The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes

How oilfield paraffin created Vaseline and Maybelline cosmetics.

Few associate 1860s oil wells with women’s eyes, but they are fashionably related. From paraffin to Vaseline, this is the story of how the goop that accumulated around the sucker rods of America’s earliest oil wells made its way to eyelashes.

In 1865, a 22-year-old Robert Chesebrough left the prolific oilfields of Pithole and Titusville, Pennsylvania, to return to his Brooklyn, New York, laboratory. He carried samples of a waxy substance that clogged wellheads. He already had dabbled in the “coal oil” business with experiments on refinery processes.

Robert Chesebrough will find a way to purify the waxy paraffin-like substance that clogged oil wells in early Pennsylvania petroleum fields. Photo courtesy Unilever Corp.

Chesebrough’s laboratory expertise included distilling cannel coal into kerosene (coal oil), a lamp fuel in high demand among consumers. He also knew of the process for refining crude oil into a better kerosene.

Thus, when Edwin L. Drake completed the first U.S. oil well in August 1859, Chesebrough was among those who rushed to Pennsylvania oilfields to make his fortune.

“Now commenced a scene of excitement beyond description,” reported Scientific American. “The Drake well was immediately thronged with visitors arriving from the surrounding country, and within two or three weeks thousands began to pour in from the neighboring States.”

Chesebrough was convinced he too could get rich from the “black gold” of Pennsylvania’s oilfields.

Oilfield Sucker Rod Wax

Amid the Venango County exploration and production chaos, the young chemist noted a waxy buildup often confounded drilling. This paraffin-like substance clogged the wellhead and drew curses from riggers who had to stop drilling to scrape it away.

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96. This early bottle is from the collection of the Drake Well Museum in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

The only virtue of this goopy oilfield “sucker rod wax” was as an immediately available first aid for the abrasions, burns, and other wounds routinely afflicting the crews.

Paraffin to Vaseline

Chesebrough abandoned his notion of drilling a gusher and returned to New York, where he worked in his laboratory to purify the troublesome sucker-rod wax, which he dubbed “petroleum jelly,” one of America’s earliest petroleum products.

By August 1865, Chesebrough had filed the first of several patents “for purifying petroleum or coal oils by filtration.”

The chemist experimented with the analgesic effects of his extract by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying the purified petroleum jelly. He also gave it to Brooklyn construction workers to treat their minor scratches and abrasions.

After refining oilfield wax, Chesebrough experimented by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying his petroleum balm.

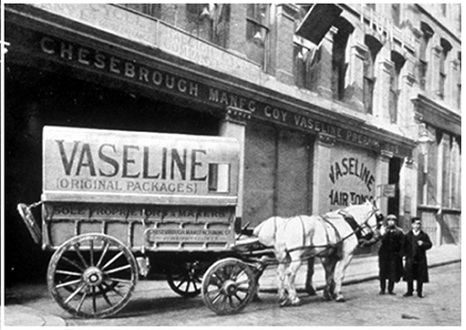

On June 4, 1872, Chesebrough patented a new product – “Vaseline.” His paraffin to Vaseline patent extolled the balm’s virtues as a leather treatment, lubricator, pomade, and balm for chapped hands. Chesebrough soon had a dozen wagons distributing the product around New York.

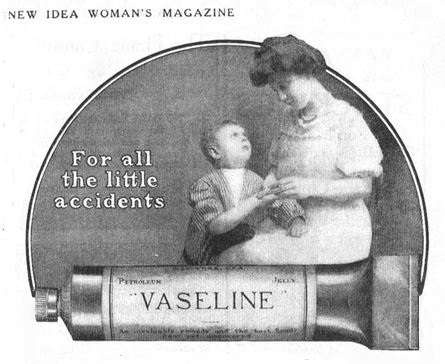

Customers used the “wonder jelly” creatively: treating cuts and bruises, removing stains from furniture, polishing wood surfaces, restoring leather, and preventing rust. Within 10 years, Americans were buying it at the rate of a jar a minute

Women had once used toothpicks to mix lamp black with Vaseline. By 1917, Tom Williams was selling premixed “Lash-Brow-Ine” by mail order. Photo courtesy Sharrie Williams.

An 1886 issue of Manufacture and Builder even reported, “French bakers are making large use of vaseline in cake and other pastry. Its advantage over lard or butter lies in the fact that, however stale the pastry may be, it will not become rancid.”

Flavor notwithstanding, Chesebrough himself consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day. He lived to be 96 years old. It was not long before thrifty young ladies found another use for Vaseline.

Mabel’s Eyelashes

As early as 1834, the popular book Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion suggested alternatives to the practice of darkening eyelashes with elderberry juice or a mixture of frankincense, resin, and mastic.

“By holding a saucer over the flame of a lamp or candle, enough ‘lamp black’ can be collected for applying to the lashes with a camel-hair brush,” the book advised.

