Protected: Oil & Gas History News, March 2023

Password Protected

To view this protected post, enter the password below:

To view this protected post, enter the password below:

Elk Basin United Oil Company incorporated in 1917 seeking oil riches in Wyoming’s booming Elk Basin oilfield. Oilfields found in North Texas, including a 1911 gusher at Electra, already had resulted in a rush of new exploration ventures – and created boom towns like Burkburnett.

Wherever found, America’s newly discovered oilfields led to the founding of many exploration ventures that competed against more established companies.

Newly formed companies frequently struggled to survive as competition for financing, leases, and drilling equipment intensified, especially as exploration moved westward.

In a remote, scenic valley on the border of Wyoming and Montana, a discovery well opened Wyoming’s Elk Basin oilfield on October 8, 1915. Wyoming’s earliest oil wells had produced quality, easily refined oil as early as 1890.

Drilled by the Midwest Refining Company, the wildcat well produced up to 150 barrels of oil a day of a high-grade, “light oil.” Credit for oil discovery is given to geologist George Ketchum, who first recognized the Elk Basin as a likely source of oil.

“Gusher coming in, south rim of the Elk Basin Field, 1917.” Photo courtesy American Heritage Center.Ketchum, a farmer from Cowly, Wyoming, in 1906 had explored the area with C.A. Fisher, who had been the first geologist to map a region within the Bighorn Basin southeast of Cody, Wyoming, where oil seeps were discovered in 1883.

The Elk Basin, which extends from Carbon County, Montana, into northeastern Park County, Wyoming, attracted further exploration after the 1915 well. More successful wells followed.

Once again, petroleum discoveries in unproved territory attracted speculators, investors, and new companies – including the Elk Basin United Oil Company.

Established petroleum companies like Midwest Refining — and the Ohio Oil Company, which would become Marathon Oil — came to the Elk Basin. These oil companies had the financial resources to survive a run of dry holes or other exploration hazards.

The exploration industry’s many smaller and under-capitalized companies would prove especially vulnerable.

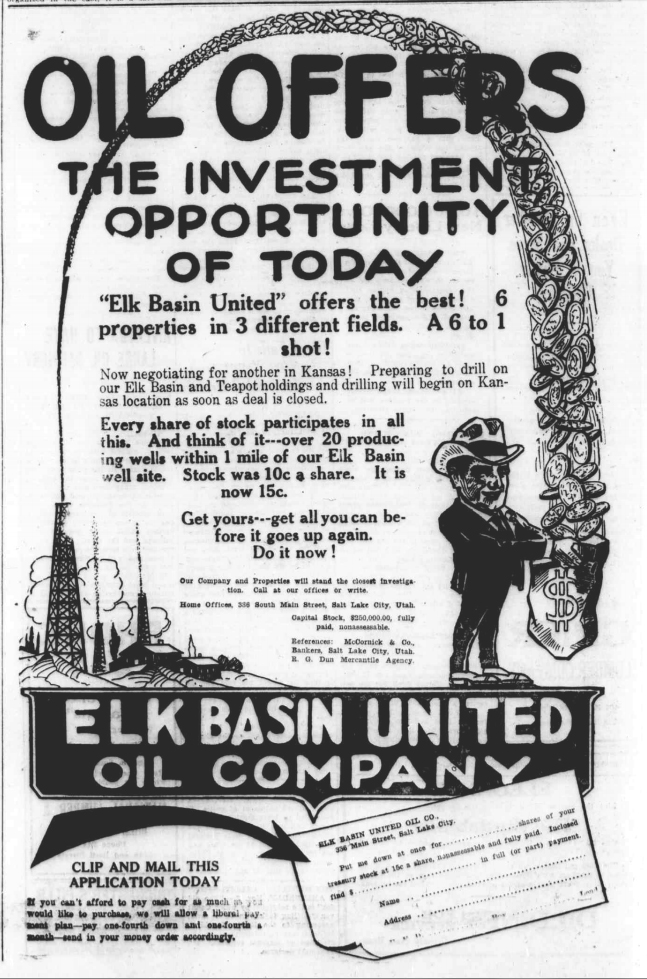

Audacious advertising claims helped Elk Basin United Oil Company compete for investors.

