by Bruce Wells | Nov 13, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

“You will feel pretty good some of these fine mornings when your shares jump to 5 or 10 for one.”

With oil booms in North Texas, especially along the Red River border with Oklahoma, Tulsa Producing and Refining Company incorporated to join the action in America’s growing Mid-Continent oil patch. In February 1919, the Texas El Paso Herald carried an advertisement for Tulsa Producing and Refining.

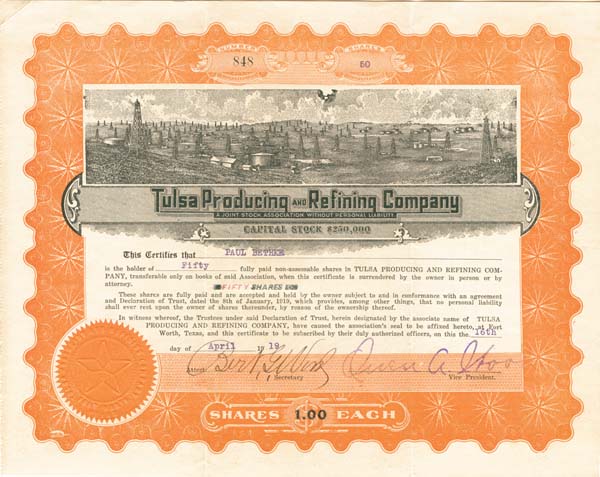

Stock certificate for the now defunct Tulsa Producing and Refining Company.

“A Strong, Solid Company With Two Wells Now Drilling” the advertisement proclaimed. It offered 250,000 shares of stock at $1 per share.

According to the company’s claims, the two wells were drilling in Comanche County, Texas, where Tulsa Producing and Refining reportedly held 1,000 acres under lease. Advertisements appeared in newspapers as far away as Pennsylvania, where America’s petroleum industry had begun in 1859 with the first U.S. oil well.

Frequent references were made to an oil boom in the remote region with 328,098 barrels of oil already produced. Even more enthusiastic advertisements about Texas discoveries followed in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times in May and June 1919.

“If either of these wells come in big, the shareholders of the Tulsa Producing & Refining Company will cash in strong – and do it quickly,” extolled perhaps one of the more conservative claims.

“You will feel pretty good some of these fine mornings when your shares jump to 5 or 10 for one,” added the company. “We believe this is going to happen – and happen soon, too.”

The predicted happiness apparently didn’t happen. All references to the company disappear thereafter.

Popular Certificate Vignette

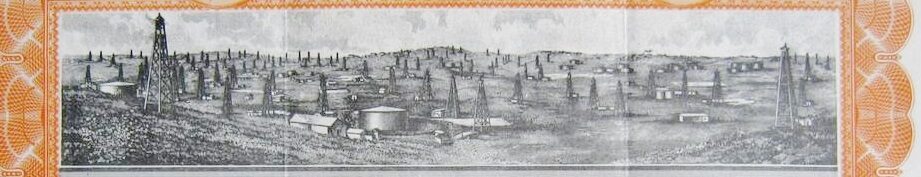

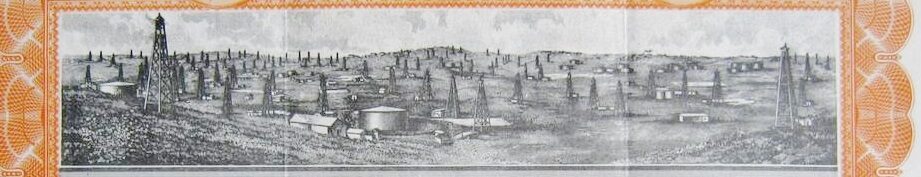

Seeking investors to chase “black gold” riches led to a surge in printing scenes of derricks on stock certificates.

Drilling booms often lead to many quickly formed (and quickly failed) exploration companies. As company executives rushed to print stock certificates, they often chose this same scene of derricks and oil tanks.

In the rush to promote their drilling plans, new companies had little time or money to find original art. One oilfield vignette from print shops proved particularly popular.

Among the most often used scenes was of a panorama of derricks found on certificates issued by the Double Standard Oil & Gas Company, the Evangeline Oil Company, the Buffalo-Texas Oil Company, and many other oil exploration ventures.

