by Bruce Wells | May 27, 2025 | Petroleum Products

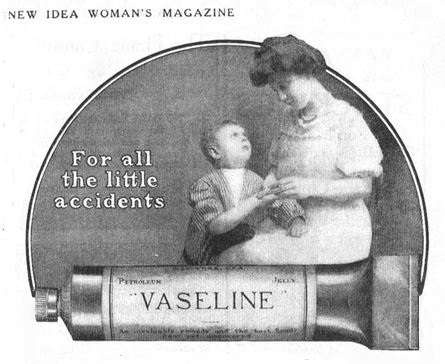

How oilfield paraffin created Vaseline and Maybelline cosmetics.

Few associate 1860s oil wells with women’s eyes, but they are fashionably related. From paraffin to Vaseline, this is the story of how the goop that accumulated around the sucker rods of America’s earliest oil wells made its way to eyelashes.

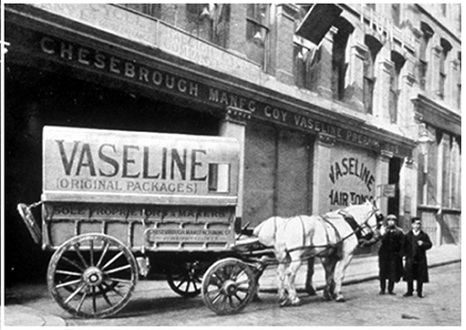

In 1865, a 22-year-old Robert Chesebrough left the prolific oilfields of Pithole and Titusville, Pennsylvania, to return to his Brooklyn, New York, laboratory. He carried samples of a waxy substance that clogged wellheads. He already had dabbled in the “coal oil” business with experiments on refinery processes.

Robert Chesebrough will find a way to purify the waxy paraffin-like substance that clogged oil wells in early Pennsylvania petroleum fields. Photo courtesy Unilever Corp.

Chesebrough’s laboratory expertise included distilling cannel coal into kerosene (coal oil), a lamp fuel in high demand among consumers. He also knew of the process for refining crude oil into a better kerosene.

Thus, when Edwin L. Drake completed the first U.S. oil well in August 1859, Chesebrough was among those who rushed to Pennsylvania oilfields to make his fortune.

“Now commenced a scene of excitement beyond description,” reported Scientific American. “The Drake well was immediately thronged with visitors arriving from the surrounding country, and within two or three weeks thousands began to pour in from the neighboring States.”

Chesebrough was convinced he too could get rich from the “black gold” of Pennsylvania’s oilfields.

Oilfield Sucker Rod Wax

Amid the Venango County exploration and production chaos, the young chemist noted a waxy buildup often confounded drilling. This paraffin-like substance clogged the wellhead and drew curses from riggers who had to stop drilling to scrape it away.

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96. This early bottle is from the collection of the Drake Well Museum in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

The only virtue of this goopy oilfield “sucker rod wax” was as an immediately available first aid for the abrasions, burns, and other wounds routinely afflicting the crews.

Paraffin to Vaseline

Chesebrough abandoned his notion of drilling a gusher and returned to New York, where he worked in his laboratory to purify the troublesome sucker-rod wax, which he dubbed “petroleum jelly,” one of America’s earliest petroleum products.

By August 1865, Chesebrough had filed the first of several patents “for purifying petroleum or coal oils by filtration.”

The chemist experimented with the analgesic effects of his extract by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying the purified petroleum jelly. He also gave it to Brooklyn construction workers to treat their minor scratches and abrasions.

After refining oilfield wax, Chesebrough experimented by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying his petroleum balm.

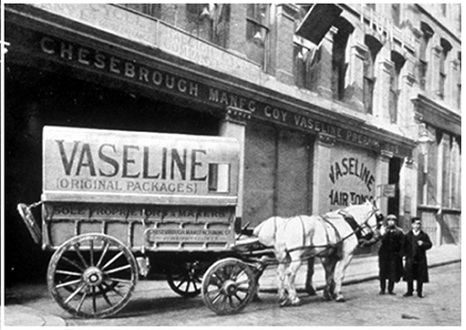

On June 4, 1872, Chesebrough patented a new product – “Vaseline.” His paraffin to Vaseline patent extolled the balm’s virtues as a leather treatment, lubricator, pomade, and balm for chapped hands. Chesebrough soon had a dozen wagons distributing the product around New York.

