The ingenuity of a skilled machinist and a Texas wildcatter created a device to stop gushers.

Petroleum drilling and production technologies, among the most advanced of any industry, evolved as exploratory wells drilled deeper into highly pressurized geologic formations. One idea began with a sketch on the sawdust floor of a Texas machine shop.

On January 12, 1926, James S. Abercrombie (1891-1975) and Harry S. Cameron (1872-1928) received their first patent for a hydraulic ram-type blowout preventer (BOP). Their invention would become a vital technology for ending dangerous oil and natural gas gushers — and saving lives.

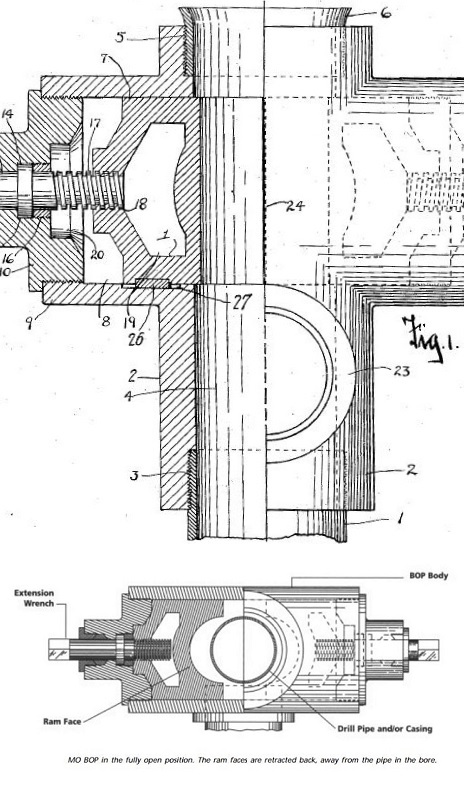

“The object of our invention is to provide a device designed to be secured to the top of the casing while the drilling is being done and which will be adapted to be closed tightly about the drill stem when necessary,” they noted in their 1922 U.S. patent application, which was approved four years later.

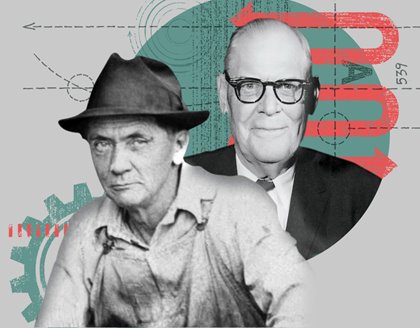

James Abercrombie and Harry Cameron in 1926 were awarded a U.S. patent (No. 1,569,247) for their Cameron Iron Works manually operated ram-type BOP.

“In 1920, Abercrombie and Cameron formed Cameron Iron Works. There, the two developed Abercrombie’s idea for a “ram-type” blowout preventer that would use hydrostatic pistons (rams) to clamp the drill stem and create a seal against well pressure during a blowout,” notes the National Inventors Hall of Fame, which in 2022 inducted Abercrombie and Cameron.

Wells that erupted into gushers were dramatic but dangerous and wasteful. The ram-type blowout preventer brought a dramatic change. By the time of the 1956 movie “Giant,” where actor James Dean celebrated in a rain of oil, most gushers had ended.

Spindletop Hill

Well control technologies for America’s oilfields began soon after the first U.S. oil well of 1859, which produced from a depth of just 69.5 feet. There was little understanding of petroleum geology as drilling depths increased and brought unpredictable downhole pressures.

Perhaps the most famous high-pressure blowout occurred at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, Texas. Shortly after 10 a.m. on January 10, 1901, a three-man crew was drilling when a six-inch stream of oil and natural gas erupted 100 feet into the air. It was the first U.S. well to produce 100,000 barrels of oil per day.

Production from the giant Texas oilfield would prove important for an increasingly gasoline-hungry nation — the first U.S. auto show had taken place in New York City less than two months earlier.

The 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill, Texas, was the first U.S. well to produce 100,000 barrels of oil per day. The iconic photo by Frank Trost of Port Arthur includes Anthony Lucas standing at right.

