by Bruce Wells | Apr 13, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

A state historical marker near Saginaw commemorates the birth of Michigan’s petroleum industry in 1925. E. Brown Oil Development Company would drill nearby five years later. The marker notes the Mt. Pleasant field, “helped make Michigan one of the leading oil producers of the eastern United States” and that Mount Pleasant became known as the “Oil Capital of Michigan.”

E. Brown Oil Development of Midland in April 1930 reportedly secured a lease about six miles northeast of Saginaw and drilled a well. Another well, the Grubb No. 2, was drilled in Isabella County, Chippewa Township (NE¼ of the NW¼ of the SW¼ of Section 2, Township 15 North, Range 4 West), according to Public Land Survey System online maps.

As wells drilled into the prolific Mt. Pleasant field reached 162 in June, E. Brown Oil Development reported completing a producer at 3,594 feet deep with initial production of 300 barrels of oil in 12 hours. In September, the company’s Grubb No. 3 well produced 325 barrels of oil an hour.

“Michigan Oil & Gas History,” a 2005 Clarke Historical Library exhibit at Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant.

By October 1931, E. Brown Oil Development’s earlier successes helped fund drilling of its No. 1 Homer Campbell well (in the center of the NE¼ of the NE¼ of Section 35, Township 14 North, Range 3 West). At depth of 1,360 feet, the well struck a 600,000 cubic foot initial flow of natural gas.

Two years later, E. Brown Oil Development expanded its search for 100 miles east to Sanilac County, at the base of a Michigan map’s “thumb.” It leased 160 acres from William Herdell in Sanilac County and began to drill on October 3, 1933. The well was sited in Argyle Township (SW¼ of the SW¼ of the SW¼ of Section 15, Township 13 North, Range 13 East).

But at a time when about 90 percent of U.S. exploratory wells ended as expensive failures, E. Brown Oil Development drilled a 2,353-foot-deep dry hole on November 4, 1933. The well was plugged and abandoned.

What happened to E. Brown Oil Development after that is a mystery, but in 1931 oil prices had dipped to a 13-year low of about $10 per barrel (in 2013 dollars) and Great Depression unemployment reached almost 25 percent.

Faced with low oil prices in a highly competitive industry, many oil companies failed and disappeared, leaving investors with stock certificates now only valued by collectors. E. Brown Oil Development appears to be among them. Today the state has several productive oil and natural gas fields, and Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant preserves Michigan Petroleum History.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

Prior to becoming an aspiring Kansas oilman, William Seyler wrote a book admonishing others about speculating in the petroleum industry. Then he started his own oil company.

Seyler was a self-proclaimed capitalist and investment expert who in 1919 published Danger Signals – A Key to Investing Money to Make Money.

His book (today available free online) offered several chapters about America’s rapidly expanding petroleum industry, including chapter 12, “Oil Land Get-Rich-Quick Schemes.”

Seyler advised potential investors to be wary. “The alluring possibilities of the oil business is, at this very writing, causing so many inexperienced men to engage in the promotion of wild-cat oil companies that haven’t the remotest chance to succeed,” he proclaimed. “Experience and constant practice alone make experts in judging the soundness of stocks and securities; of this there is no doubt.”

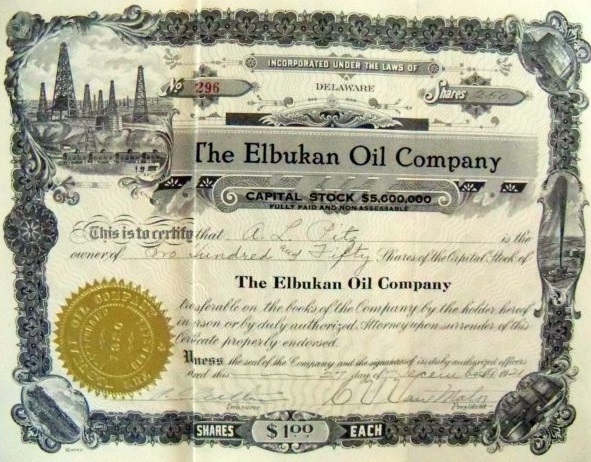

Within a year of publishing his book of investment advice, Seyler incorporated Elbukan Oil Company in Delaware (June 5, 1920). He began operations in El Dorado, Kansas, where the Stapleton No. 1 well of 1915 had launched a major Kansas Oil Boom.

