by Bruce Wells | Jan 28, 2026 | Petroleum Products

G.M. scientists discover the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead gasoline.

General Motors scientists in 1921 discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead as an additive to gasoline. By 1923, many American motorists would be driving into service stations and saying, “Fill ‘er up with Ethyl.”

Early internal combustion engines frequently suffered from “knocking,” the out-of-sequence detonation of the gasoline-air mixture in a cylinder. The constant shock added to exhaust valve wear and frequently damaged engines.

Automobiles powered with gasoline had been the least popular models at the November 1900 first U.S. auto show in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

General Motors chemists Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles F. Kettering tested many gasoline additives, including arsenic.

On December 9, 1921, after five years of lab work to find an additive to eliminate pre-ignition “knock” problems of gasoline, General Motors researchers Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles Kettering discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead.

Early experiments at GM examined the properties of knock suppressors such as bromine, iodine, and tin — comparing these to new additives such as arsenic, sulfur, silicon, and lead.

The world’s first anti-knock gasoline containing a tetra-ethyl lead compound went on sale at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio. A bolt-on “Ethylizer” can be seen running vertically alongside the visible reservoir. Photo courtesy Kettering/GMI Alumni Foundation.

When the two chemists synthesized tetraethyl lead and tried it in their one-cylinder laboratory engine, the knocking abruptly disappeared. Fuel economy also improved. Ethyl vastly improved gasoline performance.

“Ethylizers” debut in Dayton

Although being diluted to a ratio of one part per thousand, the lead additive yielded gasoline without the loud, power-robbing knock. With other automotive scientists watching, the first car tank filled with leaded gas took place on February 2, 1923, at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio.

In the beginning, GM provided Refiners Oil Company and other service stations special equipment, simple bolt-on adapters called “Ethylizers” to meter the proper proportion of the new additive.

“By the middle of this summer you will be able to purchase at approximately 30,000 filling stations in various parts of the country a fluid that will double the efficiency of your automobile, eliminate the troublesome motor knock, and give you 100 percent greater mileage,” Popular Science Monthly reported in 1924.

By the late 1970s, public health concerns resulted in the phase-out of tetraethyl lead in gasoline, except for aviation fuel.

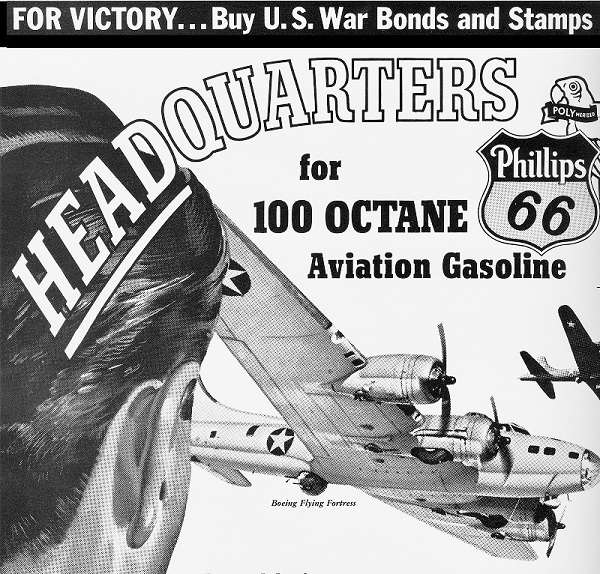

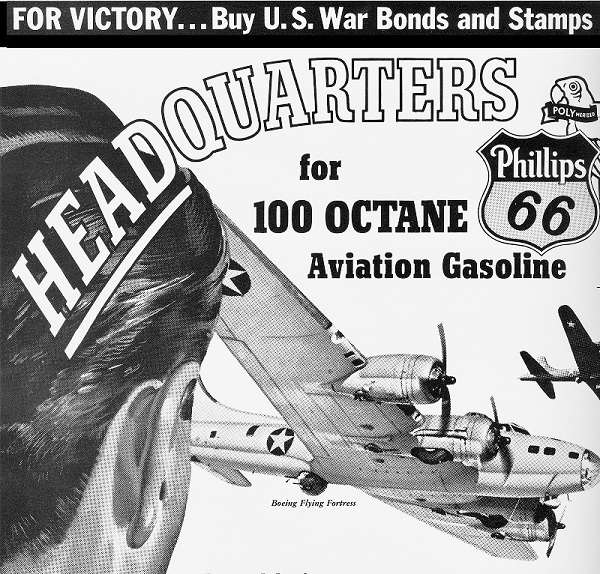

Anti-knock gasoline containing a tetraethyl lead compound also proved vital for aviation engines during World War II, even as danger from the lead content increasingly became apparent.