Chesebrough’s female customers found that mixing lamp black with Vaseline using a toothpick made an impromptu mascara. Some sources claim that Miss Mabel Williams in 1913 employed just such a concoction preparing for a date. Williams was dating Chet Hewes.

Women were using Vaseline to make mascara by 1915. Cosmetic industry giant Maybelline traces its roots to the petroleum product. “What a Difference Maybelline Does Make” magazine ad from 1937.

Perhaps using coal dust or some other readily available darkening agent, she applied the mixture to her eyelashes for a date. Her brother, Thomas Lyle Williams, was intrigued by her method and decided to add Vaseline in the mixture, noted a Maybelline company historian.

Lash-Brow-Ine

A more reliable version of the story — told by Williams’ grandniece Sharrie Williams — has Mabel demonstrating “a secret of the harem” for her brother.

“In 1915, when a kitchen stove fire singed his sister Mabel’s lashes and brows, Tom Lyle Williams watched in fascination as she performed what she called ‘a secret of the harem’ mixing petroleum jelly with coal dust and ash from a burnt cork and applying it to her lashes and brows,” Sharrie Williams explained in her 2007 book, The Maybelline Story and the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It.

“Mabel’s simple beauty trick ignited Tom’s imagination and he started what would become a billion-dollar business,” concluded Williams.

Silent screen stars like Theda Bara, right, helped glamorize Maybelline mascara. By the 1930s, the paraffin to Vaseline to mascara concoction was available at five-and-dime stores for 10 cents a cake.

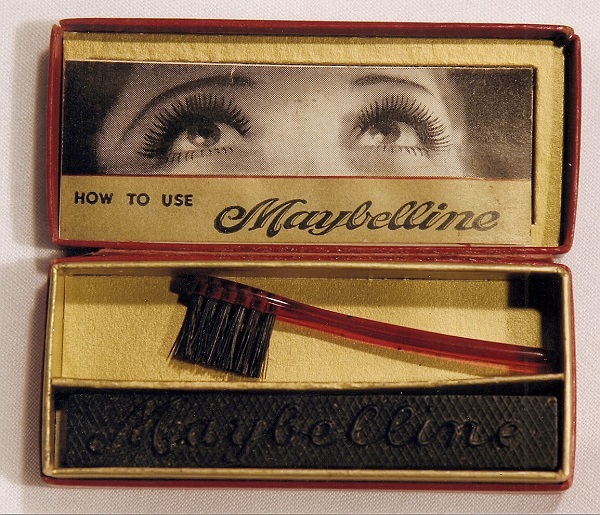

Inspired by his sister’s example, he began selling the mixture by catalog, calling it “Lash-Brow-Ine” (an apparent concession to the mascara’s Vaseline content). Women loved it.

When it became clear that Lash-Brow-Ine had potential, Williams, doing business in Chicago as Maybell Laboratories, on April 24, 1917, trademarked the name as a “preparation for stimulating the growth of eyebrows and eyelashes.”

Mail-Order Mascara

With sales exceeding $100,000 by 1920, Williams decided to rename the mascara Maybelline in honor of his sister, who worked with him in the Chicago office. Maybell Laboratories was renamed Maybelline in 1923 and concentrated on eye makeup. Mabel married Chet Hewes in 1926.

Whatever its petroleum product beginnings, Hollywood helped expand the Williams family cosmetics empire. The 1920s silent screen had brought new definitions to glamour. Theda Bara – an anagram for “Arab Death” – and Pola Negri, each with daring eye makeup, smoldered in packed theaters across the country.

Maybelline trumpeted its mail-order mascara in movie and confession magazines as well as Sunday newspaper supplements. Sales continued to climb. By the 1930s, Maybelline mascara was available at the local five-and-dime store for 10 cents a cake.

Both Vaseline, now part of Unilever, and Maybelline, later a subsidiary of L’Oréal, have continued as highly successful products, distantly removed from northwestern Pennsylvania’s “Wonder Jelly” introduced in 1870.

Special thanks to Linda Hughes, granddaughter of Mabel and Chet Hewes, who reviewed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s paraffin to Vaseline to Mascara article. She asked AOGHS to note that Mabel was very dedicated to her brother’s work –- and helped run the Maybelline company in Chicago.

Crayola Crayons

Paraffin from early U.S. oilfields also proved key to the phenomenal success of business partners Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith, who in 1891 patented an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.”

Soon, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed carbon black with oilfield paraffin to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker able to “stay on all” and named “Staonal,” still sold today. The company also manufactured a popular “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and a red, iron oxide barn paint.

By 1903, the Binney & Smith Company added color to paraffin for a new product, “Crayola” crayons. Learn more about their petroleum products in Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons. Oilfield paraffin also found its way into novelty candies like “wax lips.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/vaseline-maybelline-history. Last Updated: June 1, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2005.