new investors, and the company was capitalized at $10 million by the beginning of 1911. The latest oil boom (see First California Oil Wells) attracted 26 exploration companies that completed 35 producing wells.

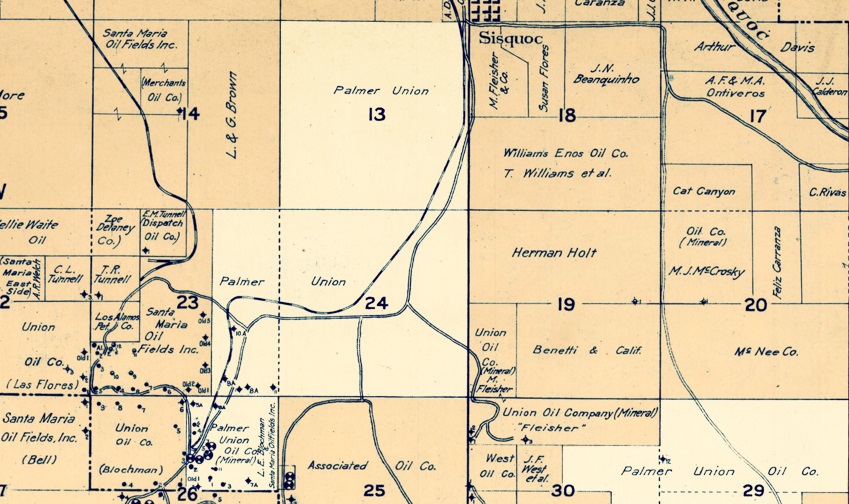

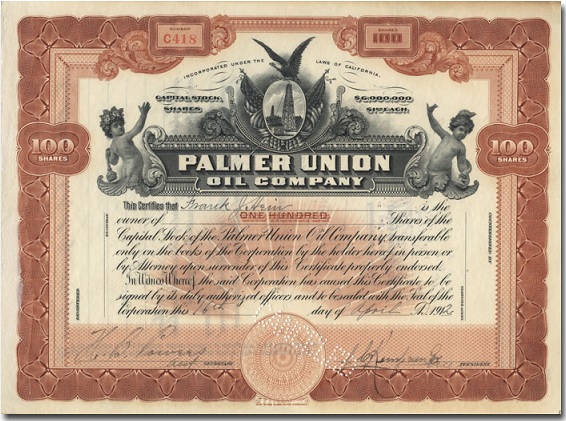

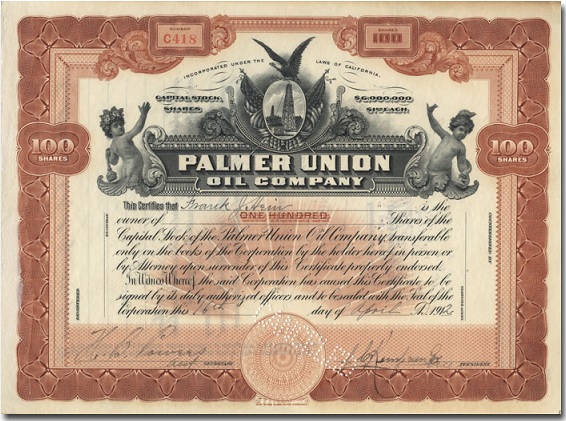

By 1927, Palmer Oil Company had reorganized into Palmer Union Oil Company as it continued to drill on Santa Barbara, California, leases.

By 1927, despite Cat Canyon’s proven oil reserves, drilling and production challenges of the heavy, high sulfur content prompted investors to look for better returns on their investments.

Palmer Oil to Coca-Cola

New drilling in Cat Canyon stalled — as did Palmer Oil, which began the first of its many corporate convolutions by becoming the Palmer Union Oil Company.

In January 1932, Palmer Union Oil became Palmer Stendel Oil Corporation, beginning decades of mergers and acquisitions: Palmer Stendel Oil Company – Petrocarbon Chemicals Incorporated – Great Western Producers – Pleasant Valley Wine Company – Taylor Wine Company – Coca-Cola Company.

After the Great Depression and World War II, water-flooding technology resurrected the Cat Canyon field’s production capability to a peak in 1953. Millions of barrels of oil were recovered and even in 1983, production was still about 350 barrels a day.

