by Bruce Wells | Aug 20, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

The “Snake Hollow Gusher” brought Pittsburgh a $35 million natural gas drilling boom — and bust.

“Rarely, a community sees its pulse quicken with a get-rich-quick beat, feels the boom fever strike, suffers the chill of disillusion when the ‘El Dorado’ fades out and then recovers,” noted the Pittsburgh Press in 1934, decades after the excitement began.

“But this is what happened at the McKeesport gas field, scene of the Pittsburgh district’s biggest boom and loudest crash,” the newspaper added. McKeesport Gas Company was among the many petroleum company casualties.

Pennsylvania’s natural gas fields attracted investors to many ambitious drilling ventures, including McKeesport Gas Company.

Following the first U.S. oil discovery at Titusville, Pennsylvania, in late August 1859, natural gas development began in western Pennsylvania.

With new oilfields came discoveries of large volumes of gas suited for illumination, heating, and manufacturing. Natural gas began to be widely used after two brothers drilled into a giant, highly pressurized field on November 3, 1878.

The Haymaker brothers’ discovery brought the new energy resource to Pittsburgh factories and steel mills. By the late 1880s, Pittsburgh skies cleared for the first time in decades as mills and factories burned natural gas instead of coal.

Learn more about the once nationally famous Haymaker gas well of 1878 in Natural Gas is King in Pittsburgh.

Biggest Boom

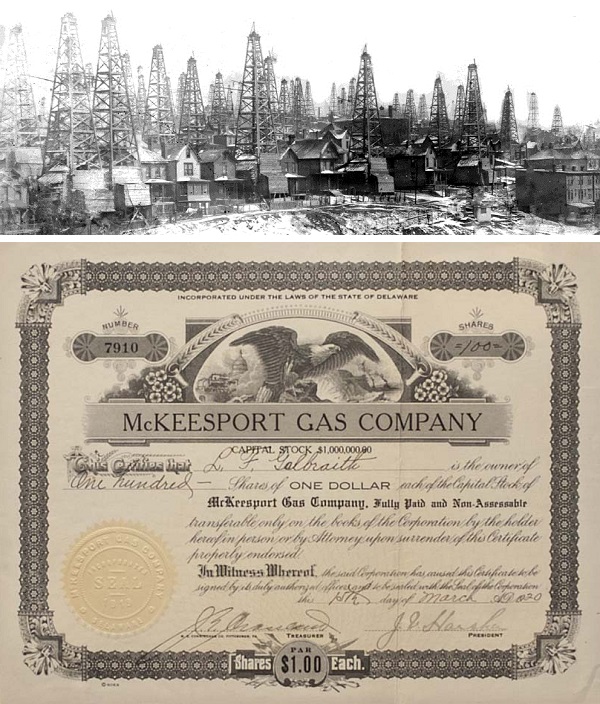

For investors in 1919, the region’s natural gas history seemed to be repeating itself. McKeesport Gas Company was one of about 300 petroleum companies that sprang up within six months of an August 30, 1919, discovery — a runaway natural gas well near McKeesport.

The “Snake Hollow Gusher” between the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers blew in at more than 60 million cubic feet of natural gas a day. The headline-making gas well, drilled by S.J. Brendel and David Foster, prompted a frenzy that saw $35 million dollars invested during the boom’s seven-month lifespan.

McKeesport Gas Company incorporated on December 5, 1919, and two weeks later enticed investors with advertisements in the Pittsburgh Press and the Gazette Times newspapers. “Over 500 Acres of Leases in the Heart of the McKeesport Gas Fields,” proclaimed one newspaper ad, offering stock at $1.25 a share.

“Many residents signed leases for drilling on their land,” noted another local reporter. “They bought and sold gas company stock on street corners and in barbershops transformed into brokerage houses in anticipation of fortunes to be made.”

Then the natural gas reserves ran out.

Loudest Crash

By the beginning of 1921, McKeesport’s natural gas production was falling in about 180 producing wells and new drilling resulted in about 440 unsuccessful wells — dry holes. The field would be reported as “the scene of the Pittsburgh district’s biggest boom and loudest crash.”

Of the estimated $35 million sunk into the nine square mile area of the boom, only about $3 million came out.