His company was initially capitalized at $750,000 with par value assigned at $1 per share. But by March 1921 Elbukan Oil had increased its capital stock to $1.5 million to fund acquisition of more properties in the prolific Mid-Continent field.

The company successfully completed its Millheisler No. 5 well, which produced 100 barrels of oil northeast of El Dorado. Although production declined to 50 barrels a day, the success enabled the company to drill another well, the Millheisler No. 6, on the same 40-acre lease.

By December 31, 1921, Elbukan Oil Company had sold approximately $1.6 million of stock to investors nationwide, apparently including a large number from Wisconsin.

Seemingly prospering, the company owned a number of leases and pipelines in Kansas and Oklahoma. By 1923 it was producing and selling oil and natural gas. Then questions were raised about its accounting practices.

Elbukan Oil was prohibited from selling its stock in Wisconsin and Indiana, “as a result of continued delays by the Seyler company in presenting the semiannual audit of the financial conditions require by the state commission of all companies selling stock.”

The company’s difficulties compounded when it was alleged in court that Seyler had set up his company’s $120,000 purchase of a well valued at only $6,000. The deal included Elbukan Oil paying him personally $42,500 in cash and stock.

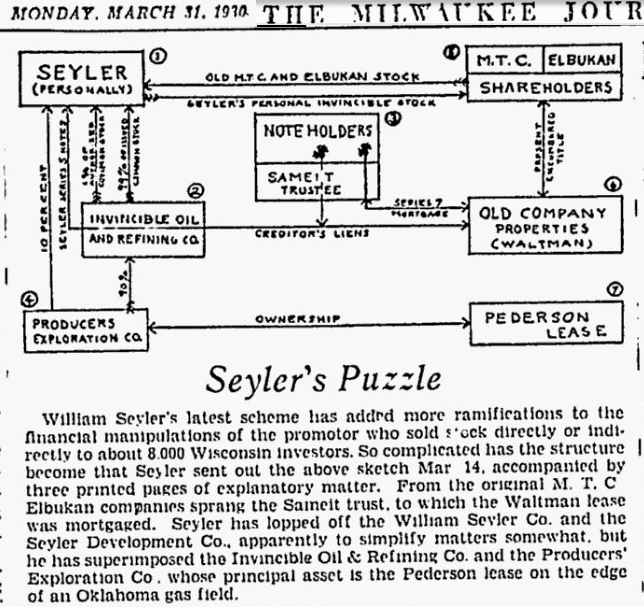

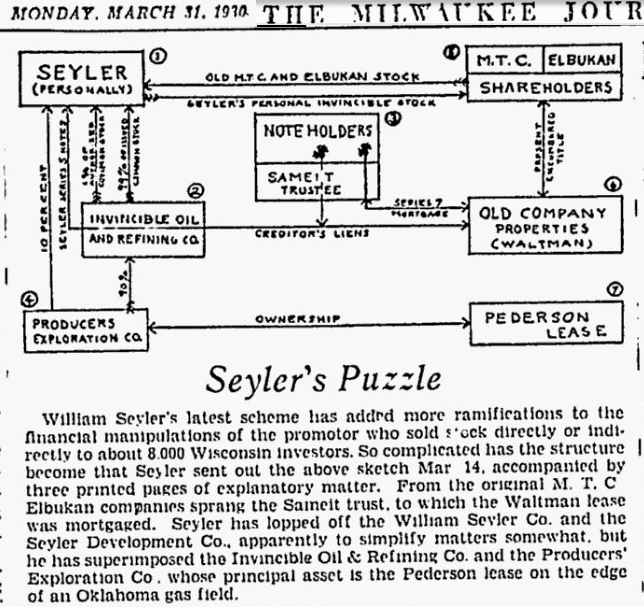

The U.S. District Court ultimately appointed receivers to manage Elbukan Oil assets as extended litigation followed. Undeterred, Seyler returned in 1930 – only to have the Milwaukee Journal report expose “William Seyler’s latest scheme.”

The Wisconsin newspaper illustrated Seyler’s intricate structure of company ownership, liens, properties, mortgages and stockholders. “Seyler’s Puzzle” appeared in a March 31, 1930, article.

Although Elbukan Oil Company stock was worthless by 1932, Seyler was not finished. He returned to Wisconsin investors one last time five years later, according to the Milwaukee Journal.

