Finding oil near natural seeps in Indian Territory.

Drilled near petroleum seeps in 1889 and completed one year later southwest of Chelsea in Indian Territory, the story of Edward Byrd’s oil well in the Cherokee Nation is not as well known as the “Bartlesville gusher” of 1897, the official first Oklahoma oil well.

What would become known as the Indian Territory began when President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The legislation established a process where the president could forcibly relocate native American tribes westward.

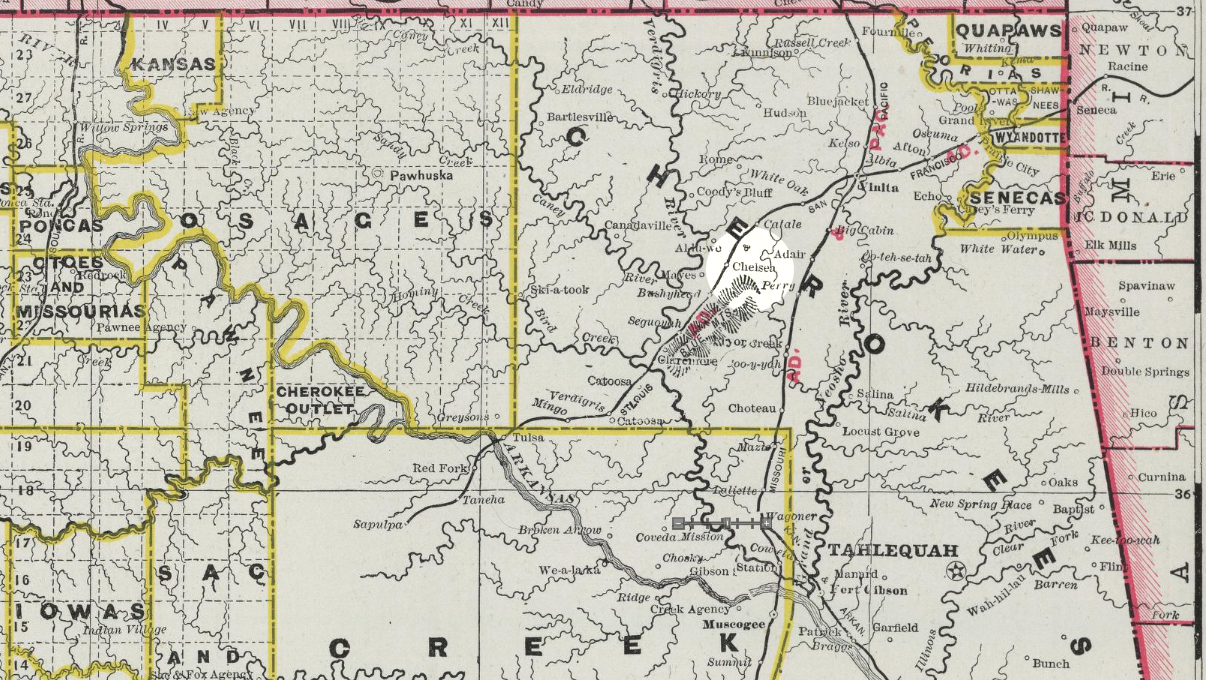

Chelsea began in 1881 as a railroad stop in the Cherokee Nation. Its oil well was drilled in 1889 and completed a year later, producing half a barrel of oil per day from 36 feet deep.

Land “remote from white settlements” west of Arkansas was deemed the best place to settle the tribes, according to The Five Civilized Tribes: Indian Territory, a 1900 article in the annual Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York (vol. XXXII).

Title and deed gave ownership of the land to the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, and Cherokee where they could establish tribal governments under the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“It was intended to settle them there for all time, whereby they could live to themselves, according to their own pleasure, with self-government, under the protection of the general Government,” notes C.H. Fitch, author of the Journal article.

However, westward growth and legislation such as the Dawes Act (1887) and Curtis Act (1898) ultimately stripped the tribal governments of their authority. Their designated tribal lands were reduced from about 150 million acres to 78 million acres as America’s search for petroleum reached into Indian Territory.