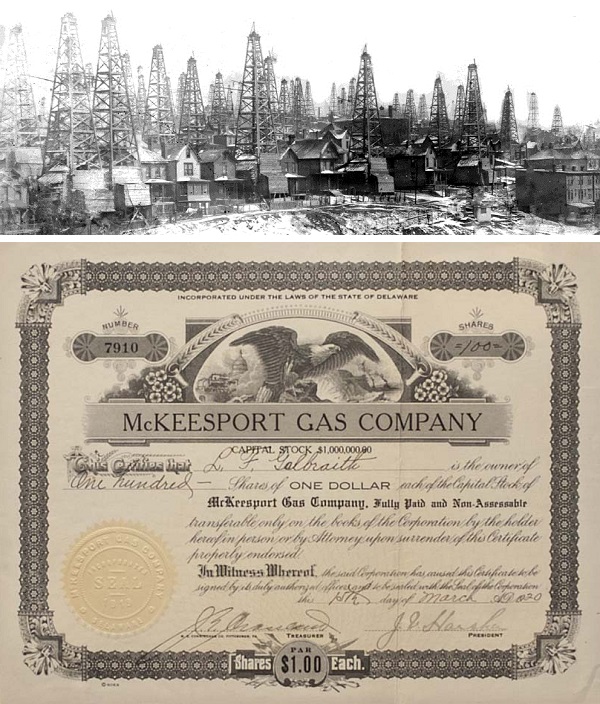

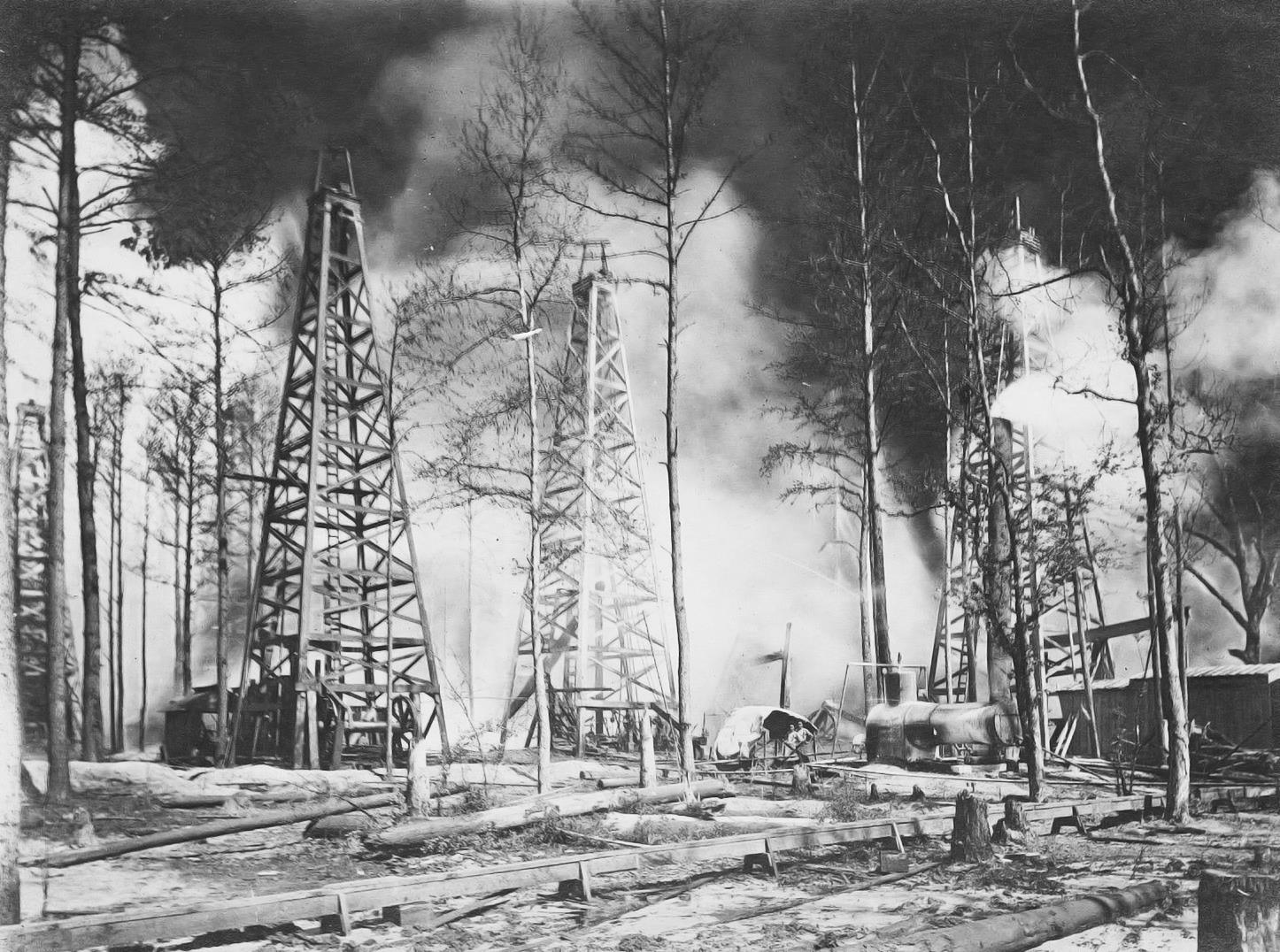

A detail from “McKeesport, Snake Hollow, Gas Belt,” a circa 1920 panoramic image by Hagerty & Griffey. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

A circa 1920 panoramic photograph at the Library of Congress captured the drilling boom at the McKeesport, Snake Hollow, Gas Belt, by Hagerty & Griffey.

McKeesport Gas Company likely drilled a few of the boom’s hundreds of dry holes, and with funds exhausted, disappeared into petroleum history. Fifteen years later, McKeesport Mayor George H. Lysle explained to a Pittsburgh newspaper reporter how the town survived the “seven-month wonder” natural gas boom:

“Other boom towns,” he said, “were built merely on the strength of the wealth that was to pour from their wells or mines. But McKeesport and vicinity was established before the boom came.”