One century after its discovery by Palmer Oil Company, the Cat Canyon oilfield had 243 active oil wells. In a state long known for its natural oil seeps, enhanced recovery technologies revived oil production in Santa Barbara County and California’s other heavy oil-producing regions.

To extract reserves previously considered unrecoverable, companies like HVI Cat Canyon (Greka Energy), ERG Resources, and others used tertiary thermal recovery techniques. Improved technologies have dramatically lessened dangers to the environment, but not eliminated them.

A 1927 Palmer Union Oil Company stock certificate purchased at a garage sale in 2008 sparked a legal battle with Coca-Cola.

In 2023, a U.S. District Court found HVI Cat Canyon Inc. (formerly Greka Oil & Gas Company) liable for oil spills and ordered the company to pay $40 million in civil penalties for the spills; $15 million for violations of federal regulations, and $2.5 million in cleanup costs.

The U. S. Energy Information Administration in 2013 ranked Cat Canyon as 17th on its list of the nation’s top 100 producing oilfields — with no company having partial ownership in Coca-Cola Company (see Not a Millionaire from Old Oil Stock).

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Palmer Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/palmer-oil-company. Last Updated: December 7, 2023. Original Published Date: December 7, 2023.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 19, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

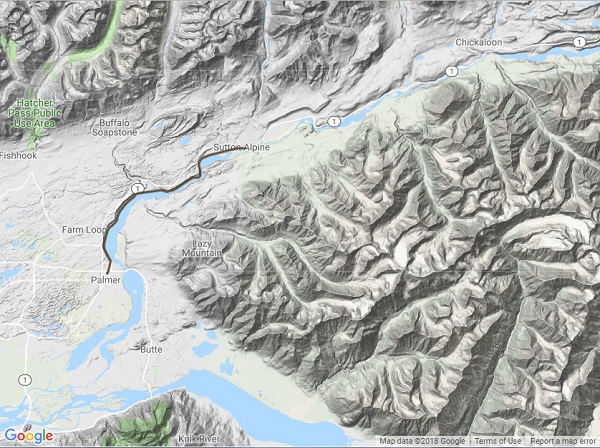

In the early 1950s, Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company marketed 300,000 shares of stock for $1 each.

Decades before Alaska became a state, many petroleum exploration companies drilled expensive dry holes in the remote U.S. territory. The Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company was among them.

Although drillers completed the first Alaska Territory commercial oil well in 1902, significant oilfield production did not arrive until 1957, two years before statehood.

Before switching to a rotary rig in 1954, the Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company drilled its Eureka No. 1 using this Walker-Neer Manufacturing Company cable-tool “spudder.” Photo courtesy the Anchorage Museum.

The July 1957 discovery well by Richfield Oil Corporation — later known as ARCO — successfully drilled near the Swanson River on the Kenai Peninsula. The first well, which produced 900 barrels of oil a day from 11,215 feet, revealed a giant oilfield.

Many Alaskans already had been wildcatting for black gold.

Among those searching for petroleum riches, Alaska Oil & Gas Development accepted the financial challenges of exploring unproven territory. William A. O’Neill and a former oilfield roughneck incorporated the company on October 31, 1952.

“Bill O’Neill, a local mining engineer and University of Alaska regent, and partner C.F. ‘Tiny’ Shield, a giant of a man, believed they could find oil in the Copper River Basin,” explained Jack Roderick in his 1997 book, Crude Dreams: A Personal History of Oil & Politics in Alaska.

“Before coming to Alaska in the early 1920s, Shield had been a cable-rig ‘tool pusher’ in Montana, Texas and California,” he added.

Within a year, Alaska Oil & Gas Development began drilling near “mud volcanoes” — sulfuric residues bubbling up from the valley floor — and near mud cliffs embedded with giant marine fossils, Roderick reported.

The Eureka No. 1 well with its Walker-Neer cable-tool rig at its remote site just off Glenn Highway about 125 miles northeast of Anchorage. Photo courtesy the Anchorage Museum.

Far from any oil or natural gas producing well in North America, the well site — known as a rank wildcat — was at Eureka Roadhouse, about 125 miles northeast of Anchorage, just 200 feet off the Glenn Highway (part of Alaska Route 1).

