by Bruce Wells | Jun 5, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Oilfield production technologies began in Pennsylvania with an economical way to pump multiple wells.

In the earliest days of the petroleum industry, which began with an 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, production technologies used steam power and a walking beam pump system that evolved into ways for economically producing oil from multiple wells.

Just as drilling technologies evolved from spring poles to steam-powered cable tools to modern rotary rigs, oilfield production also improved.

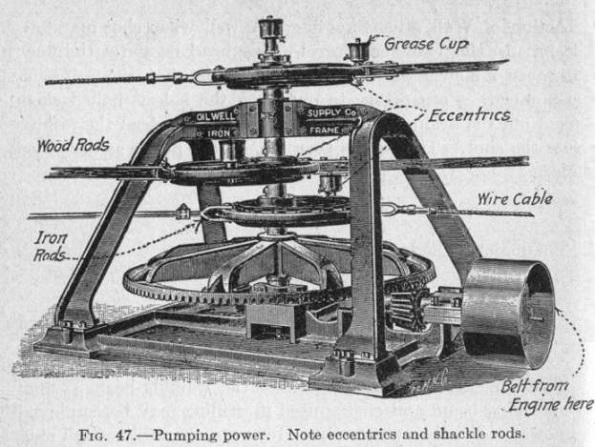

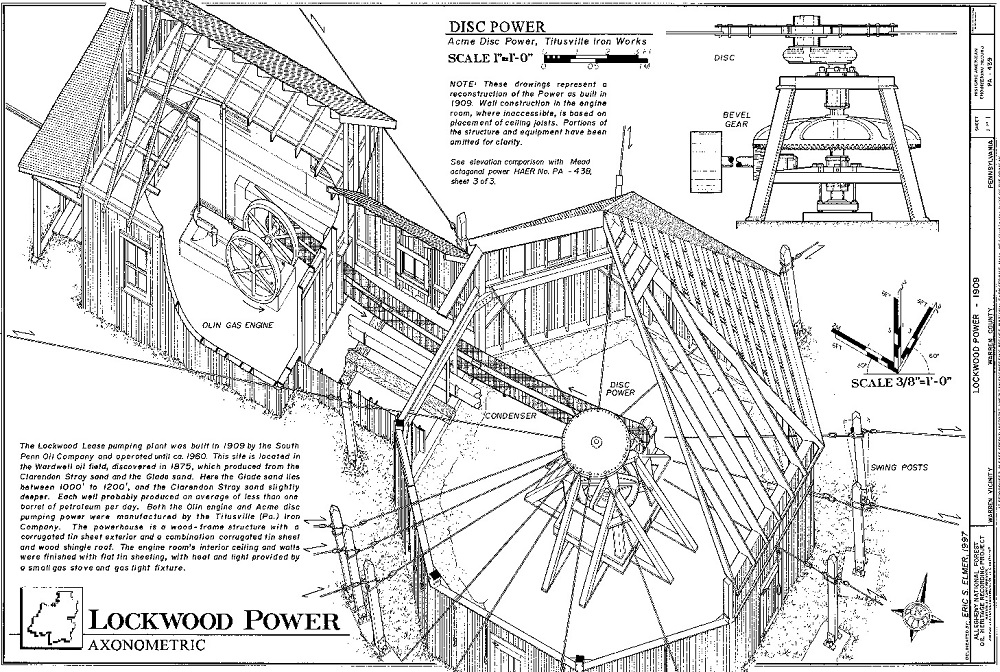

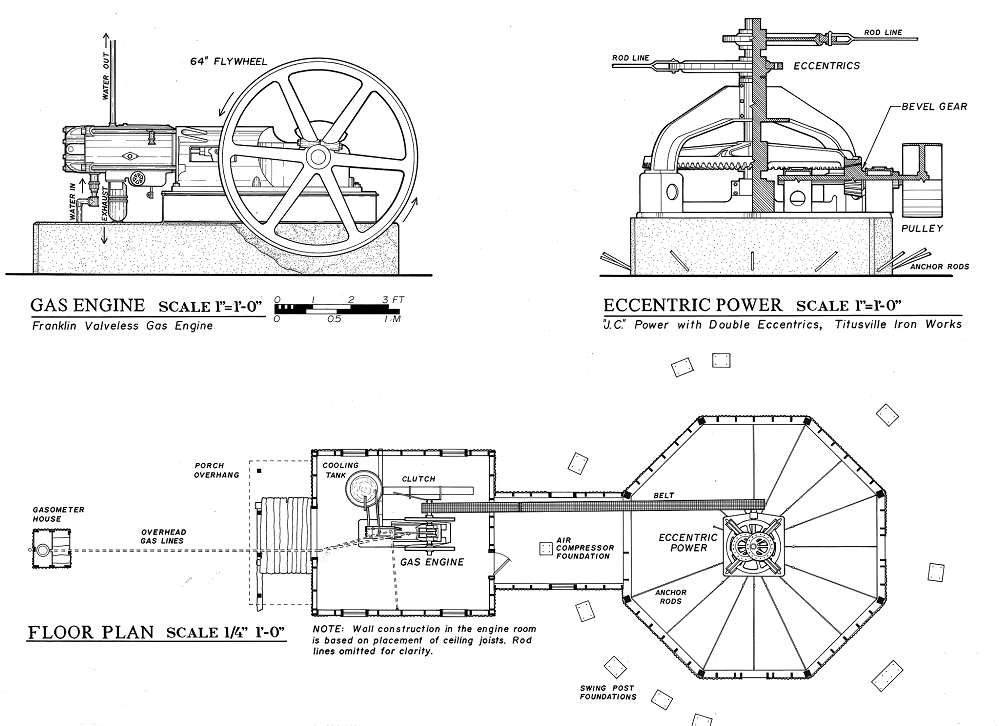

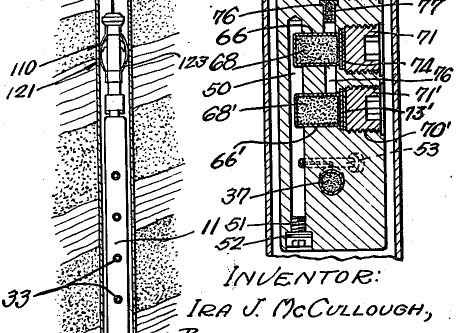

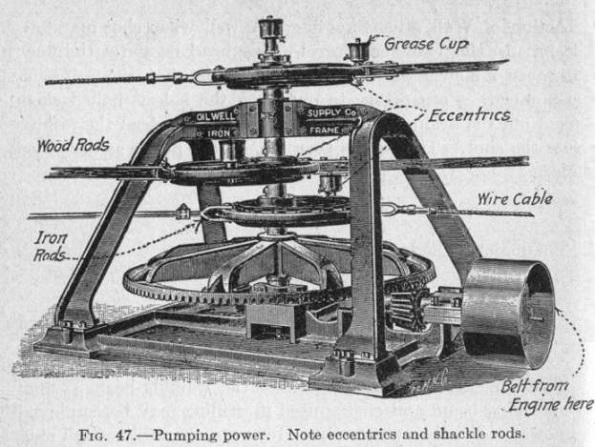

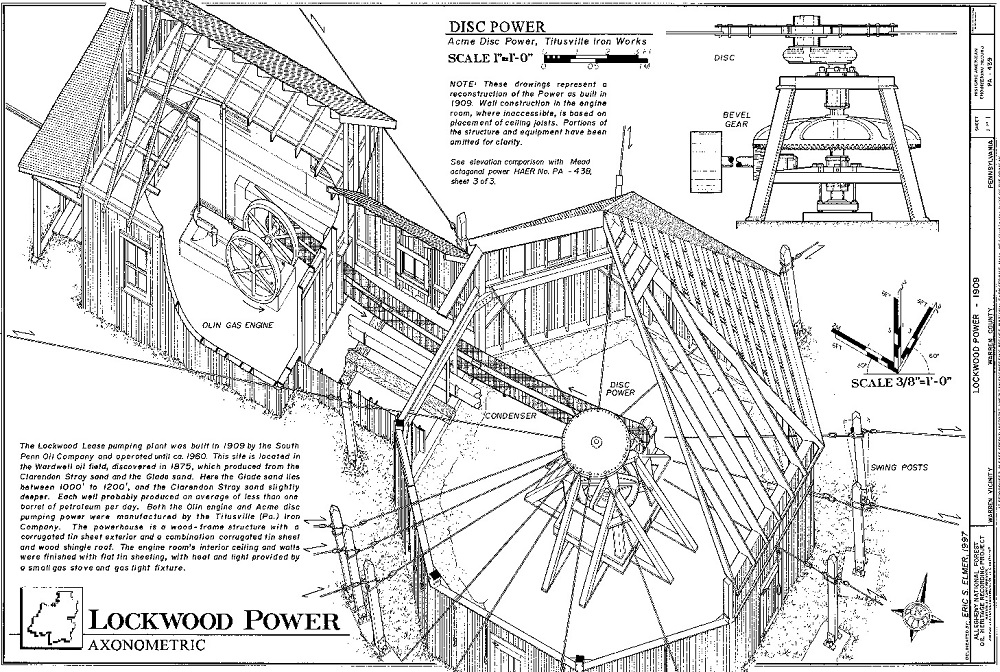

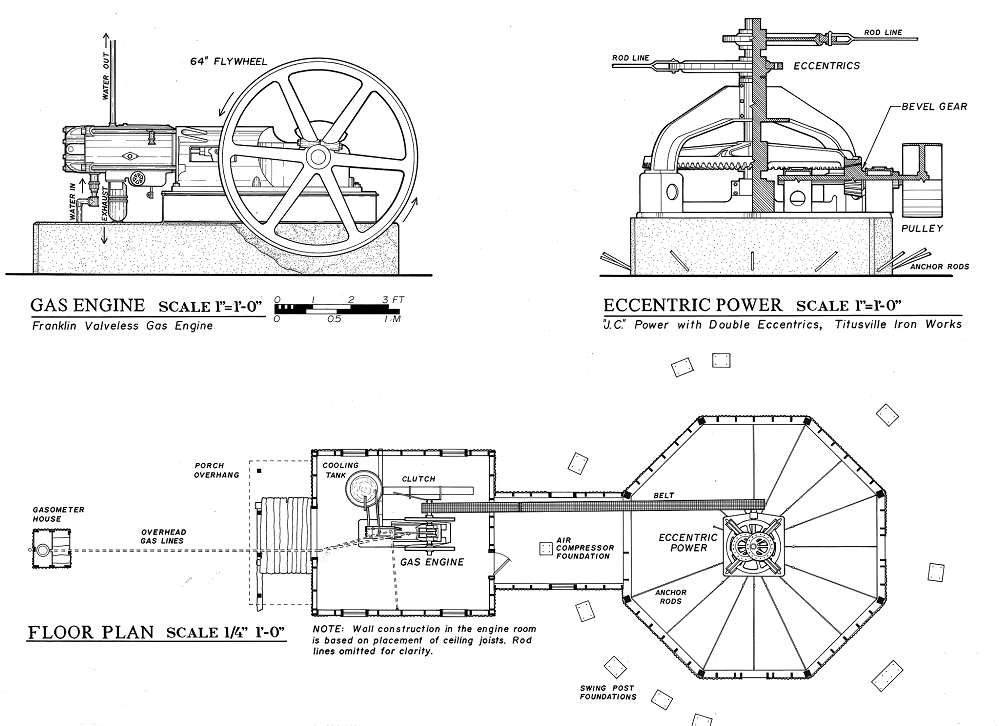

This image of a circa 1909 double eccentric power wheel manufactured by the Titusville (Pennsylvania) Iron Works is just one example of what can be discovered online at public domain resources. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Collections.

