by Bruce Wells | Apr 6, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

Oil from the giant El Dorado oilfield was often featured in petroleum industry news as America prepared to enter World War I in April 1917. The mid-continent field, discovered two years earlier east of Wichita, had made headlines and launched a Kansas oil boom.

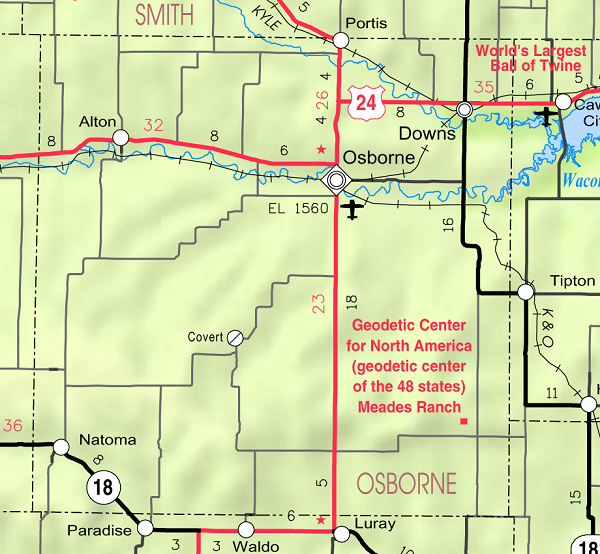

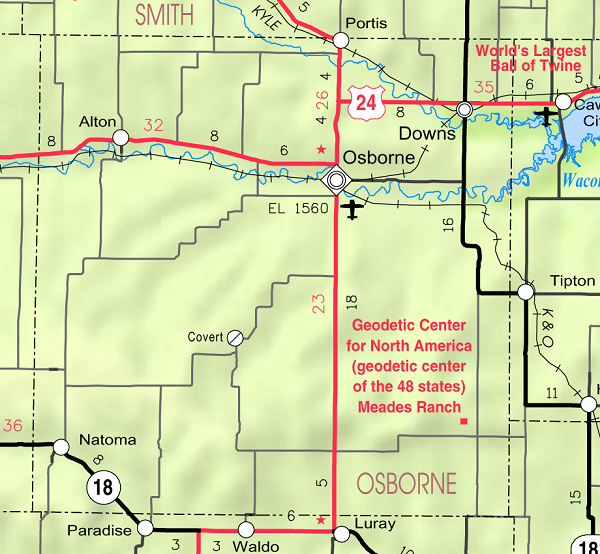

More than 200 miles to the northwest, the Delhi Oil Company would soon bet its fortunes on a wildcat oil well in Osborne County – and lose. In a chronology not unlike many small, community-based oil speculations, Delhi Oil began by seeking investors to fund its exploratory drilling.

The venture was started by Isaac M. Mahin, a state senator, and F.W. Mahin, both lawyers who owned the North Kansas Land & Loan Company in Smith Center. In November 1917, the Topeka Daily Capital reported the two men and other businessmen had “proposed to enter the oil hunting industry” by incorporating the Delhi Oil Company “with a capital stock of $60,000, all of which will be expended in drilling.”

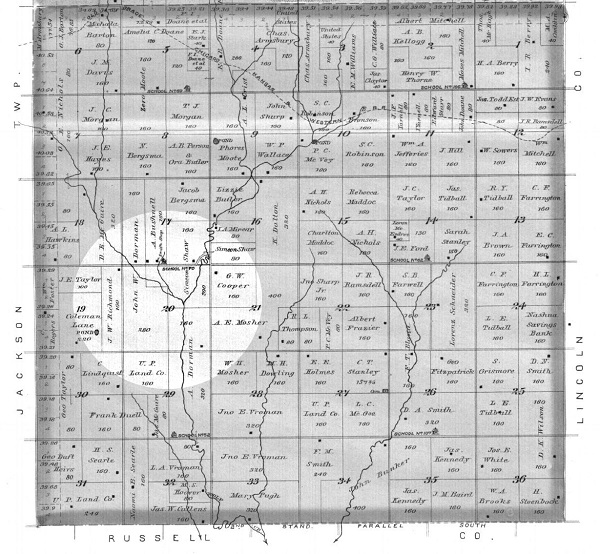

Delhi Oil secured leases in Smith and Osborne counties and by March 1918 had contracted for an 84-foot drilling rig. The company advertised in earnest for potential investors. “This is good news for the people of this county as it marks the beginning of actual oil development in Osborne County,” proclaimed one editorial ad in the Salina Evening Journal.