Powering Victory in World War II

Aviation fuel technology was still in its infancy in the 1930s. The properties of tetraethyl lead proved vital to the Allies during World War II. Advances in aviation fuel increased power and efficiency, resulting in the production of 100-octane aviation gasoline shortly before the war.

Phillips Petroleum — later ConocoPhillips — was involved early in aviation fuel research and had already provided high-gravity gasoline for some of the first mail-carrying airplanes after World War I.

Phillips Petroleum produced tetraethyl leaded aviation fuels from high-quality oil found in Osage County, Oklahoma, oilfields.

Phillips Petroleum produced aviation fuels before it produced automotive fuels. The company’s gasoline came from the high-quality oil produced from Oklahoma’s Seminole oilfields and the 1917 Osage County oil boom.

Although the additive’s danger to public health was underestimated for decades, tetraethyl lead has remained an ingredient of 100-octane “avgas” for piston-engine aircraft.

Tetraethyl Lead’s Deadly Side

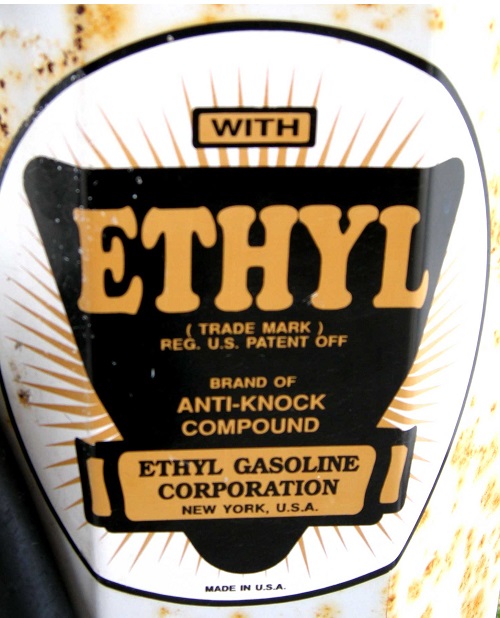

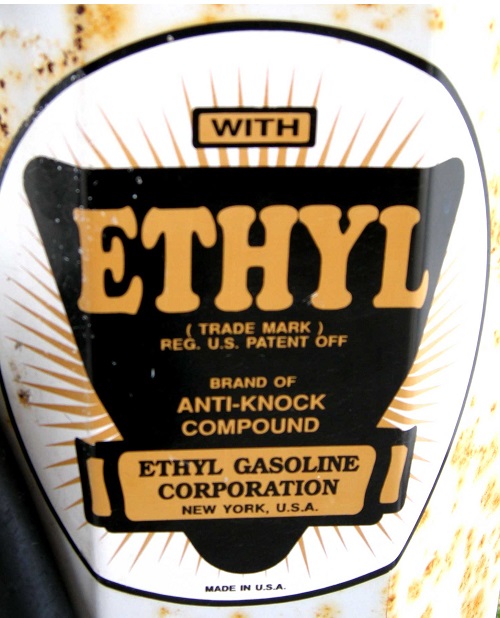

Leaded gasoline was extremely dangerous from the beginning, according to Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer. “GM and Standard Oil had formed a joint company to manufacture leaded gasoline, the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation,” she noted in a January 2013 article. Research focused solely on improving the formula, not on the danger of the lead additive.

