When Phillips Petroleum scientists invented a new plastic in the early 1950s, getting it from lab to market proved difficult. Enter Wham-O.

Research scientists in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1951 discovered how to make a durable, high-density polyethylene, and the marketing executives at their oil and natural gas company named it Marlex. But Phillips Petroleum sales reps searched in vain for buyers of the new plastic until the Wham-O toy company found it ideal for making hoops and flying platters.

Prompted by a post World War II boom in demand for plastics, Phillips Petroleum Company invested $50 million to bring its own miracle product — Marlex — to market in 1954. With a high melting point and tensile strength, the synthetic polymer would stand out from the company’s thousands of patents.

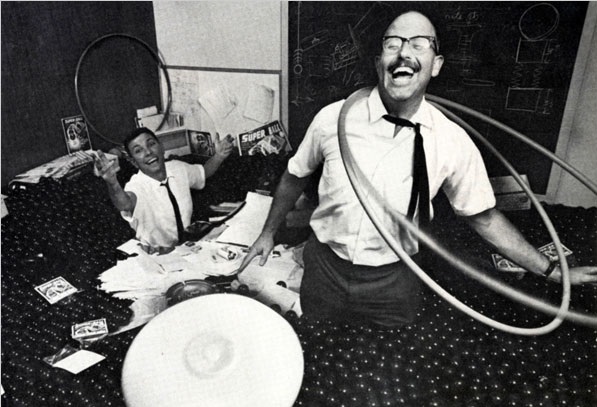

To make Hula Hoops and Frisbees, Arthur Melin, right, and his Wham-O Company partner Richard Kerr, left, chose Marlex — the world’s first high-density polyethylene plastic.

Phillips Petroleum gambled that its new plastic would be perfect for all manner of emerging products trying to keep up with consumer demand. With millions of dollars already committed, company executives and Wall Street investors expected immediate results from the unusual lab product.

Fun with Polyethylene

Marlex, a high-density polyethylene, was created by Phillips research chemists J. Paul Hogan and Robert L. Banks, who had been researching gasoline additives. In their experiments, Hogan and Banks studied catalysts.

At first, few companies knew what to do with Phillips Petroleum’s new plastic. Demand for “Marlex” would come from “the undisputed granddaddy of American fads.” This 1958 Associated Press photo shows Los Angeles children demonstrating their skills for “Art Linkletter’s House Party” show.

“In June 1951, they set up an experiment in which they modified their original catalyst (nickel oxide) to include small amounts of chromium oxide,” noted the American Chemical Society in 1999. Their work was expected to produce low-molecular-weight hydrocarbons.

“As Paul Hogan recalls it, he was standing outside the laboratory when Banks came out saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got something new coming in our kettle that we’ve never seen before.’ Running inside, they saw that the nickel oxide had produced the expected liquids. But the chromium had produced a white, solid material. Hogan and Banks were looking at a new polymer — crystalline polypropylene.”

A few years later when Phillips introduced high-density polyethylene in 1954, under the brand name Marlex, “company marketing executives were wildly optimistic, expecting that the product would be a big hit and that Phillips would not be able to keep it on the shelves.”

Unlike another synthetic material introduced decades earlier by DuPont (see Nylon, A Petroleum Polymer), the transition from laboratory to mass production proved far more difficult than anticipated.

When customers failed to materialize, the dingy, inconsistently sized, off–specification pellets accumulated. Phillips Petroleum found itself with no buyers and warehouses growing full of Marlex. The Bartlesville company searched for new customers.

Relief came from an unexpected source.

Petroleum Product Toy

The Wham-O Company was born in a California garage in 1948 when Richard Knerr and Arthur “Spuds” Melin began making 75-cent wooden slingshots using a jigsaw they purchased on an installment plan.

In August 2009 Titusville, Pennsylvania, celebrated the 150th anniversary of the first U.S. oil discovery. The parade included a float from Oil Creek Plastics. Nearby is the Drake Well Museum. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The company’s name came from its first product, the “Wham-O Slingshot,” and the sound made when a pebble hit a target. As its mail-order business grew, Wham-O in 1957 added a flying disc toy, the “Pluto Platter” — today’s Frisbee — to their product line. The next year, they introduced a simple Australian amusement, the “Hula-Hoop.”

“The great obsession of 1958 — the undisputed granddaddy of American fads…the hoop rewrote toy merchandising history,” noted Richard Johnson in his 1985 book American Fads. When the phenomenal hoop craze ignited, Wham-O needed plastic tubing. A lot of it.

The Wham-O company first used a W.R. Grace & Company product called Grex — a petroleum-based plastic produced in Pennsylvania. In Titusville, birthplace of the U.S. oil industry in 1859, the Skyline Plastics Company worked overtime extruding Grex into the plastic Hula-Hoops as the craze swirled across the nation.

Retired Titusville plant superintendent Robert Poux, 83, remembers 125 employees working three-shifts, seven days a week, just to keep up. Wham-O sold more than 25 million Hula-Hoops in the first four months (at $1.98 each). They sold more than 100 million in two years.

