by Bruce Wells | Mar 3, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Louisiana oil boom brings pipelines, refineries and competition.

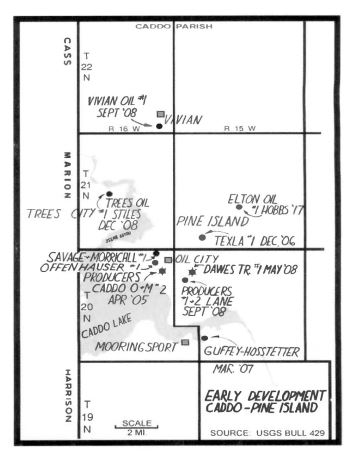

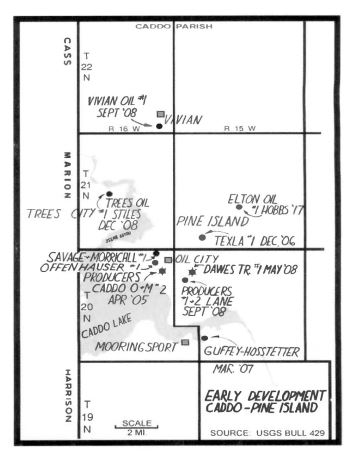

Claiborne Parish made headlines on January 12, 1919, when Consolidated Progressive Oil Company completed the discovery well for northern Louisiana’s prolific Homer oilfield. About 50 miles to the west, a 1905 oil discovery at Caddo-Pines near Shreveport had brought a rush of oil exploration to northern Louisiana.

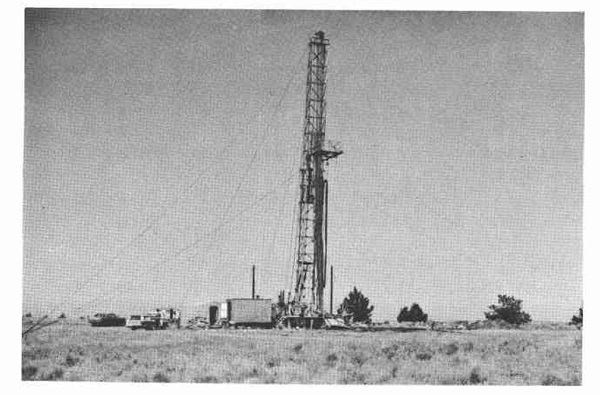

Caddo Lake drilling platforms – completed over water without a pier to shore – have been called America’s first true offshore oil wells. Exhibits at the state’s Oil City museum tell that story. Like Caddo-Pines, the Homer field was crowded with new companies within months after the discovery.

Petroleum production from the new field soon reached an aggregate of about 10,000 barrels of oil per day. Reporting from the Pennsylvania oil regions, Pittsburgh Press on September 21, 1919, proclaimed the “Homer Field is Sensation of Oil Industry.”

Detail from a panoramic “bird’s eye view” of the Homer oilfield circa 1920s. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Superior Oil Works

Paramount Petroleum Company began when the leadership of another company operating in the Homer oilfield decided to expand operations. Superior Oil Works officers, including President George A. Todd of Oklahoma City; Secretary and Purchasing Agent H.H. Todd of Vivian, Louisiana; and Treasurer D.C. Richardson of Shreveport organized the Paramount Petroleum Company.

Superior Oil Works had been formed to build and operate a refinery close to the Homer field. Capitalized at $300,000 with common stock issued, the company began construction in Superior, Louisiana, but its officers were by then contemplating the much-expanded venture — the formation of Paramount Petroleum to integrate exploration, production, transportation and refining under one organization.

Once established, the new company absorbed Superior Oil Works and looked for potential leases near the Consolidated Progressive Oil Company’s discovery well. As construction of the Superior refinery progressed, purchasing agent H.H. Todd advertised that Paramount Petroleum was “in the market for oil refinery equipment, boilers, stills, pumps, and plant machinery, etc.”

Paramount Petroleum made a deal with Consolidated Progressive Oil in May 1919, securing one-half interest in more than 11,000 acres of both proven and unexplored territory in Claiborne Parish. The acreage was already producing about 40,000 barrels of oil, ensuring the refinery would be supplied.

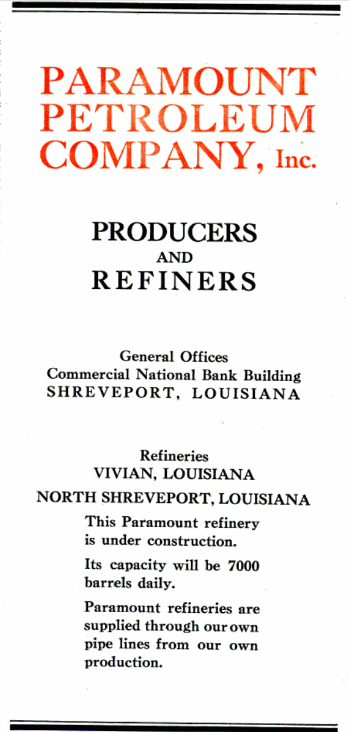

“A giant refining company has been organized recently in Shreveport to be known as the Paramount Petroleum Company,” noted the Oil Distribution News. The venture was capitalized at $10 million with half of its stock subscribed.

