Carl Baker and Howard Hughes

The inventive founders of oilfield service company giants Baker Oil Tools and Hughes Tools.

As the U.S. petroleum industry expanded following the January 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill in Texas, service company pioneers like Carl Baker and Howard Hughes brought new technologies to oilfields.

Baker Oil Tools and Hughes Tools specialized in maximizing petroleum production, as did oilfield service company competitors Schlumberger, a French company founded in 1926, and Halliburton, which began in 1919 as a well-cementing company.

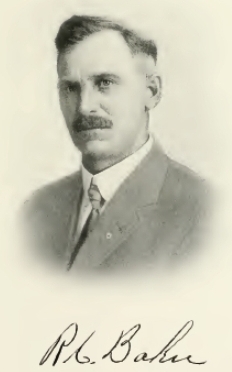

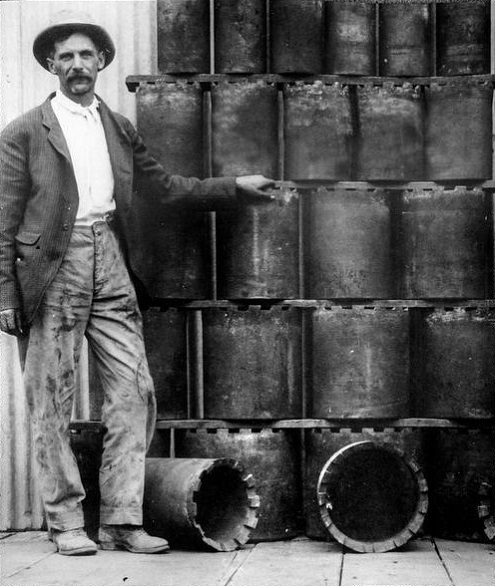

R.C. “Carl” Baker Sr.

Baker Oil Tool Company (later Baker International) had been founded by Reuben Carlton “Carl” Baker Sr., who among other inventions patented a cable-tool drill bit in 1903 after founding the Coalinga Oil Company in Coalinga, California.

The oil wells Carl Baker had drilled near Coalinga encountered hard rock formations that caused problems with casing, so he developed an offset cable-tool bit allowing him to drill a hole larger than the casing. He also patented a “Gas Trap for Oil Wells” in 1908, a “Pump-Plunger” in 1914, and a “Shoe Guide for Well Casings” in 1920.

Coalinga was “every inch a boom town and Mr. Baker would become a major player in the town’s growth,” according to the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum. He also organized several small oil companies and the local power company and established a bank.

After drilling wells in the Kern River oilfield, Baker added to his technological innovations on July 16, 1907, when he was awarded a patent for his Well Casing Shoe (No. 860,115), a device ensuring uninterrupted flow of oil through a well. His invention revolutionized oilfield production.

R.C. “Carl” Baker standing next to Baker Casing Shoes in 1914. Photo courtesy R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

In 1913, Baker organized the Baker Casing Shoe Company (renamed Baker Tools two years later). He opened his first manufacturing plant in Coalinga.

When Baker Tools headquarters moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, the building remained a company machine shop. It was donated by Baker to Coalinga in 1959. Two years later, the original machine shop and office of Baker Casing Shoe reopened as the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

By the time Carl Baker Sr. died in 1957 at age 85, he had been awarded more than 150 U.S. patents in his lifetime. “Though Mr. Baker never advanced beyond the third grade, he possessed an incredible understanding of mechanical and hydraulic systems,” reported the former Coalinga museum.

Baker Tools became Baker International in 1976 and Baker Hughes after the 1987 merger with Hughes Tool Company.

