by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Boom and bust of an obscure mid-continent petroleum company began in 1917.

The International Petroleum Register noted formation of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company as a Delaware corporation in 1917. With capitalization of $5 million in common stock authorized and more than $734,000 issued, the company obtained leases in Muskogee, Tulsa, Rogers, and Okmulgee counties in Oklahoma, and in Allen County, Kansas.

Major north Texas oilfield discoveries in Electra (1911) and Ranger (1917) attracted petroleum companies to the mid-continent. As oil demand soared during World War I, hundreds of new exploration and productions companies formed — and sought investors. Most of these companies would not survive.

By 1919, Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining’s lease ownership had expanded to 10,313 acres with an additional 815 acres from its acquisition of Tulsa Union Oil Company. About this time, all of the company’s petroleum production was sold to Prairie Oil and Gas Company.

Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining meanwhile continued drilling for oil in Coffee County, Kansas, and elsewhere, and the company’s estimated production reached 10,000 barrels of oil each month — a promising development for investors. The financial magazine United States Investor added a positive endorsement in May 1920 after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining reported production of 27,000 barrels of oil worth $65,000.

“It appears that this company is further along the road to development that a great many of the new oil companies, though whether its shares at the present offering price of $2.50 on the basis of a $1 par represent an extravagant price, cannot be told until further developments have occurred,” United States Investor reported.

However, six months later, the company’s shares were selling for less than 14 cents. Records of what went wrong are obscure. There are references to a convoluted business venture with another oil company. The deal was orchestrated by New York financier Mrs. Ada M. Barr after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining had failed in January 1921.The next month, after being put in the hands of a receiver, the company’s assets were sold for $87,400.

The buyer was Mrs. Barr, who soon would be enveloped in controversy and litigation of her own.

Acorn Petroleum Corporation, represented by Mrs. Barr, offered bonds in the amount of $150,000 of Acorn Petroleum Corporation on the basis of $250 in bonds for each $1,000 of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining stock held.

“The new company is operating the properties and has twenty-three producing wells, giving about ninety barrels of oil a day. The present low price for oil does not enable the company to earn sufficient income to pay interest on its bonds,” United States Investor noted. “Mrs. A.M. Barr, who arranged the financing of the new company, says that as soon as oil advances to a price that will permit, accrued interest on the bonds and dividends on the stock will be paid.”

But they weren’t.

By March 1923, investor Lewis H. Corbit filed a petition on behalf of a large number of local purchasers of stocks in the Acorn Petroleum Corporation of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The petition in the United States District court sought to determine the value of the local holdings, which represent an investment of approximately $100,000.

According to records, “In his complaint, asking for an investigation, Corbit alleges a stock, fraud in which $ 500,000 is involved. Certificates of shares held here were sold by a Mrs. A. M. Barr, it is disclosed in the petition.”

Further financial records and other details about Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company, Acorn Petroleum Corporation, and Mrs. Ada M. Barr can be research through the Library of Congress’ online Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

___________________

The stories of exploration and production (E&P) companies joining U.S. petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Somerset, Texas, was a quiet farming community about 15 miles from San Antonio on the Artesian Belt Railroad in 1913 when one of the town founders, Carl Kurz, discovered oil while drilling for water. The same thing had happened at Corsicana in 1894, bringing the first Texas oil boom.

The Somerset oilfield, which would extend south of Pleasanton, became known as “the largest known shallow field in the world at that time.” It joined other Texas discoveries making headlines since the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, almost 2,000 miles from Somerset, a group businessmen formed New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate, one of many companies to explore for oil southwest of San Antonio. Part of their incentive might have been a well owned by W.C. Steubing near the Somerset field.

Drilling the exploratory well with a rotary rig began on September 30, 1918, two miles southeast of Somerset. But three months and 1,688 feet deep later, Steubing’s well, the Sarah Smith No. 1, well proved to be an expensive “dry hole.” The New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate incorporated in Massachusetts with capitalization of $1 million and 200,000 shares of its stock with a nominal par value of $5.