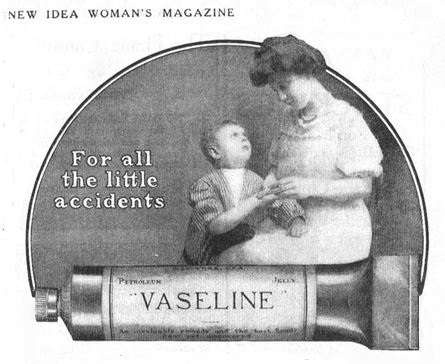

Customers used the “wonder jelly” creatively: treating cuts and bruises, removing stains from furniture, polishing wood surfaces, restoring leather, and preventing rust. Within 10 years, Americans were buying it at the rate of a jar a minute

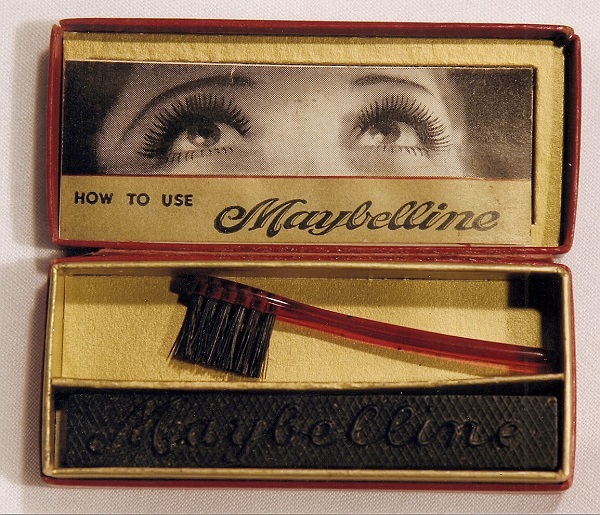

Women had once used toothpicks to mix lamp black with Vaseline. By 1917, Tom Williams was selling premixed “Lash-Brow-Ine” by mail order. Photo courtesy Sharrie Williams.

An 1886 issue of Manufacture and Builder even reported, “French bakers are making large use of vaseline in cake and other pastry. Its advantage over lard or butter lies in the fact that, however stale the pastry may be, it will not become rancid.”

Flavor notwithstanding, Chesebrough himself consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day. He lived to be 96 years old. It was not long before thrifty young ladies found another use for Vaseline.

Mabel’s Eyelashes

As early as 1834, the popular book Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion suggested alternatives to the practice of darkening eyelashes with elderberry juice or a mixture of frankincense, resin, and mastic.

“By holding a saucer over the flame of a lamp or candle, enough ‘lamp black’ can be collected for applying to the lashes with a camel-hair brush,” the book advised.

Chesebrough’s female customers found that mixing lamp black with Vaseline using a toothpick made an impromptu mascara. Some sources claim that Miss Mabel Williams in 1913 employed just such a concoction preparing for a date. Williams was dating Chet Hewes.

Women were using Vaseline to make mascara by 1915. Cosmetic industry giant Maybelline traces its roots to the petroleum product. “What a Difference Maybelline Does Make” magazine ad from 1937.

Perhaps using coal dust or some other readily available darkening agent, she applied the mixture to her eyelashes for a date. Her brother, Thomas Lyle Williams, was intrigued by her method and decided to add Vaseline in the mixture, noted a Maybelline company historian.

Lash-Brow-Ine

A more reliable version of the story — told by Williams’ grandniece Sharrie Williams — has Mabel demonstrating “a secret of the harem” for her brother.

“In 1915, when a kitchen stove fire singed his sister Mabel’s lashes and brows, Tom Lyle Williams watched in fascination as she performed what she called ‘a secret of the harem’ mixing petroleum jelly with coal dust and ash from a burnt cork and applying it to her lashes and brows,” Sharrie Williams explained in her 2007 book, The Maybelline Story and the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It.

“Mabel’s simple beauty trick ignited Tom’s imagination and he started what would become a billion-dollar business,” concluded Williams.

Silent screen stars like Theda Bara, right, helped glamorize Maybelline mascara. By the 1930s, the paraffin to Vaseline to mascara concoction was available at five-and-dime stores for 10 cents a cake.

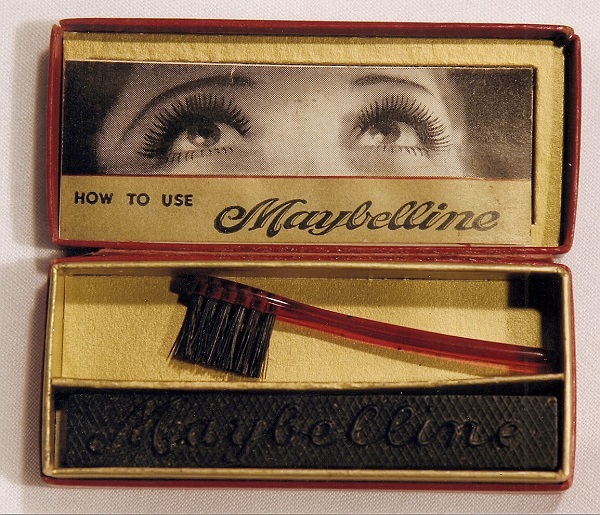

Inspired by his sister’s example, he began selling the mixture by catalog, calling it “Lash-Brow-Ine” (an apparent concession to the mascara’s Vaseline content). Women loved it.

