by Bruce Wells | Jan 14, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Wildly optimistic promotions during WWI and some drilling, but no gushers.

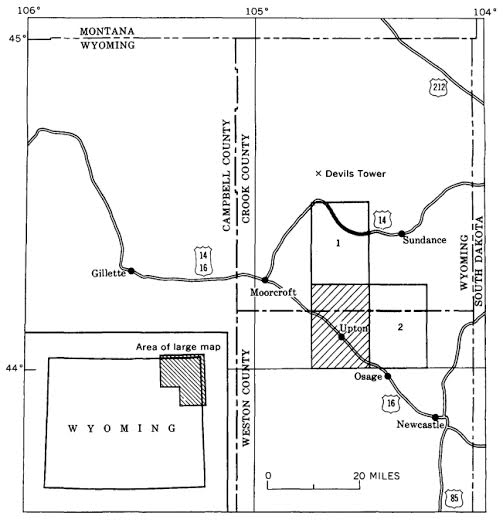

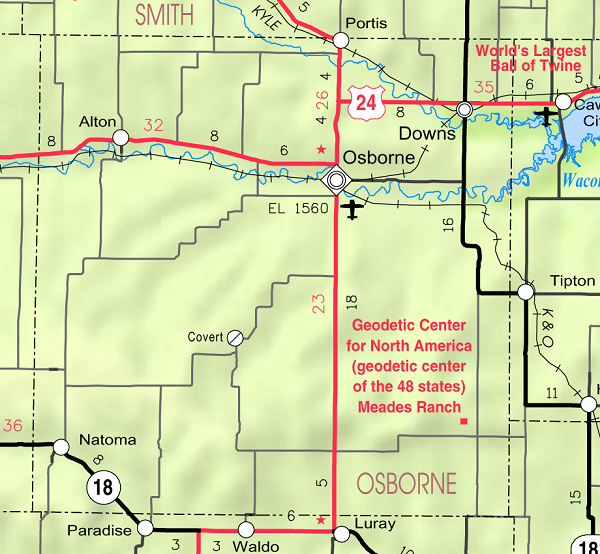

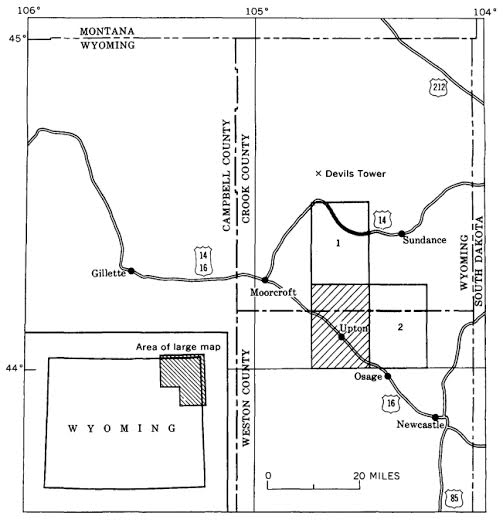

“Oil Excitement at Rocky Ford Field Near Sundance,” proclaimed a front page of the Moorcroft (Wyoming) Democrat on September 14, 1917, describing a “big drill” of the Wyoming-Dakota Company.

“Rocky Ford, the seat of the oil activities in Crook county is about the busiest place around,” the newspaper continued. “Cars come and go, people congregate and the steady churning of the two big rigs continues perpetually.”

Not finished with its excited reporting, the Moorcroft Democrat noted: “Excitement has reached the zenith of tension, and with each gush of the precious fluid, oil stock climbs another notch. The big drill of the Wyoming-Dakota Co. has been pulled from their deep hole until spring. The drill reached 600 feet and was in oil.”

The Rapid City, South Dakota, oil exploration company — reported to have one producing well and three more drilling — was capitalized $500,000 with a nominal par value of 25 cents per share. All the leases were in Crook County and included 3,200 acres in Lime Butte field; 10,000 acres in Rocky Ford field; and 4,000 acres in Poison Creek field.

Since Wyoming would not pass its first “Blue Sky” to prevent fraudulent promotions until 1919, Wyoming-Dakota Oil’s newspaper ads often rivaled patent medicine exaggerations. For example, one ad noted “geologists claim this showing indicates alone 500,000 barrels to the acre.”

Since Wyoming would not pass its first “Blue Sky” to prevent fraudulent promotions until 1919, Wyoming-Dakota Oil’s newspaper ads often rivaled patent medicine exaggerations. For example, one ad noted “geologists claim this showing indicates alone 500,000 barrels to the acre.”

Wyoming-Dakota Oil further enticed investors with, “Your Chance Has Come if you want to make money in Oil.” In Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the Sells Investment Company offered Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company stock reportedly after “a careful selection of conservative issues from among the thousand prospects, offering same to you before higher prices prevail or its present substantial position has been discounted by professional traders. A good clean cut speculation of this character may mean a fortune. Watch this company for sensational developments.”

The United States had entered World War I in April 1917; by November newspapers reported Francis Peabody, chairman of the Coal Committee of the Council of National Defense, was telling the U.S. Senate Public Lands Committee that the country was not producing enough oil to win the war.

“He said if nothing were done to develop new wells the reserve supply would he exhausted in twelve months and production would be 50,000,000 barrels less than requirements,” one newspaper noted. Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company executives took advantage of the opportunity.