“It is announced by Judge M.L. Barr, of Springfield, Mass., who recently arrived here to direct the oil operations of the New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate in the Somerset field, adjacent to San Antonio, that the company will proceed immediately to drill 100 wells on its leases,” noted Oil Paint and Drug Reporter in April 18, 1921.

The syndicate’s holdings included 330 acres from Glasscock Leasing Company, Clover Leaf Oil Company and others, the publication reported. Some 100 acres were leased near Fort Stockton and 30,000 acres of leases signed in Llano and Mason counties.

Back in Northampton, Massachusetts, more than 75 percent of shareholders were present personally or by proxy to elect their board of trustees for the New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate: Frederick L. Haskins, Thomas Brooks, and James E. Ryan.

The Petroleum Age trade publication added that syndicate trustee Frederick L. Haskins, “has taken over a considerable acreage in Somerset, and has announced that in addition to developing the shallow oil, a deep test will be started as soon as a contract can be made.”

At the time, the Somerset oilfield had nearly 300 shallow wells producing an aggregate of about 2,500 barrels of high-gravity crude oil daily.

But in January 1922, the United States Investor report the likely financial demise of the New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate. “We have seen nothing lately on this company and believe that very little market exists for the stock, as is the case of so many companies which have arisen within a year or two,” the business editors proclaimed.

Although New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate began rigging up to drill the Sarah Smith No. 2 well near the original W.C. Steubing well site, progress was slow. The Oil Weekly For several months, tracked the well’s status, but apparently nothing happened beyond erecting the drilling derrick.

The Texas Railroad Commission might have historical information about New England-Texas Oil Refining Syndicate. Another potential source is the Massachusetts Corporations Division.

———–

The stories of exploration companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2021 AOGHS.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2019 | Petroleum Companies

1917 oil discovery brings new exploration companies, drillers, speculators, and bankruptcies.

Ranger Extension Oil & Gas Company got its start thanks to the “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery of October 1917 at Electra, Texas. When a wildcat well on the McCleskey farm produced 1,200 barrels of oil in a single day, newspaper stories worldwide excited interest in the region’s oil riches, encouraging highly speculative ventures.

After the McCleskey No. 1 well found oil ay a depth of 3,432 feet, “development progressed rapidly, resulting in the extension of the Ranger field over several square miles of territory,” according to Contributions To Economic Geology (1922, Part II.) Ranger’s population soon grew from less than 1,000 people to more than 30,000 people.

Meanwhile, in Roanoke, Virginia, a group of entrepreneurs registered a new oil exploration company, Ranger Extension Oil & Gas Company, on September 13, 1919. The company secured a permit to do business in Texas and established headquarters in Sweetwater. By July 1920, leases had been acquired drilling begun at two wells, the No. 1 Woodrum in Nolan County, and the No. 2 Renner about 200 miles north in another booming region, the northwest Burkburnett oilfield.

Drilling with cable-tool technologies, the No. 1 Woodrum’s well bore soon “sanded in” at 780 feet deep, requiring a clean out. Operations were suspended and attention shifted to the No. 2 Renner. This exploratory well well fared better and was reported to be drilling beyond 1,500 feet by October 1920.

However, drilling deeper was not cheap, and from October until Christmas, Ranger Extension Oil & Gas suspended operations. For many newly formed exploration companies, drilling interruptions often were linked to a lack of funding, which often prompted increasingly vigorous stock sales. The company’s No. 2 Renner was given up as a “dry hole” and abandoned in February 1921.

The future of Ranger Extension Oil & Gas now depended on its remaining well, the No. 1 Woodrum in Nolan County. According to “The Oil Weekly,” drilling operations at the well restarted and had reached a depth of 2,485 feet by the end of April 1821. By mid-May, the well was reported to be 2,760 feet deep, reaching a depth of 2,835 feet by the end of the month.

