Protected: Oil & Gas History News, January 2022

Password Protected

To view this protected post, enter the password below:

To view this protected post, enter the password below:

Alas, there is very little chance your newly found old oil stock certificate will lead to petroleum riches here at Old Oil Stocks in progress G. Few come close to Not a Millionaire from Old Oil Stock about a certificate that spawned lengthy litigation with the Coca-Cola Company.

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society, which depends on your support, does not have resources for extensive research. As AOGHS looks into forum queries as part of its energy education mission, investigations have revealed interesting stories like Mrs. Dysart’s Uraniu Well and Buffalo Bill’s Shoshone Oil Company; others have found questionable dealings during booms and “black gold” fever epidemics like Arctic Explorer turns Oil Promoter.

Visit the Stock Certificate Q & A Forum for updates frequently added to the A-to-Z listing in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? AOGHS will continue to look into forum queries, including these “in progress.”

Garfield Oil & Refining Company

The Oklahoma business records department can provide incorporation information on the Garfield Oil & Refining Company, which had properties near Nowata but does not appear to have prospered.

Gate City-Wyoming Oil & Gas Company

The Gate City-Wyoming Oil and Gas Company incorporated in Idaho July 10, 1917, with Pocatello, Idaho, physician Dr. O.B. Steeley as president. The company acquired leases in Wyoming’s Lost Soldier Dome (640 acres); Rattlesnake Dome (640 acres); Laramie Dome (160 acres); and Rock Springs Dome (640 acres). Curiously, the company’s officers and property were also recorded as the Gate City Oil & Gas Company. Dr. Steeley died suddenly in June 1920. The Idaho secretary of state may have further information, but the company’s last filing was in September 1923. Its charter was forfeited on December 1, 1924. Read about other Wyoming wildcatters in First Wyoming Oil Wells and Buffalo Bill’s Shone Oil Company.

Gatex Oil Company

Gatex Oil Company incorporated in Delaware March 1, 1920. The company undertook exploratory “wildcat” drilling in northeast Texas’ Hopkins and Bowie counties with plans to drill in Hunt County. But in Hopkins County, its Davis No. 1 well was abandoned after reaching 2,020 feet deep without finding oil. Similarly in Bowie County, its Perkins No. 1 well was shut down at 1,570 feet deep with no success. Wildcat drilling on unproven land has always been risky; early failures have often exhausted under-capitalized ventures. This seems to have been the case with Gatex Oil Company, which was dissolved on June 4, 1936. (more…)

While resisting federal intervention in the marketplace, Kansas and other states in 1911 began legislating “Blue Sky” laws to protect investors from predatory and fraudulent stock sales schemes. But the problem continued to grow, especially in a post-World War I economic boom.

About 20 million people set out to make their fortunes in the stock market during the 1920s, according to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). These investors, both large and small shareholders, were “tempted by promises of ‘rags to riches’ transformations and easy credit, most investors gave little thought to the systemic risk that arose from widespread abuse of margin financing and unreliable information about the securities in which they were investing.”

Of the $50 billion in new securities offered in the 1920s, about half evenually became worthless, notes the SEC, which was established in 1934. The federal commisssion’s enforcement soon deterred many – but not all – scurrilous efforts to fleece unwary investors.

The often outrageous claims made by earlier oil stock promoters such as Seymour “Alphabet Cox” and former Arctic explorer Frederick Cook were constrained after establishment of the SEC and incarceration of offenders. “Caveat Emptor” nonetheless remained a primary mandate in the stock speculation as it did in decades past.

Homestead Oil Company of Dallas, Texas, ran afoul of the SEC in 1983. The company was charged with violating “the registration and antifraud provisions of the securities laws in the offer and sale of approximately $1.2 million of investment contracts in five oil and gas drilling programs to at least 125 investors.”

The Internal Revenue Service also pursued Homestead Oil for unpaid taxes amounting to “$247,532.37, plus statutory additions as allowed by law.” The company declared bankruptcy.