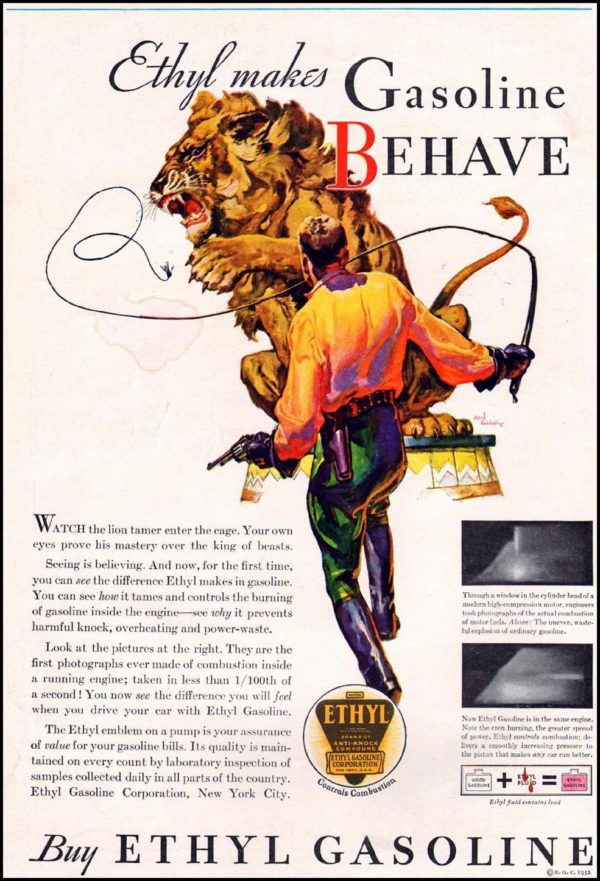

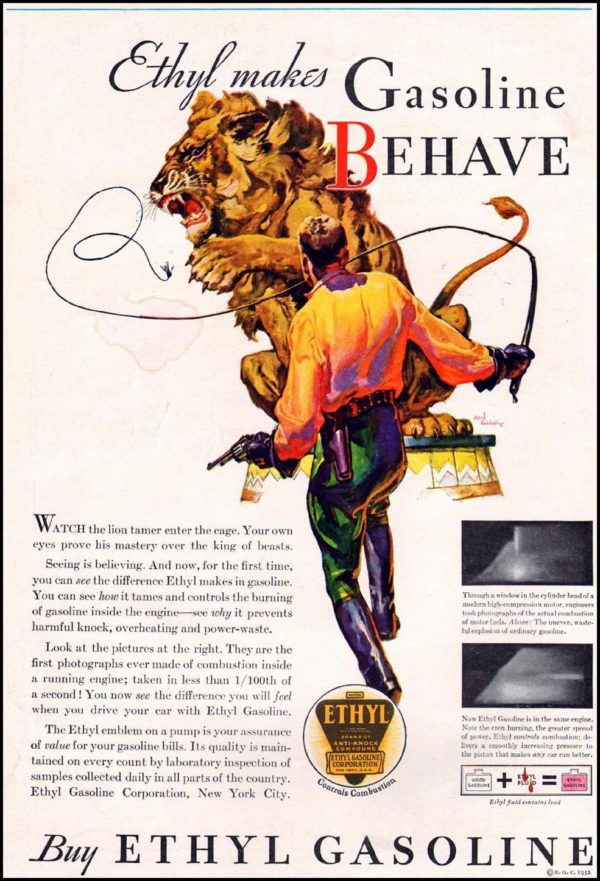

A 1932 magazine advertisement promoted the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation fuel additive as a way to improve high-compression engine performance.

“The companies disliked and frankly avoided the lead issue,” Blum wrote in “Looney Gas and Lead Poisoning: A Short, Sad History” at Wire.com. “They’d deliberately left the word out of their new company name to avoid its negative image.”

In 1924, dozens were sickened, and five employees of the Standard Oil Refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, died after they handled the new gasoline additive.

By May 1925, the U.S. Surgeon General called a national tetraethyl lead conference, Blum reported. An investigative task force was formed. Researchers concluded there was ”no reason to prohibit the sale of leaded gasoline” as long as workers were well protected during the manufacturing process.

So great was the additive’s potential to improve engine performance, the author notes, by 1926 the federal government approved continued production and sale of leaded gasoline. “It was some fifty years later — in 1986 — that the United States formally banned lead as a gasoline additive,” Blum added.