In the early days of the industry, oil production technology used steam power and a wooden walking beam. A steam engine at each well raised and lowered one end of the beam. An oil production technique perfected in Pennsylvania used central power for pumping low-production wells to economically recover oil.

Eccentric Wheels

A Library of Congress (LOC) photograph from 1909 shows a “double eccentric power wheel,” part of an innovative centralized power system. The oilfield technology from a South Penn Oil Company (the future Pennzoil) lease between the towns of Warren and Bradford, Pennsylvania.

The LOC photograph preserves the oilfield technology that used the two wheels’ elliptical rotation for simultaneously pumping multiple oil wells. The wheels’ elliptical rotation simultaneously pumped eleven remote wells. This central pump unit operated in the Morris Run oilfield, discovered in 1883. It was manufactured at the Titusville Iron Works.

Many oilfield history resources can be found in the Library of Congress Digital Collections and the related images of petroleum history photography. The development of centralized pumping systems — eccentric wheels and jerk lines — often are preserved in high-resolution files.

The Morris Run field in Pennsylvania produced oil from two shallow “pay sands,” both at depths of less than 1,400 feet. It was part of a series of other early important discoveries.

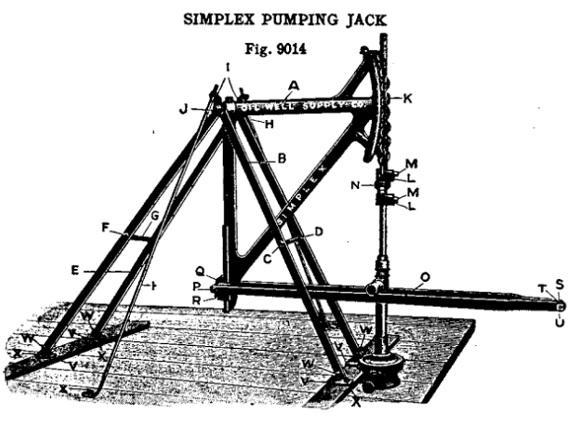

Late 18th-century Oil Well Supply Company illustration of pumping system using rods, cables, and an eccentric wheel.

In 1881, the Bradford field alone accounted for 83 percent of all the oil produced in the United States (see Mrs. Alford’s Nitro Factory). In 2004, new technologies began producing natural gas from a far deeper formation, the Marcellus Shale.

Oil production from some of the earliest shallow Pennsylvania wells declined to only about half a barrel of oil a day, but some continued pumping into 1960. On the West Coast, a 1913 central pumping unit produced from California’s largest oilfield three decades longer.

Midway-Sunset Jack Plant

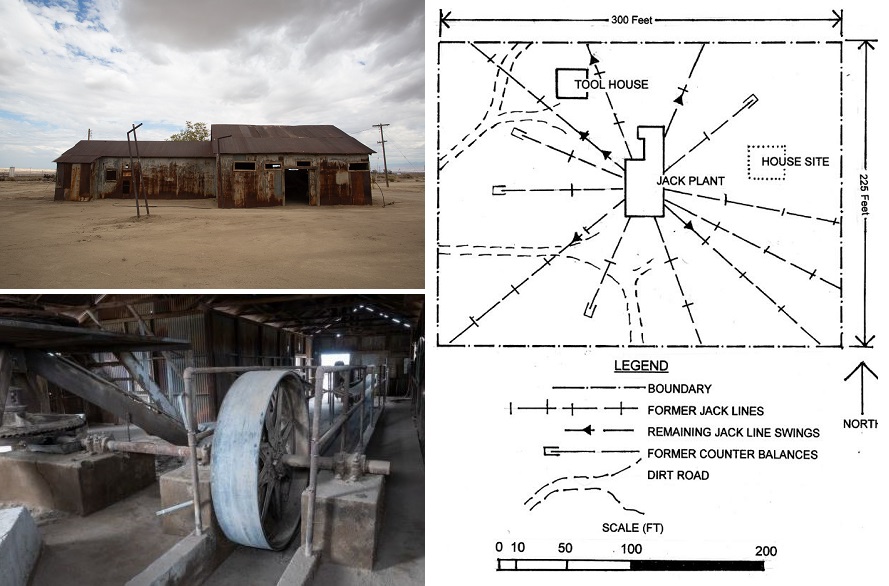

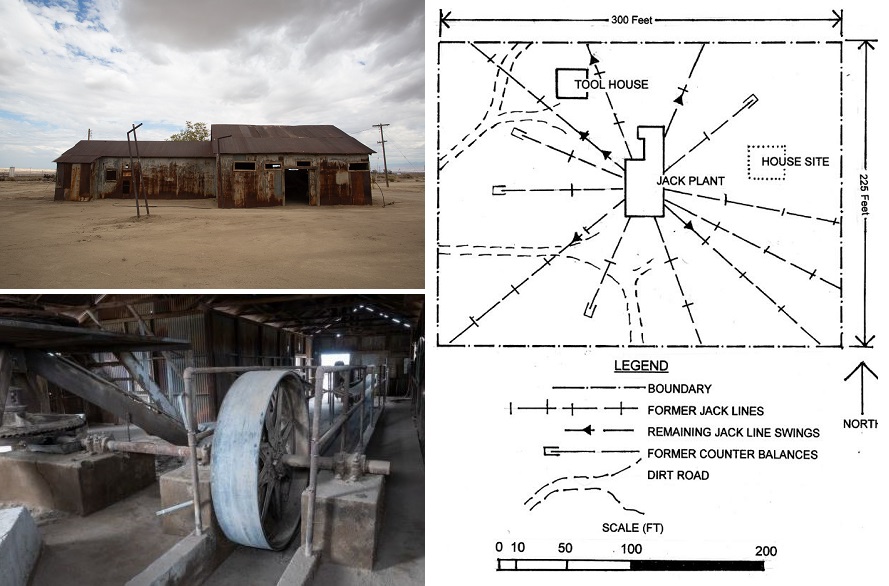

On June 9, 2023, the National Park Service added the Midway-Sunset Jack Plant to the National Register of Historic Places — thanks to Mark Smith, who submitted the application to preserve the facility. Installed by the Engineers Oil Company in 1913, the Kern County jack plant pumped oil until 1990.