More articles about the attempts to join exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an the updated research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The fire in the rock: A history of the oil and gas industry in Kansas, 1855-1976 (1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin (2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Tulsa Oil and Refining Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/tulsa-producing-and-refining-company. Last Updated: November 14, 2023. Original Published Date: April 2, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 24, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

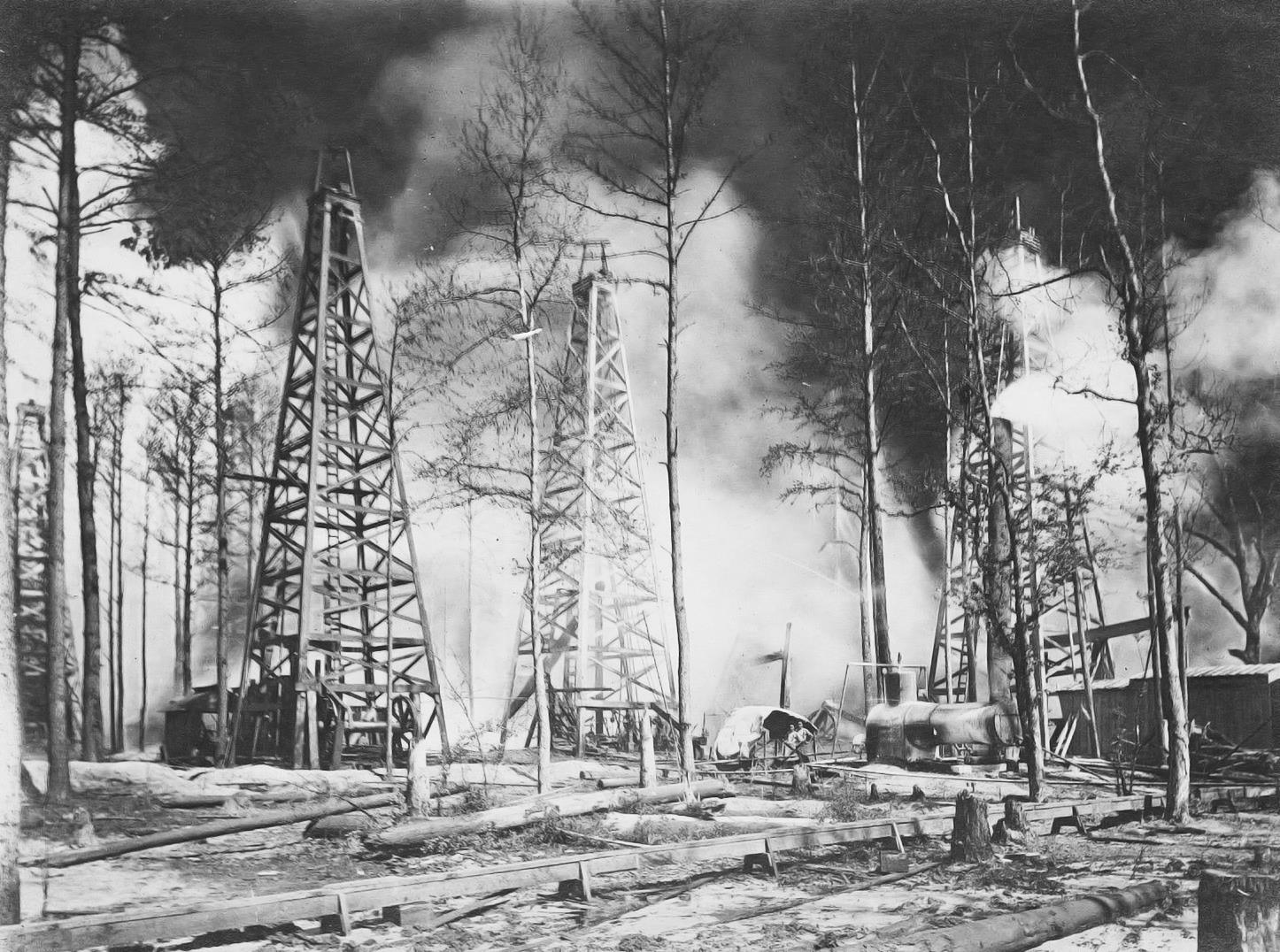

New companies rush to drill at Spindletop Hill in early 1900s.

