by Bruce Wells | Jan 10, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

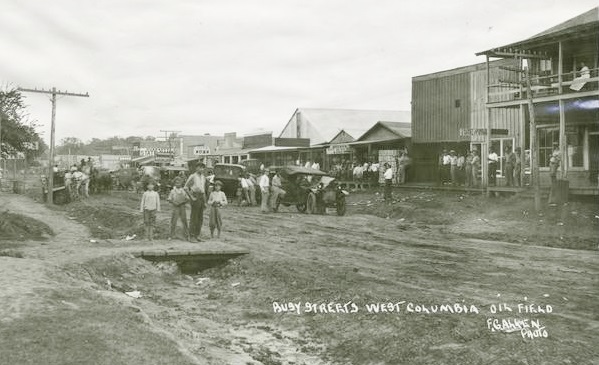

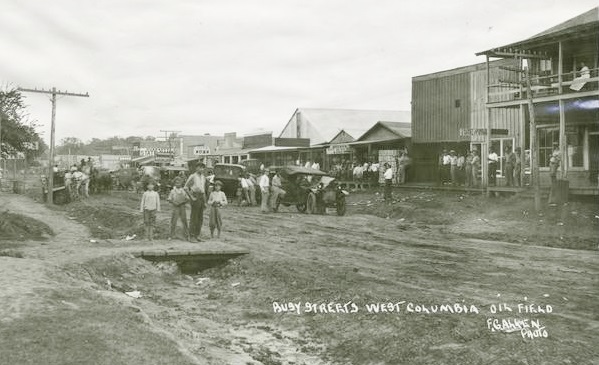

Lucky Jim Oil Company was created in March 1919 to pursue opportunities in the newly discovered West Columbia oilfield in Brazoria County, Texas (visit the Columbia Historical Museum in West Columbia to learn more about the first capital of the Republic of Texas).

The Brazoria County oilfield, 50 miles southwest of Houston, “was the youngest of the first rank salt dome oilfields of the Texas-Louisiana coastal region, and at present is the most productive of these fields,” reported the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) in 1921.

Wind knocked down the first derrick of a Lucky Jim Oil Company well drilled in 1919. The well reached 3,340 feet before the company gave up – and reorganized as the Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company.

Like many competing exploration companies formed during Texas drilling booms, Lucky Jim Oil Company did not survive its first dry hole. A Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company fared no better.

West Columbia field

Wildcatters had become interested in the West Columbia after oil discoveries on a lease owned by a former Texas governor. Gov. J.S. “Big Jim” Hogg first thought oil might be there and leased the land in 1901 (learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells).

When the Hogg No. 2 well was completed at 600 barrels of oil a day in January 1918, speculators rushed to lease nearby acreage. The 20-square-mile oilfield yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918.

The Hogg discovery wells led to a local boom that attracted inexperienced, even fraudulent, drilling companies that would not long survive. They planned to drill near property with proven oil production.

Advertisements appeared in Texas newspapers that included $10 per share stock promotions enticing investment in the West Columbia oilfield — with a promise to pay out 75 percent of any net earnings to shareholders. The ads assured investors of early dividends and admonished, “Buy Today, Tomorrow May Be Too Late.”

The Texas Company (later Texaco) was among companies that found success in the 20-square-mile oilfield in Brazoria County. The field yielded more than 119,000 barrels of oil in 1918 alone.

Hedging against a dry hole and gambling on higher oil prices, Lucky Jim Oil declared in 1919, “We have immense holdings that we should be able to sell out on the present rise of prices in West Columbia, and pay our stockholders three or four for one on their investment without drilling a well.”

With funding from stock sales, the company was able to begin drilling its first well, the Brown No. 1, proclaiming it to be “within 1,800-feet of the Texas Company’s 20,000 barrel gusher.”

Drilling progressed for a few months until the derrick reportedly collapsed in high winds during a September storm. After rebuilding the wooden structure and resuming drilling, the well reached 3,340 feet. It was an expensive dry hole.

Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company

Within a month of the failed exploratory well, a reorganized Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company made its first appearance and tried again to secure funding to launch drilling operations in the crowded West Columbia oilfield.

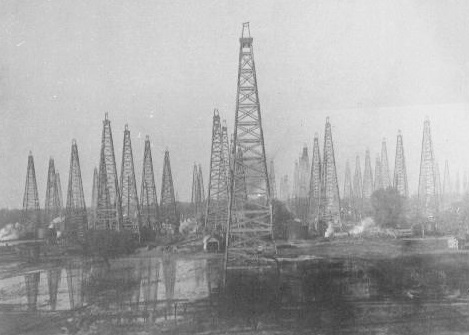

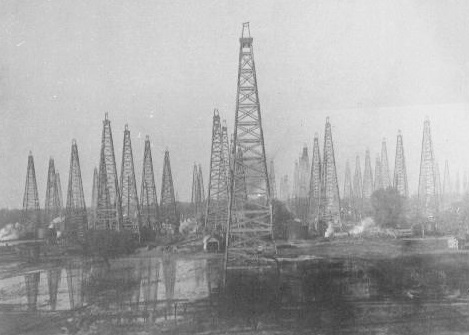

A drilling boom resulted in the West Columbia oilfield reaching its annual peak production of 12.5 million barrels of oil a few years after its discovery.

The new company did not succeed in raising enough capital and soon disappeared, along with many other such “poor boy” operations in South Texas at the time. Only larger companies could absorb costs of a dry hole and continue drilling.

The Texas Company (later Texaco) – after drilling several dry holes in the West Columbia field – in July 1920 brought in the Abrams No. 1 well, which produced 26,500 barrels a day for six weeks (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

By 1921, the West Columbia field reached its peak annual production of 12.5 million barrels of oil — but by then the Lucky Jim Oil Company and Lucky Jim Junior Oil Company were both history.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936 (2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lucky Jim Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/lucky-jim-oil-company. Last Updated: September 4, 2021. Original Published Date: September 8, 2015.

.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Boom and bust of an obscure mid-continent petroleum company began in 1917.

The International Petroleum Register noted formation of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company as a Delaware corporation in 1917. With capitalization of $5 million in common stock authorized and more than $734,000 issued, the company obtained leases in Muskogee, Tulsa, Rogers, and Okmulgee counties in Oklahoma, and in Allen County, Kansas.

Major north Texas oilfield discoveries in Electra (1911) and Ranger (1917) attracted petroleum companies to the mid-continent. As oil demand soared during World War I, hundreds of new exploration and productions companies formed — and sought investors. Most of these companies would not survive.

By 1919, Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining’s lease ownership had expanded to 10,313 acres with an additional 815 acres from its acquisition of Tulsa Union Oil Company. About this time, all of the company’s petroleum production was sold to Prairie Oil and Gas Company.

Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining meanwhile continued drilling for oil in Coffee County, Kansas, and elsewhere, and the company’s estimated production reached 10,000 barrels of oil each month — a promising development for investors. The financial magazine United States Investor added a positive endorsement in May 1920 after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining reported production of 27,000 barrels of oil worth $65,000.

“It appears that this company is further along the road to development that a great many of the new oil companies, though whether its shares at the present offering price of $2.50 on the basis of a $1 par represent an extravagant price, cannot be told until further developments have occurred,” United States Investor reported.

However, six months later, the company’s shares were selling for less than 14 cents. Records of what went wrong are obscure. There are references to a convoluted business venture with another oil company. The deal was orchestrated by New York financier Mrs. Ada M. Barr after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining had failed in January 1921.The next month, after being put in the hands of a receiver, the company’s assets were sold for $87,400.

The buyer was Mrs. Barr, who soon would be enveloped in controversy and litigation of her own.

