Ironing with Gasoline

“Self-Heating Sad Irons” patented in 1903 used gasoline to make ironing easier.

On ironing day long before electricity, a row of sad irons could be found in the kitchen where the family’s cast-iron cook stove kept them hot. Three or four of these heavy “sadirons” — from the old English word meaning “solid” — cycled between the stove and a nearby ironing board.

With each sad iron weighing five to nine pounds, smoothing clothes led to an exhausting ironing routine. In 1872, Mary Florence Potts from Ottumwa, Iowa, patented a sad iron design with two pointed ends and a quick-change detachable walnut handle.

The 19-year-old housewife’s invention offered relief from blistered palms and was instantly popular nationwide. Thirty years later, a Civil War veteran brought another innovation to ironing.

Gasoline-fueled Sad Iron

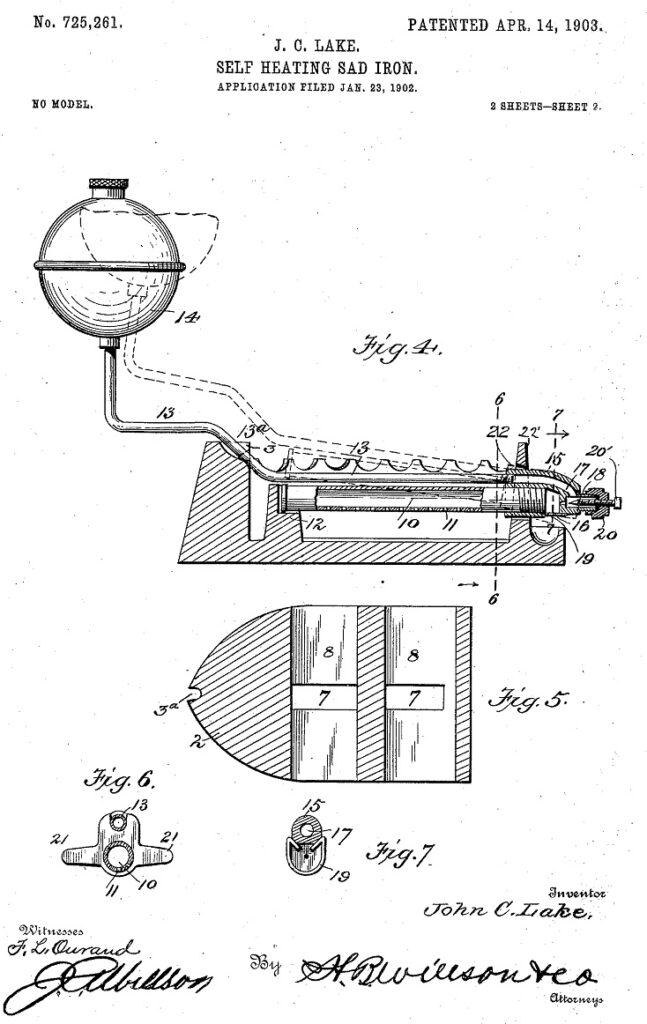

John C. Lake, who served in the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War, patented (No. 725,261) a gasoline-fueled “Self-Heating Sad Iron” in April 1903.

Lake’s invention made the family fortune and brought prosperity to Big Prairie, Ohio, where he established the Monitor Sad Iron Company on the Pennsylvania Railroad line. The manufacturing company in Amish country would make petroleum-fueled sad irons for the next 50 years.

The 61-year-old inventor earlier had shared three woodworking tool patents with his father Abraham, but none led to production. Lake’s new gasoline-fired sad iron would bring easier ironing to households without electrical service, which in 1903 meant most of America.

As advertised, “Monitor Self-Heating Sad Irons” did not need the kitchen stove, maintained a steady temperature, and turned on and off with a knob. Two tablespoons of alcohol started the process and charged the reservoir delivery system.

“Save Half the Time, Half the Labor, and All the Worry of Laundry Day,” the ads proclaimed as consumers warmly welcomed the gasoline-fueled sad irons, which sold for $3.50 each.

Monitor Sad Iron Company expanded by licensing an army of sales agents. As the factory in Big Prairie grew, by 1920 the company could proclaim 850,000 in cumulative sales. In the 1930s, Monitor added a new brand (Royal) as Lake’s son Bertus received three patents for improvements.

Geologist Iron Man

Antique iron collector Prof. Kevin McCartney knows a lot about Monitor Sad Iron Company and its early competitors like Jubilee and Ideal. A professor of Geology at the University of Maine at Presque Isle, he also serves as director of the Northern Maine Museum of Science.

Since 2013, McCartney has posted more than 50 YouTube videos, “to educate and entertain the avid collector, antique shop owner, pickers and novices alike. Each video is a mini-lesson on a different topic about irons.”

In his Kevin Talks Irons number 54, “Firing up the 1903 Monitor gasoline iron,” he described how consumers preferred Monitor’s gasoline appliance — made with just three durable assemblies — because it was “simple, utilitarian, and economical.”

The Monitor Sad Iron Company’s patented self-heating design became “most common of the early gasoline irons.” Formerly a byproduct of kerosene refining, gasoline also had begun its transformation from “white gas” into an automobile fuel before Anti-Knock Ethyl and other additives added color.

Coleman Lamp Company entered the gasoline-fueled iron business in the 1920s. Based in Wichita, Kansas, Coleman began producing a self-heating iron while securing additional patents in 1940.

Products from Monitor, Coleman, Royal and others competed in catalog offerings and advertisements, especially for potential customers in rural, unelectrified regions. The self-heating appliances burned the basic white gas (naphtha). Coleman later branded and sold the fuel in one-gallon containers as Coleman Fuel.

Coleman Company quit manufacturing gasoline-fueled sad irons after World War II, and the Monitor Sad Iron factory closed in 1954 as electricity relegated most such artifacts to museums and antique shops.

When Mary Florence Potts originally patented her innovative sad iron (today commonly spelled sadiron), she used her name instead of Mrs. Joseph Potts, according to a 2021 “Out of the Attic” article by Julie Martineau of Des Moines County Historical Society (DMCHS).

______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ironing with Gasoline.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/ironing-with-gasoline. Last Updated: April 1, 2025. Original Published Date: November 5, 2022.