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.”

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.”

Although the first Delhi Oil well had yet to be spudded by early 1919, efforts to secure funds and investors continued. “Salina stands to benefit greatly by the development of the field,” stated one promotion. “Should gas be found, Salina’s fuel bill would be cut in half. Should a good oil field develop, Salina will become a refining and distributing center. And further, you have the assurance that every dollar you invest in this venture will be used in development, and also that your interest applies to the entire 5,320 acres.”

The newspaper’s praise continued: “This is to certify that we have thoroughly investigated the organization and plans of the Delhi Oil Company, are interested in their success and believe their stock to be a good, clean investment, one well worth your careful consideration.”

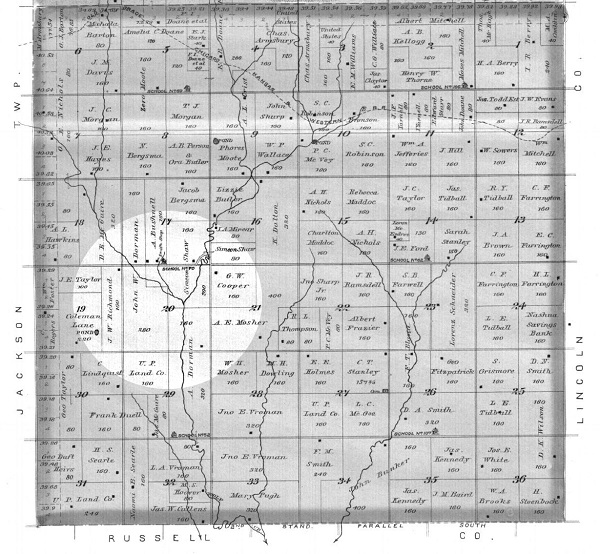

Sufficient working capital was finally secured and by May 1919, Delhi Oil’s wildcat rig was erected in Osborne County on the Dorman lease (Section 20 of Township 10 South, Range 11 West). It took eight months of drilling for the Dorman No. 1 well to reach 1,510 feet, ostensibly having seen a “show of oil” at just 500. Enthusiastic testimonials appeared in January 1921 newspapers:

“This news, together with the rumors that the company nine miles east of the Delhi lease is building oil tanks, has caused no little excitement among the people who are interested in the projects. There are real indications that a big field is about to be opened and the men who have their money invested are beginning to take heart over the outlook.”

“At this time they are drilling at a little more than 2,000 feet, in limestone,” reported the Western Kansas World in WaKeeney. “Delhi oil prospects are getting brighter and brighter each day. Sunday a large number of stock holders and others interested in the well were out watching the drill go down.”

Echoing a popular theme, the newspaper said the well “may mean untold wealth to Osborne County,” and on June 30, 1921, noted “the Delhi Oil Co. well near Luray is down 2,800 feet and it is said you can smell gas when you get near it.” But within four months, drilling at the Dorman No. 1 well was shut down at 2,930 feet. Securing working capital from investors remained a problem.

On April 13, 1922, the Salina Evening Journal reported Delhi Oil was “organizing in every town and township in Osborne county in an attempt to raise the necessary funds to complete the well on their leases. It is estimated that $20,000 will be needed to complete the project and one-half of that amount has already been raised, so that the big drive will have for its object the raising of the final $10,000.”