By the early 1950s, American geochemist Clair Patterson discovered the toxicity of tetraethyl lead; phaseout of its use in gasoline began in 1976 and was completed by 1986. In 1996, EPA Administrator Carol Browner declared, “The elimination of lead from gasoline is one of the great environmental achievements of all time.”

Learn more about high-octane aviation fuel in Flight of the Woolaroc.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps (2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website, expand historical research, and extend public outreach. For annual sponsorship information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All right reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ethyl Anti-Knock Gas.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/tetraethyl-lead-gasoline. Last Updated: December 4, 2025. Original Published Date: December 7, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 4, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

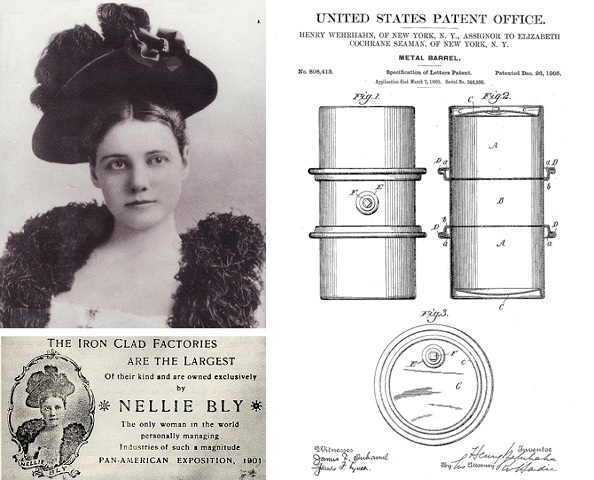

Densmore brothers advanced oil industry infrastructure — and helped create “QWERTY” typewriter keyboard.

As Northwestern Pennsylvania oil production skyrocketed following the Civil War, railroad oil tank cars fabricated by two brothers improved shipment volumes from oilfields to kerosene refineries. The tank car designed by James and Amos Densmore would not last, but more success followed when Amos invented a new keyboard arrangement for typewriters.

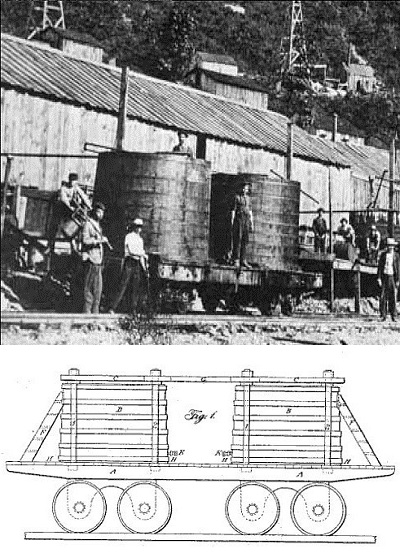

Flatbed railroad cars with two wooden oil tank cars became the latest advancement in oilfield infrastructure after the Densmore brothers patented their design on April 10, 1866.

The inventors from Meadville, Pennsylvania, had developed an “Improved Car for Transporting Petroleum” one year earlier in America’s booming oil regions. The first U.S. oil well had been drilled just seven years earlier along Oil Creek in Titusville.

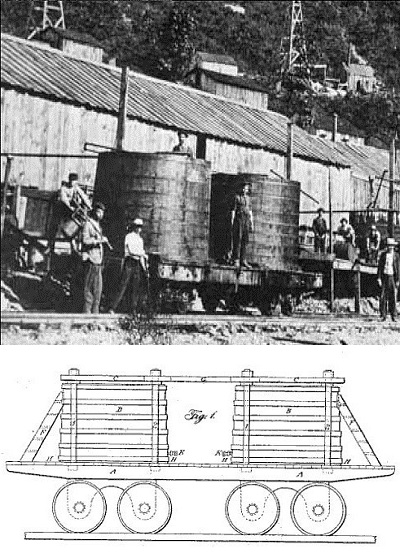

The first practical petroleum railway tank car was invented in 1865 by James and Amos Densmore at the Miller Farm along Oil Creek, Titusville, Pennsylvania. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

Using an Atlantic & Great Western Railroad flatcar, the brothers secured two tanks to ship oil in bulk. The patent (no. 53,794) described and illustrated the railroad car’s design.