“The (war) situation outlined leads us to suggest that you investigate Wyoming-Dakota Oil. ‘We are doing our bit’ by drilling night and day. Ours is an investment worth while. The allotment of Treasury stock at 25 cents is almost sold out and the Directors will advance the price of stock to 50 cents a share (100 per cent on your present investment) on December 15th, 1917.”

The Wyoming-Dakota Oil promotion continued: “By that time our newspaper announcement in the Eastern cities, pointing out the enormous acreage, present production and negotiations for additional valuable holdings will be made known to millions of seasoned investors in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston and Pittsburgh. We feel confident this will result in a demand for this stock that will send the present market price skyward. We trust you will see the wisdom of prompt action before all available stock at 25 cents per share has been purchased by other investors.”

In early 1918, Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company had drilled wells in the Upton-Thornton oilfield and was “holding out high hope of bringing in a gusher in few days.” In July, the Laramie Daily Boomerang reported the company had “two rigs going steadily in Crook County’s Rocky Ford field” — but no oil gushers

Growing investor pessimism was reflected in Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company’s stock prices, which fell in over-the-counter markets from 75 cents bid in June 1919 to 50 cents bid at the end of September. By March 1920, brokers offered 5,000 shares or any part thereof at 5 cents a share.

A final blow to the company was reported in the Laramie Republican of July 25, 1921: “Wyoming-Dakota…has completed pulling the casing from the well which it has been drilling north of town, after having struck a formation said to be granite, at a depth of 715 feet,”

The Laramie newspaper remained optimistic. “While this has a tendency to retard the activities of other interests, it is by no means stopping them entirely and it is to be hoped that another well will be started this summer.”

That did not happen. Reports on Wyoming-Dakota Oil Company disappeared for the next 24 years, until a court summons was published in the January 25, 1945, Sundance (Wyoming) Times. The summons said Wyoming-Dakota Oil — address or place of residence to plaintiff unknown — was being sued in the Sixth District Court of Wyoming.

The world war-inspired oil exploration company has since faded into history, and its stock certificates are valued only by scripophily collectors. For the true story behind a Texas oilfield that played a vital role in the “War to End All Wars,” see Roaring Ranger wins WWI.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Wyoming-Dakota Company” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/wyoming-dakota-oil-company. Last Updated: March 31, 2025. Original Published Date: January 14, 2016.

by Bruce Wells | May 15, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Widely publicized drilling booms attracted investors seeking “black gold” riches — real or imagined.

Exaggerated, questionable, and sometimes fraudulent claims by shady business ventures seeking investors grew in the years following World War I. As the Great Depression approached, many states passed “blue sky laws” to regulate securities sales and protect the public from fraud.

It would take an act of Congress in 1934 to stop skilled business hucksters from taking advantage of unwary investors seeking often fictional profits. Federal lawmakers established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to help rein in exaggerated claims found in newspaper advertisements, mail solicitations, and other stock promotions.

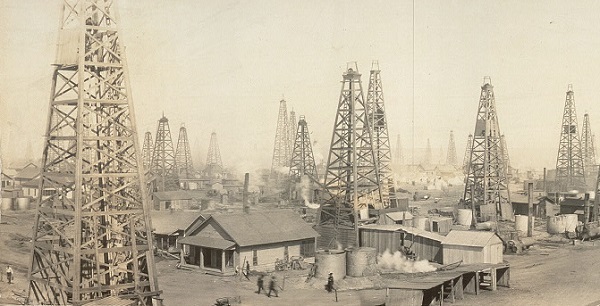

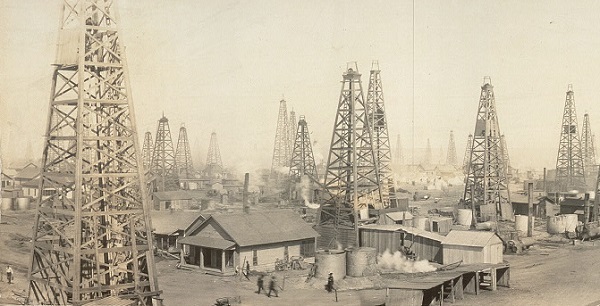

Widely publicized giant oilfield discoveries at Burkburnett, Texas, in 1918 (above) and nearby “Roaring Ranger” one year earlier led to many inexperienced exploration ventures and exaggerated promotions. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Since the U.S. petroleum industry’s earliest booms and busts in Pennsylvania following the Civil War, the need for dependable information and early financial centers — petroleum exchanges — led to a new profession — the oil scout.

As demand for refined kerosene for lamps grew, the search for new oilfields moved to mid-continent. Thousands of exploration and production companies were established. Most drilled dry holes. When wildcat wells (remote) revealed giant oil and natural fields in Texas and Oklahoma, a new generation of business financing hucksters took advantage.