When it became clear that Lash-Brow-Ine had potential, Williams, doing business in Chicago as Maybell Laboratories, on April 24, 1917, trademarked the name as a “preparation for stimulating the growth of eyebrows and eyelashes.”

Mail-Order Mascara

With sales exceeding $100,000 by 1920, Williams decided to rename the mascara Maybelline in honor of his sister, who worked with him in the Chicago office. Maybell Laboratories was renamed Maybelline in 1923 and concentrated on eye makeup. Mabel married Chet Hewes in 1926.

An unlikely petroleum product for women’s eyes.

Whatever its petroleum product beginnings, Hollywood helped expand the Williams family cosmetics empire. The 1920s silent screen had brought new definitions to glamour. Theda Bara – an anagram for “Arab Death” – and Pola Negri, each with daring eye makeup, smoldered in packed theaters across the country.

Maybelline trumpeted its mail-order mascara in movie and confession magazines as well as Sunday newspaper supplements. Sales continued to climb. By the 1930s, Maybelline mascara was available at the local five-and-dime store for 10 cents a cake.

Both Vaseline, now part of Unilever, and Maybelline, later a subsidiary of L’Oréal, have continued as highly successful products, distantly removed from northwestern Pennsylvania’s “Wonder Jelly” introduced in 1870.

Special thanks to Linda Hughes, granddaughter of Mabel and Chet Hewes, who reviewed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s paraffin to Vaseline to Mascara article. She asked AOGHS to note that Mabel was very dedicated to her brother’s work –- and helped run the Maybelline company in Chicago.

Crayola Crayons

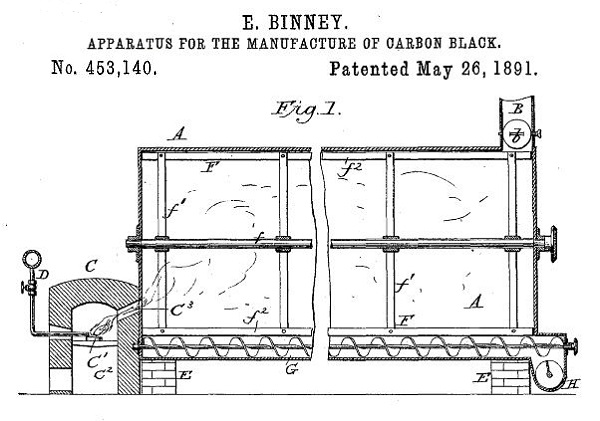

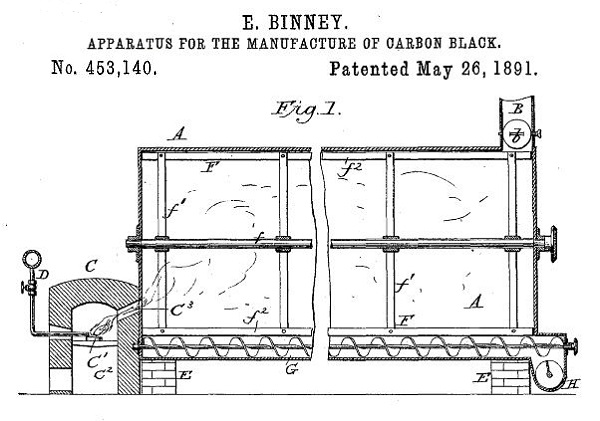

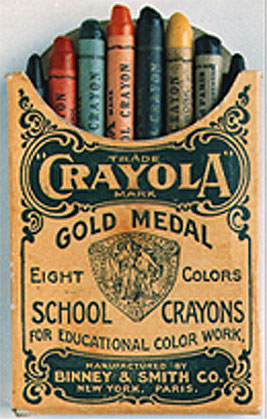

Paraffin from early U.S. oilfields also proved key to the phenomenal success of business partners Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith, who in 1891 patented an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.”

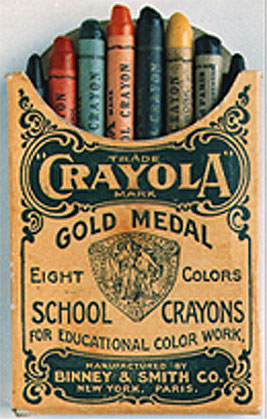

Soon, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed carbon black with oilfield paraffin to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker able to “stay on all” and named “Staonal,” still sold today. The company also manufactured a popular “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and a red, iron oxide barn paint.