“Seyler, Oil Promoter, Again is Active Here,” the newspaper noted on April 15, 1937, adding that the investment adviser turned oilman was back “with a brand new scheme.” Editors again cautioned readers: “State authorities say Seyler and his many associates at one time took in $3,200,000 from about 9,000 Wisconsin residents.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of other companies and attempts to join highly speculative petroleum exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

___________________________________________________________________________________

Please support the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and this website with a donation.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

By the beginning of the 20th century, Texas wildcatters had fruitlessly pursued oil between Abilene and Fort Worth. They drilled mostly dry holes until 1917 when a gusher brought thousands to the arid region of cattle, cotton and mesquite trees.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Texas wildcatters had fruitlessly pursued oil between Abilene and Fort Worth. They drilled mostly dry holes until 1917 when a gusher brought thousands to the arid region of cattle, cotton and mesquite trees.

In October 1917, the McClesky No. 1 well in Eastland County revealed a massive oil-bearing sand 3,432 feet deep. The “Roaring Ranger” discovery made headlines worldwide just six months after America’s entry into World War I.

A find in nearby Desdemona soon added to North Texas oil discoveries. “The tiny peanut-farming hamlet of Desdemona in Eastland County was transformed when oil was struck in 1918,” noted one Texas historian. “Tents and shacks sprang up all around the town to house speculators and workers who flocked to the area.”

Located along Hog Creek, Desdemona (once called Hogtown) and the Ranger oilfield attracted new companies, some with little or no oil-patch experience. Among many others, the Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company profited by enthusiastically advertising stock sales to unwary investors.

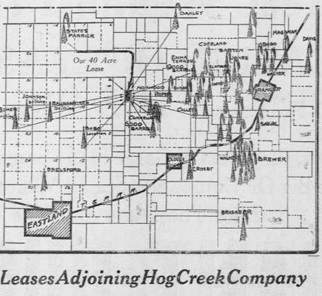

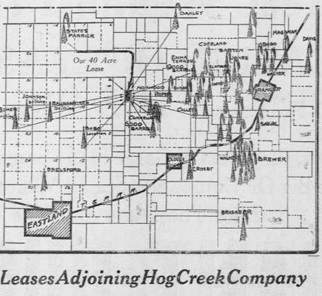

A detail from one of Ranger-Rock Island Oil and Refining’s circa 1920 newspaper ads (see below).