Risky Business

Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company offered 300,000 shares of stock at $1 per share, advertising in newspapers:

The money realized from the sale of this stock is being used to purchase equipment and finance operations for oil exploration in the Eureka-Nelchina location. The location of the first exploratory drill hole has been chosen by our consulting geologist after a geological survey of the area.

The Walker-Neer cable-tool rig reached about 2,500 feet deep before drilling was temporarily suspended at the site. A Texas geologist suggested converting to a rotary rig for greater depth. Photo courtesy the Anchorage Museum.

Drilling at the Eureka Roadhouse site began on September 20, 1953, using cable-tool technology — a Walker-Neer Manufacturing Company rig often called a spudder.

“By early 1954, the Eureka No. 1 well had been drilled down more than half a mile, but the antiquated equipment, making each day’s going tougher, eventually forced O’Neill and Shield to shut down the operation,” noted Roderick.

The limitations of outdated cable-tool technology — and the onset of Alaska’s winter — delayed but did not deter the men. “Shield traveled to Texas, and while looking up some tool pusher buddies, contacted Fort Worth independent James H. Snowden,” Roderick explained.

Snowden sent a geologist to Alaska to investigate the well. “He reported that by converting the cable-tool rug to a rotary, the Eureka well could be deepened to 5,500 feet,” Roderick reported.

By the summer of 1954, having switched the Walker-Neer spudder for a rotary rig, the Eureka No. 1 well reached about a mile in depth — but found no indications of oil.

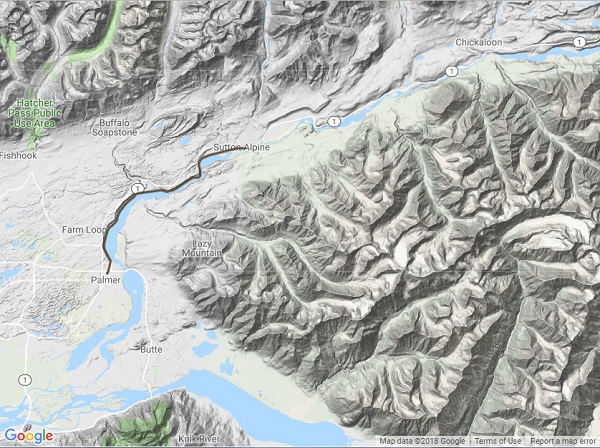

Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company spudded a well in the Matanuska Valley northeast of Anchorage in June 1953. Map courtesy USGS.

O’Neill and Shield tried again, drilling a second well near Houston, Alaska, on the Alaska Railroad line. It ended as a dry hole as well.

According to Roderick, Alaska Oil & Gas Development plugged and abandoned both wells by 1957. Another company also had tried to find oil in the Matanuska Valley, but failed before it could drill even one well (see Chickaloon Oil Company).

With its funds exhausted, the Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company failed to file a required report and was “involuntarily dissolved” by regulators.

In 1957, Richfield Oil Corporation made the first major discovery two years before Alaska statehood. The company struck the territory’s first commercial oil well at Swanson River on the Kenai Peninsula.

Discovery of the Prudhoe Bay field on Alaska’s North Slope in 1968 made the 49th state a world-class oil and natural gas producer. Prudhoe Bay, the largest oilfield in North America, in turn inspired the U.S. petroleum industry’s 1977 engineering marvel, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Crude Dreams: A Personal History of Oil & Politics in Alaska (1997); Kenai Peninsula Borough, Alaska (2012); From the Rio Grande to the Arctic: The Story of the Richfield Oil Corporation

(2012); From the Rio Grande to the Arctic: The Story of the Richfield Oil Corporation (1972). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1972). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “ Alaska Oil & Gas Development Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/alaska-oil-gas-development-company. Last Updated: November 22, 2023. Original Published Date: July 14, 2016.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 13, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

“You will feel pretty good some of these fine mornings when your shares jump to 5 or 10 for one.”