The nature of our invention consists in combining two large, light tanks of iron or wood or other material with the platform of a common railway flat freight-car, making them practically part of the car, so as they carry the desired substance in bulk instead of in barrels, casks, or other vessels or packages, as is now universally done on railway cars.

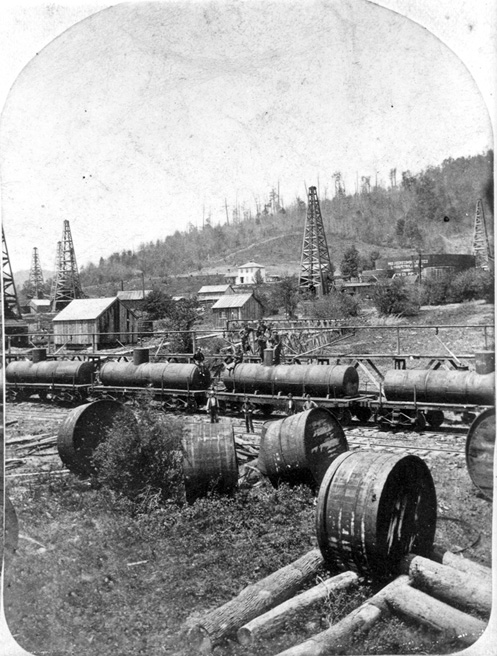

Development of railroad tank cars came when traditional designs, including the flatcar, hopper, and boxcar, proved inadequate for large amounts of oil — often shipped in 42-gallon barrels.

New designs were born out of necessity, as the fledgling oil industry demanded a better car for the movement of its product, according to American-Rails.com.

“Before the car was developed, railroads used a combination of boxcars, flatcars, and gondolas to haul everything from lumber and coal to crude oil, molasses, and water (by use of barrels),” noted Adam Burns in 2022. “One of the most prolific car types you will find moving within a freight train today is the tank car.”

Prone to leaks and top heavy, Densmore tank cars provided a vital service, if only for a few years before single, horizontal tanks replaced them.

According to transportation historian John White Jr., the Densmore brothers’ oil tank design essentially consisted of a flat car with wooden vats attached. “The Central Pacific is known to have used such specialized cars to transport water, he noted in his 1995 book, The American Railroad Freight Car.

“However, prior to the discovery of oil by Colonel Edward (sic) Drake near Titusville, Pennsylvania, on August 27, 1859, the tank car was virtually non-existent,” added White, a former curator of Transportation at the Smithsonian Institution.

Dual Tank Design

The brothers further described the use of special bolts at the top and bottom of their tanks to act as braces and “to prevent any shock or jar to the tank from the swaying of the car while in motion.”

A Pennsylvania Historical Commission marker on U.S. 8 south of Titusville commemorates the Densmore brothers’ significant contribution to petroleum transportation technology. Dedicated in 2004, the marker notes:

The first functional railway oil tank car was invented and constructed in 1865 by James and Amos Densmore at nearby Miller Farm along Oil Creek. It consisted of two wooden tanks placed on a flat railway car; each tank held 40-45 barrels of oil. A successful test shipment was sent in September 1865 to New York City. By 1866, hundreds of tank cars were in use. The Densmore Tank Car revolutionized the bulk transportation of crude oil to market.

The benefit of such railroad cars to the early petroleum industry’s infrastructure was immense, especially as more Americans eagerly sought oil-refined kerosene for lamps.

Despite design limitations that would prove difficult to overcome, independent producers took advantage of the opportunity to transport large amounts of petroleum. Other transportation methods required teamsters hauling barrels to barges on Oil Creek and the Allegheny River to get to kerosene refineries in Pittsburgh.