When the drilling ended, Lysle added, “People still had their jobs in the mills and stores, the permanent population remained, and the natural resources of the district, except for gas, were still as great as ever. We were still a great industrial community.”

Advances in the science of petroleum geology and improved production technologies have brought surer results than the Snake Hollow Gusher. As early as 2010, the region’s gas boom — the Marcellus Shale — extended across western Pennsylvania into other Appalachian Basin states.

Because of the region’s history, McKeesport Gas Company stock certificates are considered collectible; the stories of other exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in the updated research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: McKeesport – Images of America: Pennsylvania (2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “McKeesport Gas Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/mckeesport-gas-company. Last Updated: August 21, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 1, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

The brief oilfield journey of a “staveless” wooden barrel maker.

The U.S. petroleum industry was barely a decade old and as oil discoveries spread from northwestern Pennsylvania’s first commercial well, efficiently transporting the resource became critical. In Brooklyn, New York, the Staveless Barrel and Tank Company organized. The company hoped to exploit a new patent for making barrels.

Capitalized in 1867 at $500,000 with 5,000 shares at $100 each, Staveless Barrel and Tank’s barrel-making process included, “application of scale-boards or veneers in layers, the direction of whose grain is crossed or diversified, and which are connected together, forming a material for the construction, lining, or covering of land and marine structures.” (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jun 11, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

When Edwin L. Drake drilled the first U.S. oil well in 1859 along a creek at Titusville, Pennsylvania, he transformed the landscape of the Allegheny River valley — and America’s energy future. The former railroad conductor’s discovery launched a new industry as investors and drillers rushed to cash in on the new resource for making kerosene for lamps.

Wallace Oil Company would be among the earliest U.S. petroleum companies, and the venture’s fate would presage the riskiness of America’s new exploration and production industry.

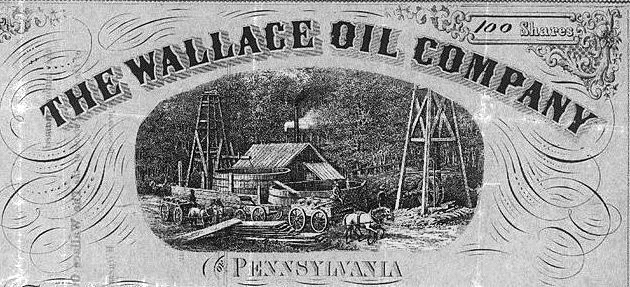

Grocery store owner John Wallace formed the Wallace Oil Company in 1865 to drill for “black gold.” Detail from Wallace Oil Company stock certificate.

The ensuing scramble fueled the nation’s first petroleum drilling boom. Newspapers reported discoveries on farms clustered in Northwestern Pennsylvania’s “oil region.”

Newly incorporated oil companies rushed to construct wooden derricks with steam-powered cable tools for “making hole.”

Drillers came to John Rynd’s farm at the junction of Oil Creek and Cherry Tree Run, the Blood farm to the north, and the widow McClintock farm to the south.

Pennsylvania Oil Fever

Operating a grocery store on the Rynd farm in 1859, Irish immigrant John Wallace witnessed the excitement firsthand. When the first of many wells found oil on the farm in 1861, derricks already crowded nearby hillsides. Four years later, the 24-year-old entrepreneur caught oil fever and incorporated Wallace Oil Company in 1865 with an office at 319 Walnut Street in Philadelphia.