Is My Old Oil Stock Worth Anything features several such small players in Wyoming’s petroleum history, including the notorious Dr. Frederick Albert Cook (Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter). Even Wyoming’s famous showman, Col. William F. Cody, got caught up in the state’s oil fever (Buffalo Bill Shoshone Oil Company).

Elk Basin United Oil Company of Salt Lake City, Utah, incorporated on July 30, 1917, and acquired a lease of 120 acres in Wyoming’s Elk Basin oilfield. By February 1918, company stock sold for 12 cents a share.

Enthusiastic newspaper ads promoted its “6 properties in 3 different fields…A 6 to 1 shot!” Twenty producing wells were reputed to be within one mile of Elk Basin United Oil’s Wyoming well site.

Meanwhile, Elk Basin United Oil reported expansion plans underway in a growing Kansas Mid-Continent oilfield. The company secured leases near Garnett and completed four producing oil wells, yielding a total of about 500 barrels of oil a month. It added an additional 112 acres and planned a fifth well.

Prairie Pipe Line Company (later Sinclair Consolidated) completed pipelines into the Garnett field through which several companies looked to transport their oil production.

However, growing competition from better funded exploration ventures and low crude oil prices ranging between $1.10 and $1.98 per barrel of oil in 1917 and 1918 drove many small companies into consolidations, mergers or bankruptcy.

Elk Basin United Oil, exploring back in Wyoming by March 1919, sought a lease on the property of the First Ward Pasture Company bordering the Utah line, “with a view of prospecting the property declare the surface showing to be very favorable for an oil deposit.” But financial issues continued to burden the company.

In December 1919, Oil Distribution News reported Basin United Oil Company was negotiating mergers with the Anderson Oil Company and the Kansas-United Oil Company, with a proposed capitalization of $1 million. With no results of the planned combination documented, Elk Basin United Oil Company disappeared from financial records soon thereafter.

_______________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Elk Basin United Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/elk-basin-united-oil-company. Last Updated: September 29, 2022. Original Published Date: October 1, 2021.

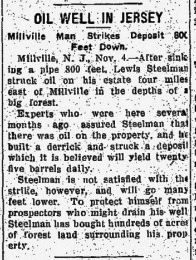

There would be no East Coast oil boom, despite enthusiastic promotions of a mythical New Jersey oilfield after a family in Millville decided to expand from real estate into oil exploration business on their farm in Cumberland County.

As early as August 1916, a West Coast newspaper covered the unusual attempt to find oil East Coast oil. “Lewis Steelman, the man who has been prospecting for oil near Millville, N.J., for some time, has begun active work to locate an oil well and he confidently expects to strike the fluid,” reported California’s Santa Ana Register.

“Steelman has secured options on the property in the vicinity of his estate at Cumberland, near here, and has erected a derrick 75 feet high, by which the drilling will be done,” the newspaper explained.

A New Jersey “oil well” drilled in 1916 was said to have found a previously unknown geologic oil-bearing formation.

Steelman Realty Gas & Oil Company officially incorporated on November 13, 1916, with $300,000 in capital. Most of the company’s stock was sold to Pittsburgh independent producers. Officers included Lewis Steelman, Merton Steelman and Leroy Steelman. Their objective was to “drill for natural gas and oil on lands of the company.”

When a Steelman exploratory well reportedly discovered oil 800 feet deep on a 1,500-acre tract, the Petroleum Gazette in Titusville, Pennsylvania, took note of the discovery.

“Lewis Steelman struck oil on his estate four miles east of Millville in the depths of a big forest,” the Gazette reported. “Experts who were here several months ago assured Steelman that there was oil on the property and he built a derrick and today struck a deposit which it is believed will yield 25 barrels of crude oil daily.”

The Petroleum Gazette (published where the first U.S. oil well had been drilled in 1859) added that Steelman was not satisfied with the oil strike and would “go a few feet lower to protect himself from prospectors who might drain his well.”

With Steelman Realty Gas & Oil said to be buying hundreds of acres of forest land surrounding Steelman property, company stock sales were buttressed by the declarations of geologist Dr. H. J. von Hagen, cited as “one of the world’s greatest living geologists and petroleum engineers.”

Dr. von Hagen also predicted this previously unknown geologic oil-bearing formation extended into Maryland and West Virginia, varied in width, “but is nowhere more than fifteen miles across.” Dr. von Hagen had spent two years in tracing it, the newspaper added.