In operation until 1990, California’s Midway-Sunset Jack Plant used eccentric-wheel technologies from the late 19th century. The Kern County plant pumped more than 1.5 million barrels of oil. Photos courtesy John Harte. Illustration courtesy San Joaquin Geological Society.

“The Midway-Sunset Jack Plant is an extremely rare example of central power and ‘jack-line’ oil pumping technology on its original site and housed in its original building,” Smith noted in his 45-page draft application to the State Historical Resources Commission. “Its design and operational history reflect significant advancements in oil extraction technology.”

According to company records, the jack plant’s slowly rotating eccentric wheels produced 1.5 million barrels of oil during its lifetime. The end came when the bearing of the vertical shaft became worn, causing the shaft to wobble. The wobble of the eccentric gears made the pumping of the wells out of balance.

Pumping Multiple Wells

As the number of oil wells grew in the early days of America’s petroleum industry in Pennsylvania, simple water-well pumping technologies began to be replaced with steam-driven walking-beam pumping systems.

At first, each well had an engine house where a steam engine raised and lowered one end of a sturdy wooden beam, which pivoted on the cable-tool well’s “Samson Post.” The walking beam’s other end cranked a long string of sucker rods up and down to pump oil to the surface.

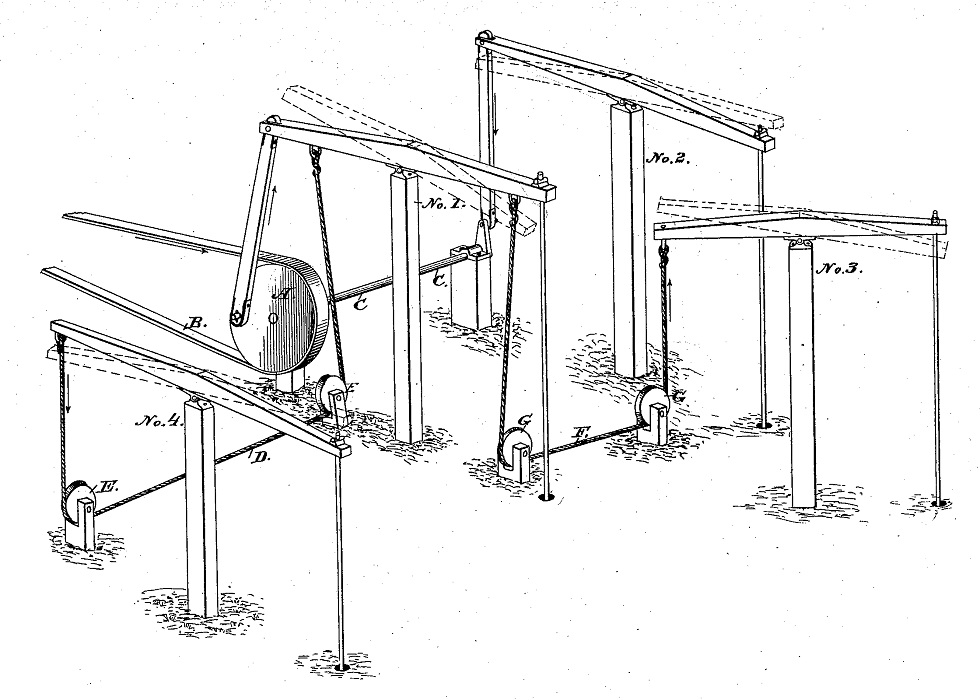

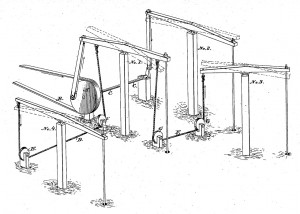

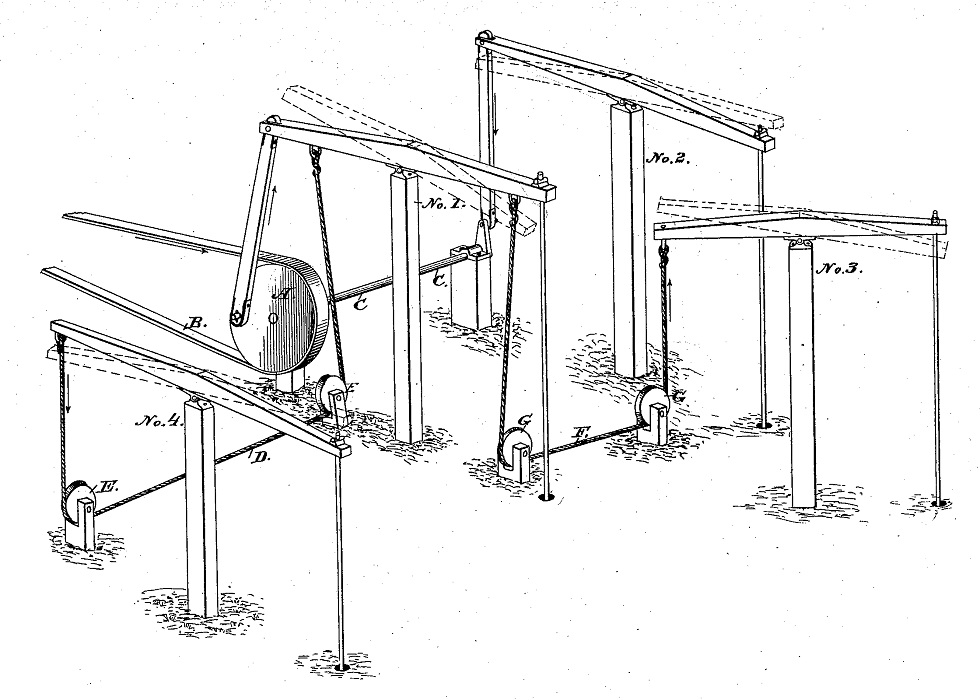

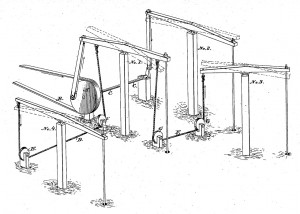

America’s oilfield technologies advanced in 1875 with this “Improvement In Means For Pumping Wells” invented in Pennsylvania.

Recognizing that pumping multiple wells with a single steam engine would boost efficiency, on April 20, 1875, Albert Nickerson and Levi Streeter of Venango County, Pennsylvania, patented their “Improvement in Means for Pumping Wells.”

Their system was the forerunner of wooden or iron rod jerk line systems for centrally powered oil production. This technology, eventually replaced by counter-balanced pumping units, will operate well into the 20th century – and remain an icon of early oilfield production.

“By an examination of the drawing it will be seen that the walking beam to well No. 1 is lifting or raising fluid from the well. Well No. 3 is also lifting, while at the same time wells 2 and 4 are moving in an opposite direction, or plunging, and vice versa,” the inventors explained in their patent application (No. 162,406).

Central Power Units

“Heretofore it has been necessary to have a separate engine for each well, although often several such engines are supplied with steam from the same boiler,” noted Nickerson and Streeter.

“The object of our invention is to enable the pumping of two or more wells with one engine…By it the walking beams of the different wells are made to move in different directions at the same time, thereby counterbalancing each other, and equalizing the strain upon the engine.”

An Allegheny National Forest Oil Heritage Series illustration of an oilfield “jack plant” in McKean County, Pennsylvania.