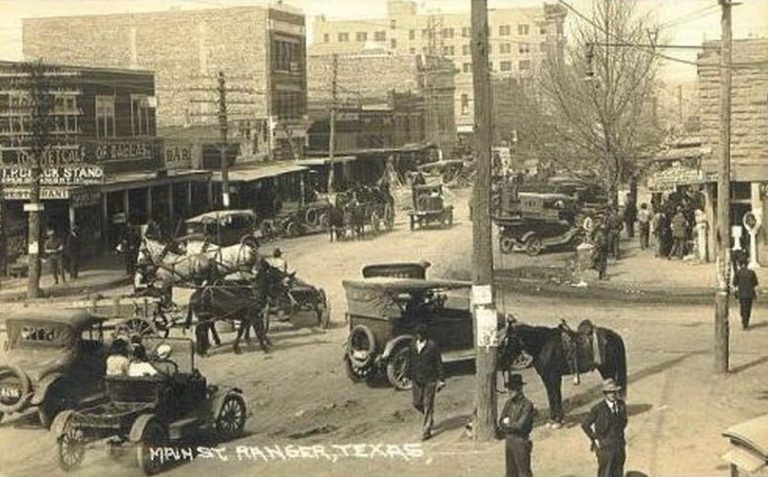

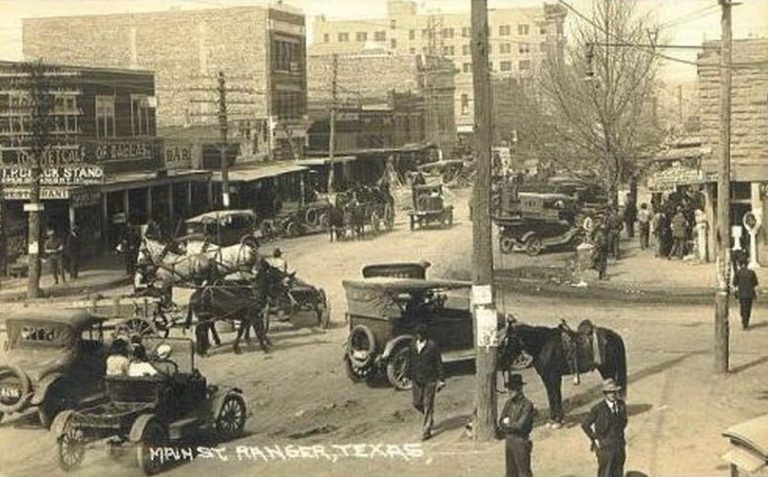

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a massive oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Giant oilfield discoveries in North Texas made headlines, leading to the hundreds of new exploration companies (see Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?). Many began by seeking capital from local investors, often banks, doctors, and civic leaders. Financial swindlers saw opportunities to take advantage of oilfield discoveries and the resulting oil fever.

Newspapers nationwide reported wells with geysers of oil at Electra (1911), Ranger (1917), and the “World’s Wonder Oilfield” of Boom Town Burkburnett (1918). Publicity about these oil booms rekindled enthusiasm for Texas petroleum riches not seen since the giant oilfield discovery at Spindletop Hill in 1901, the famous “Lucas Gusher.”

Sudden, unexpected “black gold” or “Texas tea” wealth brought prosperity to struggling farming communities. Thanks to the Ranger oilfield, Eastland County’s Merriman Baptist Church (and graveyard) was once declared the richest church in America.

Black Gold Dreams

Criminals specializing in financial deception joined the influx of drilling contractors, workers, equipment suppliers, lease brokers, and associated oilfield service companies. In part to combat fraud in North Texas, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), founded in 1917, American Petroleum Institute (API), founded in 1919, and other industry associations organized.

With so many oil boom-inspired companies forming so quickly, the rapid printing of eye-catching but boiler-plate stock certificates often occurred (see Oil Prospects Inc. for one of the most common certificate vignettes).

In a rush to find investors, quickly formed exploration companies ended up using the same oilfield scene for stock certificates. It might have saved time and money by choosing a printer’s common vignette.

Already iconic U.S. boom towns and busts (see the remarkable 1865 rise and fall of Pithole, Pennsylvania) would help launch major companies like Marathon and Texaco, as did the first California oil wells. New petroleum discoveries attracted experienced companies — and many more inexperienced exploration and production ventures that aggressively sought leases, equipment and men, and investors.

However, with little knowledge of the new science of petroleum geology and drilling technologies, few of newly formed companies would find oil. Most did not survive long in the highly competitive oilfields.

Crowding too many wells on leases and a lack of infrastructure for storing and transporting oil harmed the environment. Many companies learned from hard experience, but more went bankrupt without ever finding oil.

Competing exploration companies, lacking petroleum engineers and efficient production technologies, often overproduced geological formations. Unchecked drilling and oversupply in the oil market led prices to collapse as low as 15 cents per 42-gallon oil barrel in the giant East Texas oilfield of the 1930s.

