Joe B. Turman Oil Syndicate

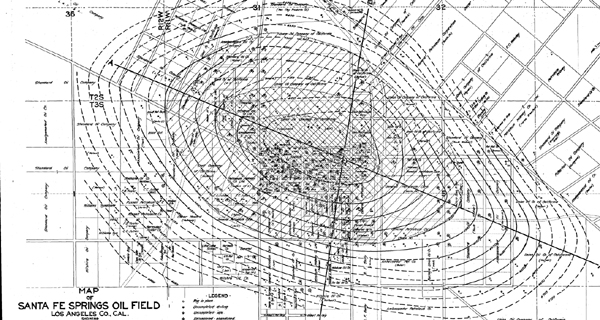

California became a major oil producing state in the 1920s thanks to oilfield discoveries including Signal Hill, Santa Fe Springs and Huntington Beach.

In November 1921, Union Oil Company completed a well producing 2,500 barrel of oil a day near Santa Fe Springs, California. The discovery at a depth of 3,763 feet prompted a flurry of speculation and leasing – especially because of a major discovery earlier that year a few miles to the south at Signal Hill.

By the start of 1922, 24 exploration companies were drilling at Santa Fe Springs – after scrambling to secure leases close to the Union Oil gusher (Section 5, Township 3 South, Range 11 West), today near the intersection of Telegraph Road and Bloomfield Avenue. By acting quickly to get close to proven production, these companies found it easier to interest investors.

Discovered by Union Oil Company in November 1921 near Los Angeles, the Santa Fe Springs oilfield attracted competing exploration companies.

That summer, Joe B. Turman had leased property in the adjacent Section 6 and launched his organization. To get in on the anticipated bonanza,Turman investors purchased “units,” each of which represented one five-thousandths (0.0002 percent) interest in the net proceeds of all oil and gas produced.

By August 1922 his company (also known as “Joseph/Jos. B Turman No. 2”) had secured sufficient funding and begun drilling in the new Santa Fe Springs oilfield. With one well underway and two more planned, sales of units remained critical. The California State Mining Bureau recorded monthly progress as Joe B. Turman’s rotary rig drilled deeper.

The Santa Ana Register of April 12, 1923, included a help wanted ad for sales agents: “Lady Solicitors Wanted To Represent Joe B. Turman Oil Syndicate in Orange and Santa Ana. Hustlers make big money, why not you?”

In March, the California Mining Bureau’s report declared, “The Santa Fe Springs field has a daily production equal to nearly one-half the entire production of the State of Oklahoma, California’s closest competitor for first honors in the production of petroleum.”

The Santa Fe Springs oilfield alone produced more than 81 million barrels in 1923. The production joined that from Signal Hill’s Long Beach field and the Huntington Beach oilfield.

The Eureka state’s natural oil seeps had attracted petroleum exploration companies since the first California oil well in 1876 and the discovery of the Los Angeles oilfields in 1893.

But despite Turman’s abundant unit sales, his drilling operation soon ran into technical difficulties. The Joe B. Turman No. 1 well got stuck at a depth of 3,660 feet – “frozen” in driller parlance of the time.

“When mudding through drill pipe, by circulation, the lower portion of the drill pipe is apt to be broken off, thereby causing a bad fishing job and endangering the hole…restricted mud circulation tends to freeze the drill pipe,” noted one expert about the process of fishing in petroleum wells.

It was the end of that well and plans for others as legal troubles began for the Joe B. Turman Oil Syndicate.

As court documents would later disclose, the syndicate had oversold its units in an “amount far in excess of the requirements of the drilling contract, and even far in excess of the total issue authorized.”

Officers reportedly “converted large sums to their own use,” the court documents noted, agreeing with a jury’s finding “that the whole scheme was conceived in fraud and was consummated through the misuse of the mail.”

On April 14, 1924, Turman was fined $50,000 and sentenced to three years in the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________