Ranger-Rock Island Oil and Refining

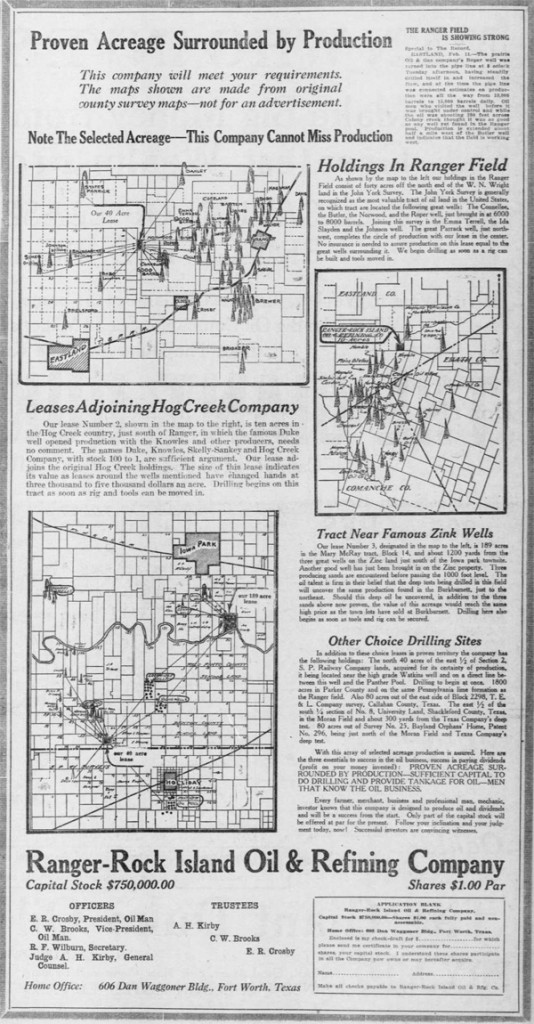

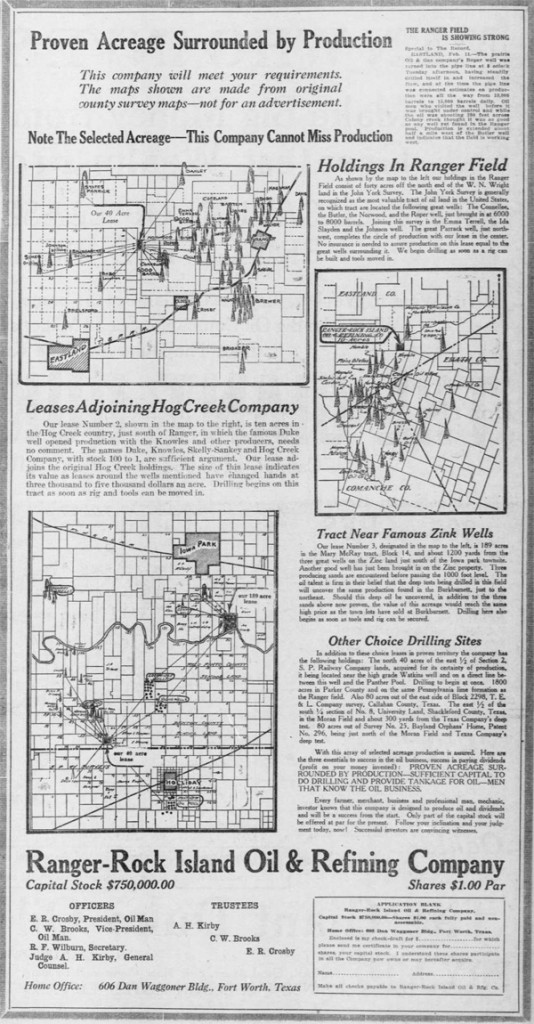

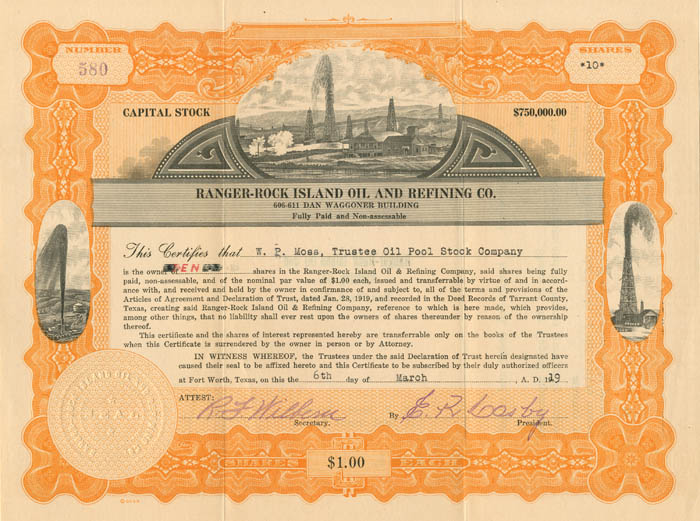

Eager to drill in the Ranger oilfield, E.R. Crosby, C.W. Brooks and A.H. Kirby formed the Ranger-Rock Island Oil & Refining Company in Fort Worth, Texas. With Crosby named president, the company was capitalized at $750,000.

By February 1919, half-page advertisements in the El Paso Herald solicited investors, noting the company’s leases were in close proximity to proven oil-producing wells.

“Every farmer, merchant, business and professional man, mechanic, and investor knows that this company is designed to produce oil and dividends and will be a success from the start,” declared the company’s newspaper ads.

A map illustrated proposed drill sites. “Note The Selected Acreage – This Company Cannot Miss Production,” the company crowed about its 40-acre lease northeast of Eastland. The ad included a convenient cut-out application to send with a check for purchasing stock at $1 per share.

Another map depicted Ranger-Rock Island Oil’ and Refining’s second lease south of Ranger – “in the Hog Creek country” – declaring that “drilling begins on this tract as soon as rig and tools can be moved in.”

Success came west of Fort Worth when Ranger-Rock Island Oil and Refining’s Wright No. 1 well reached 3,483 feet into the McClesky sand (by September 8, 1919, daily production was 3,000 barrels of oil). Then the Wright No. 2 well was completed for 2,700 barrels a day. Another oil strike soon followed.

“The headliner of the Ranger pool, the W.W. Wright No. 3 of the Ranger-Rock Island Oil [and Refining] Company came in with an initial flow 1,700 barrels of oil at around the 3,500 foot level,” noted the Oil & Gas News. “This is the third producing well brought in by that company.”