Steam initially drove many of these central power units, but others were converted to burn natural gas or casing-head gas at the wellhead – often using single-cylinder horizontal engines. Examples of the engines, popularly called “one lungers” by oilfield workers, have been collected and restored (see Coolspring Power Museum).

Many widely used techniques of drilling and pumping oil were developed to recover the high-quality “Pennsylvania Grade” oil. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

The heavy and powerful engine — started by kicking down on one of the iron spokes — transferred power to rotate an eccentric wheel, which alternately pushed and pulled on a system of rods linked to pump jacks at distant oil wells.

Pump Jacks

“Transmitting power hundreds of yards, over and around obstacles, etc., to numerous pump jacks required an ingenious system of reciprocating rods or cables called Central Power and jerker lines,” explains documentation from an Allegheny National Forest Oil Heritage Series.

The series documentation includes an early illustration of an oilfield “jack plant” in McKean County, Pennsylvania. The long rod lines were also called shackle lines or jack lines.

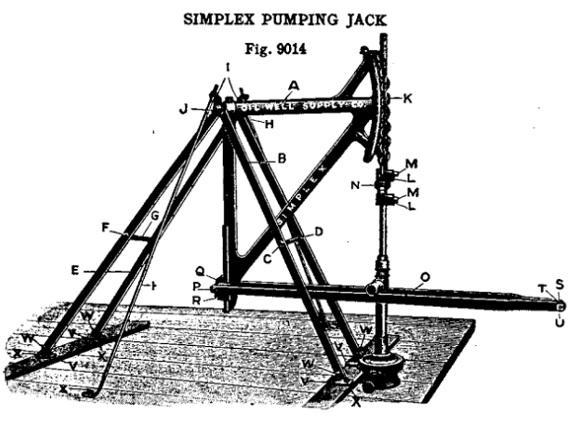

A single engine with eccentric wheel connecting rod lines could economically pump oil using Oil Well Supply Company’s “Simplex Pumping Jacks.”

Around 1913, with electricity not readily available, the Simplex Pumping Jack became a popular offering from Oil Well Supply Company of Oil City, Pennsylvania. The simple and effective technology could often be found at the very end of long jerk lines.

A central power unit could connect and run several of these dispersed Simplex pumps. Those equipped with a double eccentric wheel could power twice as many.

Roger Riddle, a retired field guide for the West Virginia Oil & Gas Museum in Parkersburg, grew up around central power units and recalls the rhythmic clanking of rod lines.

Riddle guided visitors through dense nearby woods where remnants of the elaborate systems rust. The heavy equipment once “pumped with just these steel rods, just dangling through the woods,” he said. “You could hear them banging along – it was really something to see those work. The cost of pumping wells was pretty cheap.”

The heyday of central power units passed when electrification arrived, nonetheless, a few such systems remain in use today. Learn more about the evolution of petroleum production methods, the first counter-balanced “Nodding Donkeys” in All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology.

______________________

Recommended Reading: Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language (2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Eccentric Wheels and Jerk Lines.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/jerk-lines-eccentric-wheels. Last Updated: June 15, 2025. Original Published Date: November 20, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 14, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

April 14, 1865 – Failed Oilman turns Assassin –

After failing to make his fortune in Pennsylvania oilfields, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C. Booth had left his acting career a year earlier to drill an oil well in booming Venango County.