Huckster of Hog Creek

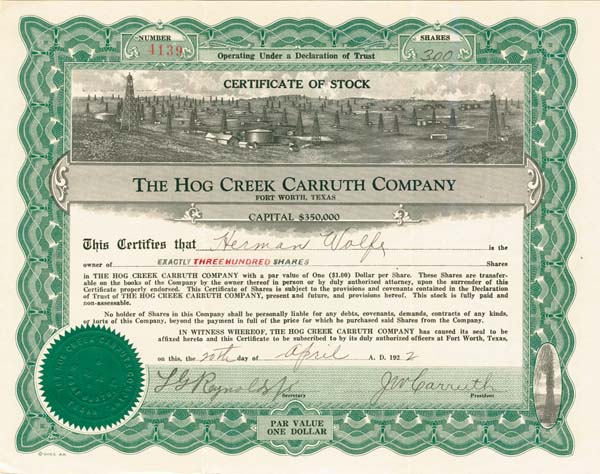

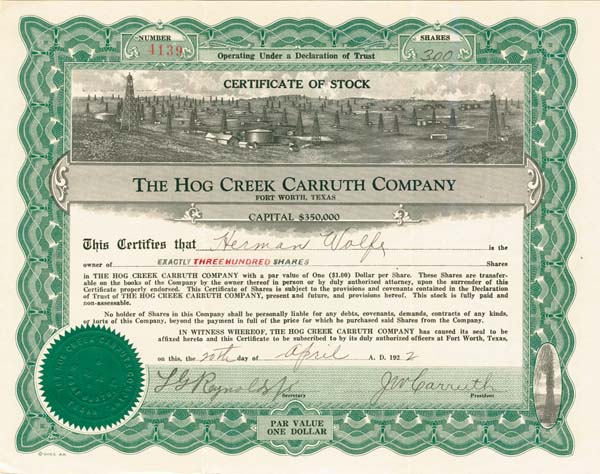

The lure black gold also attracted skilled confidence men who could create oil companies on paper. J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth was among the most notorious.

Financial World in 1912 described “Hog Creek” Carruth as a con man who made a fortune selling worthless oil stocks. The magazine also cited the far better known infamous explorer Dr. Frederick Cook (learn more in Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter).

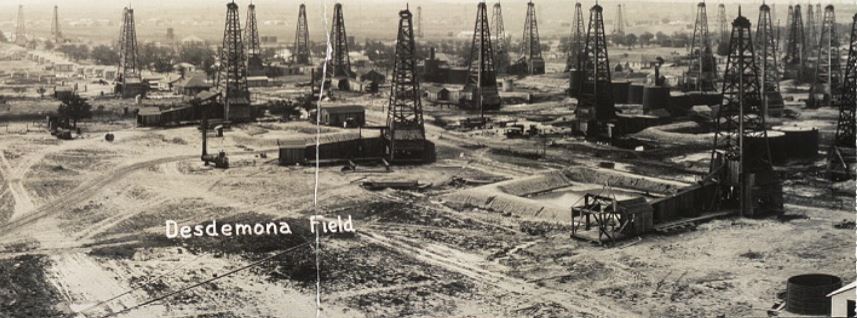

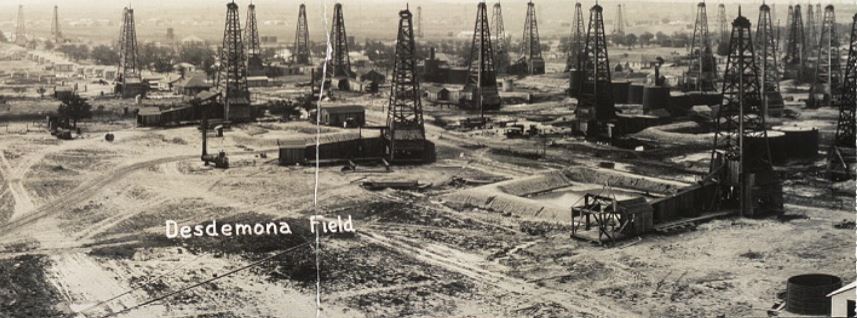

In September 1918 a discovery well near Desdemona blew in after reaching a depth of 2,960 feet, initially producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day. “Unlike Ranger, Desdemona was a small operator’s field. Production reached a peak of 7,375,825 barrels in 1919, and then dropped sharply, chiefly because of over drilling,” according to the Handbook of Texas Online.

“Hog Creek” Carruth proclaimed himself to be the discoverer of the Desdemona oilfield (he was not). He advertised expansively to sell worthless stocks inflated by his phony reputation.

Pilgrim Oil Company

Pilgrim Oil Company formed as a common law trust estate (unincorporated business managed by trustees) in Fort Worth, Texas, on December 20, 1920. The company’s trustees included George M. Richardson and Warren H. Hollister. and was capitalized at $1 million with 100,000 shares offered at par value of $10.

The petroleum company, another fraudulent enterprise of J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth, would be his last.

J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth falsely claimed to have discovered the Desdemona, oilfield, along Hogg Creek. Detail from circa 1919 panoramic photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The oilfield along Hog Creek had been discovered in 1918, just one year after the famous Ranger well. This new field at Desdemona (once called Hog Town) attracted the usual rush of new exploration companies, many with little or no drilling experience.

Among the Eastland County startups, a wily financial conman’s Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company profited by colorful stock sale advertisements to attract investors.

The skillfully exaggerated promotions of Carruth prompted one contemporary writer to admire the crook’s audacity. “Any reader who cannot get a thrill out of Carruth’s highly colored advertising literature is indeed phlegmatic,” the observer declared.

But harm to many small, unwary investors was real. Most of the stock sales’ dollars went into Carruth’s pockets instead of his companies. Even the failure of his oil companies became part of his schemes.

Hogg Oil + Hog Creek Carruth Oil

Carruth merged two of his insolvent petroleum companies — Hogg Oil Company and Hogg Creek Carruth Oil Company — to create the Pilgrim Oil Company. His latest venture attracted some skeptical attention from financial magazine editors. The Pilgrim Oil Company, “makes a business of gathering in defunct oil companies,” reported Financial World.

As part of his connived merger game plan, stockholders of the two bankrupt Carruth oil ventures had to buy an additional 25 percent of Pilgrim Oil Company shares (in cash) or lose their investments entirely. Carruth used this money to pay dividends, thereby luring more buyers into his petroleum company Ponzi scheme.

Financial World noted, “This is a promoter’s way of reloading old stockholders with additional $25 worth of stock for every $100 they hold in a defunct company.”

