Sour Lake produces Texaco

As drillers and speculators rushed to Spindletop Hill, the Texas Company was organized in 1902.

A series of oil and natural gas discoveries at Sour Lake, Texas — near the famous 1901 gusher at Beaumont — helped launch the major oil company Texaco.

Originally known as Sour Lake Springs because of sulfurous spring water popular for its healing properties, a series of oil discoveries brought wealth and new petroleum companies to Hardin County in southeastern Texas.

“A forest of oil well derricks at Sour Lake, Texas,” circa early1900s, courtesy the W.D. Hornaday Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin. Oil discoveries at the resort town northwest of the world-famous 1901 Spindletop gusher transformed the Texas Company into Texaco.

As the science of petroleum exploration and production evolved, some geologists predicted oil was trapped at a salt dome at Sour Lake, similar to that of Beaumont’s Spindletop Hill formation, which was producing massive amounts of oil.

According to Charles Warner in Texas Oil & Gas Since 1543, in November 1901 an exploratory well found “hot salt water impregnated with sulfur between 800 and 850 feet…and four oil sands about 10 feet thick at a depth of approximately 1,040 feet.”

Warner noted that the Sour Lake Springs field’s discovery well came four months later when a second attempt by the Great Western Company drilled “north of the old hotel building” in the vicinity of earlier shallow wells.

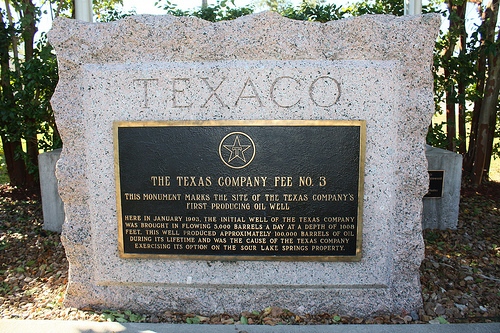

A monument marks the site where in 1903 the Fee No. 3 well flowed at 5,000 barrels of oil a day, launching the Texas Company into becoming Texaco.

“This well secured gusher production at a depth of approximately 683 feet on March 7, 1902,” Warner reported. “The well penetrated 40 feet of oil sand. The flow of oil was accompanied by a considerable amount of loose sand, and it was necessary to close the well in from time to time and bail out the sand, after which the well would respond with excellent flows.”

As more discoveries followed, Joseph “Buckskin Joe” Cullinan and Arnold Schlaet were among those who rushed to the area from their offices in Beaumont.

The Texas Company

The most significant company that started during the Spindletop oil boom was The Texas Company, according to historian Elton Gish.

“Cullinan worked in the Pennsylvania oil industry and later went to Corsicana, Texas, about 1898 when oil was first discovered in that district, where he became the most prosperous operator in the field,” reported Gish in his “History of the Texas Company and Port Arthur Works Refinery.”

Cullinan formed the Petroleum Iron Works, building oil storage tanks in the Beaumont area — where he was introduced to Schlaet. “When the Spindletop boom came in January 1901, Mr. Cullinan decided to visit Beaumont,” Gish noted. Schlaet managed the oil business of two brothers, New York leather merchants.

Named after its New York City telegraph address, the Texaco brand became official in 1959. Postcard of a Texaco service station next to a cafe in Kingman, Arizona.

“Schlaet’s field superintendent, Charles Miller, traveled to Beaumont in 1901 to witness the Spindletop activity and met with Cullinan, whom he knew from the oil business in Pennsylvania. He liked Cullinan’s plans and asked Schlaet to join them in Beaumont.”

According to Texaco, Cullinan and Schlaet formed the Texas Company on April 7, 1902, by absorbing the Texas Fuel Company and inheriting its office in Beaumont. Texas Fuel had organized just one year earlier to purchase Spindletop oil, develop storage and transportation networks, and sell the oil to northern refineries.

By November 1902, the new Texas Company was establishing a new refinery in Port Arthur as well as 20 storage tanks, building its first marine vessel, and equipping an oil terminal to serve sugar plantations along the Mississippi River.

Fee No. 3 Discovery

The Texas Company struck oil at Sour Lake Springs in January 1903, “after gambling its future on the site’s drilling rights,” the company explained. “The discovery, during a heavy downpour near Sour Lake’s mineral springs, turned the company into a major oil producer overnight, validating the risk-taking insight of company co-founder J.S. Cullinan and the ability of driller Walter Sharp.”

A Texaco station was among the 2012 indoor exhibits featured at the National Route 66 Museum in Elk City, Oklahoma. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Their 1903 Hardin County discovery at Sour Lake Springs — the Fee No. 3 well — flowed at 5,000 barrels a day, securing the Texas Company’s success in petroleum exploration, production, transportation, and refining. Sharp founded the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in 1908 with Howard Hughes Sr.

High oil production levels from the Sour Lake field and other successful wells in the Humble oilfield (1905) secured the company’s financial base, according to L. W. Kemp and Cherie Voris in the Handbook of Texas Online.

“In 1905 the Texas Company linked these two fields by pipelines to Port Arthur, ninety miles away, and built its first refinery there. That same year the company acquired an asphalt refinery at nearby Port Neches,” the authors noted.

“In 1908 the company completed the ambitious venture of a pipeline from the Glenn Pool, in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), to its Southeast Texas refineries,” added Kemp and Voris.

Telegraph Address: Texaco

As early as 1905, the Texas Company had established marketing facilities not only throughout the United States but also in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Panama.

The telegraph address for the company’s New York office is “Texaco” — a name soon applied to its products. The company registered its first trademark, the original red star with a green capital letter “T” superimposed on it in 1909. The letter remained an essential component of the logo for decades.

In August 1926, the Texas Corporation incorporated in Delaware (from Texas) and by an exchange of shares acquired outstanding stock of The Texas Company, which was dissolved the next year.

The new corporation became the parent company of numerous “Texas Company” — Texaco — entities and other subsidiaries, according to Jim Hinds of Columbus, Indiana (see Histories of Indian Refining, Havoline, and Texaco). By 1928, Texaco operated more than 4,000 gasoline stations in 48 states. It already was a major oil company when it officially renamed itself Texaco in 1959.

1987 Bankruptcy

Texaco lost a 1985 court battle following its purchase of Getty Oil Company. In February 1987 a Texas court upheld the decision against Texaco for having initiated an illegal takeover of Getty Oil after Pennzoil had made a bid for the company. Texaco filed for bankruptcy in April 1987.

The companies settled their historic $10.3 billion legal battle for $3 billion when Pennzoil agreed to drop its demand for interest. The Los Angeles Times reported the compromise was vital for Texaco emerging from bankruptcy, a haven sought to stop Pennzoil from enforcing the largest court judgment ever awarded at the time.

On October 9, 2001, Chevron and Texaco agreed to a merger that created ChevronTexaco — renamed Chevron in 2005. Although the Sour Lake Springs oil boom was surpassed by other Texas discoveries, it has remained the birthplace of Texaco.

Learn more about southeastern Texas petroleum history in Spindletop creates Modern Petroleum Industry and Prophet of Spindletop.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Texaco Story, The First Fifty Years 1902 – 1952 by Texas Company (1952). Texaco’s Port Arthur Works, A Legacy of Spindletop and Sour Lake (2003); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support AOGHS to help maintain this energy education website, a monthly email newsletter, This Week in Oil and Gas History News, and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Sour Lake produces Texaco.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/sour-lake-produces-texaco. Last Updated: February 28, 2026. Original Published Date: April 5, 2014.