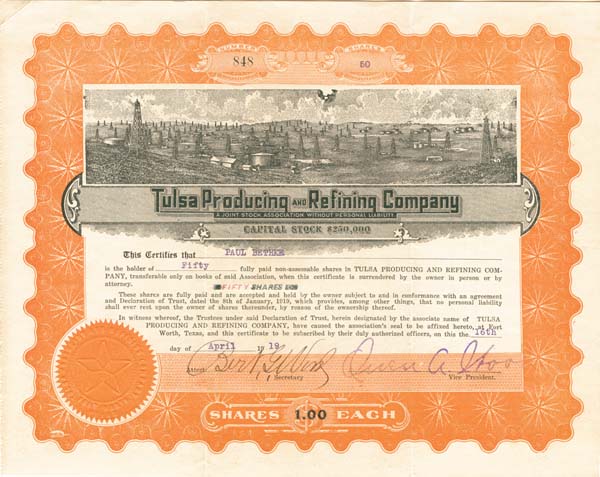

With oil booms in North Texas, especially along the Red River border with Oklahoma, Tulsa Producing and Refining Company incorporated to join the action in America’s growing Mid-Continent oil patch. In February 1919, the Texas El Paso Herald carried an advertisement for Tulsa Producing and Refining.

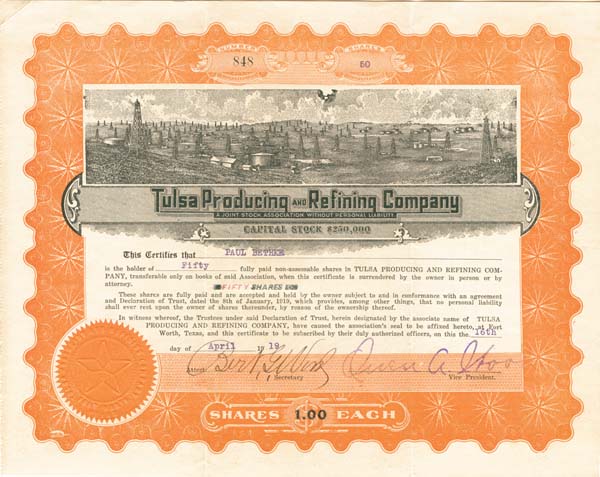

Stock certificate for the now defunct Tulsa Producing and Refining Company.

“A Strong, Solid Company With Two Wells Now Drilling” the advertisement proclaimed. It offered 250,000 shares of stock at $1 per share.

According to the company’s claims, the two wells were drilling in Comanche County, Texas, where Tulsa Producing and Refining reportedly held 1,000 acres under lease. Advertisements appeared in newspapers as far away as Pennsylvania, where America’s petroleum industry had begun in 1859 with the first U.S. oil well.

Frequent references were made to an oil boom in the remote region with 328,098 barrels of oil already produced. Even more enthusiastic advertisements about Texas discoveries followed in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times in May and June 1919.

“If either of these wells come in big, the shareholders of the Tulsa Producing & Refining Company will cash in strong – and do it quickly,” extolled perhaps one of the more conservative claims.

“You will feel pretty good some of these fine mornings when your shares jump to 5 or 10 for one,” added the company. “We believe this is going to happen – and happen soon, too.”

The predicted happiness apparently didn’t happen. All references to the company disappear thereafter.

Popular Certificate Vignette

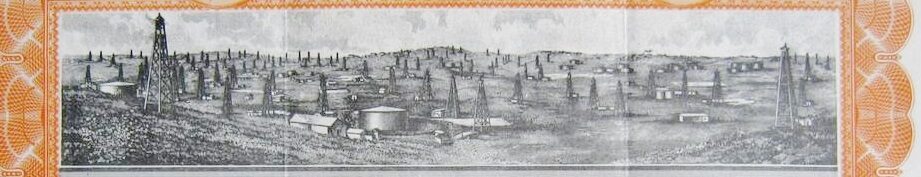

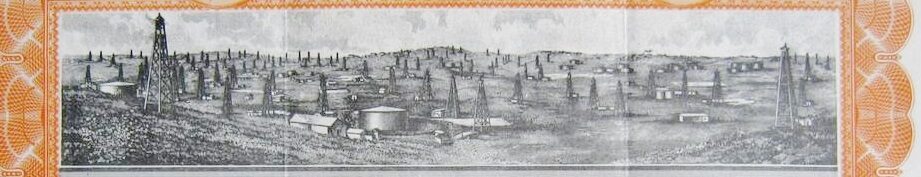

Seeking investors to chase “black gold” riches led to a surge in printing scenes of derricks on stock certificates.

