by Bruce Wells | Sep 1, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

September 1, 1862 – Union taxes Manufactured Gas –

A new federal tax of up to 15 cents per thousand cubic feet was placed on manufactured gas to help fund the Civil War. Often processed from coal and stored in large gasometers, “town gas” had become popular for street and residential lighting. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle accused the local gas company of passing on the new tax, which “shifts from its shoulders its share of the burdens the war imposes and places it directly on their customers.” (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Aug 26, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Gov. James “Big Jim” Hogg stipulated in his will that mineral rights should not be sold.

In 1917, the Tyndall-Wyoming Oil Company’s No. 1 Hogg well discovered oil south of Houston and ended a streak of dry holes dating back to 1901, when former Texas Governor James S. Hogg first thought oil might be there and leased the land.

The Lone Star State’s 20th governor, “Big Jim” Hogg, died in 1906 without witnessing the Texas drilling boom he helped launch. But his unwavering belief in finding oil in the Gulf Coast’s geologic salt domes would benefit the Texas petroleum industry.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jan 10, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

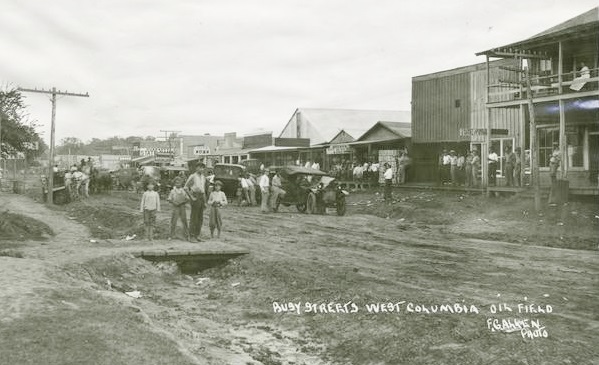

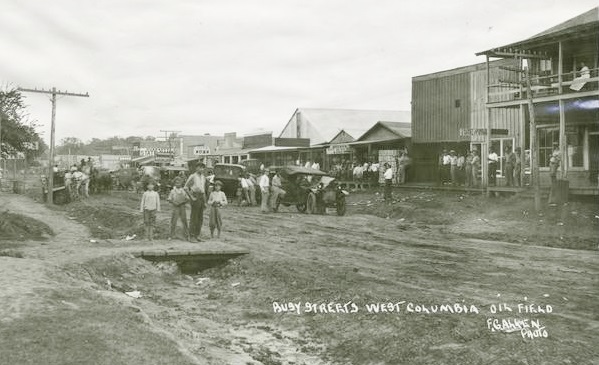

Lucky Jim Oil Company was created in March 1919 to pursue opportunities in the newly discovered West Columbia oilfield in Brazoria County, Texas (visit the Columbia Historical Museum in West Columbia to learn more about the first capital of the Republic of Texas).

The Brazoria County oilfield, 50 miles southwest of Houston, “was the youngest of the first rank salt dome oilfields of the Texas-Louisiana coastal region, and at present is the most productive of these fields,” reported the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) in 1921.

Wind knocked down the first derrick of a Lucky Jim Oil Company well drilled in 1919. The well reached 3,340 feet before the company gave up – and reorganized as the Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company.

Like many competing exploration companies formed during Texas drilling booms, Lucky Jim Oil Company did not survive its first dry hole. A Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company fared no better.

West Columbia field

Wildcatters had become interested in the West Columbia after oil discoveries on a lease owned by a former Texas governor. Gov. J.S. “Big Jim” Hogg first thought oil might be there and leased the land in 1901 (learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells).

When the Hogg No. 2 well was completed at 600 barrels of oil a day in January 1918, speculators rushed to lease nearby acreage. The 20-square-mile oilfield yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918.

The Hogg discovery wells led to a local boom that attracted inexperienced, even fraudulent, drilling companies that would not long survive. They planned to drill near property with proven oil production.

Advertisements appeared in Texas newspapers that included $10 per share stock promotions enticing investment in the West Columbia oilfield — with a promise to pay out 75 percent of any net earnings to shareholders. The ads assured investors of early dividends and admonished, “Buy Today, Tomorrow May Be Too Late.”

The Texas Company (later Texaco) was among companies that found success in the 20-square-mile oilfield in Brazoria County. The field yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918 alone.

Hedging against a dry hole and gambling on higher oil prices, Lucky Jim Oil declared in 1919, “We have immense holdings that we should be able to sell out on the present rise of prices in West Columbia, and pay our stockholders three or four for one on their investment without drilling a well.”

With funding from stock sales, the company was able to begin drilling its first well, the Brown No. 1, proclaiming it to be “within 1,800-feet of the Texas Company’s 20,000 barrel gusher.”

Drilling progressed for a few months until the derrick reportedly collapsed in high winds during a September storm. After rebuilding the wooden structure and resuming drilling, the well reached 3,340 feet. It was an expensive dry hole.

Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company

Within a month of the failed exploratory well, a reorganized Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company made its first appearance and tried again to secure funding to launch drilling operations in the crowded West Columbia oilfield.

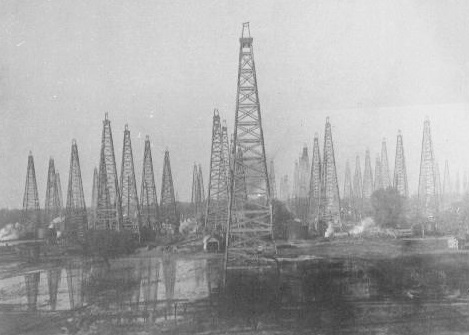

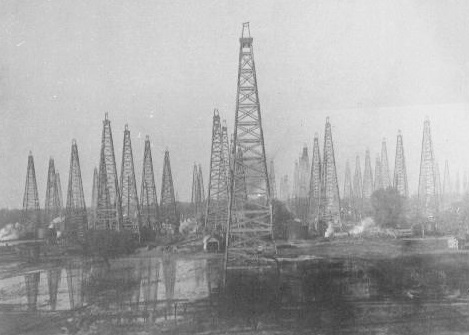

A drilling boom resulted in the West Columbia oilfield reaching its annual peak production of 12.5 million barrels of oil a few years after its discovery.

The new company did not succeed in raising enough capital and soon disappeared, along with many other such “poor boy” operations in South Texas at the time. Only larger companies could absorb costs of a dry hole and continue drilling.

The Texas Company (later Texaco) – after drilling several dry holes in the West Columbia field – in July 1920 brought in the Abrams No. 1 well, which produced 26,500 barrels a day for six weeks (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

By 1921, the West Columbia field reached its peak annual production of 12.5 million barrels of oil — but by then the Lucky Jim Oil Company and Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company were both history.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lucky Jim Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/lucky-jim-oil-company. Last Updated: September 4, 2021. Original Published Date: September 8, 2015.

.