By 1903, the Binney & Smith Company added color to paraffin for a new product, “Crayola” crayons. Learn more about their petroleum products in Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons. Oilfield paraffin also found its way into novelty candies like “wax lips.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/vaseline-maybelline-history. Last Updated: June 1, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2005.

by Bruce Wells | May 20, 2025 | Petroleum Products

Crayola — a 1903 petroleum product name combining the French words craie, chalk, and oléagineux, containing oil.

Many petroleum products hide in plain sight. For Pennsylvania’s Benny & Smith Company, common oilfield paraffin changed the company’s future by coloring children’s imaginations. Before inventing Crayola crayons, the partners patented a “dustless chalk,” a red oxide paint, and Staonal — “stay-on-all” — the blackest of black markers.

Three decades after America’s first oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons began with an 1881 refining patent by Edwin Binney to make carbon black, an intensely black pigment. Binney and partner C. Harold Smith had launched their company in Easton to sell inks, black polishes, and chalk for schoolroom blackboards.

Binney & Smith Company received an 1891 patent for an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black,” which produced a fine, soot-like black pigment — far better than any other in use.

Pennsylvania’s booming oilfields would prove key to success, beginning with using natural gas in a patented “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.” Binney & Smith Company later would add oilfield paraffin — the bane of oil producers since it clogged wells — and mix in colors to create a petroleum product named Crayola.

Manufacturing Carbon Black

On May 28, 1891, Binney received a patent for the company’s method to efficiently produce a fine, soot-like substance more intensely black than any other pigment in use at the time.

“The objects of my invention are to manufacture lamp-black from oil in an improved and economical manner, whereby waste of the product and unnecessary expenditure of labor are avoided,” Binney noted in his patent application.

His patent (No. 453,140) proclaimed a process to “manufacture carbon-black from gas in such a manner as to obtain improved quality of black which shall have the soft flaky texture of lamp-black made in ordinary ways.”

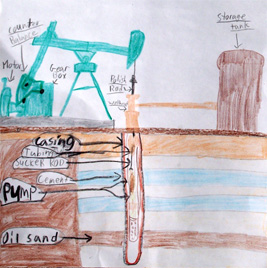

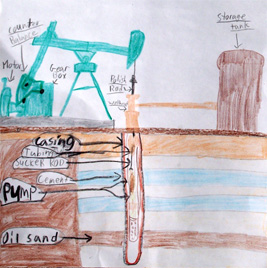

A fifth-grader’s skillful use of crayons illustrates oil production. Image courtesy Pioneer Oil Museum of New York, Bolivar.

The young U.S. petroleum industry, rapidly expanding its refineries to fuel kerosene for lamps, supplied Binney & Smith with oil and natural gas feedstock for the company’s carbon black. Revolving metal drums cooled the heat and smoke directed from the burning gas.

“Stay on All”

The company’s refining process produced a fine, soot-like substance of incredible blackness — a better pigment than any other. Binney & Smith’s carbon black received an award at the 1900 Paris Exposition, a world’s fair of the century’s achievements.

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed their carbon black product with oilfield paraffin and other waxes to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker for crates and barrels. The company promoted the marker as being able to “stay on all” and accordingly named “Staonal.”

Resulting from an 1891 carbon black patent, Binney & Smith added oilfield paraffin to produce a black marker. Staonal is still sold.

Staonal became a highly successful company product, but the concentrated carbon black content precluded its use by children. The company earlier had found great success manufacturing “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and red iron oxide for a red paint for barns.

Classroom Chalk

Although they longed for color, students in Alice Stead Binney’s classroom had to settle for dustless chalk. In fact, An-Du-Septic dustless chalk proved so popular among turn-of-the-century teachers that it won a Gold Medal at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Teachers like Alice loved the tidy new product, but their choices were limited. Pencils of the day were primitive, with square “leads” made from a variety of clays, slates, and graphite. Color writing implements were the toxic and expensive imports of artists, best kept away from schoolchildren.

Experiments in 1902 produced An-Du-Septic, a white dustless chalk soon popular with teachers. Photo courtesy Benny and Smith Company.

Alice’s husband Edwin, and his cousin, C. Harold Smith, created An-Du-Septic chalk as a consequence of expanding their pigment business into the sideline production of slate pencils for schools.

In Easton, the Binney & Smith Company, formerly the Peekskill Chemical Works, made its reputation by producing a red iron oxide for paint and carbon black for paints, inks, and iron stoves. Binney & Smith also produced shoe polishes. School teachers and their students would bring change.

Slate pencils and the very successful An-Du-Septic dustless chalk put Binney & Smith salesmen into America’s classrooms. The company’s sales force listened to teachers and learned there would be a ready market for inexpensive, non-toxic, brightly colored crayons.

“Crayola” from Oilfield Paraffin

In 1903, Binney & Smith launched a colorful product that would forever change childhoods. Alice Binney provided the name by combining the French word for chalk, craie, with the Old French word oléagineux — meaning something that contains oil.