“Stock in this company has been consumed by the largest business and banking men of Shreveport,” added the Oil and Gas News. But the best news for investors was the headline: “Paramount Petroleum Gets 10,000 Barrel Well And Will Build Big Refinery.”

In March 1920, the Petroleum Age reported Paramount Petroleum “recently took over the under-construction Superior Oil Works refinery at Vivian [Superior], Louisiana, 23 miles north of Shreveport, to service Pine Island production.”

The publication added that another refinery was to be completed in north Shreveport in November 1920 “with a four-inch pipeline from the Homer field where Paramount Petroleum holds 4,700 acres.”

Paramount Petroleum Company’s newest refinery would be struggling by May 1921.

Within a month Paramount Petroleum was drilling in Claiborne Parish and shipping 400,600 barrels of oil a day. The company secured a $1 million mortgage from the Commercial National Bank of Shreveport and advertised, “Paramount refineries are supplied through our own pipelines from our own production.”

Paramount Petroleum in July 1920 completed the No. 5 Shaw well, which produced 500 barrels of oil a day from 2,090 feet deep in the Homer field. In August, the company’s No. 9 Shaw well become another 500-barrels-of-oil-a-day producer from a depth of 2,100 feet.

Anticipating more growth in oil production, Paramount Petroleum committed to an agreement for 300 tank cars from Standard Tank Car Company of St. Louis, Missouri.

“Not too bright”

“Paramount has just closed a deal for one half interest in 24 producing wells in the old Caddo field with 1,200 acres of proven territory on which many wells can yet be drilled,” reported the Petroleum Age in October 1920. “The production department of Paramount Petroleum is making splendid headway and with its large acreage, will no doubt greatly add to the earnings of the company.”

But the Petroleum Age reporter had got it wrong. By February 1921, Paramount Petroleum’s refinery at Superior was running at only about 50 percent capacity. Another trade publication reported the company’s prospects as “not too bright.”

Shipments from Paramount Petroleum’s Homer oilfield holdings dropped to just 168 barrels of oil a day. In May 1921 the struggling company leased its underused refinery and fleet of 390 tank cars to Lucky Six Oil Company for six months.

The Homer field attracted drillers from earlier discoveries at the nearby Caddo-Pines oilfields. Photo courtesy the Petroleum History Institute.

To the south, the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 oil gusher on January 10, 1921, had opened Arkansas’ El Dorado field and Lucky Six Oil Company had entered the scramble to exploit the new field’s huge production (578,000 barrels of oil in the month of May alone).

The oilfield discovery 15 miles north of the Louisiana border was the first Arkansas oil well. It attracted even more exploration and production companies to the region.

As competition intensified, Paramount Petroleum struggled to pay debts. It was unable to make a required $200,000 mortgage payment to Commercial National Bank of Shreveport in July 1921. The deal Paramount had struck with Consolidated Progressive Oil back in 1919 had become toxic.

The National Petroleum News reported on September 7, 1921, that Consolidated Progressive Oil was seeking a court-ordered receiver to take over Paramount Petroleum. The action was based on claims totaling $849,547 — and “averred acts jeopardizing the interests of creditors.” Among the allegations was “the effect that officials of the defendant concern have admitted in writing the company’s inability to meet present and maturing obligations.”

Paramount Petroleum’s epitaph was brief. “It is officially stated that this company is out of business,” reported Poor’s Cumulative Service in December 1921. “Its properties are to be sold by the sheriff December 24 and proceeds applied on the first Mortgage notes.”

The first Louisiana oil well had been drilled 17 years before the end of Paramount Petroleum. More stories about petroleum exploration and production companies trying to join drilling booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Louisiana’s Oil Heritage, Images of America (2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright AOGHS © 2025

Citation Information – Article Title: “Paramount Petroleum Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:httpshttps://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/paramount-petroleum-company. Last Updated: March 9, 2025. Original Published Date: August 15, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 17, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Oklahoma showman Maj. Gordon W. “Pawnee Bill” Lillie caught oil fever in 1918.

With America joining “the war to end all wars” in Europe and oil demand rising, a popular Oklahoma showman launched his own petroleum exploration and refining company.

Although not as well known as his friend Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody of Wyoming, Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie was “a showman, a teacher, and friend of the Indian,” according to his biographer.

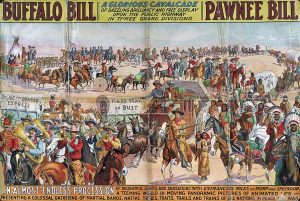

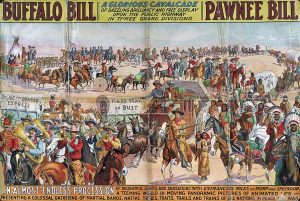

Pawnee Bill and Buffalo Bill combined their shows from 1908 to 1913 as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East.”