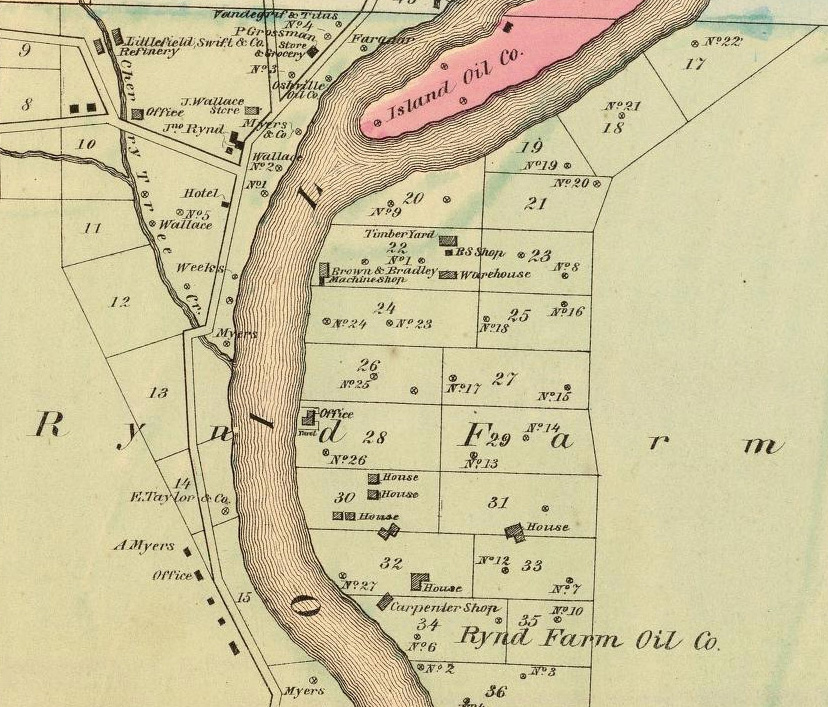

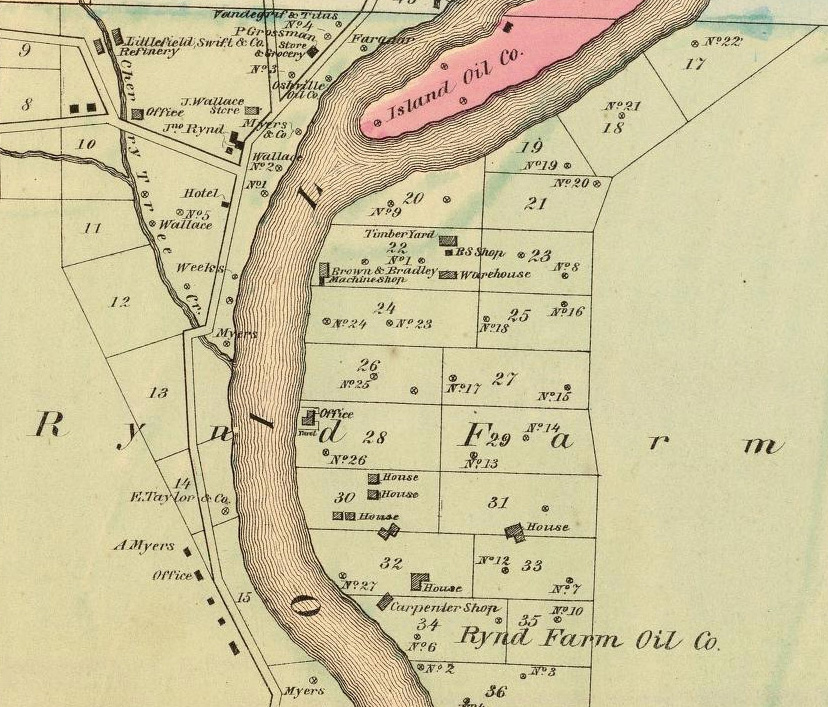

After witnessing the oil region’s drilling boom from his Rynd farm grocery store, John Wallace caught oil fever. “Oil Region of Pennsylvania,1865” map courtesy David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, F.W. Beers & Co.

With the science of petroleum geology in its infancy, “creekology” and oil seeps often were the only tools for finding promising locations to drill. Some exploration companies turned to dowsing (hazel or peach tree rods preferred) to find oil.

Wallace’s company sold stock certificates and acquired a 3/32 royalty interest in a 200-acre tract on the neighboring McClintock farm (previously owned by investors Curtiss, Haldeman, and Fawcett).

Although records offer no evidence of Wallace Oil Company actually drilling and completing a well, Wallace’s lease trading speculations, financed by his 3/32 royalty income, and energetic sales of stock, made the company money.