Acorn Petroleum Corporation, represented by Mrs. Barr, offered bonds in the amount of $150,000 of Acorn Petroleum Corporation on the basis of $250 in bonds for each $1,000 of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining stock held.

“The new company is operating the properties and has twenty-three producing wells, giving about ninety barrels of oil a day. The present low price for oil does not enable the company to earn sufficient income to pay interest on its bonds,” United States Investor noted. “Mrs. A.M. Barr, who arranged the financing of the new company, says that as soon as oil advances to a price that will permit, accrued interest on the bonds and dividends on the stock will be paid.”

But they weren’t.

By March 1923, investor Lewis H. Corbit filed a petition on behalf of a large number of local purchasers of stocks in the Acorn Petroleum Corporation of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The petition in the United States District court sought to determine the value of the local holdings, which represent an investment of approximately $100,000.

According to records, “In his complaint, asking for an investigation, Corbit alleges a stock, fraud in which $ 500,000 is involved. Certificates of shares held here were sold by a Mrs. A. M. Barr, it is disclosed in the petition.”

Further financial records and other details about Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company, Acorn Petroleum Corporation, and Mrs. Ada M. Barr can be research through the Library of Congress’ online Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

___________________

The stories of exploration and production (E&P) companies joining U.S. petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Somerset, Texas, was a quiet farming community about 15 miles from San Antonio on the Artesian Belt Railroad in 1913 when one of the town founders, Carl Kurz, discovered oil while drilling for water. The same thing had happened at Corsicana in 1894, bringing the first Texas oil boom.

The Somerset oilfield, which would extend south of Pleasanton, became known as “the largest known shallow field in the world at that time.” It joined other Texas discoveries making headlines since the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, almost 2,000 miles from Somerset, a group businessmen formed New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate, one of many companies to explore for oil southwest of San Antonio. Part of their incentive might have been a well owned by W.C. Steubing near the Somerset field.

Drilling the exploratory well with a rotary rig began on September 30, 1918, two miles southeast of Somerset. But three months and 1,688 feet deep later, Steubing’s well, the Sarah Smith No. 1, well proved to be an expensive “dry hole.” The New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate incorporated in Massachusetts with capitalization of $1 million and 200,000 shares of its stock with a nominal par value of $5.

“It is announced by Judge M.L. Barr, of Springfield, Mass., who recently arrived here to direct the oil operations of the New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate in the Somerset field, adjacent to San Antonio, that the company will proceed immediately to drill 100 wells on its leases,” noted Oil Paint and Drug Reporter in April 18, 1921.

The syndicate’s holdings included 330 acres from Glasscock Leasing Company, Clover Leaf Oil Company and others, the publication reported. Some 100 acres were leased near Fort Stockton and 30,000 acres of leases signed in Llano and Mason counties.

Back in Northampton, Massachusetts, more than 75 percent of shareholders were present personally or by proxy to elect their board of trustees for the New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate: Frederick L. Haskins, Thomas Brooks, and James E. Ryan.

The Petroleum Age trade publication added that syndicate trustee Frederick L. Haskins, “has taken over a considerable acreage in Somerset, and has announced that in addition to developing the shallow oil, a deep test will be started as soon as a contract can be made.”

At the time, the Somerset oilfield had nearly 300 shallow wells producing an aggregate of about 2,500 barrels of high-gravity crude oil daily.

But in January 1922, the United States Investor report the likely financial demise of the New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate. “We have seen nothing lately on this company and believe that very little market exists for the stock, as is the case of so many companies which have arisen within a year or two,” the business editors proclaimed.

Although New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate began rigging up to drill the Sarah Smith No. 2 well near the original W.C. Steubing well site, progress was slow. The Oil Weekly For several months, tracked the well’s status, but apparently nothing happened beyond erecting the drilling derrick.

The Texas Railroad Commission might have historical information about New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate. Another potential source is the Massachusetts Corporations Division.