J.W. Carruth merged his fraudulent Hogg Creek Carruth Oil with his other fraudulent oil company to create Pilgrim Oil company, a Ponzi scheme using investors’ purchase money to pay dividends and lure more buyers.

In 1923, a federal court indicted J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth for mail fraud. Also indicted were Pilgrim Oil Company trustees Richardson and Hollister. Eighty-nine other shady characters also were named in a sweeping indictment aimed at stock hucksters.

U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth

Federal prosecutors reviewed financial harm to innocent Pilgrim Oil Company shareholders, who pleaded to the court for justice.

“False, fraudulent, and untrue representations were made for the purpose of inducing plaintiffs to buy the said stock of the said two companies, and for the purpose of cheating, swindling, and defrauding plaintiffs out of their money, and did cheat, swindle, and defraud plaintiffs out of their said money,” the attorneys declared.

“That in 1922, and for a long time prior and subsequent thereto, defendant was engaged in handling and selling oil stock certificates and owned and controlled interests in various oil companies and concerns in this state,” the prosecutors added. Dozens of convictions followed.

Carruth earned a one-year sentence in Leavenworth, Kansas. He joined the federal penitentiary’s oil-scheme alumni Dr. Frederick Cook, the fraudulent Arctic explorer turned oil well promoter. Pilgrim Oil Company and the other Carruth company shareholders were left with stock certificates of no value, except perhaps as a family stories and heirlooms.

Convicted felon “Hog Creek” Carruth, who died in obscurity in 1932, should not be confused with former Texas Governor James S. “Big Jim” Hogg, who helped discover the important West Columbia oilfield in 1917 — learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells.

New Jersey Oilfield?

A West Coast newspaper in 1916 reported on a rare attempt to find an East Coast oilfield. “Lewis Steelman, the man who has been prospecting for oil near Millville, N.J., for some time, has begun active work to locate an oil well and he confidently expects to strike the fluid,” reported California’s Santa Ana Register.

In New Jersey, the recently established Steelman Realty Gas & Oil Company was selling stock buttressed by the declarations of Dr. H. J. von Hagen, who company executives cited as “one of the world’s greatest living geologists and petroleum engineers.” Learn more in Fake New Jersey Oil Well.

More articles about U.S. exploration and production companies and links for further research can be found in Oil Stock Certificates.

_______________________

Recommended Reading (October 9): The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS annual supporter. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pilgrim-oil-company-exploiting-oil-fever. Last Updated: May 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 9, 2021.

.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

Elk Basin United Oil Company incorporated in 1917 seeking oil riches in Wyoming’s booming Elk Basin oilfield. Oilfields found in North Texas, including a 1911 gusher at Electra, already had resulted in a rush of new exploration ventures – and created boom towns like Burkburnett.

Wherever found, America’s newly discovered oilfields led to the founding of many exploration ventures that competed against more established companies.

Newly formed companies frequently struggled to survive as competition for financing, leases, and drilling equipment intensified, especially as exploration moved westward.

Wyoming Oilfields

In a remote, scenic valley on the border of Wyoming and Montana, a discovery well opened Wyoming’s Elk Basin oilfield on October 8, 1915. Wyoming’s earliest oil wells had produced quality, easily refined oil as early as 1890.

Drilled by the Midwest Refining Company, the wildcat well produced up to 150 barrels of oil a day of a high-grade, “light oil.” Credit for oil discovery is given to geologist George Ketchum, who first recognized the Elk Basin as a likely source of oil.

“Gusher coming in, south rim of the Elk Basin Field, 1917.” Photo courtesy American Heritage Center.Ketchum, a farmer from Cowly, Wyoming, in 1906 had explored the area with C.A. Fisher, who had been the first geologist to map a region within the Bighorn Basin southeast of Cody, Wyoming, where oil seeps were discovered in 1883.

The Elk Basin, which extends from Carbon County, Montana, into northeastern Park County, Wyoming, attracted further exploration after the 1915 well. More successful wells followed.

Once again, petroleum discoveries in unproved territory attracted speculators, investors, and new companies – including the Elk Basin United Oil Company.

Established petroleum companies like Midwest Refining — and the Ohio Oil Company, which would become Marathon Oil — came to the Elk Basin. These oil companies had the financial resources to survive a run of dry holes or other exploration hazards.

The exploration industry’s many smaller and under-capitalized companies would prove especially vulnerable.