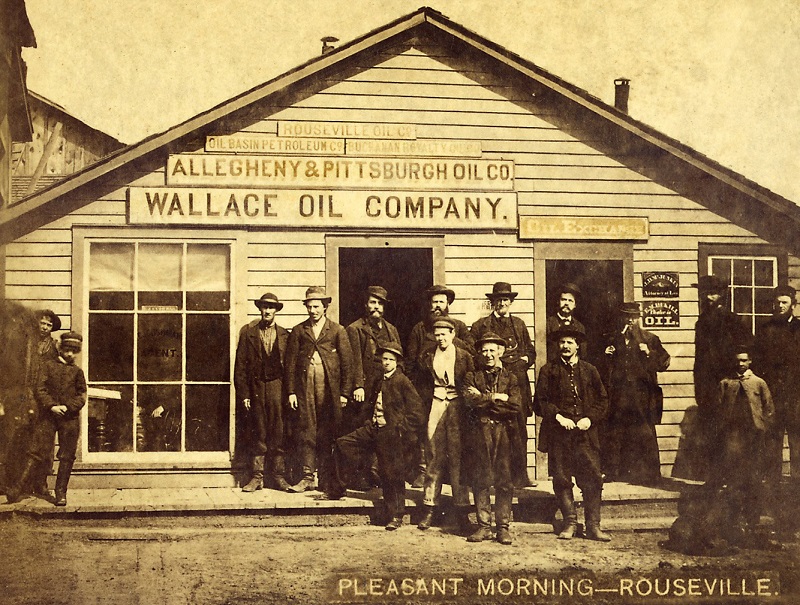

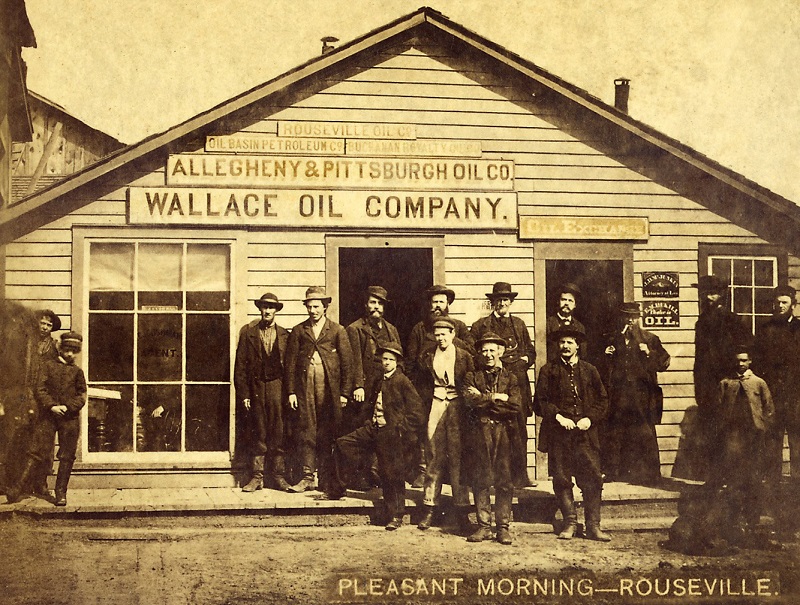

A circa 1875 building at Rouseville in the Pennsylvania oil region hosted an attorney, lease agents, a small oil exchange, and petroleum companies like Wallace Oil Company. Detail from stereograph “Pleasant morning – Rouseville,” courtesy Library of Congress.

Purchasers of Wallace’s stock stood to gain from both royalties and appreciation. The financial horizon looked promising. In 1865, a 42-gallon barrel of oil sold for $6.59 a barrel (nearly $100 in 2013 dollars).

Boom and Bust

As the gamble to find oil spread, Pithole Creek and other oilfield discoveries inspired more drilling — and speculation at oil exchanges in Titusville, Oil City, and elsewhere.

Those seeking petroleum riches in 1864 included John Wilkes Booth, whose Dramatic Oil Company drilled on a 3.5-acre lease on the Fuller farm.

By the end of 1869, Wallace Oil Company ‘s McClintock farm leases still produced an average of 200 barrels of oil daily from 32 wells. It took three more years before Wallace Oil Company paid its first and only dividend to investors, who received one cent per share in 1874. But by then, one industry publication noted, “oil had left the territory.”

The company dutifully paid the state an annual “Tax on Stock,” and in 1871 paid its first “Tax on Income.”

A circa 1875 Library of Congress stereograph of a small building includes signs for the “Wallace Oil Company,” the “Allegheny & Pittsburgh Oil Co.,” the “Oil Basin Petroleum Co.,” the “Buchanan Royalty Oil Co.,” and the “Rouseville Oil Co.”

Rouseville in 1861 had been the scene of a deadly oil well fire, one the earliest fatal conflagrations of the U.S. oil and natural gas industry.

By the early 1890s, Wallace Oil Company’s expanded oil-region holdings were reduced to the original 3/32 royalty from its McClintock property, which no longer produced commercial quantities of oil. Overproduction had drained profitability from the countryside.

In August 1895, American Investor reported Wallace Oil Company had lost its wells and property and could not even muster resources to pay legal fees associated with formal dissolution of the company. The grim assessment concluded, “The company is in a hopeless condition. The stock has no market value.”

Visit the Drake Well Museum and Park in Titusville.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Wallace Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/wallace-oil-company. Last Updated: June 11, 2024. Original Published Date: June 17, 2021.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 24, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

New companies rush to drill at Spindletop Hill in early 1900s.

When a geyser of oil erupted in 1901 on Spindletop Hill, near Beaumont, Texas, it launched the greatest oil boom in America — far exceeding the nation’s first commercial oil well in 1859.

Many new and inexperienced oil ventures were formed almost overnight, including Buffalo Oil Company. The Spindletop field produced 43 million barrels of oil in its first four years, helping to launch the modern petroleum industry.