Maj. Lillie was admired for being a “colonizer in Oklahoma and builder of his state,” noted Stillwater journalist Glenn Shirley in his 1958 book Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie.

The two entertainers joined their shows in 1908 to form “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East,” promoted as “a glorious cavalcade of dazzling brilliancy,” noted Shirley, adding that the combined shows offered, “an almost endless procession of delightful sight and sensations.”

But times were changing as public taste turned to a new form of entertainment, motion picture shows. By 1913, the two showmen’s partnership was over and their western cavalcade foreclosed. Lillie turned to other ventures — real estate, banking, ranching, and like his former partner Cody, the petroleum industry.

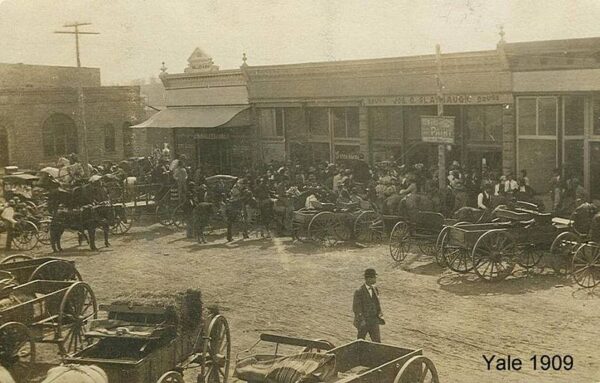

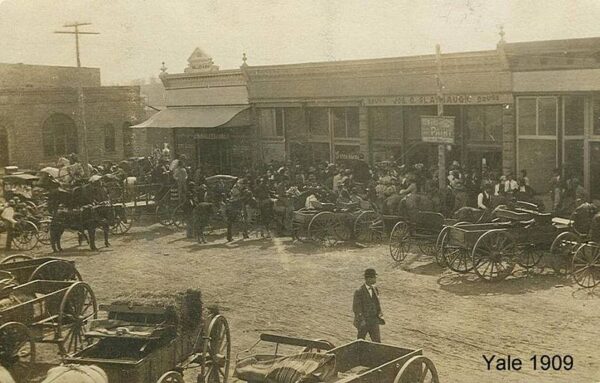

Oklahoma oilfield discoveries near Yale (population of only 685 in 1913) had created a drilling boom that made it home to 20 oil companies and 14 refineries. In 1916, Petrol Refining Company added a 1,000-barrel-a-day-capacity plant in Yale, about 25 miles south of Lillie’s ranch.

The trade magazine Petroleum Age, which had covered the 1917 “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery in Texas, reported that for Pawnee Bill, “the lure of the oil game was too strong to overcome.”

Obsolete financial stock certificates with interesting histories like Pawnee Bill Oil Company are valued by collectors.

The Oklahoma showman founded the Pawnee Bill Oil Company on February 25, 1918, and bought Petrol Refining’s new “skimming” refinery in March.

An early type of refining, skimming (or topping) removed light oils, gasoline and kerosene and left a residual oil that could also be sold as a basic fuel. To meet the growing demand for kerosene lamp fuel, early refineries built west of the Mississippi River often used the inefficient but simple process.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie (1860-1942).

Lillie’s company became known as Pawnee Bill Oil & Refining and contracted with the Twin State Oil Company for oil from nearby leases in Payne County.

Under headlines like “Pawnee Bill In Oil” and “Hero of Frontier Days Tries the Biggest Game in All the World,” the Petroleum Age proclaimed:

“Pawnee Bill, sole survivor of that heroic band of men who spread the romance of the frontier days over the world…who used to scout on the ragged edge of semi-savage civilization, is doing his bit to supply Uncle Sam and his allies with the stuff that enables armies to save civilization.”

Post WWI Bust

By July 30, 1919, Pawnee Bill Oil (and Refining) Company had leased 25 railroad tank cars, each with a capacity of about 8,300 gallons. But the end of “the war to end all wars” drastically reduced demand for oil and refined petroleum products. Just two years later, Oklahoma refineries were operating at about 50 percent capacity, with 39 plants shut down.

Although Lillie’s refinery was among those closed, he did not give up. In February 1921, he incorporated the Buffalo Refining Company and took over the Yale refinery’s operations. He was president and treasurer of the new company. But by June 1922, the Yale refinery was making daily runs of 700 barrels of oil, about half its skimming capacity.

The Pawnee Bill Oil Company held its annual stockholders meetings in Yale, Oklahoma, an oil boom town about 20 miles from Pawnee Bill’s ranch.

“At the annual stockholders’ meeting held at the offices of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company in Yale, Oklahoma, in April, it was voted to declare an eight percent dividend,” reported the Wichita Daily Eagle. “The officers and directors have been highly complimented for their judicious and able handling, of the affairs of the company through the strenuous times the oil industry has passed through since the Armistice was signed.”