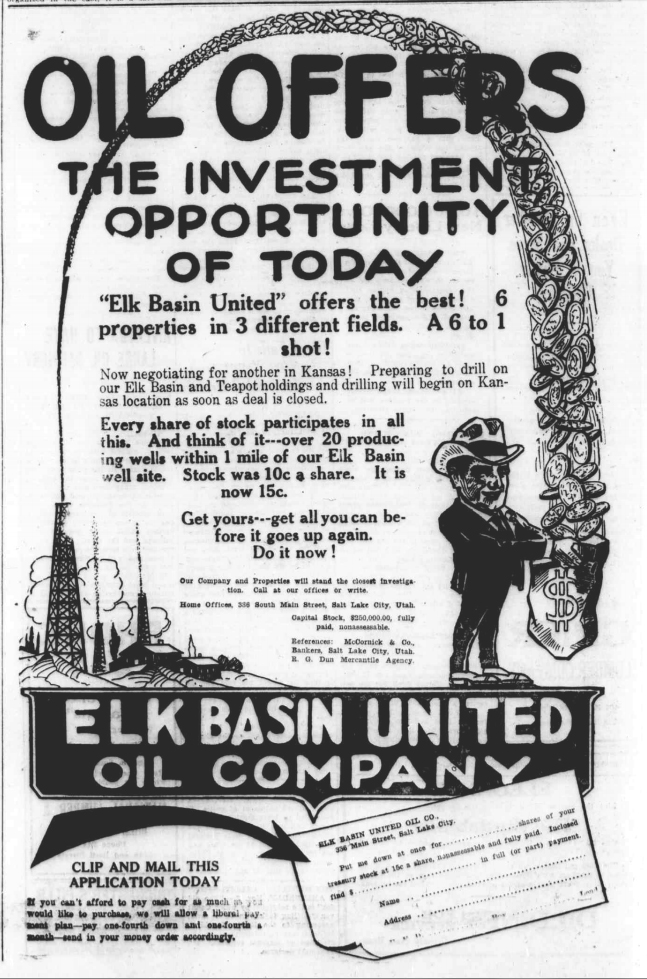

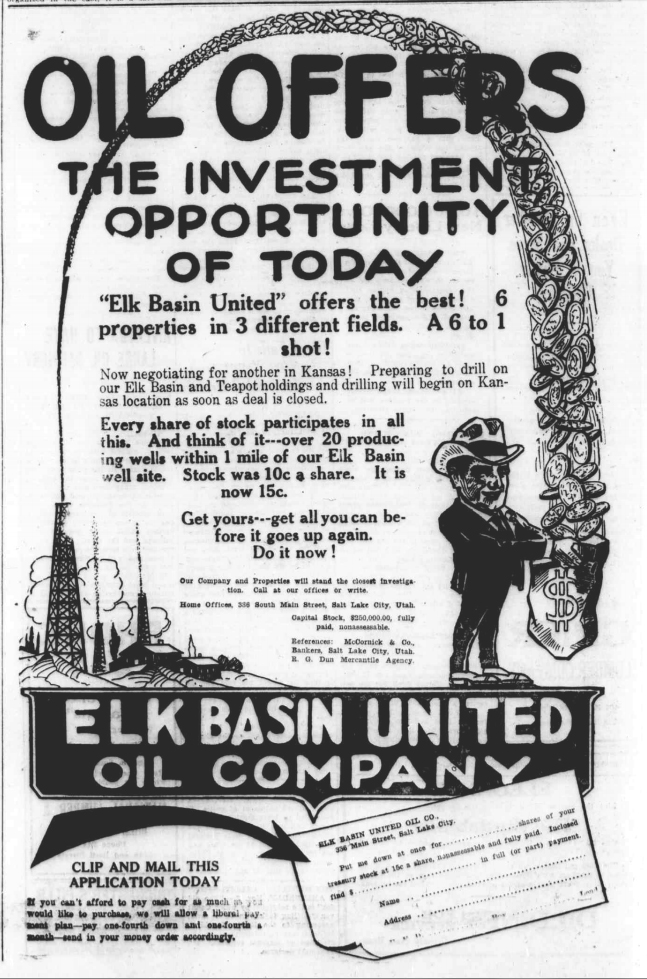

Audacious advertising claims helped Elk Basin United Oil Company compete for investors.

Is My Old Oil Stock Worth Anything features several such small players in Wyoming’s petroleum history, including the notorious Dr. Frederick Albert Cook (Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter). Even Wyoming’s famous showman, Col. William F. Cody, got caught up in the state’s oil fever (Buffalo Bill Shoshone Oil Company).

Elk Basin United Oil Company

Elk Basin United Oil Company of Salt Lake City, Utah, incorporated on July 30, 1917, and acquired a lease of 120 acres in Wyoming’s Elk Basin oilfield. By February 1918, company stock sold for 12 cents a share.

Enthusiastic newspaper ads promoted its “6 properties in 3 different fields…A 6 to 1 shot!” Twenty producing wells were reputed to be within one mile of Elk Basin United Oil’s Wyoming well site.

Meanwhile, Elk Basin United Oil reported expansion plans underway in a growing Kansas Mid-Continent oilfield. The company secured leases near Garnett and completed four producing oil wells, yielding a total of about 500 barrels of oil a month. It added an additional 112 acres and planned a fifth well.

Prairie Pipe Line Company (later Sinclair Consolidated) completed pipelines into the Garnett field through which several companies looked to transport their oil production.

However, growing competition from better funded exploration ventures and low crude oil prices ranging between $1.10 and $1.98 per barrel of oil in 1917 and 1918 drove many small companies into consolidations, mergers or bankruptcy.

Elk Basin United Oil, exploring back in Wyoming by March 1919, sought a lease on the property of the First Ward Pasture Company bordering the Utah line, “with a view of prospecting the property declare the surface showing to be very favorable for an oil deposit.” But financial issues continued to burden the company.

In December 1919, Oil Distribution News reported Basin United Oil Company was negotiating mergers with the Anderson Oil Company and the Kansas-United Oil Company, with a proposed capitalization of $1 million. With no results of the planned combination documented, Elk Basin United Oil Company disappeared from financial records soon thereafter.

_______________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Elk Basin United Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/elk-basin-united-oil-company. Last Updated: September 29, 2022. Original Published Date: October 1, 2021.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Boom and bust of an obscure mid-continent petroleum company began in 1917.