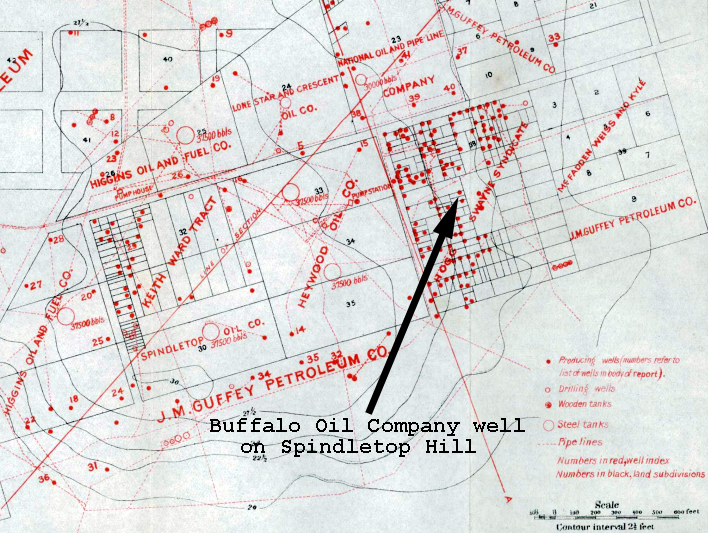

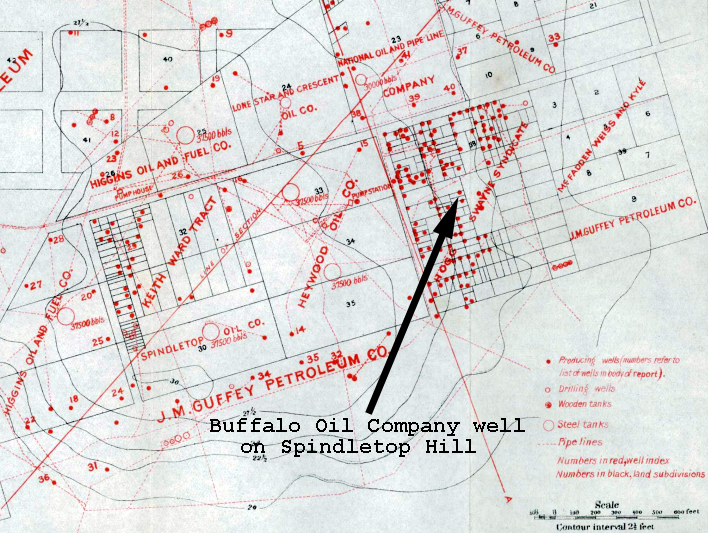

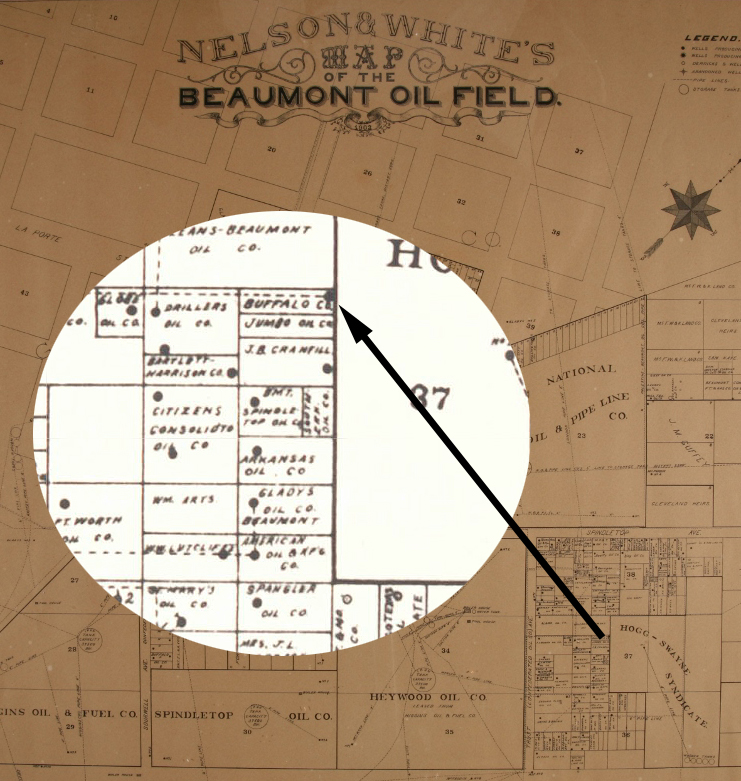

Among the 280 wells at Spindletop in 1902, Buffalo Oil completed a producing oil well at a depth of 960 feet on a lease of only 1/32 of an acre.

Buffalo Oil Company had quickly formed with $300,000 capitalization and stock listed with par value of 10 cents. Encouraged by the first well’s success, speculators invested in the company’s second. But by May 1902 the second Buffalo Oil well was “dry and abandoned” after reaching 1,400 feet deep.

As at least one expert noted at the time, the average life of flowing wells was short, “frequently but a few weeks and rarely more than a few months, with constantly diminishing output.”

Meanwhile, competing companies drove up the cost of drilling equipment and leases. Spindletop Hill was crowded with wooden derricks, oil storage tanks, and roughnecks.

Batson Oiflield

With signs of Spindletop production dropping, Buffalo Oil shifted operations to nearby Batson, where a 1903 well drilled by W.L. Douglas’ Paraffine Oil Company produced 600 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 790 feet. But the exploration company’s luck did not improve.