The manufacturing process began with mixing small batches of carefully measured and hand-mixed pigments, paraffin, talc and other waxes. Employees individually rolled paper labels and pasted them onto each crayon by hand.

Identically packed into small boxes, thousands easily could be shipped in wooden crates. Sixteen Crayola crayons sold for 10 cents; eight for 5 cents: red, yellow, orange, green, blue, violet, black, and brown. Crayola became an instant hit.

Binney and Smith produced the first box of eight Crayola crayons in 1903 — red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown, and black.

The company’s proprietary formulas have remained a closely guarded secret as demand for its crayons has grown worldwide. Production capacity reportedly is more than four million crayons every day, thanks to oilfield paraffin from distant petroleum refineries delivered to Crayola’s Easton factory in railroad tank cars.

In January 2007, Binney & Smith became Crayola LLC in recognition of the company’s number one brand. The company is now known as Crayola. Crayola has grown to become a $500 million a year business — a successful union of the petroleum industry to the colorful world of children’s imaginations.

“This organizational and name change showcases the company’s Crayola brand, sold by Binney & Smith since 1903,” explained the company, which also opened a museum in Easton. Crayola is sold in more than 80 countries, “and represents innovation, fun, kids and quality.”

As paraffin continued to find its way into products (see The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes), manufacturers in 1912 for the first time added Binney & Smith’s carbon black to tires. Until the addition of carbon black to improve durability, auto tires were white.

Carbon Black Hits the Road

In 1839, bankrupt Philadelphia hardware merchant and erstwhile inventor Charles Goodyear accidentally dropped rubber and sulfur on a hot stovetop. The rubber charred like leather yet remained elastic, a discovery that led to “vulcanization.”

During the new process, natural rubber could be transformed into an industrial product with innumerable uses. Goodyear’s famous lawyer, Daniel Webster, praised his client’s invention. “It introduces quite a new material into the manufacture of the arts, that material being nothing less than elastic metal,” Webster proclaimed.

Automobile tires were the ideal application for this new product. Between 1895 and 1905, more than 77,000 new automobiles were registered in the United States (See Cantankerous Combustion — First U.S. Auto Show).

The tires of this 1904 Oldsmobile Model N Touring Runabout were not chosen for their color. Until B.F. Goodrich introduced “carbon black” into the vulcanizing process in 1910, auto tires were white.

Natural rubber pigments and zinc oxide used in the manufacturing process gave tires their while color. At the time, most cities had a downtown maximum speed limit of 10 mph.

In 1910, the B.F. Goodrich Company found that adding carbon black to the vulcanizing process dramatically improved strength and durability. The material came from controlled combustion of both oil and natural gas. Its use in tires created an immense market — initially consuming one pound of carbon black for every two pounds of rubber.

Correspondingly, as America’s automobile industry grew, so did demand for tires and carbon black. By 1931, Texas annually produced more than 200 million pounds of carbon black from just 31 plants — about 75 percent of America’s total production.

Today, most of America’s carbon black is still produced in Texas and Louisiana. Demand remains closely associated with auto tires. Cabot Corporation — founded in Pennsylvania in 1882 — is the largest U.S. producer of the intensely black petroleum product. By 2024, the company operated 43 manufacturing facilities in more than 20 countries.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Crayola Creators: Edward Binney and C. Harold Smith, Toy Trailblazers (2016); Carbon Black, Its Manufacture, Properties, and Uses (2018); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952

(2016); Carbon Black, Its Manufacture, Properties, and Uses (2018); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952 (2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “’Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/oilfield-paraffin. Last Updated: May 22, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2007.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 30, 2025 | Petroleum Products

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil scientists patented the “thermal cracking” process.

Beginning in the 1890s, the Whiting refinery of Standard Oil Company of Indiana first produced kerosene for lamps and later gasoline for autos to meet growing consumer demand.

Seventeen miles east of Chicago, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey began construction on a massive refinery complex in early May 1889. Using advanced refining processes introduced by John D. Rockefeller, it would become the largest in the United States.

BP completed a multi-year, multi-billion dollar modernization project at the Whiting refinery in 2013. Photo courtesy Hydrocarbon Processing magazine.

Once operated by Amoco, the refinery in Whiting, Indiana, was acquired by the British Petroleum Company in 1998 as part of its $48.2 billion merger with Amoco. After the acquisition, British Petroleum became BP Amoco, a name shorted to BP in 2001 after mergers with ARCO and Castrol.

The BP brand also used a lower-case bp often with the tagline “beyond petroleum” and a stylized yellow and green sun. By 2023 — and after federally mandated environmental improvements — the 1,400-acre Whiting plant refined about 435,000 barrels of oil per day.