Despite no sign of oil or natural gas, Ranger Extension Oil & Gas struggled along for months, drilling another 170 feet before giving up the No. 1 Woodrum well in November 1920. It was the end for the Roanoke, Virginia, entrepreneurs — and their stockholders’ investments. The company joined hundreds of other failed petroleum exploration ventures of the time, leaving behind paper stock certificates instead of dividends.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2020 AOGHS.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 25, 2019 | Petroleum Companies

Salt wells, oil wells, and salted wells bring excitement & controversy to western New York in 1890s.

Oil ruined saltwater wells long before petroleum became a profitable commodity. Then in August 1859, “Colonel” Edwin Drake drilled specifically for oil, found it in Titusville, Pennsylvania, and the U.S. petroleum industry was born.

Crude oil, whether retrieved by a spring-pole or cable-tool derrick, could be refined into the new wonder of illumination, kerosene. While drilling for salt brine remained a viable proposition, the new oil business brought spectacular tales of enormous wealth for a lucky few.

By 1878, Vacuum Oil Company (the future Mobil Oil) came looking for oil and natural gas in western New York’s oddly-named Wyoming County. Near the village of Bliss, drillers hit a 70-foot-thick bed of rock salt instead of petroleum. Vacuum Oil wasn’t in the brine business and promptly sold its interest to Wyoming Valley Salt Company. Other salt ventures followed, bringing Bliss new prosperity. Oil exploration companies moved on.

E.J. Wheeler and T.W. Lawrence – described as “two wide-awake business men of Bliss” – joined with prominent local insurance man, Norman R. Howes, to incorporate Bliss Salt & Oil Company in 1892. Stock sales would support drilling for salt, but striking oil or natural gas would be even better. In March 1892, capital stock was authorized at $4,000. “The company has over 3,000 acres of land leased and the shareholders expect to receive a good income from their investment,” reported the Wyoming County Times.

Bliss Salt & Oil Company’s first well was drilled on Stephen Bliss’ farm between Wiscoy Creek and the Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh railroad tracks. The company hired F.J. “Fitch” Adams as driller. He was a 14-year veteran of Pennsylvania’s giant Bradford oilfield, 50 miles to the south. At depth of 635 feet, Adams drilled into natural gas, but continued deeper using the gas to fuel the rig’s 25-horsepower boiler.

The company reported to investors, “Salt will no doubt be reached at about 2,500 feet and as we have an abundance of water and a good supply of gas for fuel, this will be one of the best locations for salt plants in America.” Drilling went on to a total depth of 2,956 feet, passing through a second gas sand layer (100 feet thick) on the way to becoming the deepest salt well in Eagle Township.

The presence of natural gas excited shareholders, who held a vote in August to increase capital stock to $6,000. Bliss Salt & Oil announced it was “Going After Gas.”

In April 1893, the company’s second well discovered natural gas at less than 600 feet deep. The Wyoming County Times featured “Booming Bliss” and declared, “A natural gas expert from Buffalo has advanced the opinion that this well will furnish 170,000 cubic feet of gas every twenty-four hours, and that the supply will last for years.”

The news drew Standard Oil Company’s attention. Agents were rumored to be scouting the area. Driller “Fitch” Adams was cited in the Times as believing the wells were “in the gas belt” and that the supply would be permanent. “He backs his opinion by buying stock….A number of experts have given their opinion that the supply is inexhaustible,” the newspaper added.

Bliss Salt & Oil secured a boiler and steam-engine and prepared to drill a third well; but by August, U.S. financial markets were deep into the Panic of 1893 (a harbinger of the Great Depression). Oil Well Supply Company sued both Fitch Adams and Bliss Salt & Oil Company to recover unpaid debts and won.

But then an unexpected show of oil at Bliss Salt & Oil No. 2 well convinced Standard Oil Company agents to make their move. The Times reported, “That was enough for them. They immediately wanted all of the remaining unissued stock and would pay cash for it.” In a quickly engineered takeover, Standard Oil bought out Bliss Salt & Oil shareholders.

