America’s first unsuccessful well drilled for oil still achieved many petroleum industry “firsts.”

Modern oil and natural gas exploration and production technologies began with19th-century wells drilled in northwestern Pennsylvania. Just four days after America’s first commercial oil well, a second attempt nearby resulted in the first “dry hole” for the new U.S. petroleum industry.

Edwin L. Drake drilled the first U.S. oil well specifically seeking oil on August 27, 1859, at Titusville, Pennsylvania. His historic feat included inventing the method of driving a pipe downhole to protect the integrity of the wellbore. The former railroad conductor borrowed a kitchen water pump to produce the first barrel of oil.

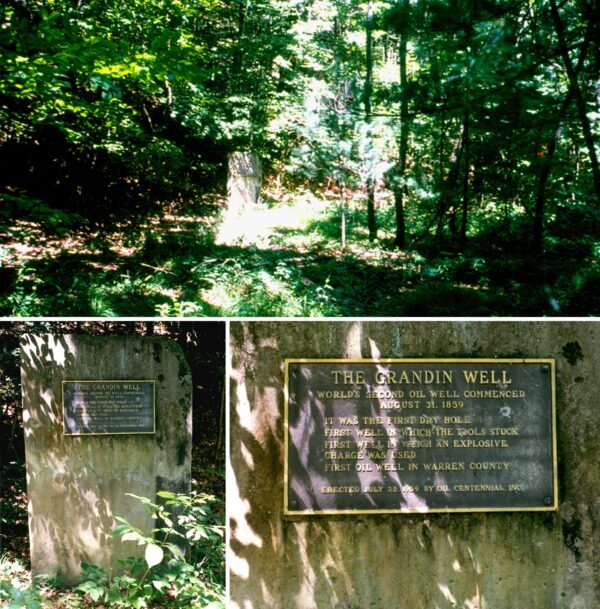

A historical marker near U.S. 62 at Tidioute, Pennsylvania, commemorates the site of America’s first “dry hole” with a 1959 centennial monument. Photos from a 1996 field trip, courtesy William R. Brice, PhD, Professor Emeritus of Geology & Planetary Science at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown.

Although Drake’s headline-making discovery at Oil Creek launched an industry, an August 31 well would achieve far lesser-known milestones. It was on that day that 22-year-old John Livingston Grandin began drilling America’s second well to be drilled for petroleum.

Two days after “Drake’s Folly” at Titusville produced commercial amounts of oil from a depth of 69.5 feet, the surprising news reached a general store in Tidioute, 20 miles away. With each barrel of oil reportedly selling for 75 cents, John L. Grandin, the owner’s son and an aspiring entrepreneur, saw an opportunity.

Growing demand for a cheap fuel for lamps led to early Pittsburgh refineries seeking oil for making kerosene (see also illuminating Gaslight). From his boyhood, Grandin knew of petroleum seeps to be found on Gordon Run on the Campbell Farm south of town. He bought 30 acres surrounding the oil spring at $10 per acre.

Today, visitors to the scenic Allegheny National Forest Region on U.S. 62 near Tidioute, Pennsylvania, will discover this Warren County roadside marker.

Within a day, Grandin hired blacksmith Henry H. Dennis, said to be the handiest man in the region, to “kick down” a well using the time-honored spring-pole method.

Drilling with this simple method used in ancient China, the Grandin well reached almost twice as deep as Drake’s steam-powered, cable-tool effort, which had the financial backing (and patience) of the Seneca Oil Company of Connecticut’s George Bissell and company investors.

The Drake well had used the latest drilling technology for making hole — a cable-tool rig powered by a steam boiler and with a six-horsepower horizontal steam engine.

Exploring Drilling Technologies

For their well, Grandin and Dennis constructed a rough 20-foot derrick above a spring pole. Using a discarded tram axle, Dennis made a surprisingly workable reamer. Drilling with the axle as a chisel worked well, deepening the borehole — until the chisel became stuck at 134 feet, “where it never saw daylight again!” as described in a contemporary account.