Refining “Sour Crude”

About one month after construction of the then 235-acre refinery began, Rockefeller established a locally based subsidiary by incorporating Standard Oil Company of Indiana on June 18, 1889. The new company began processing oil at its Whiting refinery within a year.

In its early years, the Indiana refinery processed a sulfurous “sour crude” from the Lima, Ohio, oilfields — transported on Rockefeller-controlled railroads. Most Americans, already putting out their tallow candles to buy lamps fueled with whale oil, lard, or the less costly but volatile camphene, embraced a new fuel — “rock oil” soon brought skyrocketing public demand.

Rockefeller had purchased considerable amounts of production from the Lima oilfield at bargain prices. Most experts in the new petroleum industry believed the thick oil worthless. It could not be refined for a profit. The Whiting refinery, using a newly patented method, efficiently processed Ohio sour oil into high-quality kerosene.

Although gasoline was a minor by-product, two brothers in Massachusetts were building a gasoline-powered horseless carriage at about the time the refinery produced its first 125 railroad tank cars filled with kerosene. The gas-powered automobile helped relaunch the petroleum industry — see Cantankerous Combustion – 1st U.S. Auto Show.

The Standard Oil refinery in Whiting, Indiana, became the company’s most productive. Owned by BP since 1998, it has remained the largest U.S. refinery. Whiting has been home to the Northwest Indiana Oilmen since 2012.

“By the mid-1890s, the Whiting plant had become the largest refinery in the United States, handling 36,000 barrels of oil per day and accounting for nearly 20 percent of the total U.S. refining capacity,” noted historian Mark R. Wilson in the Encyclopedia of Chicago. It initially consisted of just a single facility.

Crude oil was processed into products that people and businesses needed: axle grease for industrial machinery, paraffin wax for candles, and kerosene for home lighting.

“The company grew. By the early 1900s it was the leading provider of kerosene and gasoline in the Midwest” noted Wilson on the website. “Kerosene sales would eventually falter. But with car ownership booming across the United States, demand for gasoline would only go up and up.”

More Midwest Refineries

By 1910, the refinery was connected by pipeline to oilfields in Kansas and Oklahoma, as well as Ohio and Indiana. The Whiting facility employed 2,400 workers a year later when Rockefeller was forced to break up his petroleum empire. Standard Oil of Indiana, with offices in downtown Chicago, emerged as an independent company.

Rockefeller’s Whiting scientists earlier had patented the process they called “thermal cracking” that doubled the amount of gasoline made from a barrel of oil and also boosted the octane rating. Crude oil hydrocarbons were subjected to high heat, “breaking down long-chained, higher-boiling hydrocarbons into shorter-chained, lower-boiling hydrocarbons,” according to Science Direct.

Standard Oil’s revolutionary process, which became standard practice in the refining industry, helped avert a gasoline shortage during World War I. To find its own oil supplies, Standard Oil of Indiana began its own exploration and production business, Stanolind.

In 1922, Standard Oil absorbed the American Oil Company, founded in Baltimore in 1910, and began branding products as Amoco, which later would become its company name. By 1952, Amoco was ranked as the largest domestic oil company.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the U.S. refining industry became more concentrated in Texas, Louisiana, and California.

“The Chicago region became somewhat less important as an oil-processing center than it had been during the previous 60 years,” historian Mark Wilson concluded. “Still, the area remained home to some large refineries. The largest of these plants was the one at Whiting – the same facility that had brought refining to Chicago in 1890.”

Across the border from Indiana, three major Illinois refineries also process oil in the Chicago area. At the end of 2024, the Citgo refinery in Lemont processed 177,000 barrels of oil a day; the Joliet refinery owned by ExxonMobil processed 270,000 barrels of oil a day; and the Robinson refinery of Marathon Petroleum reported a daily capacity for 253,000 barrels of oil. A fourth refinery in southern Illinois was constructed in 1918 by Shell.

The BP Whiting Refinery on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan in 2024 processed 346,500 barrels of oil daily into millions of gallons of gasoline/fuel — and thousands of barrels of asphalt.

The smaller Wood River Refinery has its own museum.

Wood River Refining Museum

Fifteen miles north of St. Louis, Missouri, the Wood River Refinery at Roxana, Illinois, can boast of its own museum. The refinery is owned by Phillips 66 and the Canadian company Cenovus Energy.

“The Wood River Refinery History Museum is located in front of the refinery on Highway 111 in Wood River, Illinois,” the museum notes. “There are four buildings in our complex, so to see most of our collection, plan on spending some time.”