Covering news of the New Jersey wildcat well from North Carolina, the Durham Morning Herald reported Dr. von Hagen as one of the men who had struck oil at Millville. The newspaper quoted the geologist as saying the petroleum came from “a great belt which starts near Moncton, New Brunswick, reappears at the eastern end of Long Island, runs near Lakewood, N.J.”

Newspapers as far away as California reported the dubious New Jersey oil discovery.

“Dr. von Hagen says he and his associates have received a $100,000 offer for the well which they are sinking, and from which they can get about fifteen barrels of oil a day, though the final depth has not been reached,” reported the Morning Herald. Dr. Von Hagan himself leased thousands of acres of land east of Millville, as well as nearby Hammonton.

It looked like the beginning of New Jersey’s first commercial oil production. Then Bridgewater’s Courier-News reported startling news. “Dr. von Hagen and His Bag Gone,” the account began. “Residents of this city, Millville and other places in this section are puzzled over Dr. von Hagen and his oil locating scheme. The doctor is away, his offices here are unoccupied at the present, no oil has been struck, and no one has been asked to buy stock.”

The Courier-News also had something to say about the geologist and his unusual methods. “The story about the doctor sinking his wells for wireless communication with Germany is all rot. He claims to have discovered the secret of locating oil under ground. He has a little bag with a golden cord attached. When that Is held over ground where there is oil the bag becomes agitated and swings violently.”

Meanwhile, another account of the well from the Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter said the discovery had “brought considerable notoriety to a locality in which geologic conditions, as promptly announced by the State geologist, are unfavorable to the occurrence of oil in commercial quantities…No instance of oil seepage and no oil-bearing shales have ever been observed by any worker on the State Geological Survey.”

The publication added that the survey had been “continuously active since 1864” and the geology of New Jersey had been studied “to a more minute degree than that of any other State, the conclusion seems irresistible that they (oil-bearing formations) do not occur.”

Articles describing a successful oil well in New Jersey nonetheless excited investors and apparently attracted more drillers and cable-tool rigs. “Discovery of Flow Near Millville, N.J., Starts Rush of Prospectors,” proclaimed the Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times. “The Steelman Realty, Gas and Oil Company, which recently struck oil at their well on the 1,500 [acre] tract three miles east of Millville, has received pipe for a second well which will be started at once.”

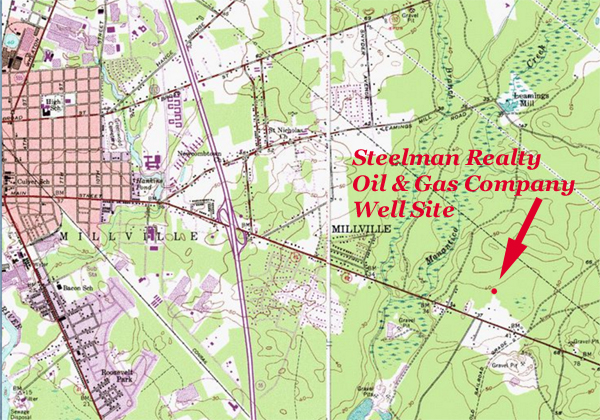

“The old timers called the woods road leading to the site Oil Well Road,” notes one Millville resident.

The newspaper said pipe and drills had arrived “for three independent concerns, and prospectors from Oklahoma and elsewhere will sink the wells on leased ground near the location of the well where oil has been struck.”

However, the state geologist remained dubious. “All drilling for oil here is extremely speculative and should be undertaken only by those who fully understand the hazards of the game and can afford to lose their entire venture,” he warned. “The public should therefore beware of stock-selling schemes based on reported discoveries or assumed occurrences of oil in New Jersey.”

An October 1917 report on the well’s status noted technical problems. “For months no work was done at the well owing to the loss of tools and obstruction of the casing (see Fishing in Petroleum Wells).” Despite this trouble, “the sale of stock in an oil and realty company controlling adjoining territory was actively pushed by some of the persons interested in the company which sank the well.”

Millville resident George Martin tracked down the abandoned New Jersey well.

Perhaps the New Jersey State Geologist had the last word about the well when:

“Facts have come to his knowledge which verify what he formerly suspected, namely, that the reputed discovery at Millville was a fake pure and simple, although not all of the persons interested in drilling the well had knowledge of the fraud.”