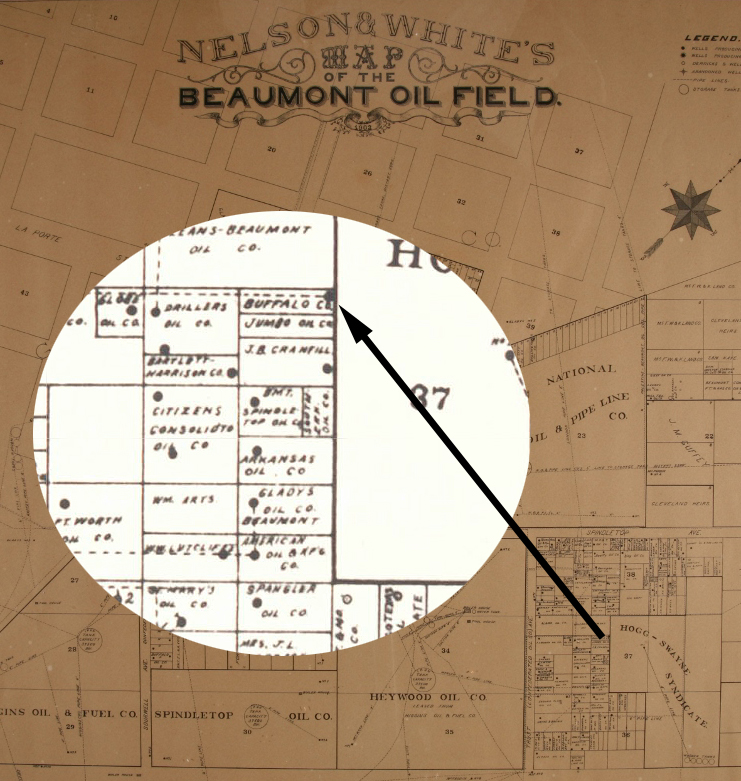

Map with detail showing Buffalo Oil Company lease among other drilling companies at Beaumont, Texas, home of a giant oilfield discovered in 1901.

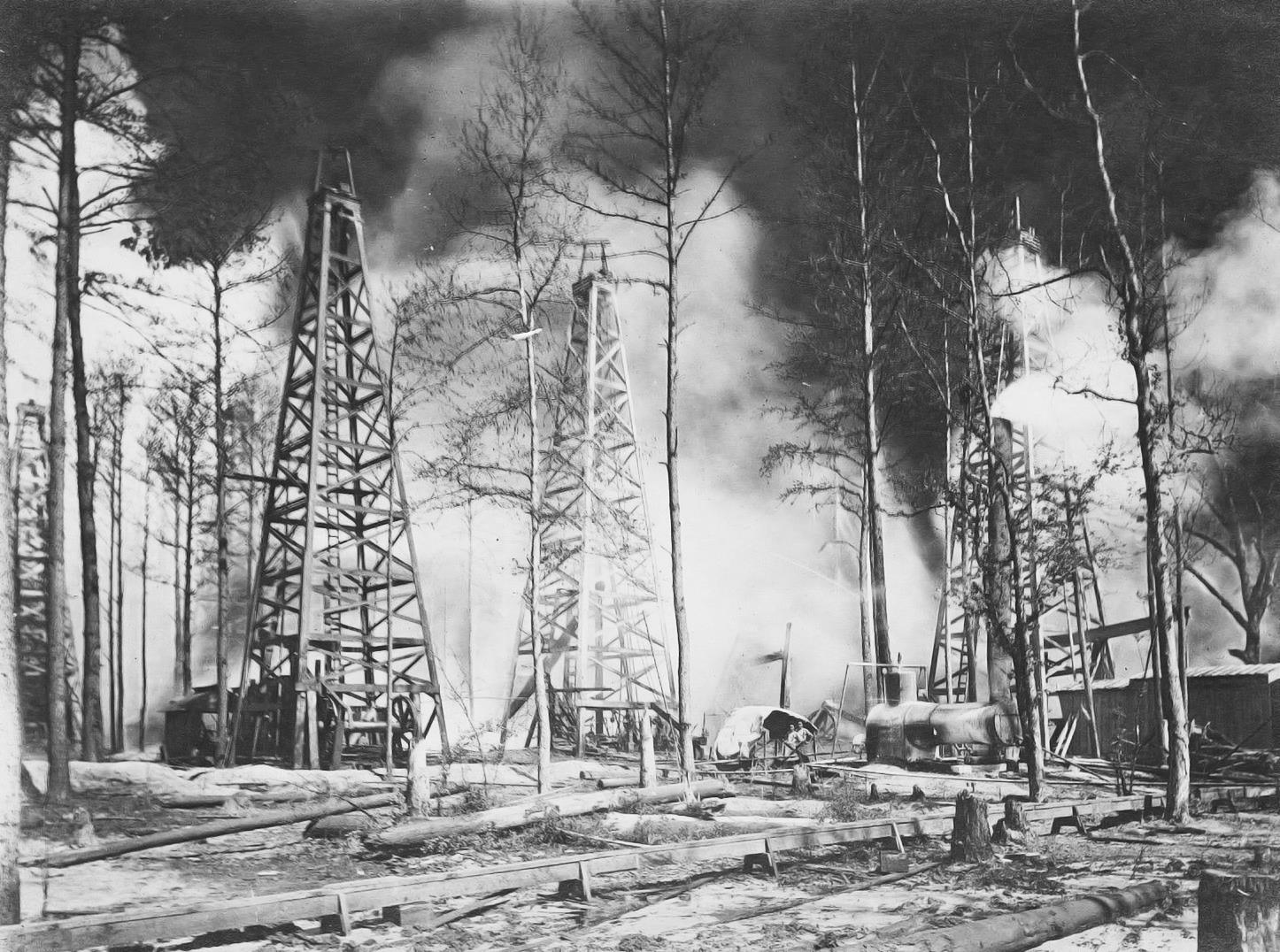

As the Batson field reached its peak monthly production of 2.6 million barrels of oil, a fire swept through the crowded oilfield.