When a geyser of oil erupted in 1901 on Spindletop Hill, near Beaumont, Texas, it launched the greatest oil boom in America — far exceeding the nation’s first commercial oil well in 1859.

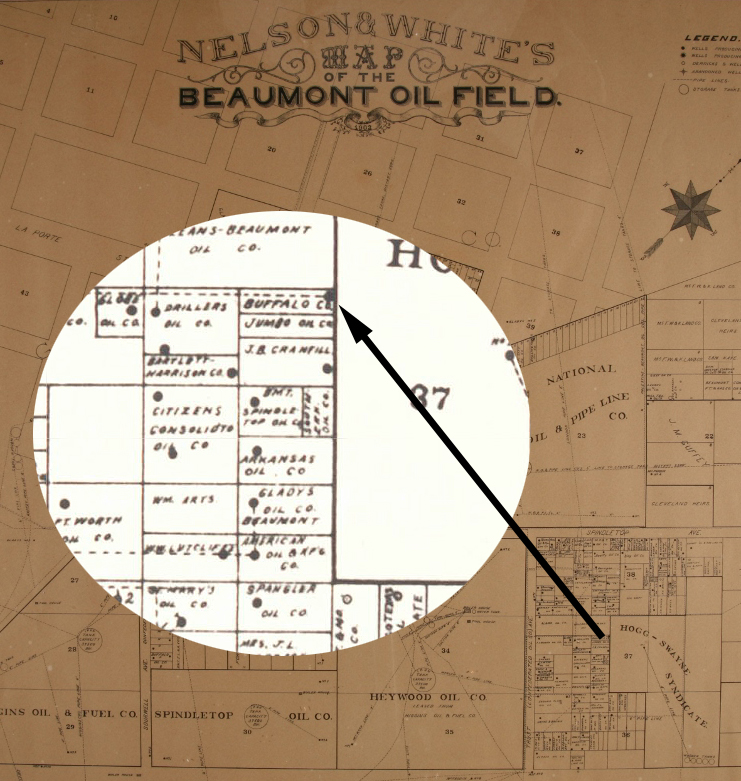

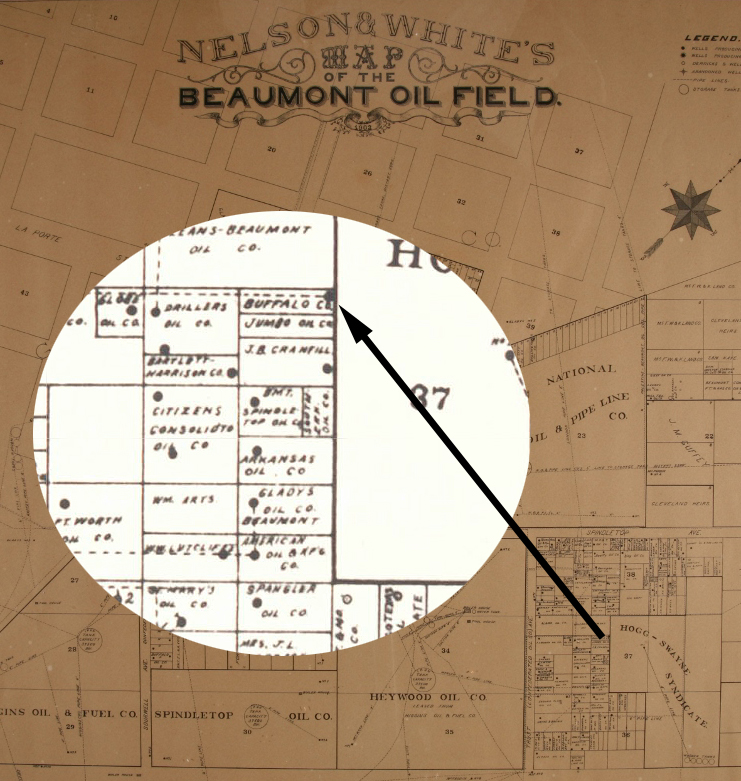

Many new and inexperienced oil ventures were formed almost overnight, including Buffalo Oil Company. The Spindletop field produced 43 million barrels of oil in its first four years, helping to launch the modern petroleum industry.