However, subsequent Standard Oil exploration efforts suggested the No. 2 oil well discovery was a scam. It was reported the oil was likely poured from a can into the well’s borehole to fool oil scouts. During the gold rush, when crooked miners planted nuggets in worthless mines to fool investors, it was called, “salting the mine.” The local newspaper defended its readership and excoriated the Standard Oil Company.

Amid the controversy, Bliss Salt & Oil Company elected a new board of directors in March 1894. Investors meanwhile read a litany of corporate skulduggery in competing newspapers, including one in nearby Arcade, where the Wyoming County Herald noted:

“Left His Creditors – Norman R. Howes, A Prominent Citizen of Bliss, Absconds. – Becoming Involved in Financial Matters He Leaves Everything behind. – His Defalcations Aggregate, a Large Amount – Attachments on His Goods.”

For the next few years, the absent Howes was repeatedly and unsuccessfully summoned by the court. On May 10, 1895, “in pursuance of a judgment and decree of foreclosure and sale,” the remaining assets of Bliss Salt & Oil Company were auctioned in a sheriff’s sale by direction of the court.

The Wyoming County Times opined, “The truth of the matter seems to be that Mr. Howes became involved in business enterprises which have proven unrenumerative to save himself from what he had already put in them, borrowed money in hopes that business would soon revive and that as a consequence he would be able to retrieve that which he had lost.”

Learn more petroleum history of the Empire State by visiting the Pioneer Oil Museum of New York in Bolivar, Allegany County.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2019 Bruce A. Wells.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 20, 2017 | Petroleum Companies

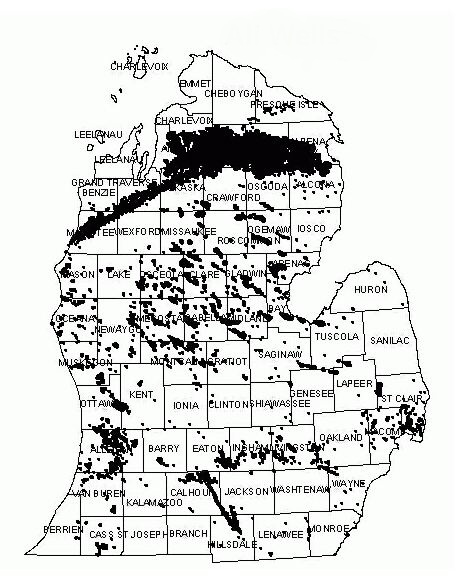

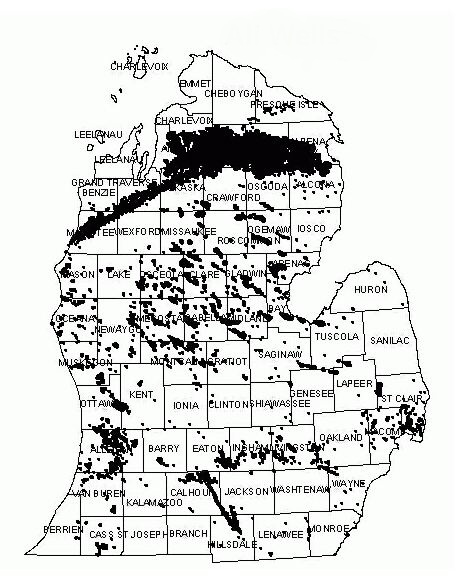

Years of unsuccessful pursuit of oil in Michigan led Petroleum Magazine to give up on the state’s potential by 1920. “Oil Hunt In Michigan Is Hopeless – Oil projects in Michigan are but dreams which fail to materialize, in the opinion of those connected with the state geological survey, and that conclusion is base on its scientific research,” the trade magazine explained. Then, the 1928 discovery of the Mt. Pleasant oilfield suddenly enabled Michigan to become a significant oil producer – and attract new exploration companies. More oilfields would be discovered, including one in 1957 almost 30 miles long.