Litigation followed as Homestead Oil’s president sought to appeal his conviction “for common law fraud and for violations of the federal and state securities laws, (and) the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. (RICO)”

But on appeal, the court noted, “Homestead had offered to investors interests in oil and gas properties in eastern Oklahoma without proper SEC registration. They had failed to disclose investment information to Homestead’s investors and had made misrepresentations.”

Surviving stock certificates from Homestead Oil Company leave only scripophily value and a cautionary tale for investors to contemplate.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Home Oil & Development Company left better tracks in legal documents than in the oil patch.

“For quickness of action in the formation of an oil company and the sale of stock the Home Oil and Development Company holds the record,” declared the The Lafayette Gazette on October 5, 1901. “This company was organized last Friday morning and by Saturday evening, the ground had been secured for drilling and a man sent to purchase the necessary machinery for drilling. Monday morning they were authorized to sell seventy thousand shares at 33 and 1/3 cents per share. This morning all the stock is sold. They will begin work next week.”

Despite being at the heart of Louisiana’s first oil boom, which between 1902 and 1908 produced virtually all of of the state’s oil, the company failed. Louisiana court records reveal Home Oil & Development ‘s demise in cases (no. 4374, no. 5021, no. 4733), and finally in the Louisiana Supreme Court (no. 15,468). A Louisiana company born to exploit the newly discovered Jennings oilfield, Home Oil & Development was insolvent within five years of its creation. Irate stockholders brought suit to recover some part of their lost investments.

“Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901 – 1946” by Kenny Arthur Franks and Paul F. Lambert includes images of Home Oil & Development Company.

Among the complainants were the Heywood brothers, whose discovery of the first Louisiana oil well in September 1901 had spawned a boom in drilling – and speculation.

By 1902, Home Oil & Development litigation in the Louisiana Supreme Court revealed that at the time of the bankruptcy, “The only asset owned the corporation consists of the amounts owing to it by its stockholders on the unpaid portion of the purchase price of the stock held and owned by them.”

With this rationale, those stockholders whose subscriptions were fully paid, “seek to obtain a personal judgement for the amount…against some few of its individual stockholders, claiming that they have not paid to it the full amount of their subscription to stock.”

The court did not agree, noting “the proper result should not be for individual creditors to institute individual actions inuring to their separate benefit and advantage.” The court concluded that the affairs of the corporation “should be placed in liquidation in the hands of some officer or officers acting in the interest of and for the benefit of all parties concerned.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________