Steelman Realty, Gas and Oil Company stock certificates today are valued by collectors as remnants of a failed petroleum speculation scheme. “New Jersey Not a Good Field for Oil Investments,” concluded the April 1921 Oil Trade Journal.

For a thoroughly researched chronology of the Steelman well, visit the Millville Historical Society and see Paul M. McConnell’s “A Century Ago, Southern New Jersey Had Its Fifteen Minutes of Fame.”

Home to major East Coast refineries, New Jersey has never produced commercial quantities of oil or natural gas.

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society thanks long-time Millville resident George R. Martin, who trekked the countryside to find the Steelman well in 2017. “”My father and my uncle took me to see it many years ago,” he recalled. “The old timers called the woods road leading to the site Oil Well Road.”

The stories of exploration and production companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Fake New Jersey Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/steelman-realty-gas-oil-company. Last Updated: August 24, 2022. Original Published Date: July 20, 2018.

Colorado oil history revealed from researching an old oil company stock certificate.

Dated March 1902, a stock certificate had been issued by a Wyoming venture — the Savannah Oil, Coal and Gas Company. The company president’s signature was too hard to make out, according to the guest post on the the American Oil and Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) Stock Certificate Q & A Forum — a popular section of Is My Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The poster added: “I would appreciate any information available on this company. Researching for my 90-year-old Mom!” Like many others, the visitor to AOGHS website sought information about his family’s stock certificate.

Drilling for natural gas in 2005 in the Denver Basin’s Wattenberg gas field, discovered in 1970. Photo courtesy geologist and engineer Dan Plazak.

The story of Savannah Oil, Coal and Gas began just before its incorporation — when a headline-making oilfield discovery at Boulder, Colorado, inspired the founding of many exploration companies. Most of these ventures would not survive.

According to a 1902 biennial report from the Colorado Secretary of State, Savannah Oil, Coal and Gas Company had a principal office in Cheyenne, Wyoming, for doing business in Colorado. The also report listed a T.F. Little as a sales agent with Boulder as a place of business.

Natural oil seeps first drew “bobbers” to the Boulder area, according to a 1905 Colorado Geological Survey report.

“The principle on which the use of a bobber rests is the same as that by which the proper site of a water well is determined by the involuntary turning of a witch-hazel sprout when held in the hand,” the survey noted.

In the Boulder field, bobbers fixed “the exact location off a large proportion of the wells, the geological survey added. One such oil well was on the McKenzie farm, about three miles northeast of town. It was the discovery well that opened the Boulder oilfield — the first of many in the Denver Basin.

The McKenzie well that launched drilling in Boulder field would pump oil until 2007.

Initially producing 70 barrels of oil a day, the 1901 McKenzie well spawned a scramble for nearby mineral leases as the local newspaper, The Daily Camera, reported a thousand companies formed in three months. Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company was among them.

Despite the disdain of petroleum geologists, modern bobbers and other dowsing tools are available from the American Society of Dowsers (ASD), established in 1961. For attempts of finding Texas oilfields using psychic readings, see Luling Oil Museum and Crudoleum.

Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas incorporated on February 11, 1902, with C.B. Younglove as president and its principal agent in Boulder. The vice president was T.F. Little.

Capitalized at only $15,000 with its main office in Cheyenne, Wyoming, the company needed early success in the Boulder oilfield to survive. When Younglove learned the Otero Company had drilled and completed producing oil wells northeast of Boulder, he managed to secure leases close by.

Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company would drill in Boulder County’s Section 8 and Section 9, Township 1 North, Range 70 West (Public Land Survey System – PLLS). Today, the well sites are near the intersection of Valhalla Drive and Kelso Road.

By late 1902, a business journal reported Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas drilling for oil in the Boulder field.

“T.F. Little, the vice president says they have one well 2,600 feet deep with about 1,000 feet of oil in it, and have recently moved derrick to land adjoining the Otero well (which is now producing about 100 barrels per day), and the run hole is now about 300 feet deep, just over the fence from the Otero property,” noted the American Investor, adding Vice President Little, “also says they are not now offering any stock for sale.”

By 1905, the U. S. Geological Survey (Bulletin No. 265) published more detail on the Younglove and Savannah producing oil wells, depths, unsuccessful attempts or “dry holes,” and use of nitroglycerin for fracturing oil-producing geologic formations (learn more in Shooters – A Fracking History).