By April 1920, Ranger-Rock Island Oil and Refining had drilled three successive producing wells, but total production had dropped from an initial 8,000 barrels a day to only 1,400 barrels a day. The Ranger oilfield was being depleted by overproduction and the company was feeling it. As drilling and production costs rose, oil prices fell from about $3 a barrel at the beginning of 1920 to less than $1.75 by the end of the year.

By 1921, Oil Distribution News reported that Ranger-Rock Island Oil and Refining shares, originally sold at one dollar each, were being bid at 50 cents per share by stock traders. After investor litigation in 1924, the company disappeared from financial records.

Among others also seeking riches in the Ranger oilfield was a young World War I veteran, Conrad Hilton. Witnessing roughnecks waiting in line at an Eastland County motel convinced him to purchase what became the first Hilton Hotel.

Read about another North Texas discovery, the 1911 April Fool’s day oil gusher near Electra, Texas, that would help earn that town the title of “Pump Jack Capital of Texas.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of other attempts to join petroleum exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

Please support the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and this website with a donation.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 29, 2015 | Petroleum Companies

Southern Rose Oil & Gas Company incorporated on April 17, 1920, in Arkansas. By the end of June 1921, the company had secured a 25-acre site to build a refinery near El Dorado.

The company planned on using the “Edwards System of Refining Petroleum” reportedly perfected by Dr. E.A. Edwards, who had been termed the dean of refiners.

Southern Rose Oil & Gas then looked to Texas’ Mexia oilfield to drill its own oil wells to supply its refinery. The Mexia field in northwestern Limestone County, Texas, later introduced the concept of fault-line production in the Woodbine sands, notes the Handbook of Texas Online.

The Mexia field had begun producing oil moderately in 1920, but in August 1921, Western Oil Corporation’s Desenberg No. 1 well blew in at 18,000 barrels of oil a day, followed by the Adamson No. 1 well with 24,000 barrels of oil a day.

City historians later noted, “Little wonder that all roads led to Mexia and that they were jammed.”

The United States Investor of October 1, 1921, noted a variety of offers proposing Southern Rose Oil & Gas share owners exchange their stock for shares of Manhattan-Texas Petroleum Company, Manhattan Consolidated Petroleum Company, and/or Desdemona Oil & Refining Company.

Although such consolidations were not an uncommon effort to save under-capitalized ventures, investors had to be wary. “Neither the company itself or those companies, for the stock of which its stock is to be exchanged, have been receiving dividends,” noted U.S. Investor editors. “We are not favorably impressed with any of them as a medium of profit or investment either.”

On August 18, 1922, another company discovered oil in Mexia’s Kosse district (Jones No. 1 well). By November, Southern Rose Oil & Gas had a derrick of its own up with hopes to exploit the find.

The Jones No. 1 well however, “never fulfilled its initial promise and is still a text-book example of a one-well field,” according to the Handbook of Texas Online.

Southern Rose Oil & Gas Company’s well, the W.D. Allen No. 1, never progressed beyond construction of its derrick. To investors’ dismay, mounting debt ensured the demise of Southern Rose and loss of their investment. In May 1923, company assets were auctioned at an Eastland County, Texas, sheriff’s sale. Debt amounted to more than $24,500 ($342,000 in 2016 dollars) of which about half was recovered.

The first Arkansas oil gusher, the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well, blew in on January 10, 1921, near El Dorado and launched the Arkansas petroleum industry. By 1925 the 68-square-mile field led U.S. oil output – with production reaching 70 million barrels.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Oct 5, 2015 | Petroleum Companies

Oil fever reached southeastern Kansas by the early 1900s. In October 1904, Missouri investors saw an opportunity in a new oil company with wells near proven oilfields at the Kansas-Oklahoma border.

Cahege Oil & Gas Company, headquartered in Carrollton, Missouri, leased 15,000 acres near Caney, Kansas, a region that had produced oil since the early 1890s.

According to the Daily Traveler newspaper in Arkansas City, Kansas, the recently formed company was drilling exploratory wells near Caney – and had “shot two wells on the Broome and St. John leases.” (more…)

By the beginning of the 20th century, Texas wildcatters had fruitlessly pursued oil between Abilene and Fort Worth. They drilled mostly dry holes until 1917 when a gusher brought thousands to the arid region of cattle, cotton and mesquite trees.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Texas wildcatters had fruitlessly pursued oil between Abilene and Fort Worth. They drilled mostly dry holes until 1917 when a gusher brought thousands to the arid region of cattle, cotton and mesquite trees.