Oil in Indian Territory

In 1882, Edward Byrd, a Cherokee by marriage, found oil seeps southwest of Chelsea in Indian Territory. Two years later, the Cherokee Nation passed a law authorizing the organization of a company “for the purpose of finding petroleum, or rock oil, and thus increasing the revenue of the Cherokee Nation.”

Seven years earlier than a headline-making 1897 gusher at Bartlesville in the Cherokee Nation, the United States Oil and Gas Company completed an oil well at Chelsea, about 35 miles southeast.

Leases were limited to Cherokee citizens, and in 1887 Byrd organized the United States Oil and Gas Company with his partner William B. Linn of Pennsylvania, home of the first U.S. oil well of 1859. The company had a contingent of four Kansas investors, William Woodman, Finley Ross, Oak Daeson and Martin Hellar.

Byrd’s petroleum exploration venture secured a 100,000-acre lease from the Cherokee Nation west of Chelsea, between the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway and the Verdigris River. The lease covered portions of present-day Rogers and Nowata counties in Oklahoma.

In 1890, United States Oil and Gas completed its first well on Spencer Creek, within yards of Byrd’s old oil seeps, using basic technologies for “making hole.” This Indian Territory well produced oil seven years before the Bartlesville well — but just half a barrel of oil a day from 36 feet deep.

Ten more marginal wells followed, and by the last quarter of 1891, the company reported a total of “twelve barrels of oil pumped” in what became the Chelsea-Alluwe field.

With little production and no large commercial market nearby, Byrd’s venture shut down. He then organized a group of Cherokee citizens into the Hugh B. Henry and Company and secured additional leases covering thousands of acres for United States Oil and Gas.

Cherokee Oil and Gas

John B. Phillips, an experienced independent oil producer from Butler, Pennsylvania, formed Cherokee Oil and Gas Company to take over United States Oil and Gas properties.

Under federal law, the leases had to be approved by the Department of the Interior, which reduced the size from more than 100,000 acres to 12,000 acres. Cherokee Oil and Gas also bought the 11 shallow, marginal wells of United States Oil and Gas wells for “twenty-five cents on the dollar.”

Cherokee Oil and Gas drilled deeper wells and found high-grade oil in two wells (1,450 feet deep and 1,320 feet deep) before a boiler explosion shut both wells down. Other small producing wells followed as the company continued drilling.

Meanwhile, another Indian Territory company explored near Bartlesville oil seeps, about 40 miles west. On April 15, 1897, the Cudahy Oil Company “shot” with nitroglycerin the company’s Nellie Johnstone No.1 well after finding signs of oil in March. This oilfield discovery well began producing up to 75 barrels of oil a day from 1,320 feet deep.

Despite the production, Cudahy Oil was confronted with a lack of infrastructure for moving oil to markets. With no storage tanks, pipelines or railroads available, the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 was capped for two years.

In 1898, Congress passed the Curtis Act, “for the Protection of the People of Indian Territory.” The new law, amending the Dawes Act of 1887, is described by the Oklahoma Historical Society as “the culmination of legislation designed to strip tribal governments of their authority and give it to Congress and/or the federal government.”

In Indian Territory oilfields, operations were brought to a standstill because of difficulties with titles, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. “The title of the oil and minerals remains in trust with the United States Government under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, who must ratify every lease to make it valid.”

The legislation also stipulated, “The amount of 640 acres can only be acquired by a single individual or company.”

An 1890 marginal producing well at Chelsea could be considered Oklahoma’s first petroleum production.

However, both the Cherokee Oil and Gas Company and the Cudahy Oil Company had leased more than 300,000 acres from the Cherokee Nation before the Curtis Act. Congressional hearings and litigation followed.

In 1902, the Superior Court of the District of Columbia upheld “the power of the Secretary of the Interior to lease Cherokee oil lands,” in litigation over a lease of 12,000 acres held by the Cherokee Oil and Gas Company. Cudahy Oil’s prospects were profoundly affected as well.