———–

The stories of exploration companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2021 AOGHS.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 27, 2020 | Petroleum Companies

Seaboard Oil & Gas Company is sometimes confused with a different venture, Seaboard Oil Company.

Seaboard Oil & Gas Company organized in March 1918 capitalized at $1.5 million. It established offices in Oklahoma. By 1920, the company reported 33 producing oil wells and the income resulted in dividends to investors and the purchase of additional leases and assets.

However, a dispute with the Bank of Oklahoma resulted in extended litigation. Seaboard Oil & Gas nonetheless acquired Mid-Texas Petroleum Company and its producing properties in Young County, Texas. Buy 1922, the company’s profits were substantially diminished because of the reduced market price of oil. Investment analysts urged caution.

“The last statement of the company available to us did not indicate so strong a financial position as to warrant recommendation by us that this stock is deserving of consideration as a speculation at existing prices,” reported United States Investor.

In 1924, the company removed its $5 par value from issued stock, pending listing of a new stock of no par value. The company’s fortunes continued to fade and in 1926, it tried to raise additional funding through an increase in capitalization to $3.5 million with a corresponding stock marketing push.

Stocks were sold as late as 1930, but the company lost its charter and went out of business. No shareholder equity survived at that time. Old Seaboard Oil & Gas Company stock certificates have only collectible value. The other similarly named venture, Seaboard Oil Company, by way of mergers and acquisitions, became part of The Texas Company in 1958.

Read more about companies that rushed to Texas oilfields in the 1920s in Pump Jack Capital Of Texas.

___________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2021 Bruce A. Wells.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 24, 2020 | Petroleum Companies

Going broke where a billion-barrel oilfield would be discovered in the 1870s.

When the Seneca Oil Company completed the first U.S. oil well along Oil Creek at Titusville, demand for crude oil from northwestern Pennsylvania boomed. The 1859 oil discovery launched a new industry, which soon constructed refineries to produce kerosene from oil instead of coal (coal oil) as a safe, inexpensive lamp fuel.

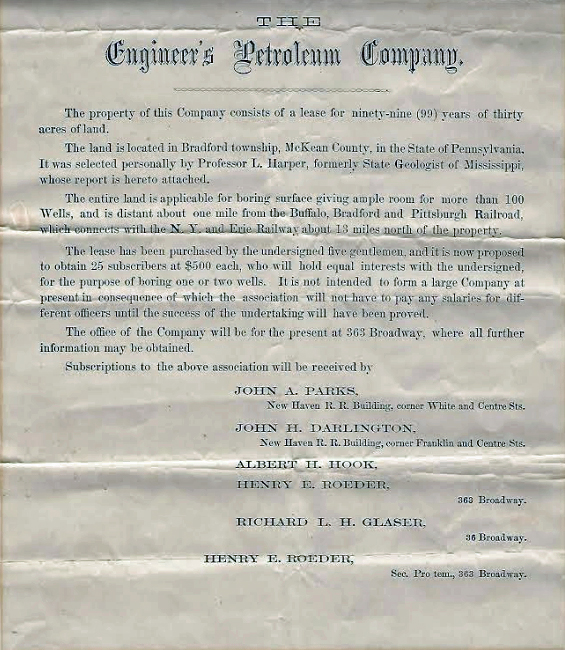

Engineer’s Petroleum Company, one of the early companies to explore east of Titusville, decided to search in the hills around the remote town of Bradford, near the New York border. Armed with detailed geologic studies, the company believed it had an edge for finding oil.

In 1836, famed scientist Samuel Prescott Hildreth published a geological study on the possibilities for salt production in southeastern Ohio. The respected pioneer physician and scientist had left Massachusetts in 1898 to settle in Marietta, along the banks of the Ohio River. His expertise helped salt well drillers, who were familiar with the “making hole” technologies the new petroleum industry needed.

