by Bruce Wells | Jan 9, 2026 | Petroleum Art

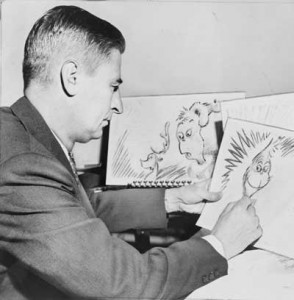

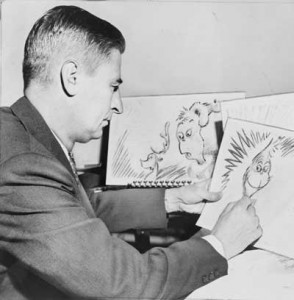

Theodor Seuss Geisel created many of his zoological oddities working for Standard Oil Company in the 1930s.

Dr. Seuss the oilman? Thirty years before the Grinch stole Christmas in 1957, many strange and wonderful critters of the popular children’s book author could be seen in Standard Oil Company advertising campaigns.

During the Great Depression, fanciful Dr. Seuss creatures promoted Essolube and other products for Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. Theodor Seuss Geisel would acknowledge his experience at Standard Oil “taught me conciseness and how to marry pictures with words.”

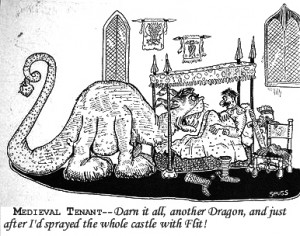

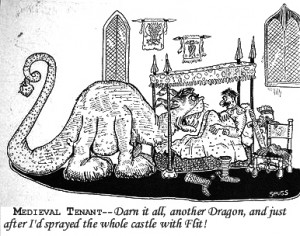

In the cartoon that launched his career, Geisel drew a peculiar dragon inside a castle. The January 14, 1928, issue of New York City’s Judge magazine featured the scaled beast. Geisel would introduce many less threatening characters inhabiting his imaginative menagerie.

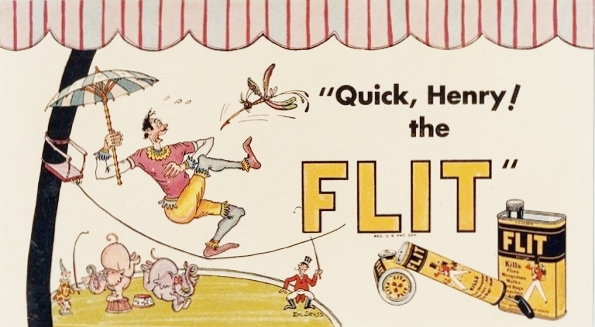

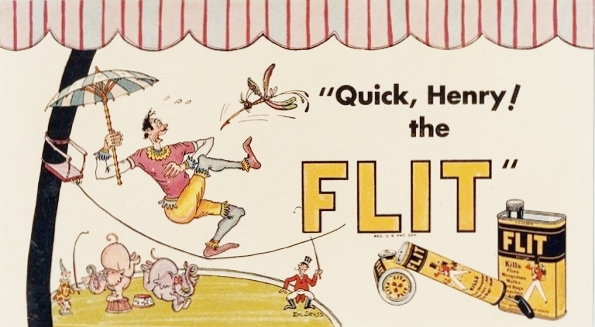

“Flit” was a popular bug spray of the day — especially against flies and mosquitoes. It was one of many Standard Oil Company of New Jersey consumer products derived from oil and natural gas (also see petroleum products).

A 1927 cartoon by Theodor Seuss Geisel featured Standard Oil’s petroleum product “Flit,” a widely used bug spray.

Late in 1927, Standard Oil’s growing advertising department, which had focused on sales of Standard and Esso gasoline, lubricating oil, fuel oil, and asphalt, reorganized to promote other products, according to author Alfred Chandler Jr.

“Specialties, such as Nujol, Flit, Mistol, and other petroleum by-products that could not be effectively sold through the department’s sales organization were combined in a separate subsidiary — Stanco,” noted Chandler in his book, Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise.

Dr. Seuss later said his experience working at Standard Oil helped him develop his fantastical characters and tales.

Chandler’s 1962 book also examined General Motors Company, Sears, Roebuck and Company, and gunpowder manufacturer E.I. du Pont de Nemours.

“Quick, Henry, the Flit!”

Geisel’s fortuitous bug-spray cartoon depicted a medieval knight in his bed, facing a dragon who had invaded his room, and lamenting, “Darn it all, another dragon. And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit.”

According to an anecdote in Judith and Neil Morgan’s 1995 book Dr. Seuss and Mrs. Geisel, the wife of the advertising executive who handled the Standard Oil account was impressed by the cartoon.

Creating characters for Standard Oil products helped Geisel become a successful children’s book author. Circa 1935 Flit ad courtesy University of California San Diego Library.

“At her urging, her husband hired the artist, thereby inaugurating a 17-year campaign of ads whose recurring plea, ‘Quick, Henry, the Flit!,’ became a common catchphrase,” noted a curator of the Dr. Seuss Collection at the University of California, San Diego.