In 1904, the Los Angeles Herald reported on the pending merger of Cherokee Oil and Gas Company with Cudahy Oil Company to form a new combined enterprise, the Cudahy Pipe Line and Refining Company.

The merger never took place, although the combined assets reportedly amounted to 137 producing wells on the Cherokee Oil and Gas property and 87 producing wells on Cudahy leases for a total production of 2,100 barrels of oil a day.

“The producers are rather chary about signing up with the Cudahy concern,” noted the Weekly Examiner of Bartlesville in 1905. “An effort is being made to sell stock to the producers, but it is said the latter are not falling over each other in an effort to get on the independent band wagon.”

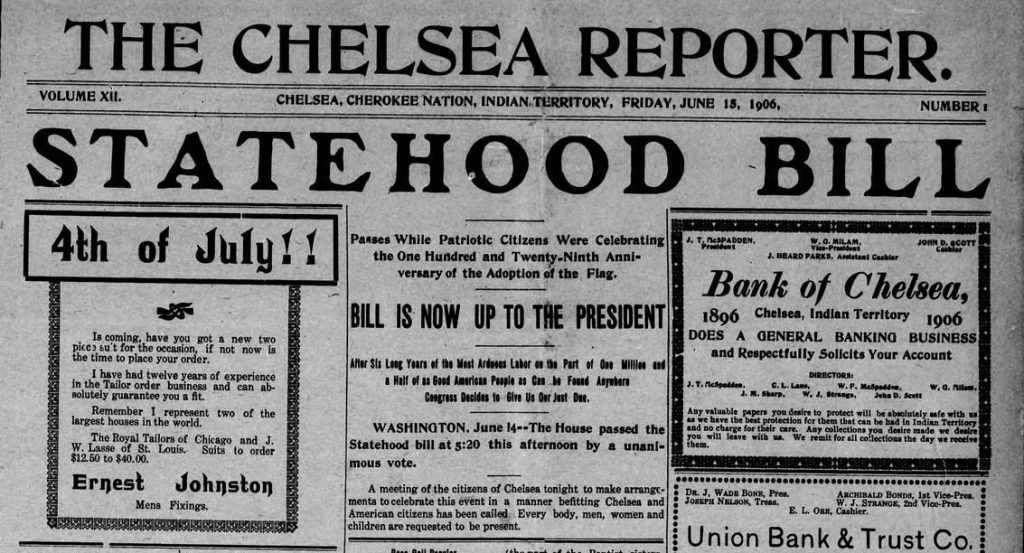

With the Curtis Act having cleared the last impediment to statehood, Oklahoma became the 46th state on November 16, 1907. Cherokee Oil and Gas Company continued to operate and by 1918, the company owned half-interest in 375 oil wells at Chelsea.

Old Faucett Well

Although the 1890 marginal oil producer at Chelsea could be called Oklahoma’s first, records show that in the Choctaw Nation, a well was completed by Dr. H.W. Faucett and Choctaw Oil and Refining Company.

The well drilled in the Choctaw Nation also has a claim to the “first Oklahoma oil well” title. The discovery on Choctaw land reached 1,400 feet deep, where it produced some oil — but not in commercial quantities. The “Old Faucett Well” of 1890 was abandoned after Dr. Fawcett fell ill and died later that year.

The Cherokee-Warren Oil and Gas Company (incorporated on March 31, 1919) took over the remaining assets of Faucett’s Choctaw Oil and Refining Company, the venture that had drilled another of Oklahoma’s first oil wells.

However, the 1897 gusher at Bartlesville officially remains the Sooner State’s first oil well. A replica cable-tool derrick of the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 can be found at Discovery 1 Park in Bartlesville. The wooden, 84-foot derrick produces a popular water-gushing demonstration among other petroleum exhibits, including an oilfield firefighting cannon.

__________________________

Recommended Reading: Oil in Oklahoma (1976); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma

(2013); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(1980); Conoco: 125 Years of Energy

(2000); Phillips, The First 66 Years

(1983). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

__________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Another First Oklahoma Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K. L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/another-first-oklahoma-oil-well. Last Updated: March 31, 2025. Original Published Date: March 9, 2017.