Meanwhile, the historic Whiting refinery has supported a baseball team — the Northwest Indiana Oilmen, one of eight teams in the Midwest Collegiate League, a pre-minor league (see more petroleum-related baseball teams in Oilfields of Dreams).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (2004); Whiting and Robertsdale – Images of America

(2004); Whiting and Robertsdale – Images of America (2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Standard Oil Whiting Refinery.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/standard-oil-whiting-refinery. Last Updated: May 2, 2025. Original Published Date: June 15, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 20, 2025 | Petroleum Products

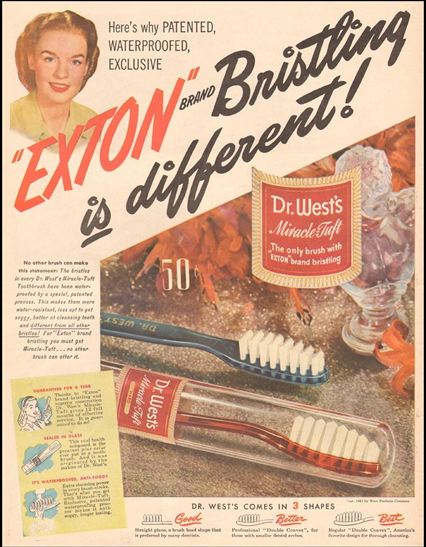

Revolutionary DuPont lab product first used commercially in 1938 for toothbrush bristles.

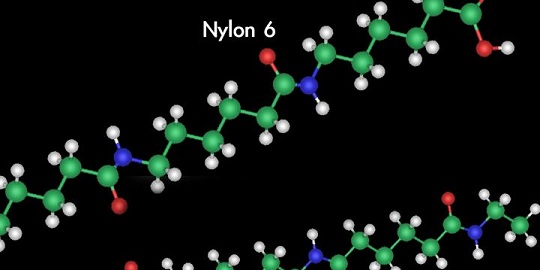

The world’s first synthetic fiber was the petroleum product “Nylon 6,” discovered in 1935 by a DuPont chemist who produced the polymer from chemicals found in oil.

DuPont Corporation foresaw the future of “strong as steel” artificial fibers. The chemical conglomerate had been founded in 1802 as a Wilmington, Delaware, manufacturer of gunpowder. The company would become a global giant after its scientists created durable and versatile products like nylon, rayon and lucite.

“Women show off their nylon pantyhose to a newspaper photographer, circa 1942,” noted historian Jennifer S. Li in “The Story of Nylon – From a Depressed Scientist to Essential Swimwear.” Photo by R. Dale Rooks (1917-1954).

The world’s first synthetic fiber — nylon — was discovered on February 28, 1935, by a former Harvard professor working at a DuPont research laboratory. Called Nylon 6 by scientists, the revolutionary carbon-based product came from chemicals found in petroleum.

Chemists called the man-made fiber Nylon 6 because chains of adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contained six carbon atoms per molecule.

Professor Wallace Carothers had experimented with artificial materials for more than six years. He previously discovered neoprene rubber (commonly used in wet suits) and made major contributions to understanding polymers — large molecules composed in long chains of repeating chemical structures.

Polymer Chains

Carothers, 32, created fibers when he combined the chemicals amine, hexamethylene diamine, and adipic acid. His experiments formed polymer chains using a process in which individual molecules joined together with water as a byproduct. But the fibers were weak.

A PBS series, A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries, in 1998 noted Carothers’ breakthrough came when he realized, “the water produced by the reaction was dropping back into the mixture and getting in the way of more polymers forming. He adjusted his equipment so that the water was distilled and removed from the system. It worked!”

DuPont named the petroleum product nylon — although chemists called it Nylon 6 because the adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contain six carbon atoms per molecule.

“Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” noted a 1938 ad.

Each man-made molecule consists of 100 or more repeating units of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms, strung in a chain. A single filament of nylon may have a million or more molecules, each taking some of the strain when the filament is stretched.

There’s disagreement about how the product name originated at DuPont.

“As to the word nylon, it’s actually quite arbitrary. DuPont itself has stated that originally the name was intended to be No-Run (that’s run as in the sense of the compound chain of the substance unravelling), but at the time there was no real justification for the claim, so it needed to be changed,” noted Chris Nickson in a 2017 website post, Where Does the Name Nylon Originate?

Toothbrush Bristles

The first commercial use of this revolutionary petroleum product was for toothbrushes.

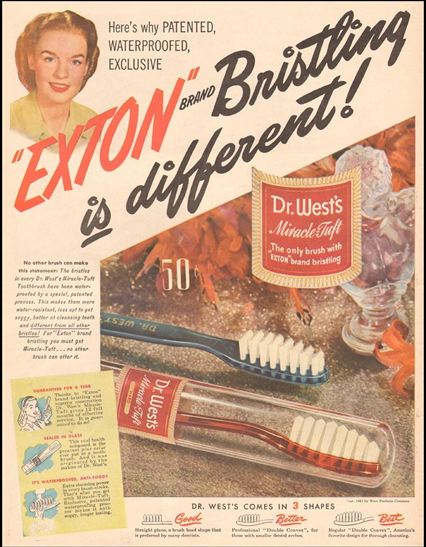

On February 24, 1938, the Weco Products Company of Chicago, Illinois, began selling its new “Dr. West’s Miracle-Tuft” — the earliest toothbrush to use synthetic DuPont nylon bristles.