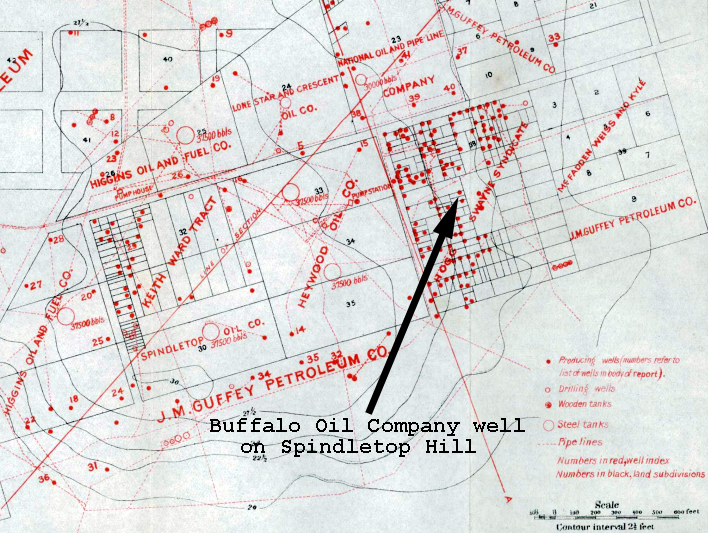

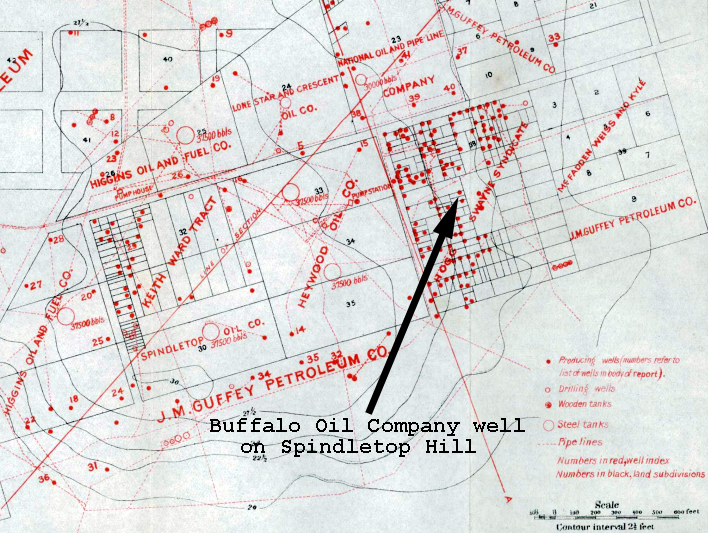

Among the 280 wells at Spindletop in 1902, Buffalo Oil completed a producing oil well at a depth of 960 feet on a lease of only 1/32 of an acre.

Buffalo Oil Company had quickly formed with $300,000 capitalization and stock listed with par value of 10 cents. Encouraged by the first well’s success, speculators invested in the company’s second. But by May 1902 the second Buffalo Oil well was “dry and abandoned” after reaching 1,400 feet deep.

As at least one expert noted at the time, the average life of flowing wells was short, “frequently but a few weeks and rarely more than a few months, with constantly diminishing output.”

Meanwhile, competing companies drove up the cost of drilling equipment and leases. Spindletop Hill was crowded with wooden derricks, oil storage tanks, and roughnecks.

Batson Oiflield

With signs of Spindletop production dropping, Buffalo Oil shifted operations to nearby Batson, where a 1903 well drilled by W.L. Douglas’ Paraffine Oil Company produced 600 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 790 feet. But the exploration company’s luck did not improve.

Map with detail showing Buffalo Oil Company lease among other drilling companies at Beaumont, Texas, home of a giant oilfield discovered in 1901.