The Kansas newspaper added that although many Independent refineries had been sold at receivers’ sale, “the financial condition of the Pawnee Bill company is in fine shape,”

Buffalo Bill’s Shoshone Oil

What happened next has been hard to determine since financial records of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company are rare. A 1918 stock certificate signed by Lillie, valued by collectors one hundred years later, could be found selling online for about $2,500.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie’s friend and partner Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody also caught oil fever, forming several Wyoming oil exploration ventures, including the Shoshone Oil Company.

In 1920, yet another legend of the Old West — lawman and gambler Wyatt Earp — began his a search for oil riches on a piece of California scrubland. One century later, his Kern County lease still paid royalties; learn more in Wyatt Earp’s California Oil Wells.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie (1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Pawnee Bill Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pawnee-bill-oil-company. Last Updated: February 19, 2025. Original Published Date: February 24, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 4, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

A 1954 well drilled by the Ohio Oil Company reached more than four miles deep.

Founded in 1887 by Henry M. Ernst, the Ohio Oil Company got its exploration and production start in northwestern Ohio, at the time a leading oil-producing region. Two years later, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust purchased the growing company — known as “The Ohio” — and in 1905 moved headquarters from Lima to Findlay.

Soon establishing itself as a major pipeline company, by 1908 the Ohio controlled half of the oil production in three states. The company resumed independent operation in 1911 following the dissolution of the Standard Oil monopoly. The new Ohio Oil’s exploration operations expanded into Wyoming and further westward.

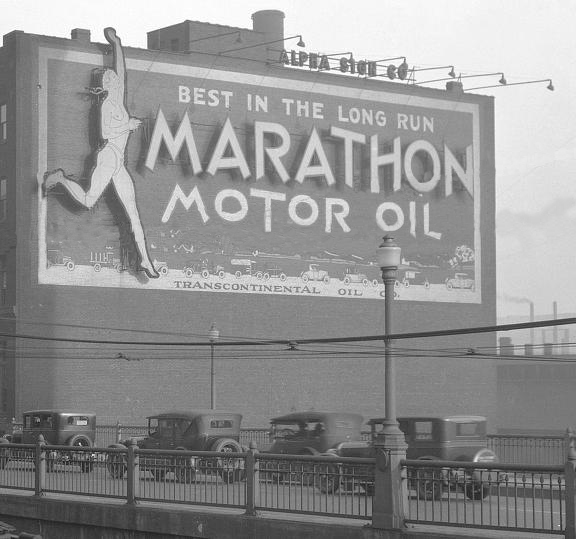

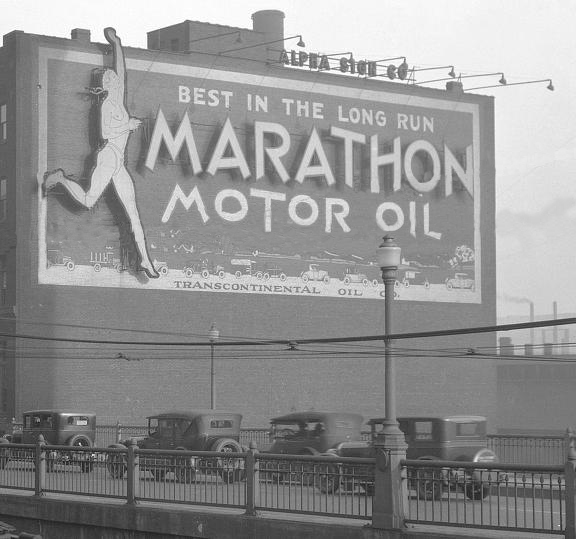

The Ohio Oil Company in 1930 purchased Transcontinental Oil, a refiner that had marketed gasoline under the trademark “Marathon” since 1920. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

By 1915, the company’s infrastructure had added 1,800 miles of pipeline as well as gathering and storage facilities from its newly acquired Illinois Pipe Line Company. The Ohio then purchased the Lincoln Oil Refining Company to better integrate and develop more crude oil outlets.

“Ohio Oil saw the increasing need for marketing their own products with the ever-increasing supply of automobiles appearing on the primitive roads,” explained Gary Drye in a 2006 forum at Oldgas.com.

The company ventured into marketing in June 1924 by purchasing Lincoln Oil Refining Company of Robinson, Illinois. With an assured supply of petroleum, the Ohio Oil’s “Linco” brand quickly expanded.

The Ohio Oil Company marketed its oil products as “Linco” after purchasing the Lincoln Oil Refinery in 1920. Undated photo of a station in Fremont, Ohio.

Meanwhile, a subsidiary in 1926 co-discovered the giant Yates oilfield in the Permian Basin of New Mexico and West Texas. “With huge successes in oil exploration and production ventures, Ohio Oil realized they needed even more retail outlets for their products,” Drye reported. By 1930, the company distributed Linco products throughout Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Kentucky.

Marathon of Ohio Oil

In 1930 Ohio Oil purchased Transcontinental Oil, a refiner that had marketed gasoline under the trademark “Marathon” across the Midwest and South since 1920. Acquiring the Marathon product name included the Pheidippides Greek runner trademark and the “Best in the long run” slogan.