Oil, Bane of Brine Drillers

Hildreth’s geological study, “Observations on the Bituminous Coal Deposit for the Valley of the Ohio, and the Accompanying Rock Strata,” identified anticlinal structural traps as features linked to drilling successful brine wells. Intended to help the search for that valuable food-preserving resource, his report’s revelation about the anticlines later would be important for many Ohio oil discoveries.

Importantly, Hildreth reported anticlinal rock formations were frequently associated with oil deposits. This was a warning for Ohio salt well drillers, who considered petroleum a problem, not a resource (see this article about a Kentucky salt driller’s oil well).

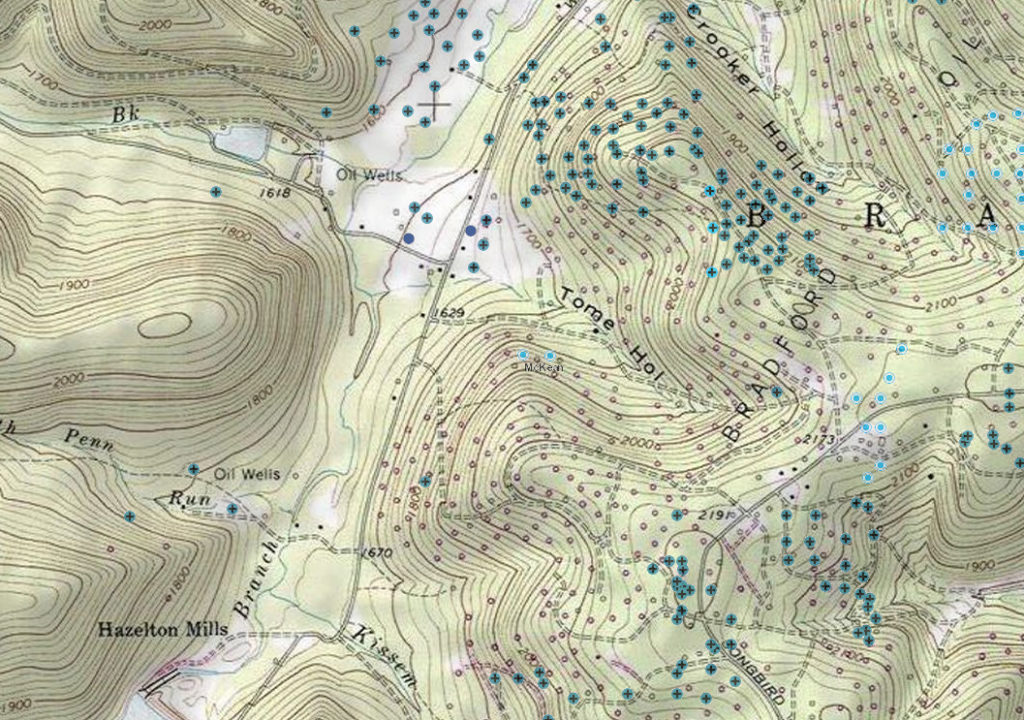

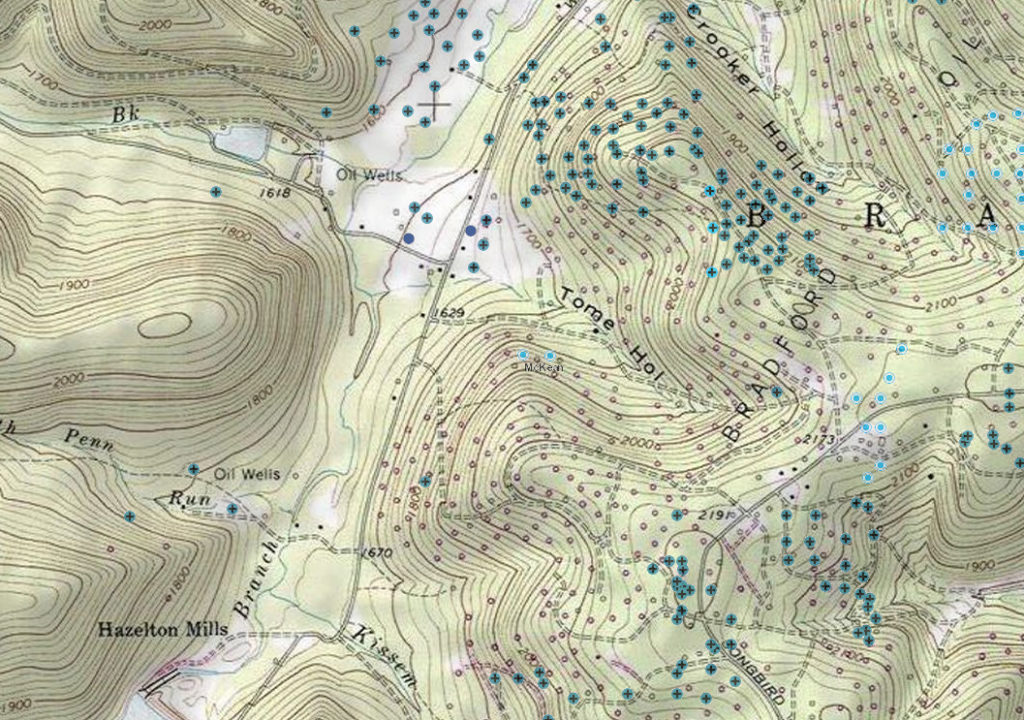

“This dale is evidently formed by upheavals which have taken place towards the end of the Devonian period,” explained the geologist seeking a site to drill for oil near Bradford, Pennsylvania. Prospective site’s topography image courtesy Pennsylvania Department of Natural Resources online mapping.