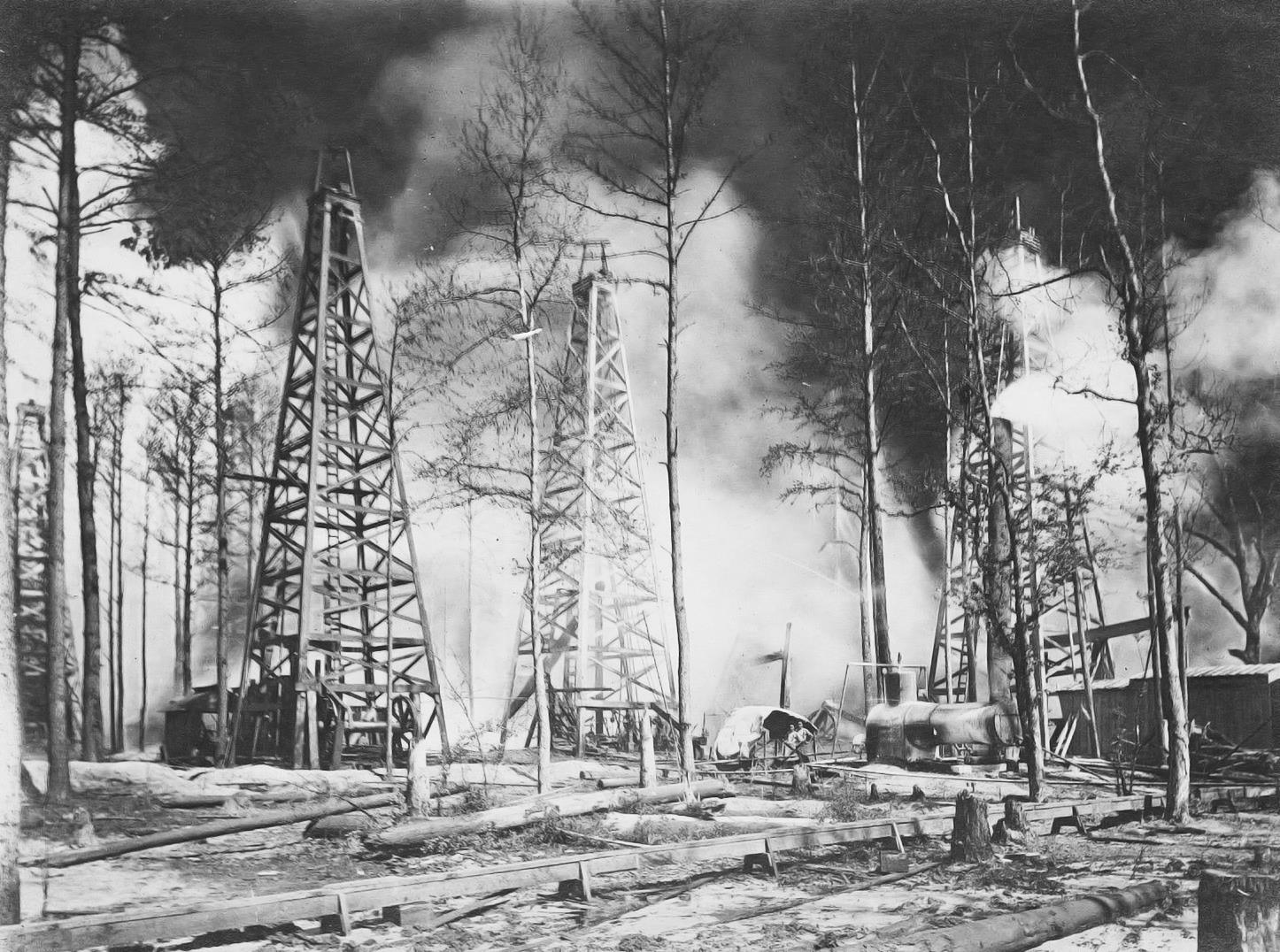

As the Batson field reached its peak monthly production of 2.6 million barrels of oil, a fire swept through the crowded oilfield.

“The fire burned furiously for several hours and though there were no fire appliances on the field, it is doubtless if equipment could have been used owing to the intense heat generated by the flames,” noted the Petroleum Review and Mining News.

Buffalo Oil Company’s well, derrick and equipment were completely destroyed.

Often caused by lightening strikes, oil tank fires were sometimes fought using cannons (learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires). After the Batson fire, the annual Buffalo Oil Company stockholder’s meeting took place in April 1904.

Fire engulfed the Batson oilfield in 1902, destroying the equipment and future of Buffalo Oil Company. Photo courtesy Traces of Texas.

“The company states that their recent investment at Batson so far has proved a serious loss to them, and the present outlook is very unfavorable,” reported the Petroleum Review and Mining News. But it got even worse.

Two weeks after the dire report to share owners, a second Batson fire destroyed another Buffalo Oil producing well and two 1,200-barrel storage tanks. Petroleum Review and Mining News concluded the fire “probably originated through an explosion in the pumping plant.”