Adopted in 2011, the third logo for corporate branding in Marathon Oil’s 124-year history.

According to Drye, Transcontinental “can best be remembered for a significant ‘first’ when in 1929 they opened several Marathon stations in Dallas, Texas in conjunction with Southland Ice Company’s ‘Tote’m’ stores (later 7-Eleven) creating the first gasoline/convenience store tie-in.”

The Marathon brand proved so popular that by World War II the name had replaced Linco at stations in the original five-state territory. After the war, Ohio Oil continued to purchase other companies and expand throughout the 1950s.

Ohio Oil’s California Record

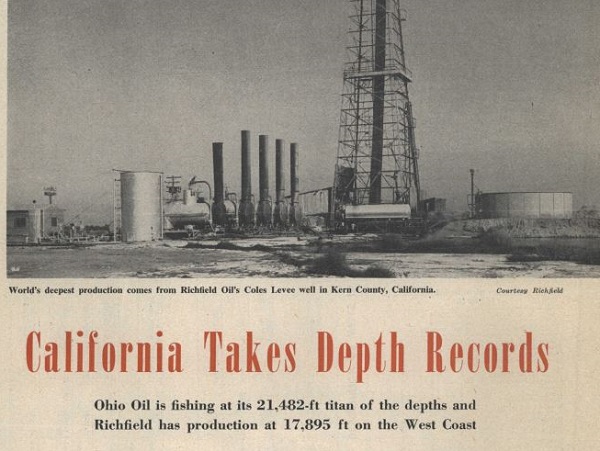

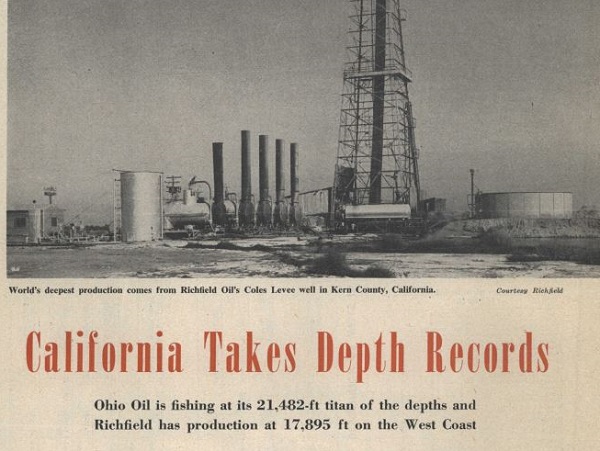

As deep drilling technologies continued to advance in the 1950s, a record depth of 21,482 feet was reached by the Ohio Oil Company in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

Petroleum Engineer magazine in 1954 noted the well set a record despite being “halted by a fishing job.”

The deep oil well drilling attempt about 17 miles southwest of Bakersfield in prolific Kern County, experienced many challenges. A final problem led to it being plugged with cement on December 31, 1954. At more than four miles deep, down-hole drilling technology of the time was not up to the task when the drill bit became stuck.

The challenge of retrieving obstructions from deep in a well’s borehole – “fishing” – has challenged the petroleum industry since the first tool stuck at 134 feet and ruined a well spudded just four days after the famous 1859 discovery by Edwin Drake in Pennsylvania (see The First Dry Hole).

In a 1954 article about deep drilling technology, The Petroleum Engineer noted the Kern County well of Ohio Oil — which would become Marathon Oil — set a record despite being “halted by a fishing job.” The well was a financial loss.

A 1953 Kern County well drilled by Richfield Oil Corporation produced oil from a depth of 17,895 feet, according to the magazine. At the time, the average U.S. cost for the nearly 100 wells drilled below 15,000 feet was about $550,000 per well. Learn more California petroleum exploration history by visiting the West Kern Oil Museum.

More than 630 exploratory wells with a total footage of almost three million feet were drilled in California during 1954, according to the American Association of Petroleum Geologists — the AAPG, established in 1917.

In 1962, celebrating its 75th anniversary, The Ohio changed its name to Marathon Oil Company and launched its new “M” in a hexagon shield logo design. Other milestones include:

1981 – U.S. Steel (USX) purchased the company.

1985 – Yates field produced its billionth barrel of oil.

1990 – Marathon opened headquarters in Houston.

2005 – Marathon became 100 percent owner of Marathon Ashland Petroleum LLC, which later became Marathon Petroleum Corp.

2011 – Completed a $3.5 billion investment in the Eagle Ford Shale play in Texas.

On June 30, 2011, Marathon Oil became an independent upstream company and unveiled an “energy wave” logo as it prepared to separate from Marathon Petroleum, based in Findlay. Read a more detailed history in Ohio Oil Company and visit the Hancock Historical Museum in Findlay.

On May 29, 2024, Marathon Oil announced it was being acquired by ConocoPhillips in an all-stock transaction valued at $22.5 billion.

______________________________

Recommended Reading: Portrait in Oil: How Ohio Oil Company Grew to Become Marathon (1962). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1962). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

______________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Marathon of Ohio Oil.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/marathon-ohio-oil. Last Updated: February 3, 2025. Original Published Date: December 28, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 22, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Rise and fall of a California oil exploration company.