“The fire burned furiously for several hours and though there were no fire appliances on the field, it is doubtless if equipment could have been used owing to the intense heat generated by the flames,” noted the Petroleum Review and Mining News.

Buffalo Oil Company’s well, derrick and equipment were completely destroyed.

Often caused by lightening strikes, oil tank fires were sometimes fought using cannons (learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires). After the Batson fire, the annual Buffalo Oil Company stockholder’s meeting took place in April 1904.

Fire engulfed the Batson oilfield in 1902, destroying the equipment and future of Buffalo Oil Company. Photo courtesy Traces of Texas.

“The company states that their recent investment at Batson so far has proved a serious loss to them, and the present outlook is very unfavorable,” reported the Petroleum Review and Mining News. But it got even worse.

Two weeks after the dire report to share owners, a second Batson fire destroyed another Buffalo Oil producing well and two 1,200-barrel storage tanks. Petroleum Review and Mining News concluded the fire “probably originated through an explosion in the pumping plant.”

The Batson oilfield would continue to produce for many years, but without Buffalo Oil Company. As late as 1993 the field yielded almost 200 barrels of oil a day, but Buffalo Oil was history without having paid a dividend.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Buffalo Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/buffalo-oil-company. Last Updated: October 31, 2023. Original Published Date: October 28, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 1, 2021 | Petroleum Companies

Boom and bust of an obscure mid-continent petroleum company began in 1917.

The International Petroleum Register noted formation of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company as a Delaware corporation in 1917. With capitalization of $5 million in common stock authorized and more than $734,000 issued, the company obtained leases in Muskogee, Tulsa, Rogers, and Okmulgee counties in Oklahoma, and in Allen County, Kansas.

Major north Texas oilfield discoveries in Electra (1911) and Ranger (1917) attracted petroleum companies to the mid-continent. As oil demand soared during World War I, hundreds of new exploration and productions companies formed — and sought investors. Most of these companies would not survive.

By 1919, Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining’s lease ownership had expanded to 10,313 acres with an additional 815 acres from its acquisition of Tulsa Union Oil Company. About this time, all of the company’s petroleum production was sold to Prairie Oil and Gas Company.

Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining meanwhile continued drilling for oil in Coffee County, Kansas, and elsewhere, and the company’s estimated production reached 10,000 barrels of oil each month — a promising development for investors. The financial magazine United States Investor added a positive endorsement in May 1920 after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining reported production of 27,000 barrels of oil worth $65,000.

“It appears that this company is further along the road to development that a great many of the new oil companies, though whether its shares at the present offering price of $2.50 on the basis of a $1 par represent an extravagant price, cannot be told until further developments have occurred,” United States Investor reported.

However, six months later, the company’s shares were selling for less than 14 cents. Records of what went wrong are obscure. There are references to a convoluted business venture with another oil company. The deal was orchestrated by New York financier Mrs. Ada M. Barr after Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining had failed in January 1921.The next month, after being put in the hands of a receiver, the company’s assets were sold for $87,400.

The buyer was Mrs. Barr, who soon would be enveloped in controversy and litigation of her own.

Acorn Petroleum Corporation, represented by Mrs. Barr, offered bonds in the amount of $150,000 of Acorn Petroleum Corporation on the basis of $250 in bonds for each $1,000 of Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining stock held.

“The new company is operating the properties and has twenty-three producing wells, giving about ninety barrels of oil a day. The present low price for oil does not enable the company to earn sufficient income to pay interest on its bonds,” United States Investor noted. “Mrs. A.M. Barr, who arranged the financing of the new company, says that as soon as oil advances to a price that will permit, accrued interest on the bonds and dividends on the stock will be paid.”

But they weren’t.

By March 1923, investor Lewis H. Corbit filed a petition on behalf of a large number of local purchasers of stocks in the Acorn Petroleum Corporation of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The petition in the United States District court sought to determine the value of the local holdings, which represent an investment of approximately $100,000.

According to records, “In his complaint, asking for an investigation, Corbit alleges a stock, fraud in which $ 500,000 is involved. Certificates of shares held here were sold by a Mrs. A. M. Barr, it is disclosed in the petition.”

Further financial records and other details about Oklahoma-Texas Producing & Refining Company, Acorn Petroleum Corporation, and Mrs. Ada M. Barr can be research through the Library of Congress’ online Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

___________________

The stories of exploration and production (E&P) companies joining U.S. petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an annual AOGHS supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

.

(2007); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.