The Batson oilfield would continue to produce for many years, but without Buffalo Oil Company. As late as 1993 the field yielded almost 200 barrels of oil a day, but Buffalo Oil was history without having paid a dividend.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Buffalo Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/buffalo-oil-company. Last Updated: October 31, 2023. Original Published Date: October 28, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 20, 2023 | Petroleum History Almanac

Researching her family’s distant connection to the U.S. oil patch, Marianne Jans of the the Netherlands discovered the American Oil & Gas Historical Society website. She hopes visitors to the site’s Petroleum History Research Forum might help add to her limited information about a great-great uncle who worked in Texas oilfields. He apparently was as a driller from the 1920s until the early 1930s.

Although details are scarce, Jans seeks news about her great-great uncle Ralph “Dutch” Weges — who in 1962 reportedly returned to the Netherlands by ship. His petroleum-related career included serving on merchant vessels.

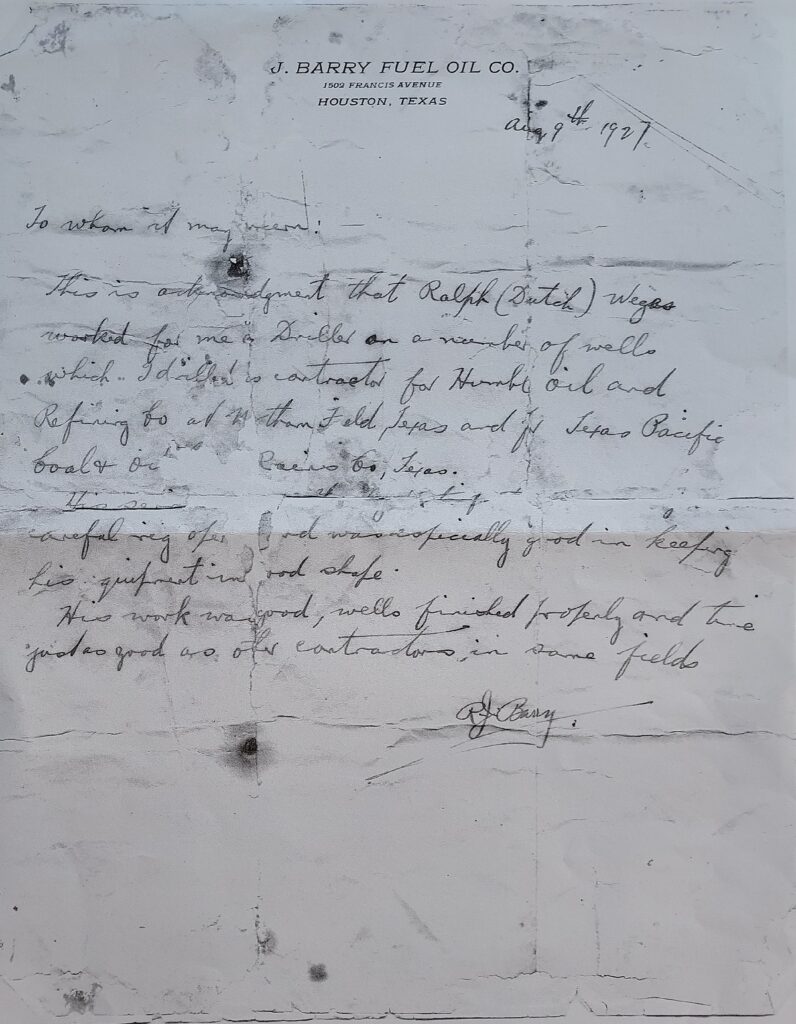

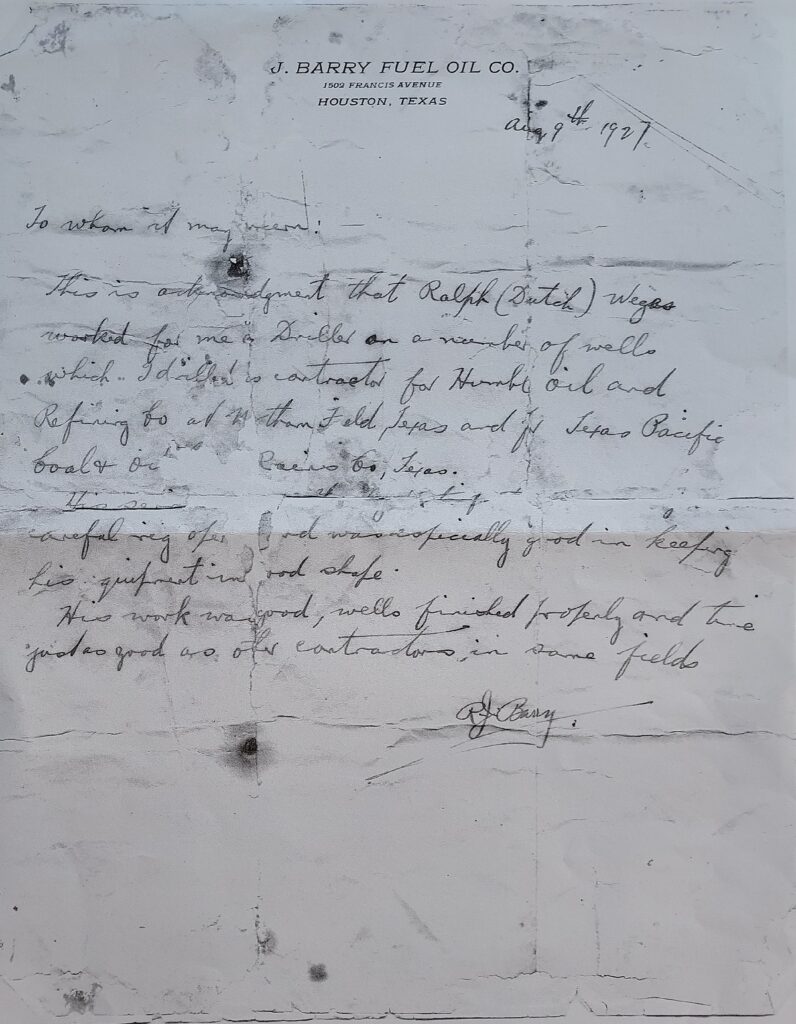

Regarding his work in Texas, she has a 1927 letter of recommendation with some clues.

Marianne Jans’ scan of the August 1927 Barry Fuel Oil Company’s letter of recommendation for her great-great uncle, Ralph Weges.

“In papers he left behind, he also had a recommendation from his employer in 1927,” according to Jans. “J. Barry Fuel Oil Co. is not in your list of historic companies, so I am sending this document.” she added.

Transcription of the great-great uncle’s letter, dated August 9, 1927:

J. Barry Fuel Oil Co.

1501 Francis Avenue

Houston, Texas

Aug 9th 1927

To whom it may concern:

This is acknowledgement that Ralph (Dutch) Weges

worked for me [&] Drilled on a number of wells

which I drilled as contractor for Humble Oil and

Refining [unreadable] Northern Field, Texas and [for] Texas Pacific

