Oil Boom at Pithole Creek

Rise and fall of an infamous Pennsylvania boom town.

As the Civil War ended, oil discoveries at Pithole Creek in Pennsylvania created a headline-making boom town for the young U.S. petroleum industry. As wells drilled deeper into geological formations, the first gushers arrived — adding to “black gold” fever sweeping the country.

America’s oil production began in 1859 with Edwin L. Drake’s historic first commercial oil well drilled along a creek at Titusville. Drilled near natural oil seeps, his oilfield discovery at a depth of 69.5 feet led to a rush of exploration in the remote Allegheny River Valley.

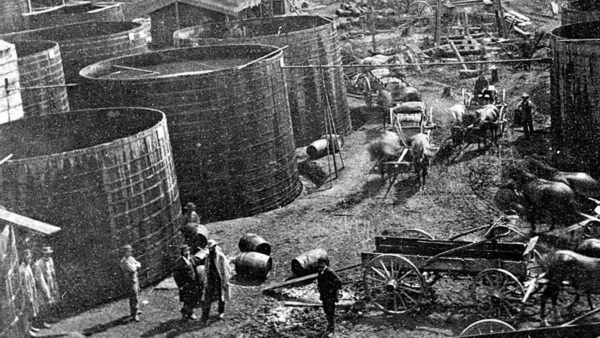

The new petroleum industry’s transportation infrastructure struggled as oil tanks crowded Pithole, Pennsylvania. In 1865, the first oil pipeline linked an oil well to a railroad station about five miles away. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

In 1864, businessman Ian Frazier found oil at Cherry Creek. After making a quick $250,000, Frazier looked for another opportunity in the hills and valleys providing oil to new Pittsburgh refineries making kerosene for lamps.

Frazier hired a diviner to search along Pithole Creek, which smelled like “sulfur and brimstone,” according to historian Douglas Wayne Houck. “He went to the creek and followed the diviner around until the forked twig dipped, pointing to a specific spot on the ground,” Houck noted in 2014.

Exploration techniques would improve, but with the science of petroleum geology still in the future, the oil industry (soon natural gas) already had begun drilling the first “dry holes.”

Pennsylvania Oil Geysers

Although Ian Frazier’s United States Oil Company’s steam powered, cable-tool derrick first drilled a dry hole, a second well erupted spectacularly on January 7, 1865, producing 650 barrels of oil a day. The Frazier well, proclaimed by Houck as the first U.S. oil gusher, brought a flood of drillers and speculators to Pithole Creek.

Two more wells erupted black geysers on January 17 and January 19, each flowing at about 800 barrels of oil a day (invention of a practical blowout preventer was still half a century away). United States Oil Company subdivided its property and began selling lots for $3,000 per half-acre plot.

The Titusville Herald proclaimed Pithole as having “probably the most productive wells in the oil region of Pennsylvania, Houck explained in his Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York.

Fortunes were being made and lost in the oil regions — see the cautionary tale of the Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny.”

As the news spread through Venango County, “everyone came to the Pithole area to try their luck,” noted one reporter. Many were Confederate and Union war veterans. And as more successful wells came in, about 3,000 teamsters rushed to Pithole to haul out the barrels of oil. It was hard to keep up.

Managed by the Drake Well Museum, the Pithole Visitors Center includes a diorama of the vanished town. Photo by Bruce Wells.

There were many reasons behind the Pithole oil boom, including a flood of paper money at the end of the Civil War. Many returning Union veterans had currency and were eager to invest — especially after reading newspaper articles about oil gushers and boom towns. Thousands of veterans also wanted jobs after long months on army pay.

By May 1865, the town was home to 57 hotels, many shops, and its own daily newspaper. It had the third busiest post office in Pennsylvania — handling 5,500 pieces of mail a day.

Pithole’s Lady Macbeth

In December 1865, Shakespearean tragedienne Miss Eloise Bridges appeared as Lady Macbeth in America’s first famously notorious oil boom town.

Bridges appeared at Murphy’s Theater, the biggest building in a town of more than 30,000 teamsters, coopers, lease-traders, roughnecks, and merchants. Three-stories high, the building had 1,100 seats, a 40-foot stage, an orchestra, and chandelier lighting by Tiffany.