“These ads, along with those for several other companies, supported the Geisels throughout the Great Depression and the nascent period of his writing career,” the curator added.

Besides promoting the Standard Oil companies Flit and Esso, Dr. Seuss’ creations helped sell such diverse goods as ball bearings, radio programs, beer brands, and sugar, notes the library, located in La Jolla, where Geisel was a longtime resident.

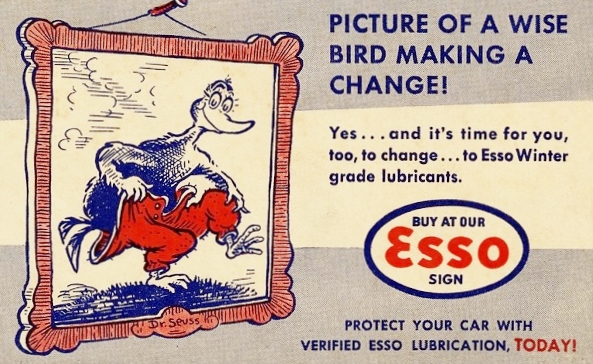

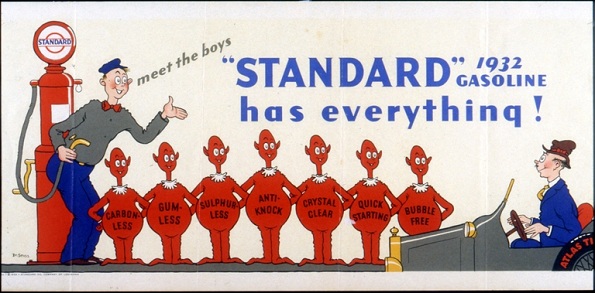

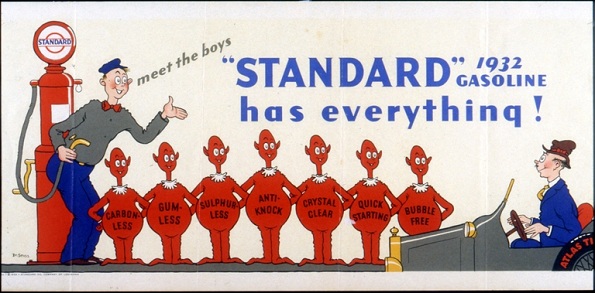

This 1932 Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) advertisement is among those preserved by the Dr. Seuss Collection of the Mandeville Special Collections Library at the University of California, San Diego.

At the University of California San Diego, the Dr. Seuss Collection in the Mandeville Special Collections Library contains original drawings, sketches, proofs, notebooks, manuscript drafts, books, audio and videotapes, photographs, and memorabilia.

More than 8,500 items document and preserve Dr. Seuss’ creative achievements, beginning in 1919 with his high school activities and ending with his death in 1991.

Karbo-nockus and Other Critters

The future Dr. Seuss added a host of zoological oddities to Standard Oil’s lexicon while promoting the product of Esso (the phonetic pronunciation of the initials S and O first used in 1926). His critters promoted Essomarine oil and greases as well as Essolube Five-Star Motor Oil.

Standard Oil Company advertising campaigns provided a steady income to Theodor Geisel and his wife throughout the Depression, and experiments with drawing styles.

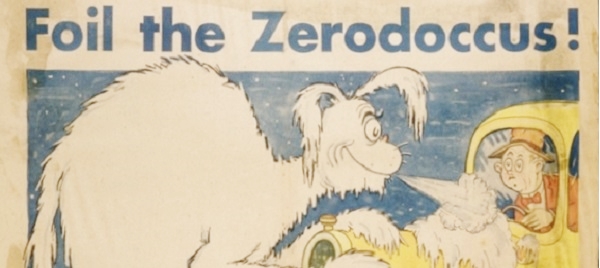

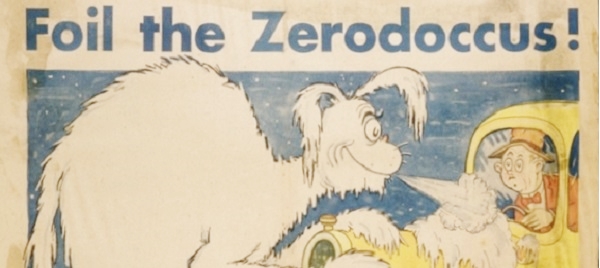

Smiling, toothy creatures such as Zero-doccus, Karbo-nockus, Moto-raspus and Oilio-Gobelus appeared in advertisements that warned motorists of the hazards of driving without the protection of Standard Oil lubrication.

Advertised in the 1930s with Dr. Seuss characters, Essolube motor oil continues to be sold internationally by the ExxonMobil.

“Meet the Zero-doccus. He is the first of a group of terrible beasts that are being turned loose in the advertising of Essolube, Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) products,” reported the December 8, 1932, Printers’ Insider, an advertising trade journal.

Other Esso “moto-monsters” would be introduced in newspapers and outdoor posters in coming months, the trade journal proclaimed.