The International Petroleum Register noted formation of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company as a Delaware corporation in 1917. With capitalization of $5 million in common stock authorized and more than $734,000 issued, the company obtained leases in Muskogee, Tulsa, Rogers, and Okmulgee counties in Oklahoma, and in Allen County, Kansas.

Major north Texas oilfield discoveries in Electra (1911) and Ranger (1917) attracted petroleum companies to the mid-continent. As oil demand soared during World War I, hundreds of new exploration and productions companies formed — and sought investors. Most of these companies would not survive.

By 1919, Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining’s lease ownership had expanded to 10,313 acres with an additional 815 acres from its acquisition of Tulsa Union Oil Company. About this time, all of the company’s petroleum production was sold to Prairie Oil and Gas Company.

Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining meanwhile continued drilling for oil in Coffee County, Kansas, and elsewhere, and the company’s estimated production reached 10,000 barrels of oil each month — a promising development for investors. The financial magazine United States Investor added a positive endorsement in May 1920 after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining reported production of 27,000 barrels of oil worth $65,000.

“It appears that this company is further along the road to development that a great many of the new oil companies, though whether its shares at the present offering price of $2.50 on the basis of a $1 par represent an extravagant price, cannot be told until further developments have occurred,” United States Investor reported.

However, six months later, the company’s shares were selling for less than 14 cents. Records of what went wrong are obscure. There are references to a convoluted business venture with another oil company. The deal was orchestrated by New York financier Mrs. Ada M. Barr after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining had failed in January 1921.The next month, after being put in the hands of a receiver, the company’s assets were sold for $87,400.

The buyer was Mrs. Barr, who soon would be enveloped in controversy and litigation of her own.

Acorn Petroleum Corporation, represented by Mrs. Barr, offered bonds in the amount of $150,000 of Acorn Petroleum Corporation on the basis of $250 in bonds for each $1,000 of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining stock held.

“The new company is operating the properties and has twenty-three producing wells, giving about ninety barrels of oil a day. The present low price for oil does not enable the company to earn sufficient income to pay interest on its bonds,” United States Investor noted. “Mrs. A.M. Barr, who arranged the financing of the new company, says that as soon as oil advances to a price that will permit, accrued interest on the bonds and dividends on the stock will be paid.”

But they weren’t.

By March 1923, investor Lewis H. Corbit filed a petition on behalf of a large number of local purchasers of stocks in the Acorn Petroleum Corporation of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The petition in the United States District court sought to determine the value of the local holdings, which represent an investment of approximately $100,000.

According to records, “In his complaint, asking for an investigation, Corbit alleges a stock, fraud in which $ 500,000 is involved. Certificates of shares held here were sold by a Mrs. A. M. Barr, it is disclosed in the petition.”

Further financial records and other details about Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company, Acorn Petroleum Corporation, and Mrs. Ada M. Barr can be research through the Library of Congress’ online Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

___________________

The stories of exploration and production (E&P) companies joining U.S. petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 6, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

Oil from the giant El Dorado oilfield was often featured in petroleum industry news as America prepared to enter World War I in April 1917. The mid-continent field, discovered two years earlier east of Wichita, had made headlines and launched a Kansas oil boom.