Drilling booms often lead to many quickly formed (and quickly failed) exploration companies. As company executives rushed to print stock certificates, they often chose this same scene of derricks and oil tanks.

In the rush to promote their drilling plans, new companies had little time or money to find original art. One oilfield vignette from print shops proved particularly popular.

Among the most often used scenes was of a panorama of derricks found on certificates issued by the Double Standard Oil & Gas Company, the Evangeline Oil Company, the Buffalo-Texas Oil Company, and many other oil exploration ventures.

More articles about the attempts to join exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an the updated research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976 (1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin (2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Tulsa Oil and Refining Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/tulsa-producing-and-refining-company. Last Updated: November 14, 2023. Original Published Date: April 2, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 25, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

By the early 1900s, well-publicized “gushers” in California, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas had attracted many new and established oil exploration companies — and potential investors.

Despite national and sometimes international attention given to oilfield discoveries and the few companies that made “black gold” fortunes, hundreds of others went bankrupt trying. The Doughboy Oil Company’s investors did not find oil riches in Kansas. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Oct 24, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

New companies rush to drill at Spindletop Hill in early 1900s.

When a geyser of oil erupted in 1901 on Spindletop Hill, near Beaumont, Texas, it launched the greatest oil boom in America — far exceeding the nation’s first commercial oil well in 1859.

Many new and inexperienced oil ventures were formed almost overnight, including Buffalo Oil Company. The Spindletop field produced 43 million barrels of oil in its first four years, helping to launch the modern petroleum industry.

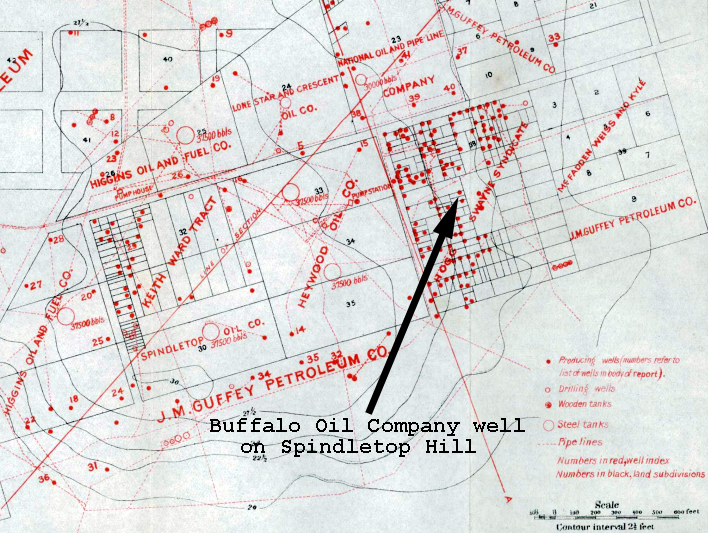

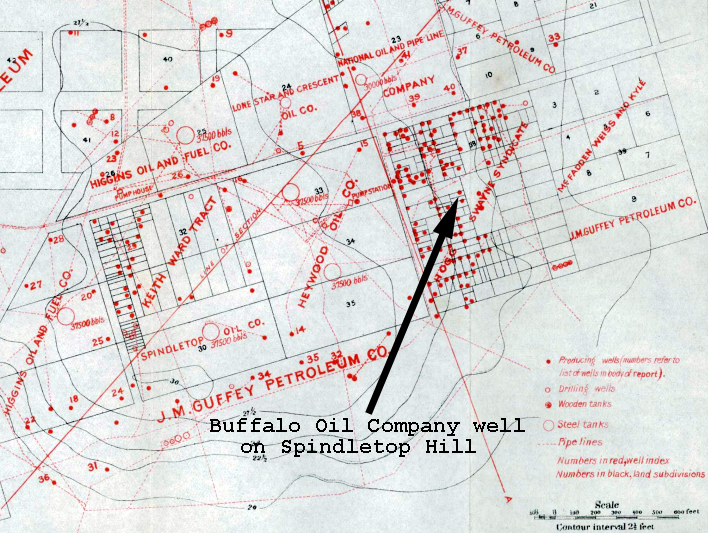

Among the 280 wells at Spindletop in 1902, Buffalo Oil completed a producing oil well at a depth of 960 feet on a lease of only 1/32 of an acre.