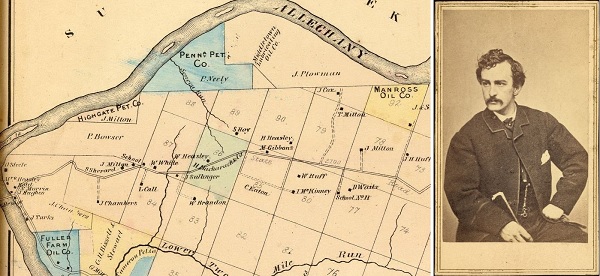

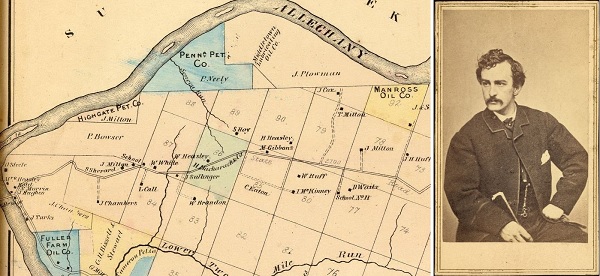

In January 1864, Booth visited Franklin, Pennsylvania, where he leased 3.5 acres on a farm, about one mile south of the village of Franklin and on the east side of the Allegheny River. With several partners, including his friends from the stage, Booth formed the Dramatic Oil Company and raised money to drill a well.

John Wilkes Booth made his first trip to the oil boom town of Franklin, Pennsylvania, in January 1864. He purchased a 3.5-acre lease on the Fuller farm (lower left). Circa 1865 photo of Booth by Alexander Gardner, courtesy Library of Congress.

Although the Dramatic Oil Company’s well found oil and began producing about 25 barrels a day, Booth and his partners wanted more and tried “shooting” the well to increase production. When the well was ruined, the failed oilman left the Pennsylvania oil region for good in July 1864.

Learn more in Dramatic Oil Company.

April 14, 1903 – Patent for Self-Heating Iron fueled by Gasoline

John Lake of Big Prairie, Ohio, received a U.S. patent (No. 725,261) for his gasoline-fueled “Self-Heating Sad Iron.” Lake had served in the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. The ironing innovation for homes brought prosperity to his Amish community, where he established the Monitor Sad Iron Company on the Pennsylvania Railroad line. His manufacturing company made the petroleum-fueled irons for the next 50 years.

Learn more in Ironing with Gasoline.

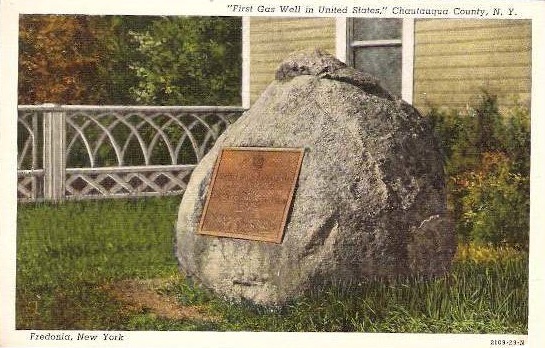

April 15, 1857 – First Natural Gas Company incorporated

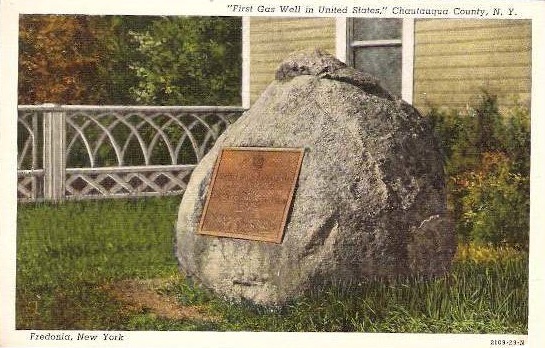

Two years before the first U.S. oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, the Fredonia Gas Light and Water Works Company incorporated in Fredonia, New York, where a well drilled by local machinist and gunsmith William A. Hart supplied natural gas to a mill as early as 1825. Hart found the gas after drilling three wells, according to historian Lois Barris.

“He left a broken drill in one shallow hole and abandoned a second site at a depth of forty feet because of the small volume of gas found,” Barris noted in her “Fredonia Gaslight and Waterworks Company.”

Circa 1950 souvenir postcard of a bronze plaque on a boulder in Fredonia, New York, dedicated in 1925 by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Hart’s third well produced natural gas from 70 feet beneath a “bubbling gas spring in the bed of a creek,” Barris reported, adding that after constructing a simple gasometer, he “proceeded to pipe and market the first natural gas sold in this country.”

As other communities adopted public lighting burning gas made from coal (manufactured gas street lamps began illuminating Baltimore in 1817), Fredonia Gas Light and Water Works built the first U.S. natural gas pipeline network.

April 15, 1897 – Birth of Oklahoma Oil Industry

With a crowd gathered at the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 well near Bartlesville in Indian Territory, George Keeler’s stepdaughter dropped a “Go Devil” that set off a downhole canister of nitroglycerin. The resulting gusher heralded the start of Oklahoma’s oil and natural gas industry.

A 2017 water gusher demonstration of the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 replica in Discovery One Park, Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

Drilling had begun in January 1897, the same month that Bartlesville incorporated with a population of about 200 people. Four months later, at 1,320 feet, the Nellie Johnstone No.1 well showed its first signs of oil. There had been earlier marginal producers, including a Cherokee Nation 1890 oil well; the Johnstone well revealed the giant Bartlesville-Dewey field.

By the time of statehood in 1907, Oklahoma would lead the world in oil production. An 84-foot derrick in Discovery One Park helps educate visitors about Oklahoma’s petroleum industry. The surrounding land was donated by Nellie Johnstone Cannon, the descendant of a Delaware chief.

Learn more in First Oklahoma Oil Well.