After Pennsylvania oil discoveries, exploration companies like Engineer’s Petroleum rushed to the state – where drilling equipment and lease prices soared. Hundreds of exploration companies organized in Titusville, Franklin, and Oil City as financiers, speculators, and drillers sought to invest in this new “black gold” industry.

In 1865, after a United States Oil Company oil discovery created the notorious boom town of Pithole, half-acre leases nearby sold for $3,000 each (about $45,000 in 2020 dollars). Fortunes were made or lost or squandered – most famously at the time by “Coal Oil Johnny”.

Under-capitalized speculators had to look to more distant, unproven territory, including Engineer’s Petroleum Company. About 65 miles northeast of Pithole (thorough today’s scenic Allegheny National Forest), a few exploratory wells had been drilled in McKean County, but few believed commercial quantities of oil could be found; leases could be had for at little as six cents an acre.

Falling into Anticlinal Traps

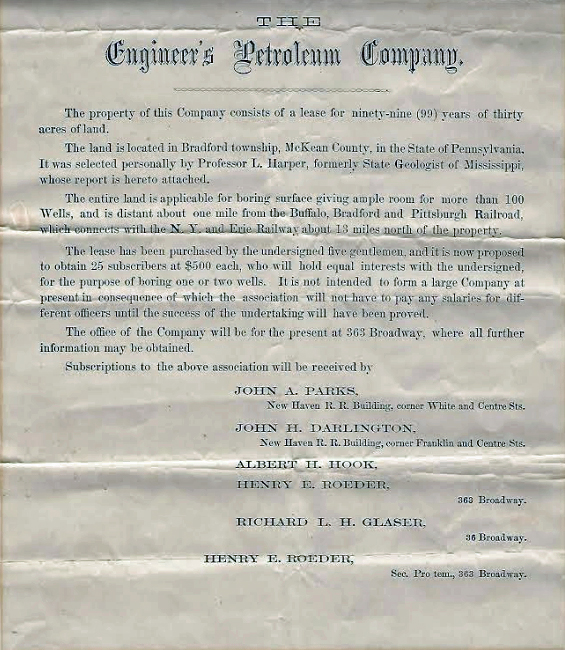

To attract investors, Engineer’s Petroleum Company cited geological reports about likely sites for successful oil wells, accompanied by this document offering lease units for sale. Document image courtesy Charles Laser.