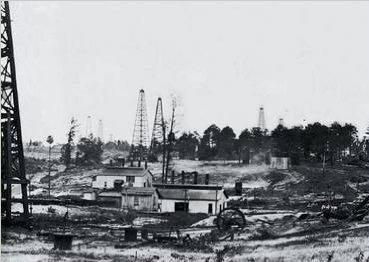

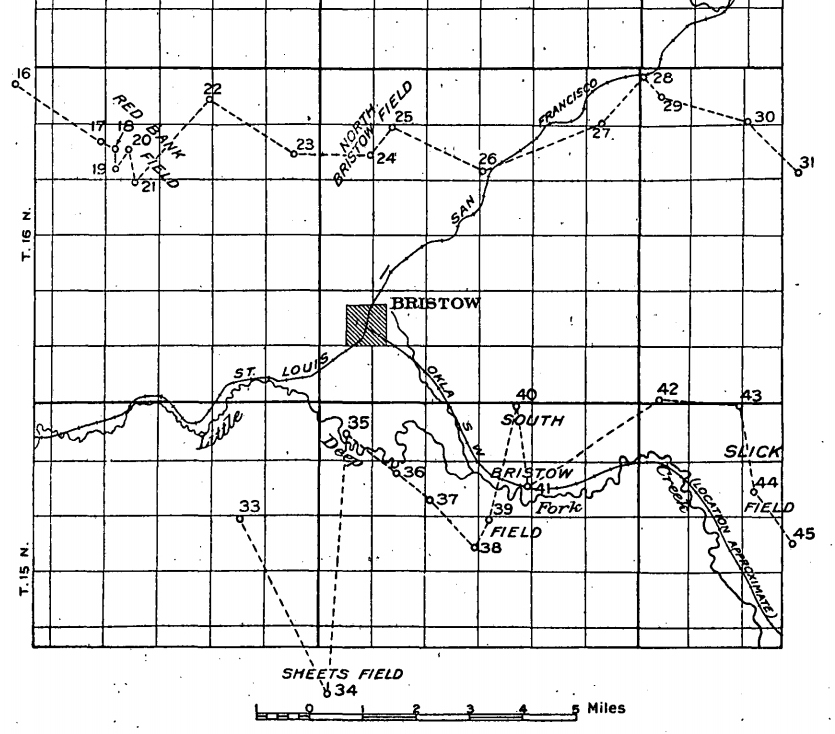

The land around Bristow, Oklahoma, was once dismissed as “condemned territory” and deemed unproductive by geologists. Thirty-five dry holes had substantiated their judgement, despite the location between two of Oklahoma’s most productive oilfields, Cushing-Drumright and Glenn Pool.

The Cushing-Drumright field, about 30 miles northwest of Bristow, was discovered by Oklahoma’s “King of the Wildcatters,” Tom Slick, in 1912. Once known as “Dry Hole Slick,” his Wheeler No. 1 well revealed an oilfield that produced a lot of oil for the next 35 years, reaching 330,000 barrels of oil every day at its peak. With its pipelines and vast storage facilities, Cushing today is the trading hub for oil in North America.

Thirty miles east of Bristow, the Glenn Pool field was discovered on the Creek Indian Reservation south of Tulsa in 1905 – two years before Oklahoma statehood. Combined with the earlier “Red Fork Gusher,” Glenn Pool would help make Tulsa the “Oil Capital of the World.”

Despite the Bristow area’s dry holes between the giant oilfields, Continental Petroleum Company attempted an exploratory well just east of the town. On October 17, 1921, its Ben Sharper No. 1 well was completed with oil production of 1,000 barrels a day. It was the discovery well for what became known as the Continental Pool. The success soon drew many competitors and Bristow’s population soared.

Despite the Bristow area’s dry holes between the giant oilfields, Continental Petroleum Company attempted an exploratory well just east of the town. On October 17, 1921, its Ben Sharper No. 1 well was completed with oil production of 1,000 barrels a day. It was the discovery well for what became known as the Continental Pool. The success soon drew many competitors and Bristow’s population soared.

Continental Petroleum had been formed as a Delaware corporation in January 1919, with former Colorado banker A.A. Rollestone as president. Rollestone had also purchased and was president of Continental Refining Company, which operated a 2,500 barrel-a-day refinery in Bristow, where both companies were located.

One Rollestone company was in the oil exploration business and the other was refining crude oil piped in from the Cushing-Drumright field. Moody’s Analyses of Investments reported Continental Petroleum had about 6,000 acres under lease in Oklahoma and another 3,000 acres in Texas.

Continental Petroleum’s success with the Continental Pool brought suitors. In January 1922, stockholders approved purchase of the company by Michael L. Benedum’s Transcontinental Oil Company.

Benedum, a successful independent oilman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1924 formed the Big Lake Oil Company, which built the first oil company town in the Permian Basin in West Texas. A 1923 wildcat well there, the Santa Rita No. 1, had uncovered the 300-mile basin. He would also be known as “King of the Wildcatters.”

The Transcontinental Oil buyout of Continental Petroleum made A.A. Rollestone a wealthy man, according to the trade publication the Petroleum Age, which said the deal gave him an address “on a prominent Easy Street corner.”

In 1936, the Ohio Oil Company (later Marathon), acquired Transcontinental Oil Company. Although Continental Petroleum stock certificates, redeemed and canceled long ago, have no value as negotiable securities, the company’s Oklahoma oil patch history may help make them collectable.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support this AOGHS.ORG energy education website. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2018 Bruce A. Wells.

___________________________________________________________________________________