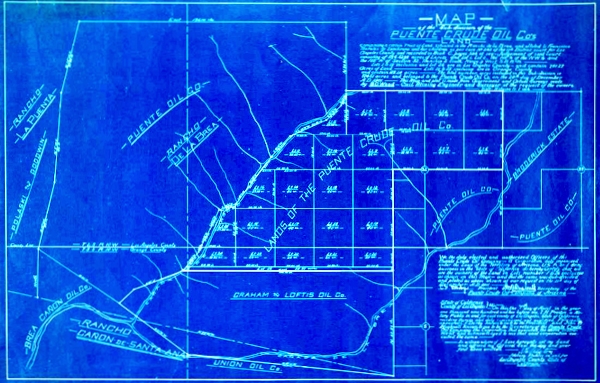

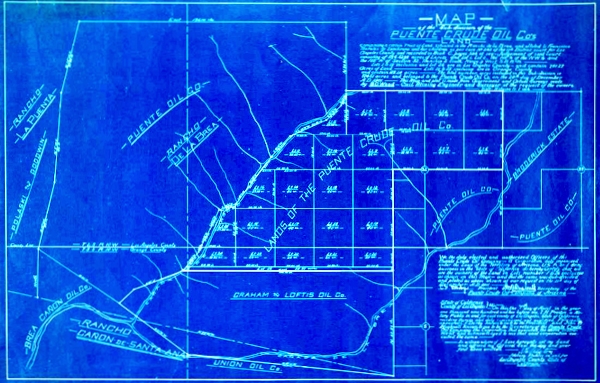

A new “black gold” rush in California took off in 1886 after William Rowland and partner William Lacy completed several producing oil wells at Rancho La Puente. Their company, Rowland & Lacy (later called the Puente Crude Oil Company), helped reveal the Puente oilfield.

The exploration venture — and a more successful one with a similar name, the Puente Oil Company — were among those seeking oil in southern California at the turn of the century. By 1912, many inexperienced companies had drilled more than 100 wells in the Fullerton area southeast of the Los Angeles field. Two expensive “dry holes” were completed by the Puente Crude Oil Company.

Puente Crude Oil Company was one of many small early 20th-century ventures hoping to find oil in southern California’s prolific oilfields at Brea Canyon and Fullerton.

Initially capitalized with $500,000, Puente Crude Oil offered stock to the public at 10 cents a share in 1900, but its two unsuccessful wells in the Puente field’s eastern extension brought the company to a quick financial crisis.

One well was lost to a “crooked hole” and the other found only traces of oil and natural gas as enthusiastic advertisements continued to solicit investment. Some ads referred to the widely known Sunset oilfield, discovered in 1892 in Kern County to the north.

By May 1901 company stock was offered at two cents per share to relieve indebtedness and enable further drilling on the company’s 870 acres in Rodeo Canyon. One year later, San Bernardino newspapers reported the company in trouble.

“This history of misadventure has not been pleasing to the stockholders of the Puente Crude Oil Company,” noted one article. “An auditing committee was appointed for the purpose of examining the books and accounts of the company,” it added.

Further reports in 1902 noted the company had issued no statements, “financial or otherwise,” for a year. Puente Crude Oil Company is absent from records thereafter.

South of Los Angeles, in Orange County, the Brea Museum and Heritage Center tells the story of the Olinda Oil Well No. 1 well of 1898 – one of many important California petroleum discoveries. Visit the Olinda Oil Museum and Trail at 4025 Santa Fe Road in Brea.

Much of Puente Oil’s former oil-producing land would later be managed by the Puente Hills Landfill Native Habitat Preservation Authority. In 2022, the Port of Los Angeles handled more than 220 million metric tons — 20 percent of all incoming cargo for the United States.

The stories of exploration and production (E&P) companies joining U.S. petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Los Angeles, California, Images of America (2001). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2001). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Puente Crude Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/puente-crude-oil-company. Last Updated: January 30, 2025. Original Published Date: July 2, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 14, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Wildly optimistic promotions during WWI and some drilling, but no gushers.

