Oregon Wildcatters

Three petroleum exploration companies risked everything on one well in their gamble to to find an Oregon oilfield.

The lure of petroleum wealth invited speculators practically since the first U.S. oil well of 1859 in Pennsylvania. Exploratory wells especially have remained a high-risk investment since almost nine out of ten of these “wildcat” wells fail to produce commercial amounts of oil.

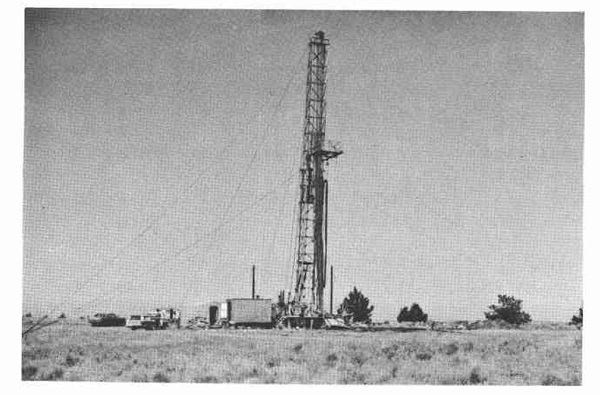

The Morrow No. 1 well, an ill-fated wildcat well first drilled in 1952 in Jefferson County, Oregon. Photo courtesy Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, “The Ore Bin,” Vol. 32, No.1, January 1970.

With under-capitalized operations turning to public sales of stock to raise money, many small ventures have been forced to bet everything on drilling a first successful well to have a chance at a second. Drilling a producing well can bring some wealth, but a “dry hole” brings bankruptcy.

And so it was in the 1950s on a remote hillside in Jefferson County, Oregon, where three companies searched for riches from the same well.

Northwestern Oils Inc.

The first of these three Oregon wildcatters, Northwestern Oils, incorporated in 1951 with $1 million capitalization in order to “carry on business of mining and drilling for oil.”

With offices in Reno, Nevada, in early 1952 Northwestern Oils began drilling a test well about eight miles southeast of Madras, Oregon. Using a cable-tool drilling rig (see Making Hole – Drilling Technology), drillers reached a depth of 3,300 feet on the Baycreek anticline before work was suspended because of “lost circulation troubles.”

Circulation troubles continued with the Morrow No. 1 well – also known as the Morrow Ranch well – in Jefferson County (Section 18, Township 12 South, range 15 East). By March 1956, with no money and no additional drilling possible, Northwestern Oils’ assets were “seized for non-payment of delinquent internal revenue taxes due from the corporation” and auctioned off at the Jefferson County courthouse.

Central Oils Inc.

Central Oils (Seattle) also was formed in 1956. With plans to join the other rare Oregon wildcatters, the company registered with the Security and Exchange Commission on July 30, 1958. It sought to sell one million shares of stock to the public at 10 cents a share. Proceeds would finance leasing and drilling, just like Northwestern Oils.

Central Oils received a permit to deepen Northwestern Oils’ old Morrow Ranch well in 1966 and planned to continue drilling with a cable-tool rig. Nothing happened.

“Commencement of this venture has been delayed until the spring of 1967,” one newspaper reported. But Central Oils had run afoul of the SEC. Oregon regulators recorded the well abandoned as of September 12, 1967, and Central Oils “out of business; no assets.”

Robert F. Harrison

In May 1968, Robert F. Harrison and his associates took over the same well — this time with plans to deepen it to more than 5,000 feet. But two years later the drilling effort was still stuck at a depth of 3,300 feet. Desperate, Harrison tried to clear the borehole by applying technologies for Fishing in Petroleum Wells.

On February 2, 1971, an intra-office report noted that R.F. Harrison “will abandon as soon as weather permits,” never having exceeded the original Northwestern Oils total depth of 3,300 feet. It would be a dry hole.

Harrison finally plugged and abandoned the Morrow No. 1 well as of October 12, 1971. Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries has identified the stubborn nonproducer as well number 36-031-00003. There has never been a successful oil well drilled in Oregon.

America’s first dry hole was drilled in 1859 by John Grandin of Pennsylvania – near and just a few days after the first commercial discovery. In 2014, U.S. oil wells produced more than 8.7 million barrels of oil every day, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil on the Brain: Petroleum’s Long, Strange Trip to Your Tank (2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration

(1979).

Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oregon Wildcatters.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/oregon-wildcatters. Last Updated: February 26, 2025. Original Published Date: January 29, 2016.