The newspaper added that “the money must be raised in the next two weeks, and if it is not forthcoming the well will be abandoned, as the company can no longer finance the drilling, although within 300 feet of what is believed to be a paying pool of oil.” Four days later the paper announced, “The Delhi Oil Company is making a county-wide drive in an endeavor to raise funds to complete their project within the next ten days.”

Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. At either depth, the hole was dry and shareholders lost their investment. Kansas Corporate Commission records show that Delhi Oil forfeited its charter to do business for failure to file required annual reports.

Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. At either depth, the hole was dry and shareholders lost their investment. Kansas Corporate Commission records show that Delhi Oil forfeited its charter to do business for failure to file required annual reports.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Jan 29, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

Home Oil & Development Company left better tracks in legal documents than in the oil patch.

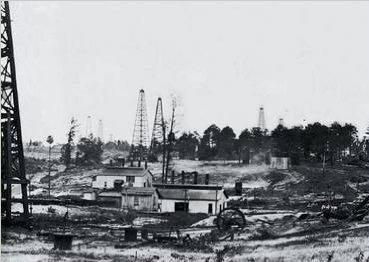

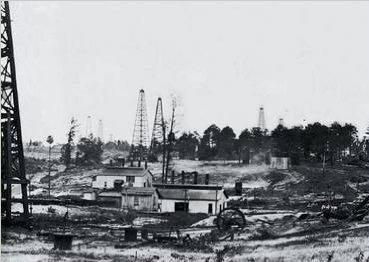

“For quickness of action in the formation of an oil company and the sale of stock the Home Oil and Development Company holds the record,” declared the The Lafayette Gazette on October 5, 1901. “This company was organized last Friday morning and by Saturday evening, the ground had been secured for drilling and a man sent to purchase the necessary machinery for drilling. Monday morning they were authorized to sell seventy thousand shares at 33 and 1/3 cents per share. This morning all the stock is sold. They will begin work next week.”

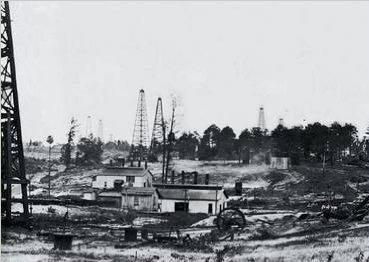

Despite being at the heart of Louisiana’s first oil boom, which between 1902 and 1908 produced virtually all of of the state’s oil, the company failed. Louisiana court records reveal Home Oil & Development ‘s demise in cases (no. 4374, no. 5021, no. 4733), and finally in the Louisiana Supreme Court (no. 15,468). A Louisiana company born to exploit the newly discovered Jennings oilfield, Home Oil & Development was insolvent within five years of its creation. Irate stockholders brought suit to recover some part of their lost investments.

“Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901 – 1946” by Kenny Arthur Franks and Paul F. Lambert includes images of Home Oil & Development Company.

Among the complainants were the Heywood brothers, whose discovery of the first Louisiana oil well in September 1901 had spawned a boom in drilling – and speculation.

By 1902, Home Oil & Development litigation in the Louisiana Supreme Court revealed that at the time of the bankruptcy, “The only asset owned the corporation consists of the amounts owing to it by its stockholders on the unpaid portion of the purchase price of the stock held and owned by them.”

With this rationale, those stockholders whose subscriptions were fully paid, “seek to obtain a personal judgement for the amount…against some few of its individual stockholders, claiming that they have not paid to it the full amount of their subscription to stock.”