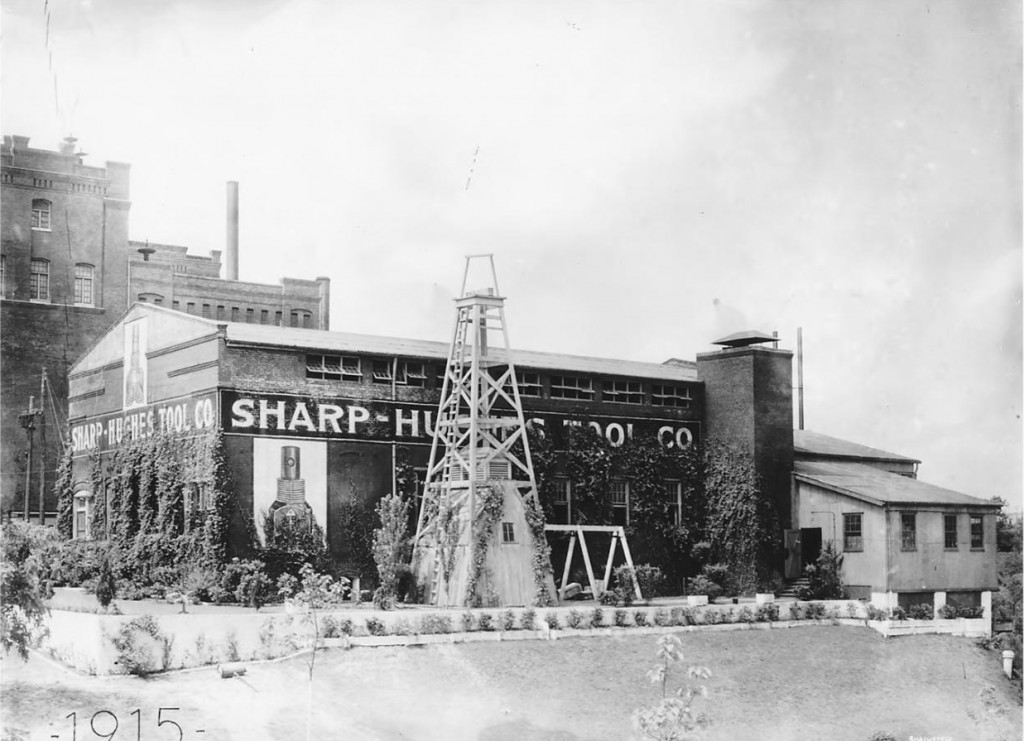

The Houston manufacturing operations of Sharp-Hughes Tool at 2nd and Girard Streets in 1915. The site is on the campus of the University of Houston–Downtown. Photo courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library.

Howard Hughes and Walter Sharp

The Hughes Tool Company began in 1908 as the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company, founded by Walter B. Sharp (1870–1912) and Howard R. Hughes, Sr.

Sharp was an experienced Texas oilfield pioneer who in 1893 drilled for the Gladys City Oil and Gas Manufacturing Company at Beaumont, Texas. The exploratory well on Spindletop Hill did not find oil, but it helped lead to the giant oilfield’s discovery in 1901, according to Texas State Historical Association (TSHA).

In 1896, Sharp was one of the drillers at Corsicana when the state’s first commercial oilfield was developed. While there, he met Joseph “J.S.” Cullinan, who became a lifelong friend. Cullinan in 1902 founded the Texas Company (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

Sharp and Hughes in 1907 drilled test wells at Goose Creek/ “When both wells had to be abandoned because of the hard rock encountered, the two men began to consider the possibility of developing a roller rock bit. It was eventually arranged for Hughes to proceed with the designing and construction of a bit, with capital provided equally by Sharp and Cullinan.

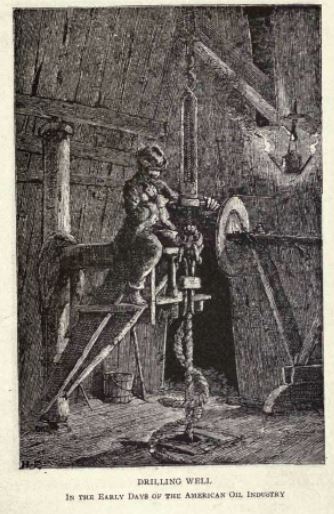

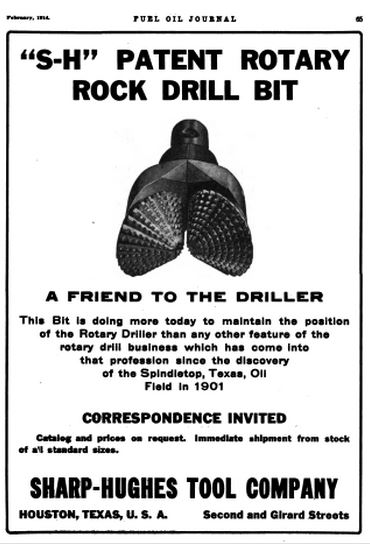

Rotary drilling bits shaped like fishtails became obsolete in 1909 when the two inventors introduced a dual-cone roller bit. They created a bit “designed to enable rotary drilling in harder, deeper formations than was possible with earlier fishtail bits,” according to a Hughes historian. Secret tests took place on a drilling rig at Goose Creek, south of Houston.