First used for toothbrush bristles, nylon women’s stockings were promoted in a DuPont 1948 ad.

Americans will soon brush their teeth with nylon — instead of hog bristles, declared an article in the New York Times. “Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” explained a 1938 Weco Products advertisement in Life magazine.

“Today, Dr. West’s new Miracle-Tuft is a single exception,” the ad proclaimed. “It is made with EXTON, a unique bristle-like filament developed by the great DuPont laboratories, and produced exclusively for Dr. West’s.”

Pricing its toothbrush at 50 cents, the Weco Products Company guaranteed, “no bristle shedding.” Johnson & Johnson of New Brunswick, New Jersey, will introduce a competing nylon-bristle toothbrush in 1939.

Nylon Stockings

Although DuPont patented nylon in 1935, it was not officially announced to the public until October 27, 1938, in New York City.

A DuPont vice president unveiled the synthetic fiber — not to a scientific society or industry association — but to 3,000 Women’s Club members gathered at the site of the upcoming 1939 New York World’s Fair.

During WWII, nylon was used as a substitute for silk in parachutes.

“He spoke in a session entitled ‘We Enter the World of Tomorrow,’ which was keyed to the theme of the forthcoming fair, the World of Tomorrow,” explained DuPont historian David A. Hounshell in a 1988 book.

The petroleum product was an instant hit, especially as a replacement for silk in hosiery. DuPont built a full-scale nylon plant in Seaford, Delaware, and began commercial production in late 1939. The company purposefully did not register “nylon” as a trademark – choosing to allow the word to enter the American vocabulary as a synonym for “stockings.”

Women’s nylon stockings appeared for the first time at Gimbels Department Store on May 15, 1940. World War II would remove the polymer hosiery to make nylon parachutes and other vital supplies.

Nylon would become far and away the biggest money-maker in the history of DuPont. The powerful material from lab research led company executives to derive formulas for growth, according to Hounshell in The Nylon Drama.

“By putting more money into fundamental research, Du Pont would discover and develop ‘new nylons,’ that is, new proprietary products sold to industrial customers and having the growth potential of nylon,” Hounshell explained in his 1988 book.

Carothers did not live to see the widespread application of his work — in consumer goods such as toothbrushes, fishing lines, luggage and lingerie, or in special uses such as surgical thread, parachutes, or pipes — nor the powerful effect it had in launching a whole era of synthetics.

Devastated by the sudden death of his favorite sister in early 1937, Wallace Carothers committed suicide in April of that year. The DuPont Company would name its research facility after him.

The DuPont website notes that the invention of nylon changed the way people dressed worldwide and made the term ‘silk stocking’ obsolete (once an epithet directed at the wealthy elite). Nylon’s success encouraged DuPont and other companies to adopt long-term strategies for products developed from research.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History (2019); Enough for One Lifetime: Wallace Carothers, Inventor of Nylon (2005); The Nylon Drama (1988). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/petroleum-product-nylon-fiber. Last Updated: February 21, 2025. Original Published Date: February 23, 2014.

View Post

by Bruce Wells | Jan 16, 2025 | Petroleum Products

When Phillips Petroleum scientists invented a new plastic in the early 1950s, getting it from lab to market proved difficult. Enter Wham-O.

Research scientists in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1951 discovered how to make a durable, high-density polyethylene, and the marketing executives at their oil and natural gas company named it Marlex. But Phillips Petroleum sales reps searched in vain for buyers of the new plastic until the Wham-O toy company found it ideal for making hoops and flying platters.

Prompted by a post World War II boom in demand for plastics, Phillips Petroleum Company invested $50 million to bring its own miracle product — Marlex — to market in 1954. With a high melting point and tensile strength, the synthetic polymer would stand out from the company’s thousands of patents.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jan 14, 2025 | Petroleum Products

“New Perfection” kerosene stoves once competed with coal and wood-burning stoves in rural kitchens.

In the early 1900s, a foundry in Cleveland, Ohio, began manufacturing and selling an alternative to coal or wood-burning cast iron stoves. Thanks to a marketing partnership with Standard Oil Company, millions of rural kitchens would cook with kerosene-burning stoves.

America’s energy future changed after 1859 when a new “coal oil” (kerosene) was refined from petroleum purposefully extracted from wells drilled near Oil Creek, Pennsylvania.

A Cleveland foundry president in 1901 approached John D. Rockefeller about a new, kerosene-fueled alternative to cast iron home stoves like this one.

(more…)

(2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.