All attempts to retrieve the axle drill bit failed, and the drilling tool was lost down-hole for the first time. This “stuck tool” milestone remains a small but important footnote in the oil and natural gas industry’s technology history.

Even as percussion drilling evolved into steam-powered, cable-tool derricks like the one used by Drake, heavy assemblies would get jammed in the borehole and could no longer be repeatedly lifted and dropped (learn more in Fishing Petroleum Wells).

However, all was not lost at Grandin’s spring-poled well, at least as far as blacksmith Dennis was concerned.

An early technology for drilling brine wells – the “spring pole” – was replaced by steam-powered cable tools. Photo from “The World Struggle for Oil,” a 1924 film by the Department of the Interior.

Dennis put together several makeshift canisters charged with blasting powder and experimented with timing fuses in hopes of breaking things loose downhole. “The explosion was sensibly felt upon the surface,” noted a report of his third attempt. “Mr. Dennis says, the ground trembled like an earthquake under his feet!”

With this noteworthy effort, the Grandin well was ruined in the first recorded shooting to improve oil production of a well, and its first failure. The U.S. petroleum industry had its first dry hole.

Firsts of the Second U.S. Well

Despite not finding the oil-producing formation (the Venango Sands), the Grandin well produced lessons for the young U.S. exploration and production industry.

Petroleum industry milestones of Grandin’s drilling of the second U.S. well seeking oil included:

♦ First dry hole

♦ First well in which tools stuck

♦ First well “shot” with an explosive charge

In addition to his father’s store in the Pennsylvania oil region, the Grandin family found wealth in the lumber industry as demand for wooden derricks skyrocketed in Warren County as more wells were drilled.

Oil fever continued in the new U.S. industry (see Boom Town at Pithole Creek), and most drilling attempts ended like the Grandin well. Then the new sciences of petroleum geology and petroleum reservoir engineering radically improved exploration and production methods.

Drilling advances using rotating “fishtail” bits (used in the headline-making 1901 gusher at Spindletop Hill) began allowing exploration through hard rock formations miles beneath the surface. Production technologies would also improve.

A 15-inch bronze sculpture by Lincoln H. Fox, “Dressing the Bit,” was presented to President Ford at the 1975 dedication of the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum in Midland, Texas. Photo courtesy Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum.

Even with advances in seismic surveys, geology and petroleum engineering, more than one-third of modern exploration wells drilled — costing millions of dollars each — end up as dry holes. Of the 2,803 exploratory wells drilled in 2009, natural gas was discovered by 1,188 and oil found by 626 wells. There were 989 dry holes.

Grandin became successful in the oilfield service industry — long before the oilfield technology pioneers Erle Halliburton, R.C. “Carl” Baker, and many others.

Grandin Wellsite Marker

“Firsts” get the jubilees, centennials and sesquicentennials. “Seconds” are lucky to get roadside markers, and even those can be very hard to find. In 1959, during the centennial of Drake’s discovery, Grandin’s well was not neglected.

In 1959, a privately funded stone monument was erected at the Warren County well site with this inscription:

THE GRANDIN WELL — World’s second oil well, commenced August 31st, 1859. It was the First Dry Hole, First Well in Which Tools Stuck; First Well in Which an Explosive Charge Was Used; First Well in Warren County, PA. Erected July 22, 1959, by Oil Centennial Inc.

A Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission roadside marker can also be found on U.S. 62, four-tenths of a mile south of the Allegheny River Bridge at Tidioute in Warren County. The first U.S. oil well’s sesquicentennial in 2009 was commemorated for a week in the “Valley that Changed the World.”

In Titusville, the Drake Well Museum draws thousands of visitors to exhibits that celebrate the 1859 well that did discover oil. A new industry began to explore for the new resource for refining into lamp fuel, and by the 20th century, gasoline.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language (2012); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “First Dry Hole.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/first-dry-hole. Last Updated: July 18, 2025. Original Published Date: December 1, 2005.