Hard Rock at Goose Creek

“In the early morning hours of June 1, 1909, Howard Hughes Sr. packed a secret invention into the trunk of his car and drove off into the Texas plains,” noted Gwen Wright of History Detectives in 2006. The drilling site was near Galveston Bay. Rotary drilling “fishtail ” bits of the time were “nearly worthless when they hit hard rock.”

The new technology would soon bring faster and deeper drilling worldwide, helping to find previously unreachable oil and natural gas reserves. The dual-cone bit also created many Texas millionaires, explained Don Clutterbuck, one of the PBS show’s sources.

“When the Hughes twin-cones hit hard rock, they kept turning, their dozens of sharp teeth (166 on each cone) grinding through the hard stone,” he added.

Although several inventors tried to develop better rotary drill bit technologies, Sharp-Hughes Tool Company was the first to bring it to American oilfields. Drilling times fell dramatically, saving petroleum companies huge amounts of money.

Howard Hughes Sr. (1869 – 1924) on August 10, 1909, was awarded a U.S. patent for a dual-cone drill bit that could crush hard rock.

The Society of Petroleum Engineers has noted that about the same time Hughes developed his bit, Granville A. Humason of Shreveport, Louisiana, patented the first cross-roller rock bit, the forerunner of the Reed cross-roller bit.

Biographers have noted that Hughes met Granville Humason in a Shreveport bar, where Humason sold his roller bit rights to Hughes for $150. The University of Texas Center for American History Collection includes a 1951 recording of Humason talking about that chance meeting. He recalled spending $50 of his sale proceeds at the bar that evening.

After Walter Sharp died in 1912, his widow Estelle Sharp sold her 50 percent share in the company to Hughes. It became Hughes Tool in 1915. Despite legal action between Hughes Tool and the Reed Roller Bit Company in the late 1920s, Hughes prevailed and his oilfield service company prospered.

Hughes Tool

By 1934, Hughes Tool engineers designed and patented the three-cone roller bit, an enduring design that remains much the same today. Hughes’ exclusive patent lasted until 1951, which allowed his Texas company to grow worldwide. More innovations (and mergers) would follow.

A February 1914 advertisement for the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in Fuel Oil Journal.

Frank Christensen and George Christensen had developed the earliest diamond bit in 1941 and introduced diamond bits to oilfields in 1946, beginning with the Rangley field of Colorado. The long-lasting tungsten carbide tooth came into use in the early 1950s.

After Baker International acquired Hughes Tool Company in 1987, Baker Hughes acquired the Eastman Christensen Company three years later. Eastman was a world leader in directional drilling.

When Howard Hughes Sr. died in 1924, he left three-quarters of his company to Howard Hughes Jr., then a student at Rice University. The younger Hughes added to the success of Hughes Tool while becoming one of the richest men in the world. His many legacies include founding Hughes Aircraft Company and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Learn more in Making Hole – Drilling Technology.

Oilfield Service Competition

A major competitor for any energy service company, today’s Schlumberger Limited can trace its roots to Caen, France. In 1912, brothers Conrad and Marcel began making geophysical measurements that recorded a map of equipotential curves (similar to contour lines on a map). Using very basic equipment, their field experiments led to the invention of a downhole electronic “logging tool” in 1927.

After developing an electrical four-probe surface approach for mineral exploration, the brothers lowered another electric tool into a well. They recorded a single lateral-resistivity curve at fixed points in the well’s borehole and graphically plotted the results against depth – creating first electric well log of geologic formations.

Meanwhile, another service company in Oklahoma, the Reda Pump Company had been founded by Armais Arutunoff, a close friend of Frank Phillips. By 1938, an estimated two percent of all the oil produced in the United States with artificial lift, was lifted by an Arutunoff pump.

Learn more in Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump (also see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Carl Baker and Howard Hughes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/carl-baker-howard-hughes. Last Updated: July 17, 2025. Original Published Date: December 17, 2017.