Buffalo Oil Company had quickly formed with $300,000 capitalization and stock listed with par value of 10 cents. Encouraged by the first well’s success, speculators invested in the company’s second. But by May 1902 the second Buffalo Oil well was “dry and abandoned” after reaching 1,400 feet deep.

As at least one expert noted at the time, the average life of flowing wells was short, “frequently but a few weeks and rarely more than a few months, with constantly diminishing output.”

Meanwhile, competing companies drove up the cost of drilling equipment and leases. Spindletop Hill was crowded with wooden derricks, oil storage tanks, and roughnecks.

Batson Oiflield

With signs of Spindletop production dropping, Buffalo Oil shifted operations to nearby Batson, where a 1903 well drilled by W.L. Douglas’ Paraffine Oil Company produced 600 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 790 feet. But the exploration company’s luck did not improve.

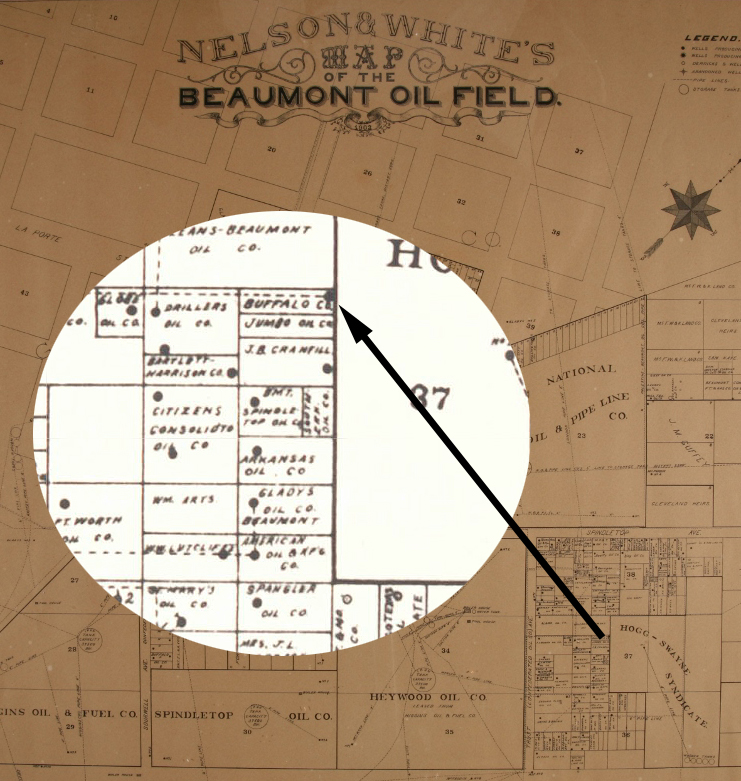

Map with detail showing Buffalo Oil Company lease among other drilling companies at Beaumont, Texas, home of a giant oilfield discovered in 1901.