To attract investors, Engineer’s Petroleum Company cited the best geological science of the day. Company executives also sought the well-regarded expertise of former Mississippi State Geologist Lewis Harper. The geology professor used Hildreth’s long-standing structural trap guidance to select a promising 30-acre site, “giving ample room for more than 100 oil wells.”

The exploration company selected a site southwest of Bradford Township, on a tributary of the West Bank of Tunungwant Creek. “This dale is evidently formed by upheavals which have taken place towards the end of the Devonian period, it is not simply a dale formed by the flowing of water run down from the hills,” Harper noted, further explaining:

“If now, before the upheaval of these hills from a horizontal position, petroleum had been formed or such animal or vegetable matter had been accumulated which gives origins to petroleum, this must have run down from the inclined planes and accumulated in the ground which has not been upheaved in the dale formed by the three hills.”

Unfortunately for Engineer’s Petroleum Company and its investors, Professor Harper and his colleagues’ theories were wrong about Pennsylvania’s anticline petroleum geology. Pennsylvania oilfields were mostly found in formations very different from those in Ohio. Historian and author Ray Sorenson has noted the misinterpretation (see Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology) by pointing out, “theories of trapping did not work in the absence of anticlines.”

Early exploration company executives had learned geologists’ theories for finding oil were often no better than traditional creekology (and helpful oil seeps), dowsers, witching, or blind luck. James C. Donnell, later president of the Ohio Oil Company, began his career in Bradford’s early oilfields and declared, “The day The Ohio has to rely on geologists, I’ll get into another line of work.”

Experience and the science of petroleum geology advanced together over coming years, improving the odds of drilling and completing a successful well. Donnell had to revise his opinion of “college boys” when Ohio Oil Company’s first geologist, C.J. Hares, discovered 19 oil and natural gas fields. Donnell declared Hares to be, “the greatest geologist in the world.”

Engineer’s Petroleum Company, which never found oil at its “dale formed by the three hills,” would go bankrupt. But it would be proved right to have looked in the Bradford area. In 1871, another speculative venture, the Foster Oil Company, drilled a series of small producers east of the Main Branch of Tunungwant Creek, about five miles north of the old Engineer’s Petroleum site.

The Penn-Brad Museum and Historical Oil Well Park is located just south of Bradford on Route 219, near Custer City. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Foster Oil Company wells revealed what ultimately led to America’s first billion-barrel oilfield. Production from the Bradford field peaked in 1881 when it produced more than 27 million barrels of oil – more than 75 percent of the world’s total output that year.

Today, in Custer City, a few miles south of Bradford, the Penn-Brad Oil Museum preserves “the philosophy, the spirit, and the accomplishments of a little-known oil country community — taking visitors back to the early oil boom times of ‘The First Billion Dollar Oil Field.'”

In addition to its historic oilfield – and being home to Zippo Manufacturing Company since the early 1930s – Bradford also boasts the world’s oldest continuously operating petroleum refinery; the American Refining Group, Inc. began processing 10 barrels of Pennsylvania crude oil a day in 1881.

_______________________________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2020 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Engineers Petroleum Company.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/engineers-petroleum-company. Last Updated: March 24, 2020. Original Published Date: March 24, 2020.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 11, 2020 | Petroleum Companies