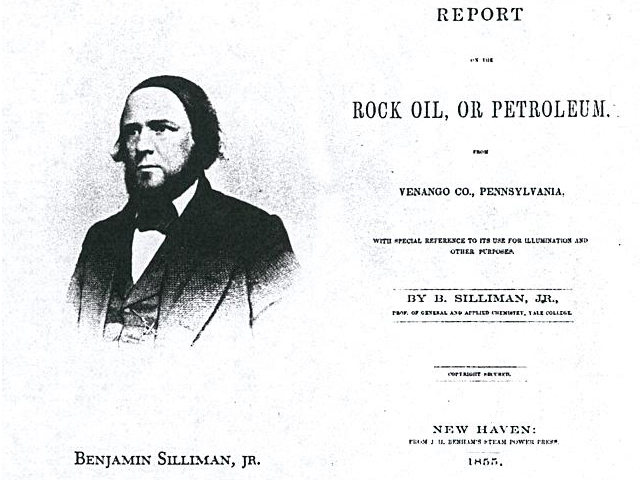

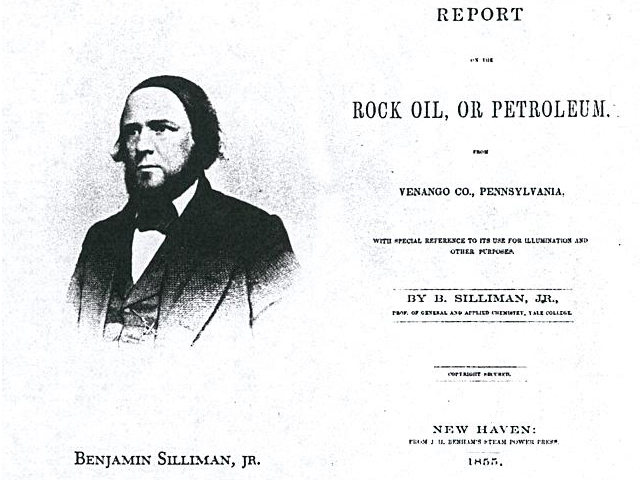

April 16, 1855 – Scientist sees Value in “Rock Oil”

Yale chemist Benjamin Silliman Jr. reported Pennsylvania “Rock Oil” could be distilled into a high-quality illuminating oil. The professor’s “Report on Rock Oil or Petroleum” convinced a businessman George Bissell and a group of New Haven, Connecticut, investors to finance Edwin Drake to drill where Bissell had found oil seeps at a creek in northwestern Pennsylvania.

The Yale chemist’s 1855 report about oil’s potential for refining as an illuminant led to America’s first commercial well four years later.

“Gentlemen,” Silliman wrote, “it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products.”

Learn more in George Bissell’s Oil Seeps.

April 16, 1920 – First Arkansas Oil Well

Col. Samuel S. Hunter of the Hunter Oil Company of Shreveport, Louisiana, completed the first oil well in Arkansas. His Hunter No. 1 well had been drilled to 2,100 feet. Natural gas was discovered a few days later by Constantine Oil and Refining Company north of what would become the El Dorado field in Union County.

The Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources is just north of El Dorado.

Although Col. Hunter’s oil well yielded only small quantities, his discovery was followed by a January 1921 gusher — the S.T. Busey well — in the same field. These wells made headlines and launched the Arkansas petroleum industry, according to the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources. Hunter later sold his original lease of 20,000 acres to the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana for more than $2.2 million.

Learn more in First Arkansas Oil Wells.

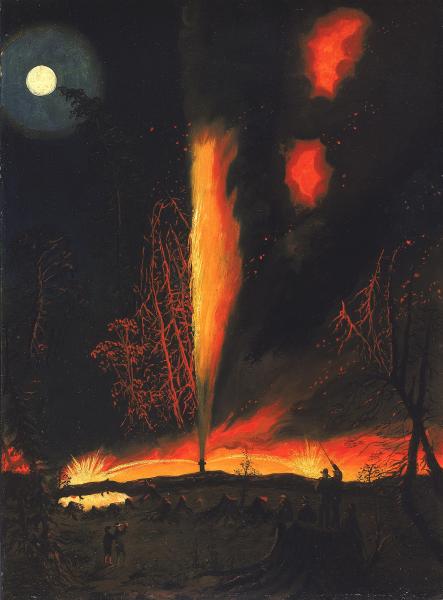

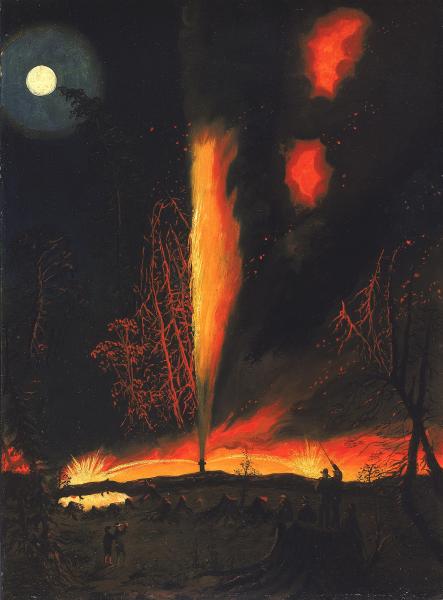

April 17, 1861 – Deadly Oil Well Fire in Pennsylvania

The lack of technologies for controlling wells led to a fatal oil well fire at Rouseville, Pennsylvania. Among the 19 people killed was leading citizen Henry Rouse, who subleased the land along Oil Creek. When his well erupted oil from a depth of 320 feet, the good news had attracted most Rouseville residents. “Henry Rouse and the others stood by wondering how to control the phenomenon,” noted the local newspaper. Then the gusher erupted into flames, perhaps ignited by a steam-engine boiler.

“Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” a painting by James Hamilton, circa 1861, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The oilfield tragedy near Titusville would be overshadowed by the Civil War, but it was immortalized in 1861 by Philadelphia artist James Hamilton’s “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” which was added to the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection in 2017.

Learn more in Fatal 1861 Rouseville Oil Well Fire.