Coal & Oil [unreadable] Co, Texas.

His [unreadable] careful rig [unreadable] and was specifically good in keeping

his equipment in good shape.

His work was good, wells finished properly and time

just as good as other contractors in same fields.

RJ Barry

Not finding more information about the J. Barry Fuel Oil Company, Jans learned more about the two well-documented companies J. Barry worked with as a drilling contractor.

Humble Oil and Refining Company (now ExxonMobil) was founded in 1917. The company, which would discover many oilfields, in 1933 signed an historic lease with the King Ranch. The other company referenced in the letter was the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

In addition, Ralph Weges had other connections with the U.S. petroleum industry, according to Jan’s research. Her great-great uncle traveled overseas aboard the SS La Campine in September 1916.

Launched in 1889, La Campine was an early transatlantic oil tanker owned by the American Petroleum Company of Rotterdam and later by an Esso subsidiary in Belgium (it was sunk by a German submarine during World War I).

“What surprised me, was that Ralph Weges was anyway on board two ships that transported cargo for Esso, now Exxon Mobile,” Jans noted. “So he already worked for a petroleum/oil company on these ships. First as a 2nd cook and later petty officer. Two other vessels, the Anacortes and the SS Vigo, I must research further.”

As her investigation into family history continues from the Netherlands, Marianne Jans seeks information about her great-great uncle’s overseas career, the J. Barry Fuel Oil Company, and his role in Texas oilfields,

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Driller from Netherlands.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/driller-from-netherlands. Last Updated: February 10, 2024. Original Published Date: October 24, 2023.

(1976); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(2014). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.