The court did not agree, noting “the proper result should not be for individual creditors to institute individual actions inuring to their separate benefit and advantage.” The court concluded that the affairs of the corporation “should be placed in liquidation in the hands of some officer or officers acting in the interest of and for the benefit of all parties concerned.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Jan 20, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

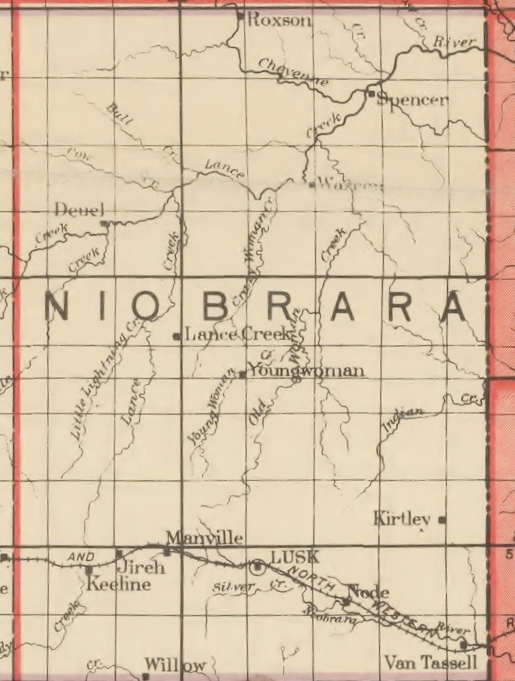

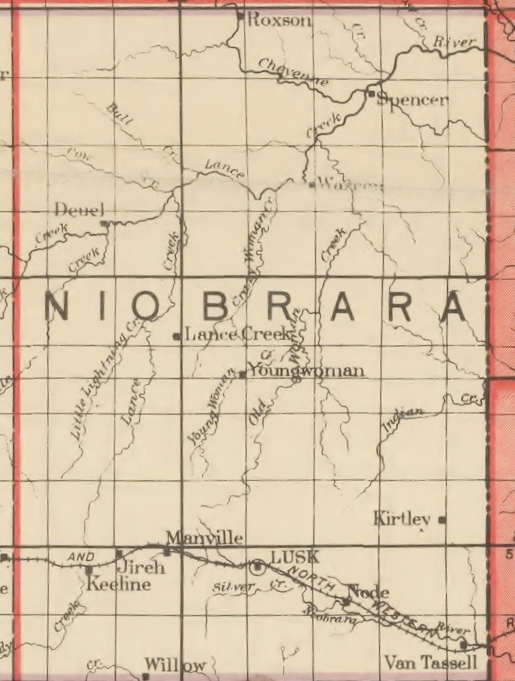

As early as September 24, 1917, the trade journal Oil, Paint, and Drug Reporter reported that Clark Producing & Refining Company would be drilling a well on the “Old Woman Creek dome, adjoining the Norbeck-Nicholson holdings,” about 35 miles north of Lusk,Wyoming.

As early as September 24, 1917, the trade journal Oil, Paint, and Drug Reporter reported that Clark Producing & Refining Company would be drilling a well on the “Old Woman Creek dome, adjoining the Norbeck-Nicholson holdings,” about 35 miles north of Lusk,Wyoming.

The journal added the company held “acreage to the amount of 5,560 acres, and has two additional drilling outfits in transit for work as soon as they arrive on the property.”

The first Wyoming oil wells had arrived in 1890 near ancient “tar springs” north of Casper. Although Clark Producing & Refining’s leases were to east, near the border with Nebraska, the company was enthusiastically endorsed by newspapers, trade journals, and in advertisements soliciting investors.

In Lead, South Dakota, a quarter-page ad in the Lead Daily Call proclaimed in bold print “a harvest of profit awaits the investor in the Clark Producing & Refining Co.” and described holdings of more than 6,000 acres “in the heart of the Old Woman Creek Dome in the North Lusk Oil Field.”

The ad also promoted the company’s leases adjoining a 1916 local sensation, the Norbeck-Nicholson well at Cow Gulch. With one Clark Producing & Refining well about to be spudded (begin drilling) and a second rig planned, potential investors were advised to buy stock at only 26 cents per share to insure “Quick Profits.”

Drilling began on the company’s first well on Old Woman Creek in the southwest of the northwest quarter of Section 10, Township 36 North, Range 62 West. This lease location, described in Public Land Survey System terms, can be viewed in Google Earth and similar applications.