“These creatures symbolize and dramatize some of the troubles of motorists who use inferior oils. The Zero-doccus pounces on cold motors and makes quick starting difficult with ordinary oils,” the article noted. “He and his coming friends are the creations of Dr. Seuss of ‘Quick, Henry, the Flit!’ fame.”

A dependable income from illustrating Standard Oil advertising during the Great Depression helped “Dr. Seuss” publish his first children’s book in 1936.

The Printers’ Insider article predicted the strange Esso creatures would prove popular when they appeared in ads nationwide.

The Seuss Navy

Throughout his early hard years, these Standard Oil advertising campaigns provided steady income to Geisel and his wife. “It wasn’t the greatest pay, but it covered my overhead so I could experiment with my drawings,” he later said.

Geisel noted his advertising work allowed him to experiment with creating subtle visual messages while using wacky rhymes in storytelling.

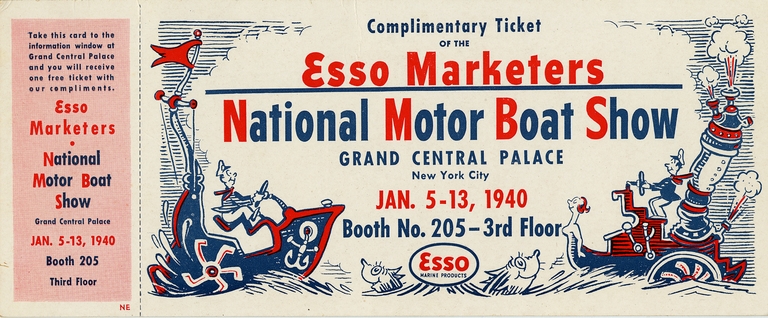

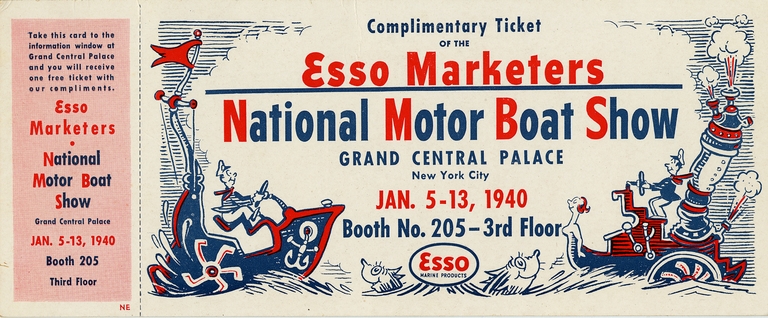

In 1936, Geisel designed Standard Oil’s Essomarine booth for the National Motorboat Show — and created the phenomenally successful “Seuss Navy.” Young and old visitors were commissioned as admirals and photographed with whimsical characters made of cardboard.

Standard Oil Company marketers promoted Essomarine products and the “Seuss Navy” during the January 1940 National Motor Boat Show in New York City.

By 1940, the Seuss Navy included more than 2,000 enthusiastic admirals (with such notables as bandleader Guy Lombardo). Geisel remembered that, “It was cheaper to give a party for a few thousand people, furnishing all the booze, than it was to advertise in full-page ads.”

As Dr. Seuss, Geisel wrote and illustrated his first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, published on December 21, 1937, by Vanguard Press after being rejected by 27 other publishers.

Twenty years later, The Cat in the Hat was inspired by a 1954 Life Magazine essay critical of children’s literacy and the stilted “See Spot Run” style of reading primers. Published in 1957, The Cat in the Hat used just 236 words — and only 14 of them with two syllables. It remains his most popular work.

The former Standard Oil advertising illustrator wrote more than 50 children’s books over a half-century career that brought the world Hop on Pop, Green Eggs and Ham, and many others. Children lost a friend on September 24, 1991, when Theodor Seuss Geisel died at the age of 87.

View online the Dr. Seuss Collection: Advertising Artwork of Dr. Seuss, preserved by Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California.

Kerosene in Art

At the beginning of the 20th century, French illustrator Jules Chéret (1836-1933) was famous for his lithograph posters for theaters, music halls, beverages, and medicines. During a long career, many of his commercial posters promoted a French petroleum company’s lamp oil.

Chéret, who would be called “the father of the modern lithograph” and “king of the poster,” produced popular posters for “Saxoleinem,” the company’s refined “pétole de sureté” — safety lamp oil.

French advertisement for “The Halo of the South,” a safety oil for lamps, in an 1895-1900 lithograph.

“He was often imitated, and an entire generation of artists would follow and build on his work. One of them was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec,” notes Chicago’s Richard H. Driehaus Museum. “To acknowledge his debt to the older artist, Lautrec sent Chéret a copy of every poster he produced.”

Learn about more examples of artists and the petroleum industry in Oil in Art.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss (2010); The History of the Standard Oil Company: All Volumes

(2010); The History of the Standard Oil Company: All Volumes  (2015); Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise (1962); Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography (1995). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2015); Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise (1962); Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography (1995). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Seuss I am, an Oilman.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/seuss-the-oilman. Last Updated: January 9, 2026. Original Published Date: December 1, 2008.