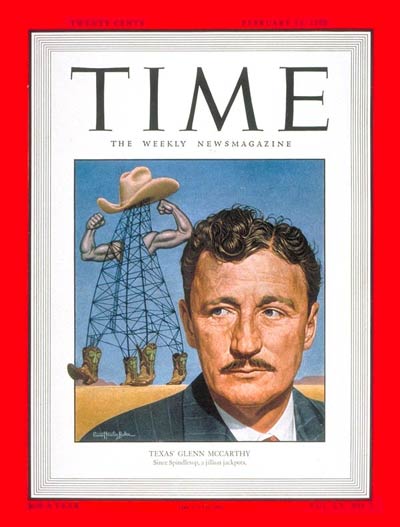

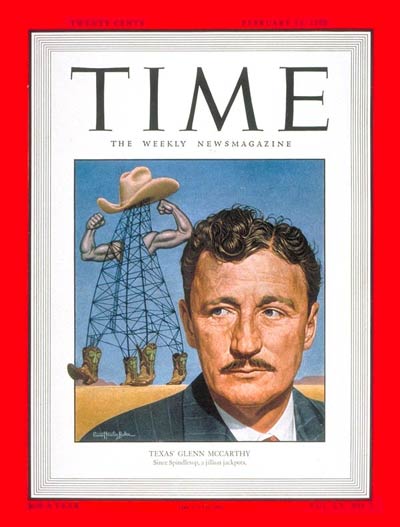

Just two years after being featured on the cover of TIME in 1950, Texas wildcatter “Diamond” Glenn McCarthy was in serious financial trouble with one of his many oil ventures. On April 8, 1952, the Baytown (Texas) Sun reported, ”Glenn McCarthy stepped down today as chairman of the board of the firm which made him a multimillionaire – but couldn’t pay its bills.”

The McCarthy Oil & Gas Company mortgage debt was $34 million, including his beloved 18-story, 1,100-room Shamrock Hotel, which “introduced Houston as a dynamic city of the future to the rest of the nation,” the Houston Business Journal later proclaimed. McCarthy Oil & Gas was lost to the Equitable Assurance Society of the United States, prompting McCarthy’s ouster.

Texas independent producer Glenn McCarthy appeared on the February 13, 1950, cover of TIME.

Undeterred, the Texas wildcatter who had discovered 11 oilfields by 1945 announced formation of a new company, Glenn McCarthy, Inc. He would seek new oil and natural gas fields in Bolivia. His plan was that the new firm would be a “poor man’s” company with 60 million shares to be sold at $2 each, encouraging “little investors” to gamble on his wildcatting reputation.

In October 1953, McCarthy offered the first 10 million shares of Glenn McCarthy, Inc. to the public. The company prospectus noted it was a speculative venture, with its principle assets being petroleum leases in Bolivia totaling 970,000 acres in the Andes foothills.

McCarthy intended to market the oil and natural in Bolivia, Argentina, and Uruguay, but not in the distant United States. Newspapers reported McCarthy had launched, “a new effort to climb from ‘rags to riches,’ a route over which he’s passed several times in both directions.”

A blitz of sales promotions and mail-in stock order forms reached newspapers all over Texas. Then came good news from South America: In September 1954, Glenn McCarthy, Inc., completed its first Bolivian oil well. The discovery was on the Los Monos concession and produced 100 barrels of oil a day in addition to some natural gas. The well’s depth was reported to be between 9.000 feet and 12,000 feet – the deepest well in Bolivia.

However, the lack of pipeline and rail infrastructure prohibited effective marketing of the crude oil to refineries (a frequent problem for wells drilled in remote areas, see Million Barrel Museum). Lack of infrastructure proved disastrous for Glenn McCarthy, Inc.

As described in The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes, by Bryan Burrough, “McCarthy dragged himself back from Bolivia in 1957, bruised, battered, and, if not exactly penniless, no longer a rich man; unable to build a pipeline to transport the natural gas he had discovered, he sold his Bolivian interests to a group of American companies for $1.5 million, much of which he used to repay debts.“

Although McCarthy recovered somewhat financially, the Glenn McCarthy, Inc., passed into history, joining the legend of “Diamond Glenn” and leaving its collectible stock certificates. McCarthy and his wife Faustine lived a quiet life in a modest two-story house near La Porte, Texas. The once famous Texas wildcatter died the day after Christmas, 1988.

_______________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2021 AOGHS. All rights reserved.

(2000); Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.