A Beaumont newspaper described the discovery well drilled by Anthony F. Lucas (and long predicted by Pattillo Higgins of the Gladys City Oil, Gas, and Manufacturing Company) as an “Oil Geyser — Remarkable Phenomenon South of Beaumont — Gas Blows Pipe from Well and a Flow of Oil Equaled Nowhere Else on Earth.”

It took nine days and 500,000 barrels of oil before a shut-off valve for the well could be affixed to the casing to stop the powerful flow of oil and natural gas. The record-setting petroleum production came from a salt dome geologic formation, as Lucas knew Higgins had predicted.

News and images of the “Lucas Gusher” would circulate nationwide, attracting more investors and creating new exploration, production, and refining companies.

Learn more by visiting the Spindletop/Gladys City Boomtown Museum in Beaumont.

Inventing the BOP

Patent records abound with inventors’ efforts to find a solution to controlling the underground pressure encountered when drilling. It took a successful wildcatter’s ingenuity to finally devise a workable “blowout preventer.”

James Abercrombie (1891–1975) of Huntsville, Texas, had personal experience with the dangers of uncontrollable blowouts, having narrowly escaped one himself:

“With a roar like a hundred express trains racing across the countryside, the well blew out, spewing oil in all directions,” noted one witness. “The derrick simply evaporated. Casings wilted like lettuce out of water, as heavy machinery writhed and twisted into grotesque shapes in the blazing inferno.”

Abercrombie started in the oilfields as a roustabout in 1908 working for the Goose Creek Production Company and by 1920 owned several rigs in south Texas. He met Harry Cameron (1872–1928) in the machine shops of the Cameron-Devant Company, where Abercrombie was a frequent customer. The two men soon became friends and business partners.

In 1920, Abercrombie and Cameron formed Cameron Iron Works to repair drilling rigs and sell supplies and parts to oilmen. They employed five men with two lathes, a drill press, and hand tools. They named the company Cameron because Abercrombie already had two companies with his name.

Abercrombie said of his friend, “Harry Cameron was a great machine-tool man. You could give him a piece of iron and he could make just about anything you wanted.”

Sketched in Sawdust

James Abercrombie came up with the idea for a “ram-type” blowout preventer — using rams (hydrostatic pistons) to close on the drill stem and form a seal against the well pressure. He sketched his idea on the sawdust floor of the Cameron Iron Works machine shop in Humble, Texas.

Independent producer James Abercrombie (right) and machinist Harry Cameron helped stop eruptions due to inadequate pressure control. Photo courtesy American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Abercrombie and Cameron worked out the details, fabricating simple, rugged parts at the shop. When installed on a wellhead, the rams could be closed off, allowing full control of pressure during drilling and production.