Bridges was the acclaimed darling of the Pithole stage. Eight months after she departed for new engagements in Ohio, the oilfield at Pithole ran dry; the most famous U.S. boom town collapsed into empty streets and abandoned buildings.

Pennsylvania oil region visitors today walk the grass streets of the first oil boom ghost town.

First Oil Pipeline

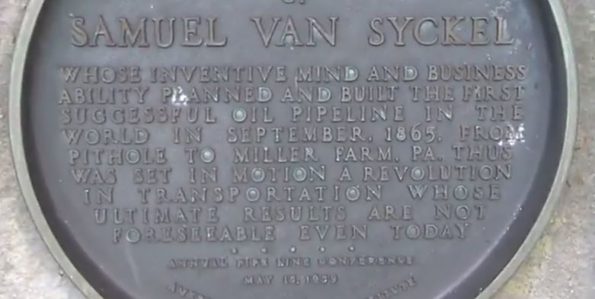

As Pithole oil tanks overflowed (and tank fires from accidents and lightening strikes increased), oil shipper Samuel Van Syckel conceived an infrastructure solution that became an engineering milestone.

In 1865, his newly formed Oil Transportation Association put into service a two-inch iron line linking the Frazier well to the Miller Farm Oil Creek Railroad Station, about five miles away.

“The day that the Van Syckel pipe-line began to run oil a revolution began in the business. After the Drake well it is the most important event in the history of the Oil Regions,” declared Ida Tarbell about the technology in her 1904 book, History of the Standard Oil Company.

Visitors walk the grassy paths of Pithole’s former streets and see artifacts, including antique steam boilers. Volunteers “mow the streets.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

With 15-foot welded joints and three 10-horsepower Reed and Cogswell steam pumps, the pipeline transported 80 barrels of oil per hour — the equivalent of 300 teamster wagons working for 10 hours. Convinced their livelihood was threatened, teamsters attempted to sabotage the oil pipeline until armed guards intervened.

Unfortunately for Van Syckel, Pithole oil storage tanks continued to catch fire even as the Frazier well production began to decline. Other wells were beginning to run dry when in 1866, fires spread out of control and burned 30 buildings, 30 oil wells and 20,000 barrels of oil.

“Pithole’s days were numbered,” concluded historian Houck about the fire, which was documented by early oilfield photographer John H. Mather. “Buildings were taken down and carted off. A few people hung around until 1867.”

The American Petroleum Institute in 1959 dedicated a plaque on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum as part of the U.S. oil centennial.

From beginning to end, America’s famous oil boom town had lasted about 500 days. Pithole was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 20, 1973.

A visitors’ center added in 1975 has been maintained by the Drake Well Museum. The center contains exhibits, including a scale model of the city at its peak and a small theater. Volunteers “mow the streets” on the hillside so that tourists can stroll where the petroleum boom town once flourished.

Among the Pennsylvania oil region’s earliest — and most infamous — investors was the actor John Wilkes Booth (see the Dramatic Oil Company).

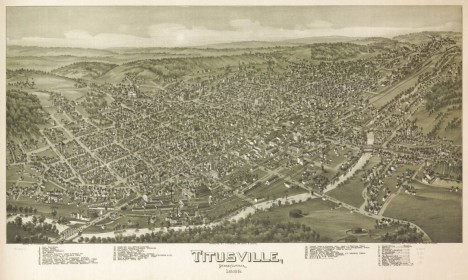

Oil Town Aero Views

During the late 19th century, “bird’s-eye views” became a widely popular way to map U.S. cities and towns. Cartographer Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created many of the best panoramic maps that he also called “aero views.”

The wealthy Pennsylvania oil regions attracted the attention of Fowler, who in 1885 moved his family to Morrisville, where he worked for the next 25 years.

Fowler drew maps of Titusville, Oil City, and many petroleum-related boom towns in West Virginia, Ohio — and Texas, where he created dozens of views of cities from 1890 to 1891.

But by far, most of the Fowler maps feature Pennsylvania cities between 1872 and 1922. There are 250 examples of his work in the collection of the Library of Congress. Learn more in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York (2014); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny

(2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Boom at Pithole Creek.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/pithole-creek/. Last Updated: November 19, 2024. Original Published Date: March 15, 2014.