To fire the steam boilers to begin “making hole,” teamsters for Clark Producing & Refining’s hauled fuel oil from the Mule Creek field, about 15 miles to the northeast. By January 1918, a company rig had reached 1,200 feet deep.

When the Lusk Stock Exchange opened in February, Clark Producing & Refining was the first local petroleum stock to be placed on sale (see also the “Curb Market” described in Consolidated Petroleum Company). Drilling on the “Old Woman” well would continue into April 1922 as the company looked for more lease opportunities.

“COW GULCH STILL ALIVE,” proclaimed the Lusk Standard of November 26, 1920. The Oil Distribution News also reported events, noting, “The Clark Producing & Refining Co., composed mainly of Lusk citizens, is making headway with a test of the Young Woman dome, material has been assembled, and gas piped from the so called ‘Cow Gulch’ well completed some time ago by Norbeck and Nicholson.”

Powered by gas-fired boilers, drilling of the “Young Woman” well began. But at 1,472 foot depth, water intrusion into the well bore ruined the attempt. Meanwhile, the “Old Woman” well reached 1,900 feet deep and found a “considerable showing” of natural gas.

Managing multiple operations consumed Clark Producing & Refining Company’s the company’s rigging, equipment and casing supplies without yielding oil. In March 1922, National Petroleum News noted the company’s slow progress at the “Old Woman,” but predicted drilling would begin again “as soon as road conditions to the region are improved.”

A month later, Clark Producing & Refining was the only company still drilling in the eastern part of the Lusk oilfield, the other exploration companies having chased oil strikes further west into the Lance Creek field.

The company decided to use a down-hole explosive to “shoot” the “Old Woman” well at 2,100 feet deep to stimulate oil production, but fracturing did not succeed. The well “reached a depth of 2,160 feet when shut down for the winter. It is now waiting for the roads to become passable so as to move in fuel oil from the Mule Creek field.” No reports followed to indicate drilling ever began again. Like many of its contemporary high-risk petroleum ventures, Clark Producing & Refining likely just ran out of money.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