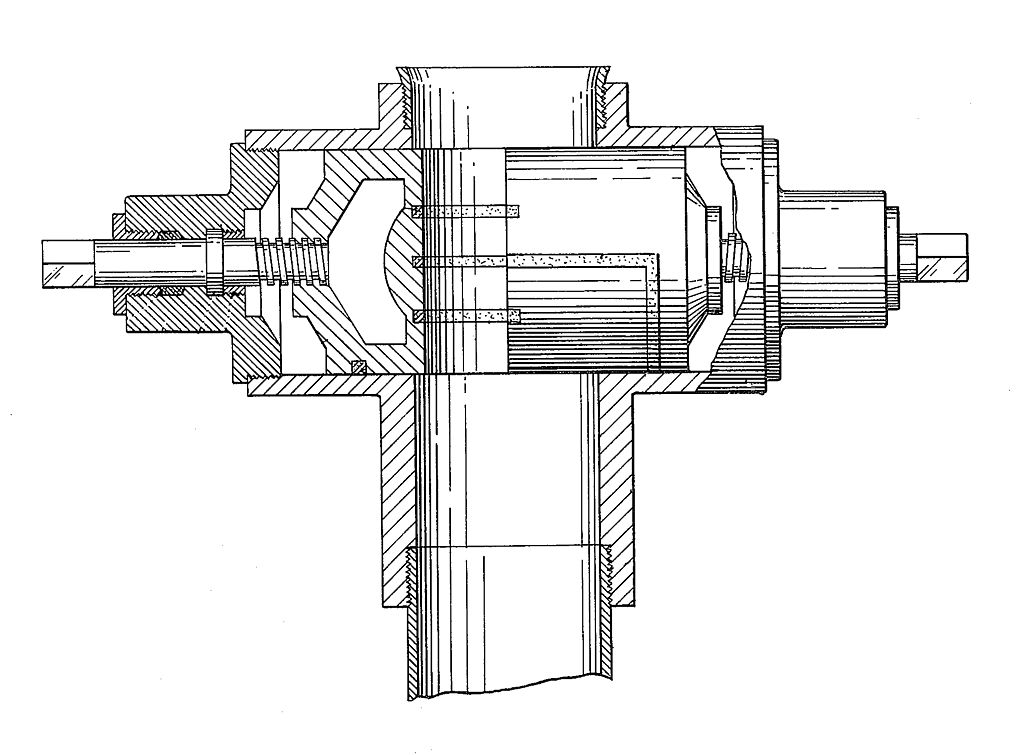

In April 1922, they filed their patent application for a Type MO BOP (manually operated blowout preventer that could withstand pressures of up to 3,000 psi). Subsequent improvements continued to increase the device’s capability, according to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers,

The design was summed up in words from the application, “Another object is to provide a blowout preventer of the kind described, which will be composed to a minimum number of parts of simple and rugged construction.” The application’s basic patent was granted on January 12, 1926, U.S. patent no. 1,569,247.

By December 1931, Abercrombie patented an improved blowout preventer (patent No. 1,834,922, reissued in 1933). That design set a new standard for safe drilling during the Oklahoma City oilfield boom and other dangerously pressurized fields (see World-Famous “Wild Mary Sudik”).

Engineering Landmark

The blowout preventer saved lives and quickly became an industry standard. An original Abercrombie and Cameron blowout preventer was displayed in the Smithsonian Institution for many years before returning to Cooper Cameron headquarters in Houston, where it was displayed in the lobby. Cameron International was acquired by Schlumberger in 2016.

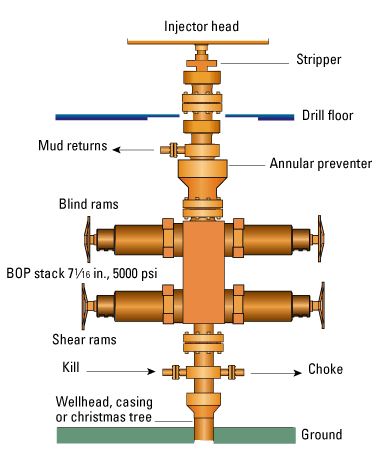

Modern blowout preventers include not only ram-types using steel rams to seal the borehole as in Abercrombie’s patents, but also annular BOPs (Granville Knox — 1952) and spherical BOPs (Ado Vujasinovic — 1972) stacked for redundancy and capable of withstanding pressures of 20,000 pounds per square inch.

This onshore BOP configuration from Schlumberger is typical for a well drilled with a hole size greater than four inches in diameter.

The early contributions of pioneers like James Abercrombie, Harry Cameron, and others made the search safer, more productive, and more sensitive to the environment.

In 2003, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers recognized the Cameron Ram-Type Blowout Preventer as a “Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark.”

Since the History and Heritage Program began in 1971, more than 235 landmarks have been designated as “historic mechanical engineering landmarks, heritage collections or heritage sites,” noted ASME during the July 2003 designation ceremony. “Each represents a progressive step in the evolution of mechanical engineering and its significance to society in general.”

Abercrombie, who died on January 7, 1975, received a total of 30 U.S. patents. His philanthropy, especially to Rice University and Texas Children’s Hospital, made Abercrombie one of Houston’s most respected citizens.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language (2012); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ending Oil Gushers – BOP.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/end-of-gushers. Last Updated: January 10, 2026. Original Published Date: February 1, 2010.