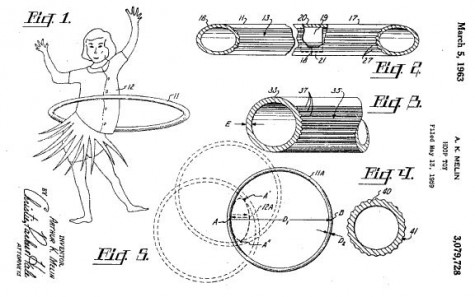

“Extruded tubing is desirable because it may be economically fabricated in continuous lengths,” Arthur Melin noted in his patent application describing a hoop weighing 10 ounces.

Wham-O’s nationwide daily production ultimately peaked at about 20,000 per day. There soon was not enough Grex and Phillips Petroleum’s once ignored miracle polypropylene, Marlex, was suddenly very much in demand. Hula-Hoop plastic-extruding plants sprang up in Chicago, Newark, and Toronto, Canada.

Resolving initial manufacturing problems after the completely unanticipated demand for Marlex, Phillips positioned itself as a prime source for durable plastics. New industrial, medical, and consumer product uses ensured Phillips Petroleum’s $50 million investment in polymer research would be rewarded many times over.

And as the Hula-Hoop fad diminished, Wham-O continued using tons of Marlex — for the production of Frisbees.

The Wham-O Frisbee

In 1948, a California newspaper reported, “Two local men, pooling resources after the words ‘flying saucers’ shocked the world a year ago, have invented a new, patented plastic toy shaped like the originally reported saucer.”

Walter Morrison and Warren Franscioni of San Louis Obispo formed Partners in Plastic (Pipco) and sold their “Flyin’ Saucers” for 25 cents each. By 1955, Morrison had gone on his own to sell his “Pluto Platters” — the basic design of today’s Frisbee — when Wham-O acquired the rights.

Wham-O began producing its own plastic Frisbees on January 13, 1957. Morrison would receive more than one million dollars in royalties for his flying platter invention.

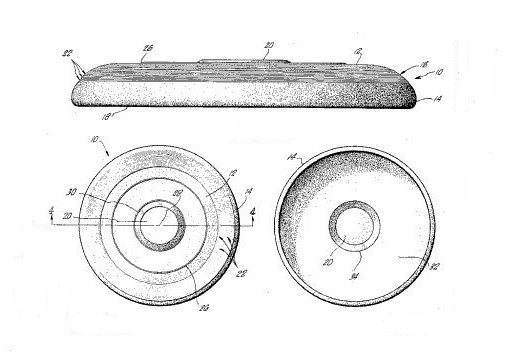

Wham-O began producing Frisbees in January 1957. A decade later, an improved “professional” Frisbee included the “Rings of Headrick” for added stability. Detail from U.S. Patent No. 3,359,678. Image courtesy the Disc Golf Association, Watsonville, California.

“Sales soared for the toy, due to Wham-O’s clever marketing of Frisbee playing as a new sport,” says Mary Bellis in her article, “First Flight of the Frisbee.” In 1967, New Jersey high school students invented Ultimate Frisbee, a cross between football, soccer and basketball.

According to Bellis, it was also 1967 that Wham-O’s Ed Headrick patented an improved design that became today’s Frisbee, with its band of raised ridges — called the Rings of Headrick — that stabilized flight “as opposed to the wobbly flight of its predecessor the Pluto Platter.”

According to the Disc Golf Association, Watsonville, California, Disc Golf began with “Steady” Ed Headrick, the father of disc golf and modern day disc sports.

Phillips chemist Paul Hogan is pictured in a Phillips Petroleum Company Museum display of products made of high-density polyethylene, a plastic he and fellow chemist Robert Banks invented. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Today, because young people often fail to realize plastics are made from petroleum, many community oil and gas museums include these iconic toys in “petroleum products” exhibits.

Heroes of Chemistry

Phillips Petroleum Company chemists Paul Hogan and Robert Banks invented a way to make solid polymers (U.S. Patent No. 2,825,721) — and launched the modern world of plastics.

According to the American Chemical Society, “The two researchers found the catalyst that would transform ethylene and propylene into solid polymers. The plastics that resulted — crystalline polypropylene and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) — are now the core of a multibillion-dollar, global industry.”

When Paul Hogan died at age 92 on February 19, 2012, he was described by those who knew him as “a modest man who did not care to dwell on his many scientific achievements and accolades, Hogan’s name is found on more than 50 patents,” according to the Bartlesville Examiner-Enterprise.

Fellow research chemist Robert Banks (1921-1989) shared in many of the Phillips Petroleum accomplishments relating to high-density plastics. Prior to joining the oil company in 1946, Banks had been a process engineer at an aviation gasoline plant during World War II.

In 1998, the American Chemical Society gave Banks (posthumously) and Hogan a “Heroes of Chemistry” award for the use of petrochemicals in the automotive industries. Their discovery of polypropylene and high-density polyethylene was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark in 1999.

Robert L. Banks and J. Paul Hogan were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Phillips, The First 66 Years (1983); American Fads

(1985); Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century

(1996); Enough for One Lifetime: Wallace Carothers, Inventor of Nylon (2005). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS supporter. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Petroleum Product Hoopla.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/petroleum-product-hoopla. Last Updated: January 16, 2025. Original Published Date: February 3, 2011.