April 17, 1919 – North Texas Burkburnett Boom grows

Yet another drilling boom began in Wichita County, Texas, when the Bob Waggoner Well No. 1 well began producing 4,800 barrels of oil a day — extending to the northwest a 1918 oilfield found on the Burkburnett farm of S.L. Fowler. Wichita County had been producing oil since the 1911 discovery of the Electra oilfield.

At Burkburnett, a 2006 historical marker of the Texas Historical Commission notes the 1919 discovery “became known as the Northwest Extension Oilfield, comprised of approximately 27 square miles on the former S. Burk Burnett Wild Horse Ranch.” The marker adds “the area was suddenly thick with oil derricks” thanks to the oilfield discoveries that created the boom town Burkburnett.

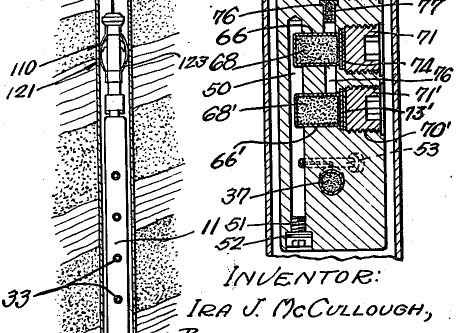

April 18, 1939 – Patent for perforating Well Casing

Ira McCullough of Los Angeles patented a multiple bullet-shot casing perforator and mechanical firing system. He explained the object of his oilfield invention was “to provide a device for perforating casing after it has been installed in a well in which projectiles or perforating elements are shot through the casing and into the formation.”

Ira McCullough’s 1937 patent drawing for perforating wells.

The innovation of simultaneous firing from several levels in the borehole greatly enhanced the flow of oil. McCullough’s device included a “disconnectable means” that rendered percussion inoperative until the charges were lowered into the borehole, acting as “a safeguard against accidental or inadvertent operation.”

Another inventor, Henry Mohaupt, in 1951 used anti-tank technology from World War II to improve the concept by using a conically hollowed-out explosive for perforating wells.

Learn more in Downhole Bazooka.

April 19, 1892 – First U.S. Gasoline Powered Automobile

Brothers Charles and Frank Duryea test drove a gasoline-powered automobile they had built in their Springfield, Massachusetts, workshop. Considered the first model to be regularly manufactured for sale in the United States, 13 were produced by the Duryea Motor Wagon Company.

The Duryea brothers (above) built their pioneering autos in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The brothers sold their first Duryea motor wagon in March 1918. Two months later, a motorist driving a Duryea in New York City hit a bicyclist — reportedly America’s first auto traffic accident. By the time of the first U.S. automobile show in November 1900 at Madison Square Garden, of the 4,200 automobiles sold in the United States, gasoline powers less than 1,000.

April 20, 1875 – Improved Well Pumping Technology

Pumping multiple wells with a single steam engine boosted efficiency in early oilfields when Albert Nickerson and Levi Streeter of Venango County, Pennsylvania, patented their “Improvement In Means For Pumping Wells.” The new technology used a system of linked and balanced walking beams to pump oil wells.

U.S. oilfield technologies advanced in 1875 with an “Improvement In Means For Pumping Wells.”

“By an examination of the drawing it will be seen that the walking-beam to well No. l is lifting or raising fluid from the well. Well No. 3 is also lifting, while at the same time wells 2 and 4 are moving in an opposite direction, or plunging, and vice versa,” the inventors explained. Their system was the forerunner of rod-line (or jerk-line) eccentric wheel systems that operated into the 20th century using iron rods instead of rope and pulleys.

Learn more in All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology.

April 20, 1892 – Prospector discovers Los Angeles City Oilfield

The giant Los Angeles oilfield was discovered when a struggling prospector, Edward Doheny, and his mining partner Charles Canfield drilled into the tar seeps between Beverly Boulevard and Colton Avenue. Their well produced about 45 barrels of oil a day.

Artfully camouflaged petroleum production continues today in downtown Los Angeles. Edward Doheny discovered the oilfield in 1892. Photo courtesy the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Culver City, California.

Although the first California oil well had been drilled after the Civil War, Doheny’s 1892 discovery near present-day Dodger Stadium launched California’s petroleum industry. In 1897, about 500 Los Angeles City wells pumped more than half of the state’s annual production of 1.2 million barrels of oil. By 1925, California supplied half of all the world’s oil.

Learn more in Discovering Los Angeles Oilfields.

April 20, 2010 – Deepwater Horizon Gulf of Mexico Disaster

At 10 a.m., while completing a well in the Macondo Prospect, 50 miles off the Louisiana coast, the Deepwater Horizon exploded and sank, killing 11 and injuring another 17 workers. An estimated 3.2 million barrels of oil flowed into the Gulf of Mexico after the platform’s 400-ton blowout preventer failed, resulting in the largest accidental marine oil spill in U.S. history.

The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion and fire killed 11 and injured 17 workers. USGS Photo.

Six months earlier at another site, the advanced, semi-submersible drilling rig had set a world record for the deepest offshore well (35,050 feet vertical depth in 4,130 feet of water). When the Macondo Prospect well was capped in mid-July, a National Commission on the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling launched an eight-month investigation. The commission released its final report on January 11, 2011.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Recommended Reading: Sketches in Crude-Oil (1902); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Oil in Oklahoma

(2009); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Oil in Oklahoma (1976); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1976); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania (2000); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(1982); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania (2000); Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields

(2000); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields (1990); Dark Side of Fortune: Triumph and Scandal in the Life of Oil Tycoon Edward L. Doheny (2001); Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling: Report to the President

(1990); Dark Side of Fortune: Triumph and Scandal in the Life of Oil Tycoon Edward L. Doheny (2001); Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling: Report to the President (2011). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2011). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

(2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.