by Bruce Wells | Jan 19, 2016 | Petroleum Companies

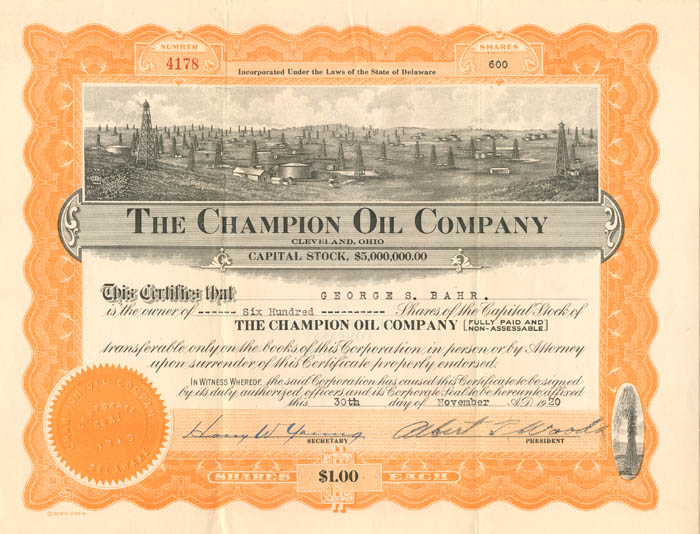

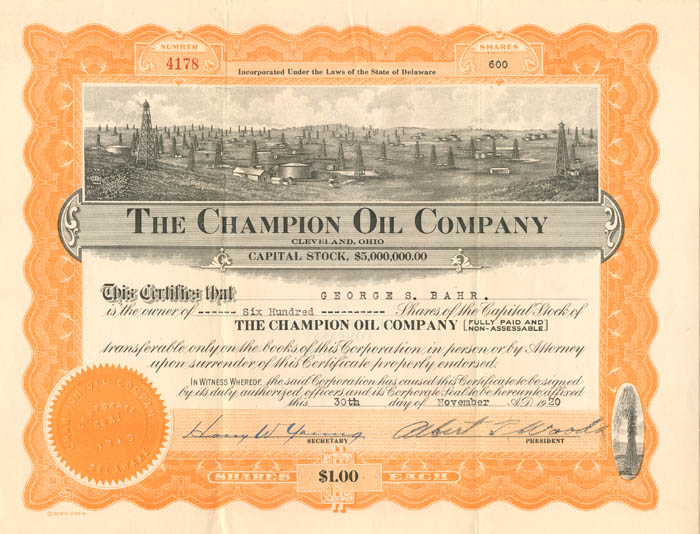

With hopeful prospects and properties in six petroleum-producing Oklahoma counties, Champion Oil Company began on October 25, 1919. The Muskogee-based company “engaged in the production of oil and the manufacture of casinghead gasoline.” Its balance sheet reflected more than $2.5 million in assets and the equivalent debt.

There were many exploration and production investment choices for investors seeking to cash in on the post-World War I Oklahoma oil booms. “For twenty-two years between 1900 and 1935 Oklahoma ranked first among the Mid-Continent states in oil production,” notes the Oklahoma Historical Society. “The state produced 906,012,375 barrels of oil worth approximately $5.28 billion.”

United States Investor proclaimed Champion Oil Company President Albert T. Woods as a highly regarded man of experience and ability. The magazine reported that Champion Oil had leased 2,000 acres of promising land in prolific Mid-Continent oilfields. The company’s stock sold for as much as $1.50 per share, with assurances that it would go to $2 a share.

Looking for investors to fund operations, the company peddled a prospectus promising 12 percent per year dividends. Sales were especially substantial in Cleveland and Syracuse, where salesmen earned a 15 percent commission.

Although the company apparently looked good to many investors, just two years later Poor’s Government & Municipal Supplement reported the company as “inactive at the present time.”

After stockholders had poured several hundred thousand dollars into the venture, Champion Oil Company was foreclosed upon and rendered bankrupt. U.S. Investor published a blistering indictment of Champion Oil and its president.

“Albert T Woods, the president and general manager, had shaken the dust of Muskogee and of Oklahoma from his feet, and had moved with his family to Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he set himself up as an independent oil operator, under the name of the Albert T. Woods Company,” the magazine noted.

With Champion Oil stockholders left with worthless paper, Woods made a brief effort to exploit the loss. He pitched an idea to exchange obsolete Champion Oil stocks for shares of the Revere Oil Company. This Revere Oil scheme is described in Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

According to the Commercial & Financial Chronicle of July 10, 1926, Champion Oil’s final curtain came when company shares were offered in lots of 12,000 shares for $5 (common) and 7,000 shares of preferred for $15.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.”

The newspaper also noted, “the Delhi Oil company which is composed of local men with headquarters in Osborne seeking to develop the resources of Osborne County, should have the support of every businessman and land owner in this community.” Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. At either depth, the hole was dry and shareholders lost their investment. Kansas Corporate Commission records show that Delhi Oil forfeited its charter to do business for failure to file required annual reports.

Somehow, Delhi Oil was able to drill its Dorman No. 1 well deeper, adding another 320 feet to a total depth (TD) of 3,250 feet, according to World Oil, Volume 33, 1924, or another 548 feet to a TD of 3,478 feet, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. At either depth, the hole was dry and shareholders lost their investment. Kansas Corporate Commission records show that Delhi Oil forfeited its charter to do business for failure to file required annual reports.

As early as September 24, 1917, the trade journal Oil, Paint, and Drug Reporter reported that Clark Producing & Refining Company would be drilling a well on the “Old Woman Creek dome, adjoining the Norbeck-Nicholson holdings,” about 35 miles north of Lusk,Wyoming.

As early as September 24, 1917, the trade journal Oil, Paint, and Drug Reporter reported that Clark Producing & Refining Company would be drilling a well on the “Old Woman Creek dome, adjoining the Norbeck-Nicholson holdings,” about 35 miles north of Lusk,Wyoming.