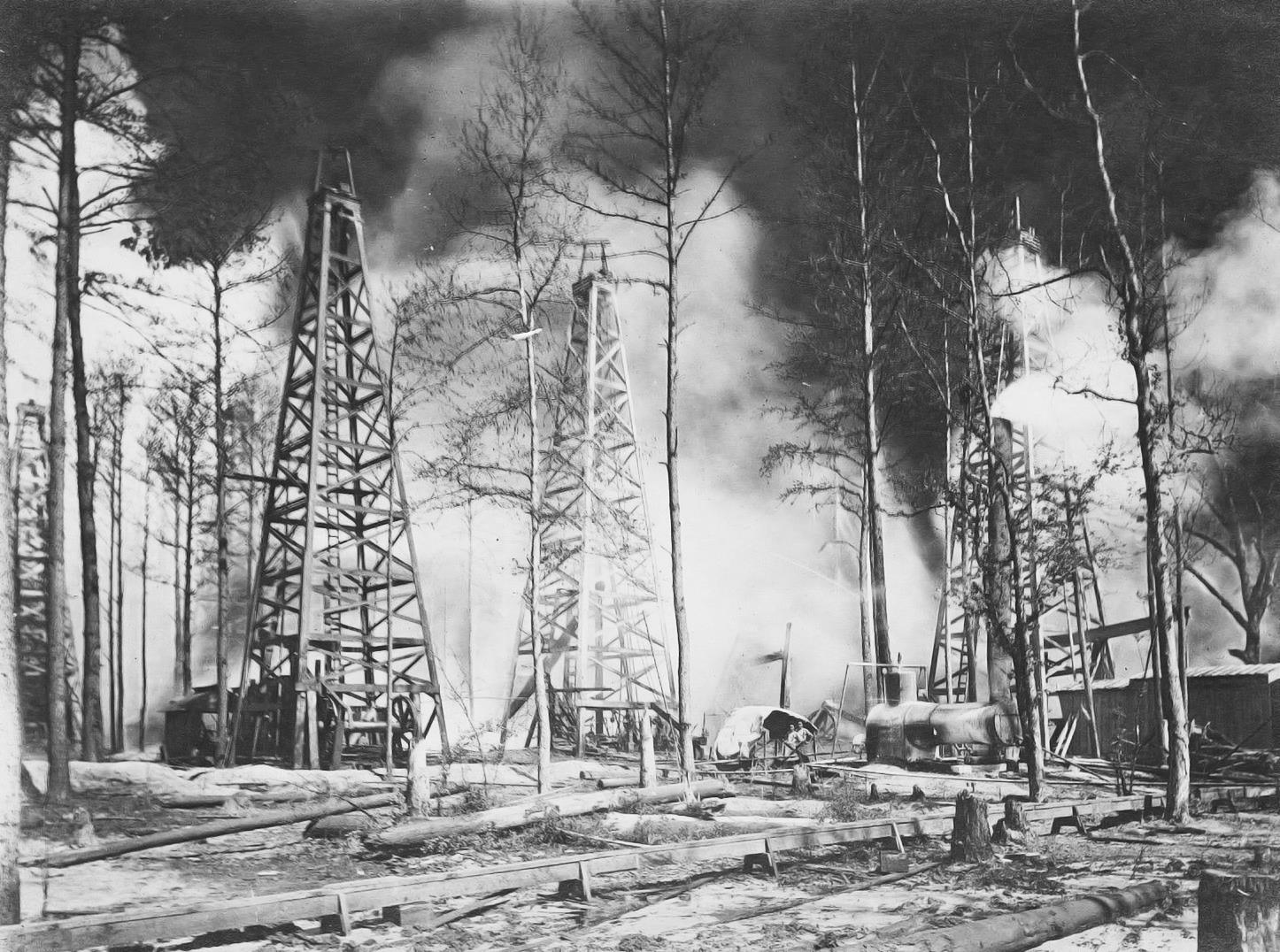

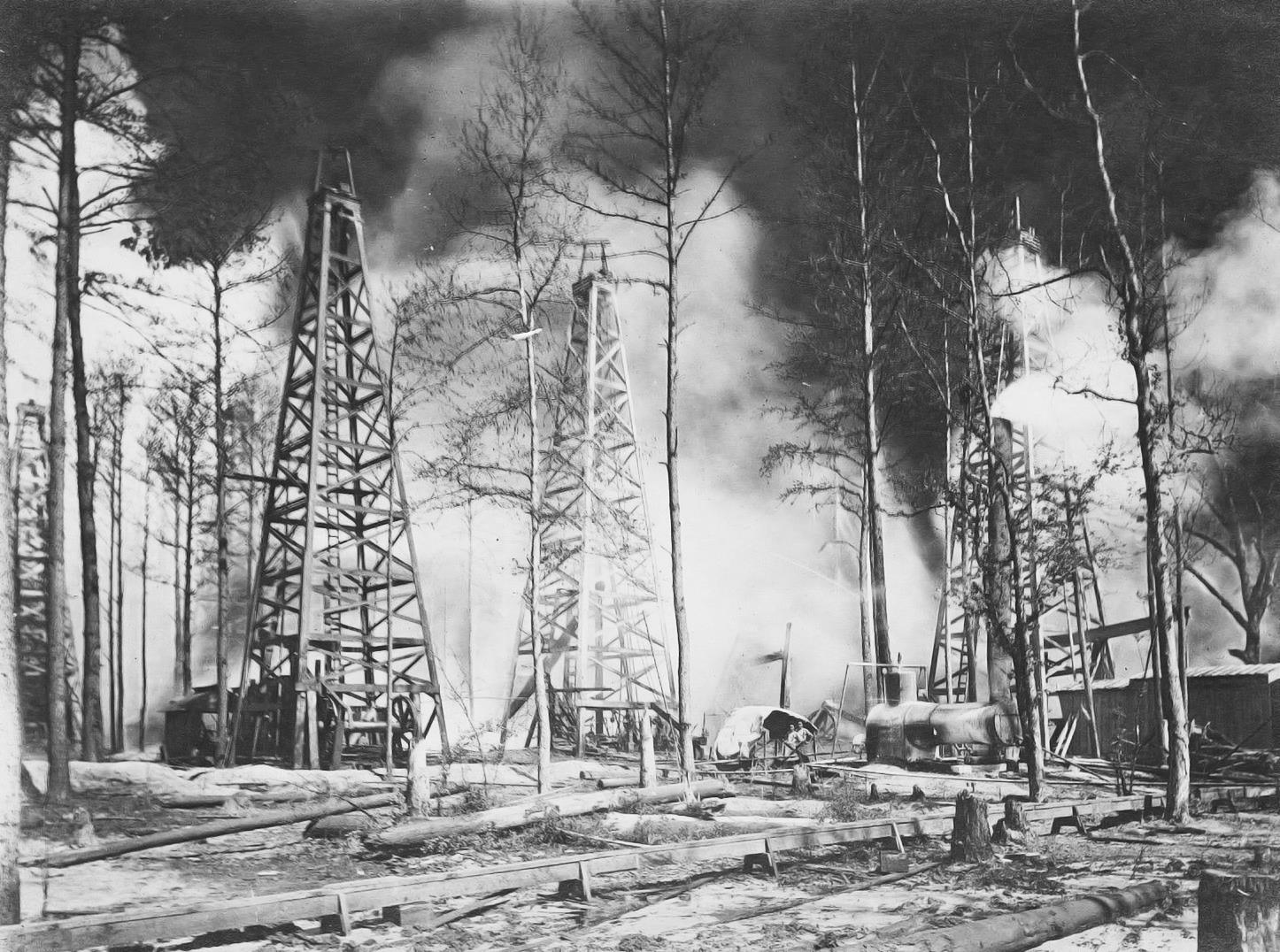

As the Batson field reached its peak monthly production of 2.6 million barrels of oil, a fire swept through the crowded oilfield.

“The fire burned furiously for several hours and though there were no fire appliances on the field, it is doubtless if equipment could have been used owing to the intense heat generated by the flames,” noted the Petroleum Review and Mining News.

Buffalo Oil Company’s well, derrick and equipment were completely destroyed.

Often caused by lightening strikes, oil tank fires were sometimes fought using cannons (learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires). After the Batson fire, the annual Buffalo Oil Company stockholder’s meeting took place in April 1904.

Fire engulfed the Batson oilfield in 1902, destroying the equipment and future of Buffalo Oil Company. Photo courtesy Traces of Texas.

“The company states that their recent investment at Batson so far has proved a serious loss to them, and the present outlook is very unfavorable,” reported the Petroleum Review and Mining News. But it got even worse.

Two weeks after the dire report to share owners, a second Batson fire destroyed another Buffalo Oil producing well and two 1,200-barrel storage tanks. Petroleum Review and Mining News concluded the fire “probably originated through an explosion in the pumping plant.”

The Batson oilfield would continue to produce for many years, but without Buffalo Oil Company. As late as 1993 the field yielded almost 200 barrels of oil a day, but Buffalo Oil was history without having paid a dividend.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Buffalo Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/buffalo-oil-company. Last Updated: October 31, 2023. Original Published Date: October 28, 2017.