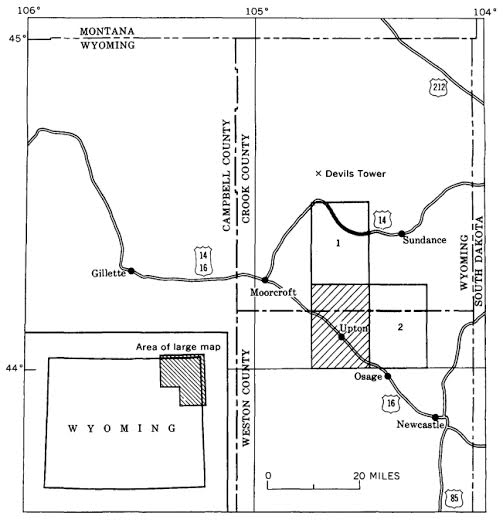

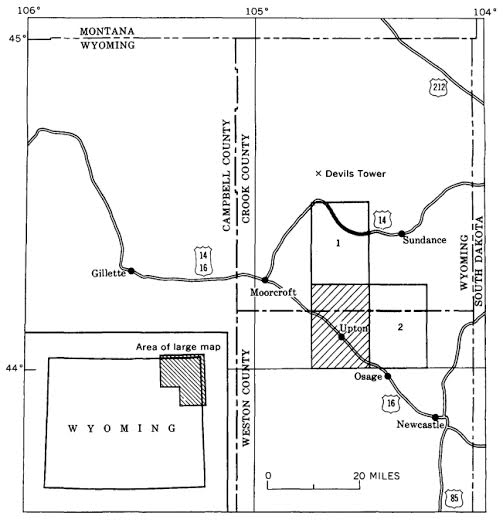

“Oil Excitement at Rocky Ford Field Near Sundance,” proclaimed a front page of the Moorcroft (Wyoming) Democrat on September 14, 1917, describing a “big drill” of the Wyoming-Dakota Company.

“Rocky Ford, the seat of the oil activities in Crook county is about the busiest place around,” the newspaper continued. “Cars come and go, people congregate and the steady churning of the two big rigs continues perpetually.”

Not finished with its excited reporting, the Moorcroft Democrat noted: “Excitement has reached the zenith of tension, and with each gush of the precious fluid, oil stock climbs another notch. The big drill of the Wyoming-Dakota Co. has been pulled from their deep hole until spring. The drill reached 600 feet and was in oil.”

The Rapid City, South Dakota, oil exploration company — reported to have one producing well and three more drilling — was capitalized $500,000 with a nominal par value of 25 cents per share. All the leases were in Crook County and included 3,200 acres in Lime Butte field; 10,000 acres in Rocky Ford field; and 4,000 acres in Poison Creek field.

Since Wyoming would not pass its first “Blue Sky” to prevent fraudulent promotions until 1919, Wyoming-Dakota Oil’s newspaper ads often rivaled patent medicine exaggerations. For example, one ad noted “geologists claim this showing indicates alone 500,000 barrels to the acre.”

Since Wyoming would not pass its first “Blue Sky” to prevent fraudulent promotions until 1919, Wyoming-Dakota Oil’s newspaper ads often rivaled patent medicine exaggerations. For example, one ad noted “geologists claim this showing indicates alone 500,000 barrels to the acre.”

Wyoming-Dakota Oil further enticed investors with, “Your Chance Has Come if you want to make money in Oil.” In Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the Sells Investment Company offered Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company stock reportedly after “a careful selection of conservative issues from among the thousand prospects, offering same to you before higher prices prevail or its present substantial position has been discounted by professional traders. A good clean cut speculation of this character may mean a fortune. Watch this company for sensational developments.”

The United States had entered World War I in April 1917; by November newspapers reported Francis Peabody, chairman of the Coal Committee of the Council of National Defense, was telling the U.S. Senate Public Lands Committee that the country was not producing enough oil to win the war.

“He said if nothing were done to develop new wells the reserve supply would he exhausted in twelve months and production would be 50,000,000 barrels less than requirements,” one newspaper noted. Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company executives took advantage of the opportunity.

“The (war) situation outlined leads us to suggest that you investigate Wyoming-Dakota Oil. ‘We are doing our bit’ by drilling night and day. Ours is an investment worth while. The allotment of Treasury stock at 25 cents is almost sold out and the Directors will advance the price of stock to 50 cents a share (100 per cent on your present investment) on December 15th, 1917.”

The Wyoming-Dakota Oil promotion continued: “By that time our newspaper announcement in the Eastern cities, pointing out the enormous acreage, present production and negotiations for additional valuable holdings will be made known to millions of seasoned investors in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston and Pittsburgh. We feel confident this will result in a demand for this stock that will send the present market price skyward. We trust you will see the wisdom of prompt action before all available stock at 25 cents per share has been purchased by other investors.”

In early 1918, Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company had drilled wells in the Upton-Thornton oilfield and was “holding out high hope of bringing in a gusher in few days.” In July, the Laramie Daily Boomerang reported the company had “two rigs going steadily in Crook County’s Rocky Ford field” — but no oil gushers

Growing investor pessimism was reflected in Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company’s stock prices, which fell in over-the-counter markets from 75 cents bid in June 1919 to 50 cents bid at the end of September. By March 1920, brokers offered 5,000 shares or any part thereof at 5 cents a share.

A final blow to the company was reported in the Laramie Republican of July 25, 1921: “Wyoming-Dakota…has completed pulling the casing from the well which it has been drilling north of town, after having struck a formation said to be granite, at a depth of 715 feet,”

The Laramie newspaper remained optimistic. “While this has a tendency to retard the activities of other interests, it is by no means stopping them entirely and it is to be hoped that another well will be started this summer.”