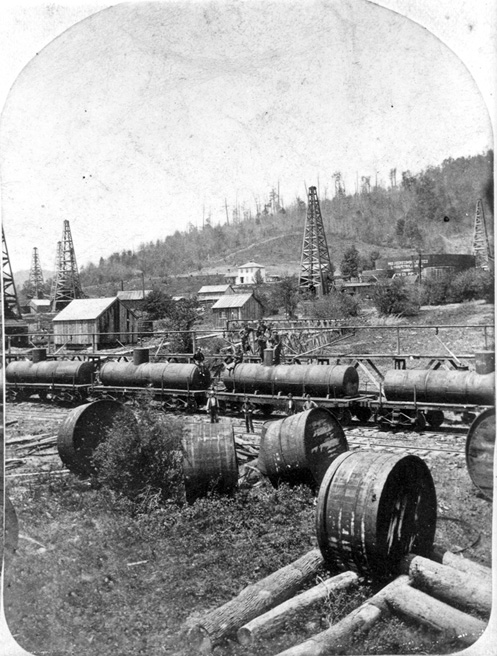

Riveted cylindrical iron tank cars replaced the Densmore brothers’ dual wooden tanks — seen here discarded. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

As larger refineries were constructed, it was found that it cost $170 less to ship 80 barrels of oil from Titusville to New York in a tank car instead of individual barrels. But the Densmore cars had flaws, notes the Pennsylvania Historical Commission.

They were unstable, top heavy, prone to leaks, and limited in capacity by the eight-foot width of the flatcar. Within a year, oil haulers shifted from the Densmore vertical vats to larger, horizontal riveted iron cylindrical tanks, which also demonstrated greater structural integrity during derailments or collisions.

The same basic cylindrical design for transporting petroleum can be seen as modern railroads load products from corn syrup to chemicals — all in a versatile tank car that got its start in the Pennsylvania oil industry.

The largest tank car ever placed into regular service was Union Tank Car Company’s UTLX 83699, rated at 50,000 gallons in 1963 and used for more than 20 years. A 1965 experimental car built by General American Transportation, the 60,000-gallon “Whale Belly,” GATX 96500, is now on display at the National Museum of Transportation in Saint Louis.

1863 Tank Car Patents

Although not manufactured, other inventors came up with new ways for transporting oil from booming oilfields. John Scott of Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, on January 20, 1863, patented (No. 37,461) a rectangular design for his “car for carrying petroleum, etc.”

John Clark of Canandaigua, New York, on November 3, 1863, was awarded a patent (No. 40,458) for another “improvement in cars for carrying petroleum.” His design put a long and flat sheet-metal tank under an ordinary freight car.

Finally, a “Petroleum Car” design with a cylindrical shape similar to modern railroad tank cars was patented (No. 38,765) on June 2, 1863, by Samuel J. Seely of Bookland, New York. The Seely patent might be the first design for a petroleum car shaped like those in use today.

Oil Tanks to Typewriters

Although the Densmore brothers left the oil region by 1867 — their inventiveness was far from over. In 1875, Amos Densmore assisted Christopher Sholes in rearranging the “type writing machine” keyboard so that commonly used letters no longer collided and got stuck. The “QWERTY” arrangement vastly improved Shole’s original 1868 invention.

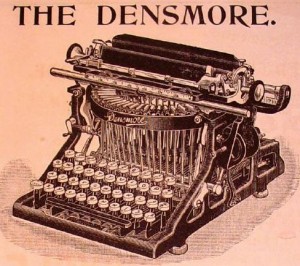

Amos Densmore helped invent one of the first practical typewriters.

Following his brother’s work with Sholes, inventor of the first practical typewriter, James Densmore’s oilfield financial success helped the brothers establish the Densmore Typewriter Company, which produced its first model in 1891. Few historians have made the oil patch to typewriter keyboard connection — including Densmore biographers.

The Pennsylvania Historical Commission reported that biographies of the Densmore brothers — and their personal papers at the Milwaukee Public Museum — all refer to their innovative typewriters, “but make no mention of their pioneering accomplishment in railroad tank car design.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Early Days of Oil: A Pictorial History of the Beginnings of the Industry in Pennsylvania (2000); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2000); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Densmore Oil Tank Cars.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/densmore-oil-tank-car. Last Updated: July 14, 2025. Original Published Date: April 7, 2013.

(2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.