Letters, brochures, and tip sheets promoted Dr. Frederick Cook’s dubious petroleum ventures.

He was a controversial North Pole visitor whose fraudulent claims were part of failed oil company ventures, a mail fraud conviction, and jail time.

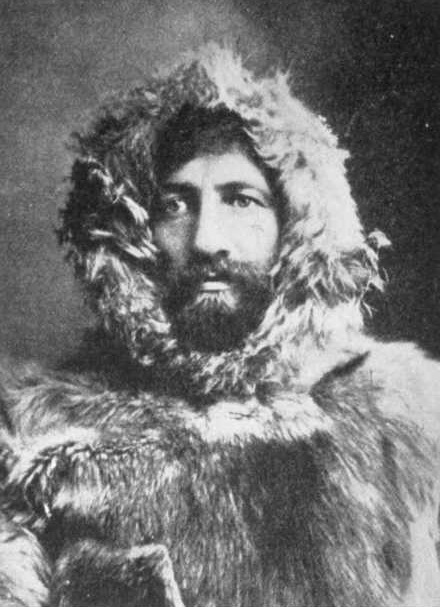

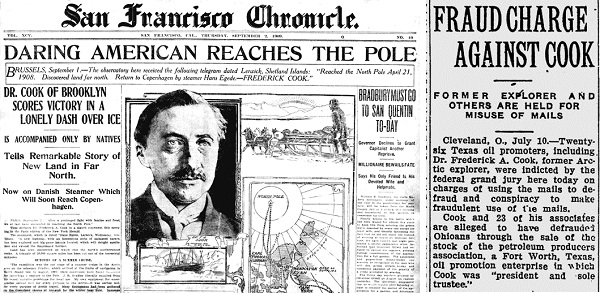

Arctic explorer Dr. Frederick Albert Cook in 1908 made the widely accepted claim to have reached the North Pole after an arduous journey. He became a celebrity after accounts of his feat appeared in newspapers. Cook’s near approach to the pole would be erased in less than a year when Admiral Robert E. Peary made a scientifically documented journey to achieve the milestone.

In 1909, a special commission at the University of Copenhagen investigated Cook’s conclusion that he had reached the pole before Peary. After examining Cook’s records, the commission on December 21, 1909, found no evidence Cook had reached the pole. The U.S. Congress formally recognized Peary’s claim in 1911.

“Dr. Frederick A. Cook, the Brooklyn physician whose reported discovery of the North Pole has thrilled the civilized world.”

Cook would spend years defending his claim, despite the lack of navigation evidence. He published My Attainment of the Pole and threatened to sue anyone who said he had faked the trip. Then he got into the petroleum exploration business.

Celebrity Promoter

In 1917 Cook conducted geological explorations in Wyoming for his newly formed company, the Texas Eagle Oil Company of Fort Worth. Wyoming’s first real petroleum boom had arrived in 1908 when Salt Creek’s “Big Dutch” well came in as a gusher, bringing a flood of entrepreneurs and investors (see First Wyoming Oil Wells).

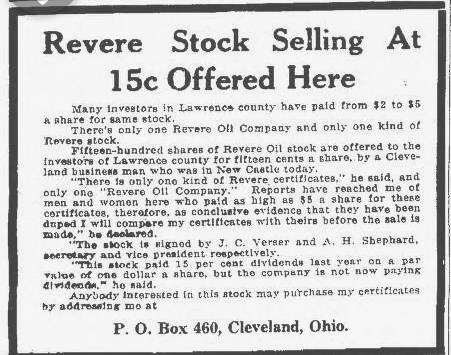

However, even with railroad tank cars, the lack of Wyoming infrastructure meant it could not compete in eastern markets because of transportation costs. Falling oil prices forced the Texas Eagle Oil Company into bankruptcy. Undismayed, Cook rebounded in September 1920 with a group of Fort Worth investors and incorporated the Revere Oil Company.

His Texas Eagle experience had convinced him to focus on fundraising from stockholders of small, failing companies. “If I could have raised $50,000, I could have saved that large company with its large properties for its stockholders,” Cook later claimed.

“Combining with the Revere taught me that that was a reasonable method of how many other companies then being neglected or lying inactive, put under one head, could be renovated and the stockholders put in a position to make some money,” Cook added. U.S. Postal Service investigators saw it differently.

The famed but fraudulent explorer who had laid claim to reaching the North Pole in 1908 was convicted in 1923 after testimony from almost 300 witnesses.

Subsequent federal grand jury indictments of Cook declared that “In March 1921, the promoters, it is charged, entered upon a ‘so-called merger plan,’ each merger resulting in the acquisition of additional lists of stockholders who were advised in extravagantly phrased circulars and letters of the merger and promised safety from loss in their investment in the old company.”

The indictments noted that investors were required to “exchange their stock dollar for dollar for stock in the Revere Company with the stipulation that they purchase new stock equal to 25 percent of their holding in the ‘merged company.’”

Blizzard of Hyperbole

Undeterred by legal threats, Cook organized another venture in 1922 — the Petroleum Producers’ Association — using the same Revere Company “fold in” merger scheme as it was known at the time.

“Cook’s response was to raise the level of hyperbole in his promotional literature,” reported Roger and Diana Olien in a Business and Economic History article. “His own prose tended to be unexciting, so he hired one of the best ‘pens’ in the business, Seymour E.J. “Alphabet” Cox, to write high-powered material at a weekly salary of $5,000 plus commissions on some stock sales.”

Revere Oil Company and the Petroleum Producers’ Association acquired lists of vulnerable stockholders from failed, smaller companies, “most of which investors had already suffered huge losses.”

Cook and skilled adman Cox launched a blizzard of hyperbole. Their marketing campaign eventually amounted to a daily total of up to 30,000 promotional letters, brochures, and industry “tip sheets.” Instead of petroleum geologists and drilling contractors, Cook hired more than 50 full-time stenographers, including two “addressograph” operators, two printers, and a full-time mail boy.

“Cox’s genius as a copywriter soon was obvious. The collaboration of Cook and Cox brought in $250,000 in less than two months — as much as Cook alone had raised in nearly a year,” noted the Oliens in their 1988 article, “Competition for Capital in Two Oil Ventures.”

The Arctic explorer’s fraudulent marketing convinced thousands of unwary investors to buy into the Petroleum Producers’ Association. The fraudulent association along with the Revere Oil Company would later be charged for “having taken over more than 250 smaller companies, in most of which investors had already suffered huge losses.”

Among the companies taken over was the Rose City Petroleum Company, which was $50,000 in debt at the time, according to G.W. Hays, former governor of Arkansas — and a shareholder in the company. Established in 1921 to build a 1,000-barrel-a-day refinery in Little Rock, Rose City Petroleum had struggled, making its investors susceptible to Cook’s scheme.

Hundreds of thousands of promotional letters, brochures, and industry “tip sheets” promoted the failed explorer’s oil venture, which earned him a Leavenworth, Kansas, prison sentence.

Newspapers reported that Cook bought “sucker lists” from defunct and dying oil companies to target vulnerable investors, “each one holding out a new hope of recouping money lost in a previous adventure or of becoming rich overnight from the black gold that flows from Texas oil wells.”

Federal investigators charged that in three years of operations, Revere Oil Company bilked investors of more than $6 million.

In 1923, after testimony from almost 300 witnesses, Cook, “Alphabet” Cox and others were convicted of ”dispersing stock-sales revenues as dividends, claiming income from nonproducing wells, and otherwise misrepresenting the company’s position.”

Learn more about “Alphabet” Cox in Prudential Oil and Refining Company.

Frederick Albert Cook, the self-proclaimed conqueror of the North Pole, was fined $12,000 and sentenced to 14 years and 9 months in Leavenworth prison in Kansas. “You have at last got to the point where you can’t bunko anybody,” said District Court Judge John Killits.

Paroled in 1930, Cook received a pardon from President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940. The explorer who almost reached the North Pole died five months later at age 75. Smithsonian magazine examined Cook’s claim in an April 2009 article, “Who Discovered the North Pole?”

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? Exaggerated and sometimes fraudulent claims by shady ventures seeking investors grew in the years following World War I — especially as giant oilfield discoveries made headlines (see Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever).

As the Great Depression approached, states began passing “blue sky laws” to regulate securities sales and protect the public. Congress finally acted in 1934 to stop skilled business hucksters like “Alphabet” Cox from taking advantage of unwary investors seeking often fictional profits.

_______________________

Recommended Reading – My Attainment of the Pole (1911); Easy Money: Oil Promoters and Investors in the Jazz Age (1990). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/secret-offshore-history-of-the-glomar-explorer. Last Updated: December 9, 2025. Original Published Date: April 1, 2013.