That did not happen. Reports on Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company disappeared for the next 24 years, until a court summons was published in the January 25, 1945, Sundance (Wyoming) Times. The summons said Wyoming-Dakota Oil — address or place of residence to plaintiff unknown — was being sued in the Sixth District Court of Wyoming.

The world war-inspired oil exploration company has since faded into history, and its stock certificates are valued only by scripophily collectors. For the true story behind a Texas oilfield that played a vital role in the “War to End All Wars,” see Roaring Ranger wins WWI.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Wyoming-Dakota Company” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/wyoming-dakota-oil-company. Last Updated: March 31, 2025. Original Published Date: January 14, 2016.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 2, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Three petroleum exploration companies risked everything on one well in their gamble to to find an Oregon oilfield.

The lure of petroleum wealth invited speculators practically since the first U.S. oil well of 1859 in Pennsylvania. Exploratory wells especially have remained a high-risk investment since almost nine out of ten of these “wildcat” wells fail to produce commercial amounts of oil.

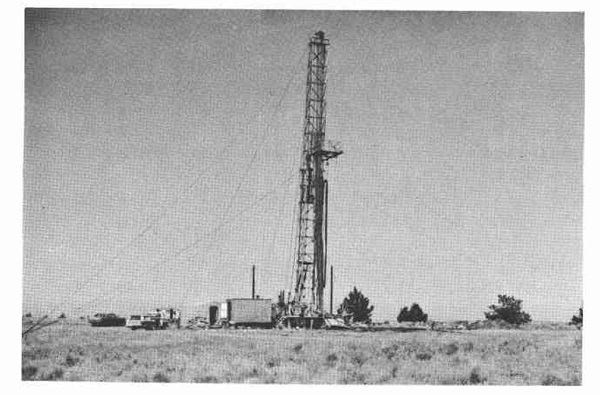

The Morrow No. 1 well, an ill-fated wildcat well first drilled in 1952 in Jefferson County, Oregon. Photo courtesy Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, “The Ore Bin,” Vol. 32, No.1, January 1970.

With under-capitalized operations turning to public sales of stock to raise money, many small ventures have been forced to bet everything on drilling a first successful well to have a chance at a second. Drilling a producing well can bring some wealth, but a “dry hole” brings bankruptcy.

And so it was in the 1950s on a remote hillside in Jefferson County, Oregon, where three companies searched for riches from the same well.

Northwestern Oils Inc.

The first of these three Oregon wildcatters, Northwestern Oils, incorporated in 1951 with $1 million capitalization in order to “carry on business of mining and drilling for oil.”

With offices in Reno, Nevada, in early 1952 Northwestern Oils began drilling a test well about eight miles southeast of Madras, Oregon. Using a cable-tool drilling rig (see Making Hole – Drilling Technology), drillers reached a depth of 3,300 feet on the Baycreek anticline before work was suspended because of “lost circulation troubles.”

Circulation troubles continued with the Morrow No. 1 well – also known as the Morrow Ranch well – in Jefferson County (Section 18, Township 12 South, range 15 East). By March 1956, with no money and no additional drilling possible, Northwestern Oils’ assets were “seized for non-payment of delinquent internal revenue taxes due from the corporation” and auctioned off at the Jefferson County courthouse.

Central Oils Inc.

Central Oils (Seattle) also was formed in 1956. With plans to join the other rare Oregon wildcatters, the company registered with the Security and Exchange Commission on July 30, 1958. It sought to sell one million shares of stock to the public at 10 cents a share. Proceeds would finance leasing and drilling, just like Northwestern Oils.

Central Oils received a permit to deepen Northwestern Oils’ old Morrow Ranch well in 1966 and planned to continue drilling with a cable-tool rig. Nothing happened.

“Commencement of this venture has been delayed until the spring of 1967,” one newspaper reported. But Central Oils had run afoul of the SEC. Oregon regulators recorded the well abandoned as of September 12, 1967, and Central Oils “out of business; no assets.”

Robert F. Harrison

In May 1968, Robert F. Harrison and his associates took over the same well — this time with plans to deepen it to more than 5,000 feet. But two years later the drilling effort was still stuck at a depth of 3,300 feet. Desperate, Harrison tried to clear the borehole by applying technologies for Fishing in Petroleum Wells.

On February 2, 1971, an intra-office report noted that R.F. Harrison “will abandon as soon as weather permits,” never having exceeded the original Northwestern Oils total depth of 3,300 feet. It would be a dry hole.

Harrison finally plugged and abandoned the Morrow No. 1 well as of October 12, 1971. Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries has identified the stubborn nonproducer as well number 36-031-00003. There has never been a successful oil well drilled in Oregon.

America’s first dry hole was drilled in 1859 by John Grandin of Pennsylvania – near and just a few days after the first commercial discovery. In 2014, U.S. oil wells produced more than 8.7 million barrels of oil every day, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil on the Brain: Petroleum’s Long, Strange Trip to Your Tank (2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration

(2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration (1979).

(1979).

Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oregon Wildcatters.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/oregon-wildcatters. Last Updated: February 26, 2025. Original Published Date: January 29, 2016.

(2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.