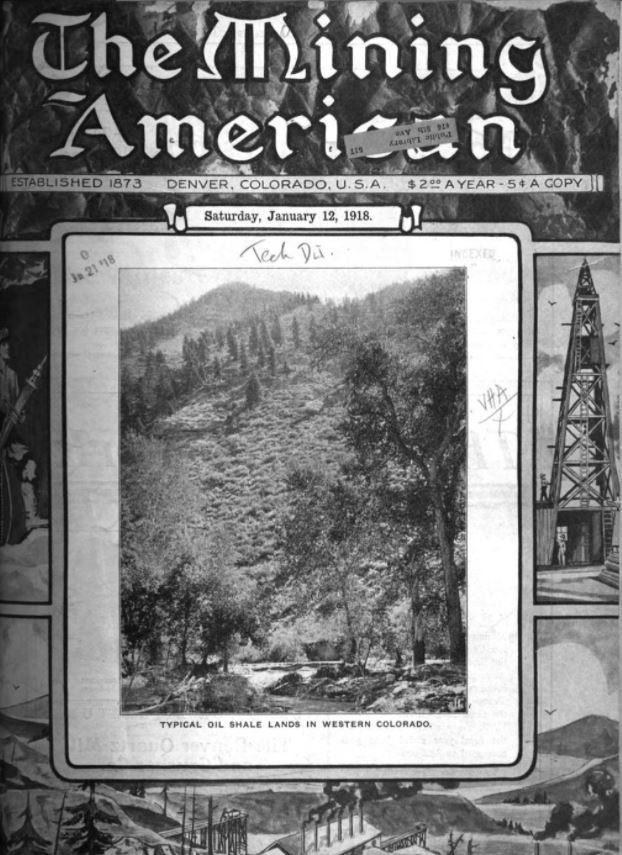

Citing earlier wells drilled by the Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company, Mining American magazine in 1918 noted, “Possibilities of Greater Production in Boulder Oil Fields,”

The first three wells of Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas produced enough oil to support more drilling in the booming Boulder field. After production peaked in 1909 at more about 85,000 barrels of oil, some people would claim Boulder made Colorado oil history as, “one of the wildest, crookedest, and most disastrous booms.”

Local historian Silvia Pettem summarized, “Although the oil under the land northeast of Boulder was real, no amount of drilling could keep up with inflated expectations. In just a few months, the bottom fell out of the market.”

Although C.B. Younglove and T.F. Little’s Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company would fade away, by World War I, Mining American magazine teased speculative investors with “Possibilities of Greater Production in Boulder Oil Fields” (January 5, 1918), citing the exploratory wells of Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas. The magazine proclaimed, “Recent Survey Encourages Deeper Drilling…Younglove Well Commended by Expert.”

But the Boulder boom was already part of U.S. petroleum history. So was Savannah Oil, Coal, and Gas Company.

The first commercially successful Colorado oil well was drilled in January 1862 near the mining supply town of Cañon City, about 45 miles southwest of Colorado Springs. The well produced oil just three years after the first U.S. oil well, which was drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania, by Edwin L. Drake for the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1860, businessman Gabriel Bowen had established what many consider Colorado’s first oil venture, the G. Bowen & Company. Bowen claimed ownership of natural oil seeps at Oil Spring — above what would later prove to be the Florence oilfield.

However, Bowen’s claim, “apparently was jumped in the winter of 1860-61 by J.L. Dunn, who dug four pits at the spring,” according to Colorado Encyclopedia. “One of the pits produced a barrel per day, but the others yielded little. Dunn left the area in early 1861, after being charged with cattle rustling.”

Although Bowen regained control of Oil Spring, Alexander Cassidy bought the claim in January 1862 and formed the Colorado Oil Company, “the state’s first commercially productive oil enterprise,” the encyclopedia noted in 2021. Cassidy’s well produced “at most a few barrels per day, which the company sold in Cañon City, Denver, and Santa Fe.”

With wells reaching a depth of 1,445 feet by the 1890s, production in Colorado’s Florence oilfield would peak at more than 3,000 barrels of oil per day.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Geology of the Boulder district, Colorado: USGS Bulletin 265 (2013); High Altitude Energy: A History of Fossil Fuels in Colorado (2002). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploring Boulder Oilfield History.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: August 6, 2022. Original Published Date: August 24, 2021, 2021.

To view this protected post, enter the password below: