The Elizabeth Watts shipped hundreds of barrels of petroleum from Philadelphia to London during the Civil War.

The 19th century U.S. petroleum industry launched many new industries for producing, refining, and transporting the highly sought after resource. With oil demand rapidly growing worldwide, America exported oil (and kerosene) during the Civil War when a small Union brig sailed across the Atlantic.

Soon after Edwin L. Drake drilled the first American oil well in 1859 along a creek in northwestern Pennsylvania, entrepreneurs swept in and wooden derricks sprang up in Venango and Crawford counties.

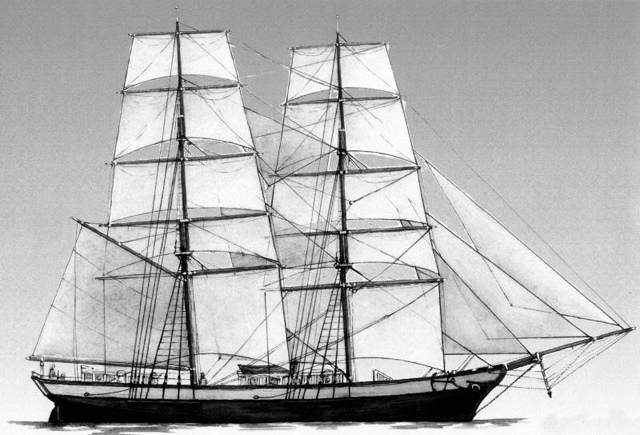

Launched in 1847 by the shipbuilding firm of J. & C.C. Morton of Thomaston, Maine, the Elizabeth Watts was about 96 feet long with a draft of 11 feet. The 224-ton brig made petroleum history during the Civil War.

As demand for oil-refined kerosene for lamps grew, oilfield discoveries created early boom towns like one at Pithole. Moving the resource from oilfields also brought the beginning of the petroleum industry’s transportation infrastructure.

“Doubt and distrust that preceded Drake’s successful venture suddenly fled before the common conviction that an oil well was the ‘open sesame’ to wealth,” reported Harpers New Monthly Magazine. After his historic discovery near Titusville, Drake bought up all the 40-gallon whiskey barrels he could find to transport his oil on barges down the Allegheny River to Pittsburgh refineries.

In January 1860, oil sold for $20 a barrel and brought jubilant investors huge profits, including Drake’s investors at the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut. By May 1861, more than 130 producing wells were crammed into the area, yielding 1,288 barrels of oil a day.

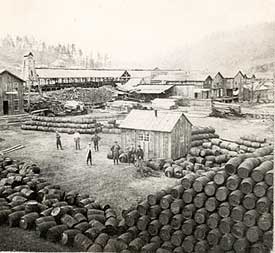

New cooperages joined the oil boom and stripped the Pennsylvania hillside forests to sell barrels at up to $3.25 each while teamsters charged up to $4 each to haul them. But with an oversupply of oil came plummeting prices and instability that would bring ruin to many fledgling petroleum companies.

About this time, the veteran cargo brig Elizabeth Watts was chartered by the successful Philadelphia import-export firm of Peter Wright & Sons. “She was a two masted, square-rigged ship well suited for the Atlantic cargo trade of the day,” noted J. & C.C. Morton, the Maine shipbuilding firm that constructed the 224-ton brig in 1847.

Since its founding in 1818, Peter Wright & Sons had grown and prospered, transporting glass and Queensware China among other commodities.

Barrels of vinegar – “Vinegar Bitters” – at New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1870 would be similar to the 1861 loading of oil and kerosene barrels aboard the Elizabeth Watts prior to departing the Port of Philadelphia for England. Photo courtesy New Bedford Whaling Museum.

At the prompting of new partner Clement Acton Griscom, the firm secured the Elizabeth Watts and Captain Charles Bryant for the novel purpose of transporting crude oil from Philadelphia to London. The three British consignees awaiting the cargo were G. Crowshaw & Company, Coates & Company, and Herzog & Company.

To reach Philadelphia docks, the oil would have to travel overland across Pennsylvania. The nearest railroad to Oil Creek’s prolific fields was a grueling trek on muddy roads clogged with teamsters’ wagons. The preferred rail head, owing to primitive road conditions, was the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad station at Miles Mills (now Union City), 20 miles north of Titusville.

42-Gallon Barrel

From Miles Mills, railroad flatcars laboriously stacked with barrels and pulled by a steam locomotive could make their way eastward to Philadelphia.

The 42-gallon barrel standard was officially adopted by members of the Petroleum Producers Association in 1872.

Despite the hazards and difficulty, 901 barrels of Pennsylvania crude and 428 barrels of refined kerosene made the trip. Each 40-gallon barrel weighed over 60 pounds empty and 348 pounds full of oil. The oil region’s producers had adopted a standard 42-gallon oil barrel as early as 1866, and the Petroleum Producers Association made it official in 1872 (see History of the 42-Gallon Oil Barrel).

At the Port of Philadelphia it took dockside stevedores 10 days to load the oily cargo aboard the moored Elizabeth Watts. Sailors were not anxious to sign on with a ship that could explode and burn even before casting off and sailing down the Delaware River toward the open sea. Capt. Bryant reportedly had to “shanghai” his crew of seven.

The cargo’s fumes were noxious, lurking, and explosive. No ship had ever crossed the Atlantic bearing such cargo. Whether by persuasion or chicanery, Capt. Bryant secured his crew, and the Elizabeth Watts departed the Philadelphia docks on November 19, 1861.

Saltwater residue would eat at the barrels’ glue and cause leakage. The risk of fire or explosion would be constant.

Forty-five days later, on January 9, 1862, the Elizabeth Watts sailed down the Thames River to arrive at London’s Victoria Dock. It took twelve days to unload the 1,329 barrels. Just one year later, Philadelphia would export 239,000 barrels of oil – still without the technology of railroad tank cars or “tanker” ships designed for the purpose (also see petroleum transportation).

Maritime historian and author William H. Flayhart has extensively researched the Port of Philadelphia and its contributions to the growth of the U.S. petroleum industry. In 2003, he also published Perils of the Atlantic Steamship Disasters, 1850 to the Present.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); Perils of the Atlantic: Steamship DIsasters, 1850 to the Present (2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “America exports Oil.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/america-exports-oil. Last Updated: November 8, 2023. Original Published Date: December 1, 2005.