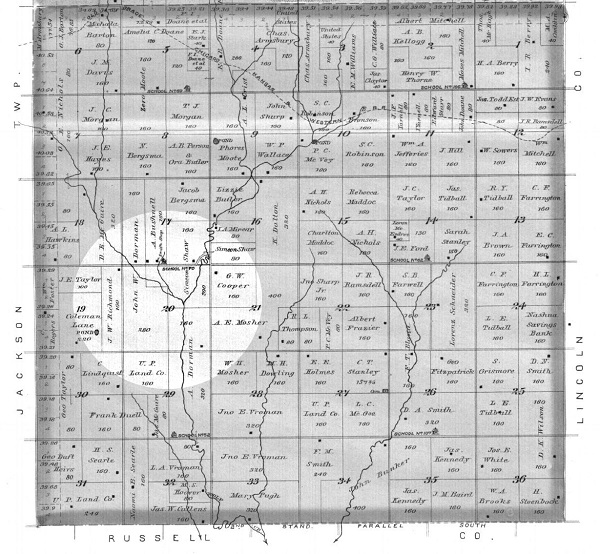

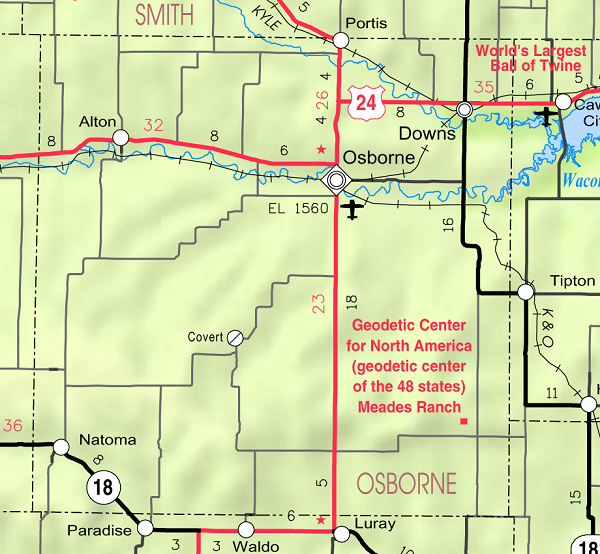

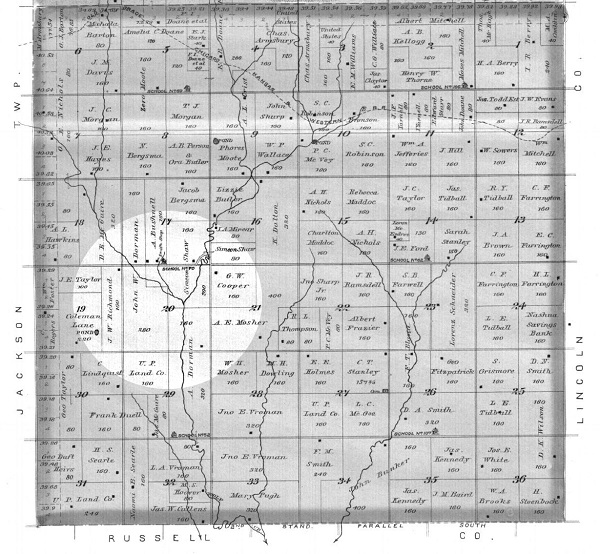

More than 200 miles to the northwest, the Delhi Oil Company would soon bet its fortunes on a wildcat oil well in Osborne County – and lose. In a chronology not unlike many small, community-based oil speculations, Delhi Oil began by seeking investors to fund its exploratory drilling.

The venture was started by Isaac M. Mahin, a state senator, and F.W. Mahin, both lawyers who owned the North Kansas Land & Loan Company in Smith Center. In November 1917, the Topeka Daily Capital reported the two men and other businessmen had “proposed to enter the oil hunting industry” by incorporating the Delhi Oil Company “with a capital stock of $60,000, all of which will be expended in drilling.”

Delhi Oil secured leases in Smith and Osborne counties and by March 1918 had contracted for an 84-foot drilling rig. The company advertised in earnest for potential investors. “This is good news for the people of this county as it marks the beginning of actual oil development in Osborne County,” proclaimed one editorial ad in the Salina Evening Journal.

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.”

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.”

Although the first Delhi Oil well had yet to be spudded by early 1919, efforts to secure funds and investors continued. “Salina stands to benefit greatly by the development of the field,” stated one promotion. “Should gas be found, Salina’s fuel bill would be cut in half. Should a good oil field develop, Salina will become a refining and distributing center. And further, you have the assurance that every dollar you invest in this venture will be used in development, and also that your interest applies to the entire 5,320 acres.”

The newspaper’s praise continued: “This is to certify that we have thoroughly investigated the organization and plans of the Delhi Oil Company, are interested in their success and believe their stock to be a good, clean investment, one well worth your careful consideration.”

Sufficient working capital was finally secured and by May 1919, Delhi Oil’s wildcat rig was erected in Osborne County on the Dorman lease (Section 20 of Township 10 South, Range 11 West). It took eight months of drilling for the Dorman No. 1 well to reach 1,510 feet, ostensibly having seen a “show of oil” at just 500. Enthusiastic testimonials appeared in January 1921 newspapers:

“This news, together with the rumors that the company nine miles east of the Delhi lease is building oil tanks, has caused no little excitement among the people who are interested in the projects. There are real indications that a big field is about to be opened and the men who have their money invested are beginning to take heart over the outlook.”

“At this time they are drilling at a little more than 2,000 feet, in limestone,” reported the Western Kansas World in WaKeeney. “Delhi oil prospects are getting brighter and brighter each day. Sunday a large number of stock holders and others interested in the well were out watching the drill go down.”

Echoing a popular theme, the newspaper said the well “may mean untold wealth to Osborne County,” and on June 30, 1921, noted “the Delhi Oil Co. well near Luray is down 2,800 feet and it is said you can smell gas when you get near it.” But within four months, drilling at the Dorman No. 1 well was shut down at 2,930 feet. Securing working capital from investors remained a problem.

On April 13, 1922, the Salina Evening Journal reported Delhi Oil was “organizing in every town and township in Osborne county in an attempt to raise the necessary funds to complete the well on their leases. It is estimated that $20,000 will be needed to complete the project and one-half of that amount has already been raised, so that the big drive will have for its object the raising of the final $10,000.”

The newspaper added that “the money must be raised in the next two weeks, and if it is not forthcoming the well will be abandoned, as the company can no longer finance the drilling, although within 300 feet of what is believed to be a paying pool of oil.” Four days later the paper announced, “The Delhi Oil Company is making a county-wide drive in an endeavor to raise funds to complete their project within the next ten days.”

Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. At either depth, the hole was dry and shareholders lost their investment. Kansas Corporate Commission records show that Delhi Oil forfeited its charter to do business for failure to file required annual reports.

Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. At either depth, the hole was dry and shareholders lost their investment. Kansas Corporate Commission records show that Delhi Oil forfeited its charter to do business for failure to file required annual reports.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Since Wyoming would not pass its first “Blue Sky” to prevent fraudulent promotions until 1919, Wyoming-Dakota Oil’s newspaper ads often rivaled patent medicine exaggerations. For example, one ad noted “geologists claim this showing indicates alone 500,000 barrels to the acre.”

Since Wyoming would not pass its first “Blue Sky” to prevent fraudulent promotions until 1919, Wyoming-Dakota Oil’s newspaper ads often rivaled patent medicine exaggerations. For example, one ad noted “geologists claim this showing indicates alone 500,000 barrels to the acre.”

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.”

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.” Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the

Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the