According to the Clarke Historical Library of Central Michigan University: Mt. Pleasant became a hub of Michigan petroleum activity, first as an accident of geology and later as a convenience of geography. The community lies close to the geographical center of the “mitten”, thus located equal distance from anywhere in the Lower Peninsula. Primary oil and gas explorationists, petroleum supply and service companies, geologists (and later geophysicists), drilling contractors all headquartered in Mt. Pleasant.

Similar to earlier oil booms in Texas, the 1928 Michigan oil well attracted new and often inexperienced companies. Among those seeking Michigan’s oil riches was Charles Van Keuren, who in 1933 established the Morris-Van Keuren Oil and Gas Syndicate. The 1902 graduate of Michigan University and former member of the Michigan House of Representatives had earlier been a partner in a Detroit securities investment firm.

Van Keuren’s syndicate spudded its first well on November 14, 1933, in Vernon Township of Isabella County on a 340-acre lease near the Ann Arbor Railroad. A cable-tool rig reached a total depth of 3,750 feet and the well was completed April 17, 1934, producing an “initial flow of 130 barrels per hour.” Three days later, the Clare Sentinel newspaper reported the Bowman Heirs No. 1 well was producing 3,000 barrels a day. Morris-Van Keuren Oil and Gas Syndicate planned three additional wells nearby to tap into the prospect.

Michigan oil and natural gas fields.

However, the syndicate’s Bowman Heirs No. 2 well proved to be a dry hole at 3,788 feet deep. When two additional wells left no indications of production, exploration efforts moved to the challenges of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Intermittently drilled since 1903, the “U.P” had never produced commercial quantities of oil.

“Recent rumors of a large ‘play’ to test the oil possibilities of the contact area of Michigan’s sedimentary and outcrop area in the upper peninsula took substantial form this week when it was announced that Charles Van Keuren, oil operator of this city, has leased lands of the Hiawatha Sportsmen’s club for oil prospecting,” noted the Republican-News and St. Ignace Enterprise on May 21, 1936.

The newspaper reported the syndicate had leased tracts comprising more than 26,000 acres covering most of Garfield township, Mackinac county, and extending into Pentland township in Luce county.

However, a 1937 lawsuit alleging “fraud in the sale of certain syndicate certificates” delayed drilling operations. The syndicate’s Hiawatha Club No. 1 well, drilled between August 15, 1936 and June 9, 1937, proved to be a dry hole at 1,500 feet. The well had reportedly “showed oil saturation in the Trenton and underlying formations, but did not develop into commercial production.”

Undeterred, the company soon began to drill a followup well. By August of 1938, the Detroit Free Press noted, “After a series of arduous labors, including the building of a road through virgin forest and swamp land and the clearing of a site in ‘cutover,’ Charles Van Keuren’s north land explorative campaign on the 12,000-acre Hiawatha Club tract in Mackinac County of the Upper Peninsula, is in the active drilling state.”

The new well was in Section 17, Township 44 North, Range 8 West. “The production possibilities are thought to be somewhat like those of the Texas Gulf Coast field, where similar geological conditions obtain,” one newspaper proclaimed. “The development of commercial production would substantially advance the expectancy of deep drilling to these stratas along the ‘highs’ now producing in the central part of the State.”

Two months later, the Escanaba Daily Press reported, “Oil Outlook Is Favorable – Trace Of Petroleum Is Found In Well In Mackinac County” and “Indications in Garfield township have proved so good that, in case the first Van Keuren well does not prove productive, others are likely to be drilled in the adjacent area.”

Despite the optimism, Morris-Van Keuren Oil and Gas Syndicate, like many to follow, did not find oil in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. In 1939, the company undertook exchanges of Syndicate stock to support continued operations, but apparently to no avail. The Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities records Morris-Van Keuren Oil and Gas Syndicate No. 1 as dissolved on September 1, 1943. No commercial quantities of oil have ever been found on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

The largest Michigan oil and natural gas field was discovered in January 1957 on the dairy farm of Ferne Houseknecht. Her first oil well revealed Michigan’s golden gulch of oil that proved to be 29 miles long.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.